Review: Radioactive — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Radioactive

⭐⭐⭐⭐

Rating: PG-13

Run Time: 1 hour 49 minutes

Stars: Rosamund Pike, Sam Riley, Yvette Feuer, Aneurin Barnard

Writer: Jack Thorne

Director: Marjane Satrapi

Streaming on Amazon Prime

Tackling the life story of pioneering nuclear scientist Marie Curie, Rosamund Pike continues her recent explorations of tough-to-pin-down historic women — pithy females who tossed aside their cultures’ expectations and plunged stubbornly forward, either failing to hear the cries of objection or simply choosing to ignore them.

In A United Kingdom she played Ruth Williams, a London woman who defied the social norms of two countries when she married an African king in the late 1940s. She chain-smoked and growled her way through A Private War, painting an uncompromisingly coarse portrait of war correspondent Marie Colvin. And here in Radioactive, playing the Mother of the Atomic Age, Pike strikes yet another defiant pose as a woman who, despite her obvious brilliance, battles at every turn to make her mark in the male-dominated scientific world of the early 20th century.

It’s a startling performance that commands virtually every moment of the film’s run time, as Pike’s Curie runs into one institutional blockade after another.

Unmarried and fighting to keep her position at a Paris laboratory, in one early scene Curie storms into an all-male (of course) board meeting to demand more lab space — and ends up fired. Facing professional ruin, Pike’s face swims with conflicting emotions: fury, surprise, hurt, and dread fear. But even as her expressions flit from one state of mind to another, she seems to grow in stature to the point where the guys with the cigars — and we — begin to wonder if she’s going to leap at them from across the conference table.

So prickly is Pike’s Curie that we almost gasp in astonishment when she lowers her stoic resolve long enough — but just barely so — to fall in love with and marry Pierre Curie, an uncommonly open-minded fellow scientist (Sam Reilly, channeling the same suave charm that made him the perfect alt-world Mr. Darcy in 2016’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies).

Iranian director Marjane Satrapi — Oscar-nominated for her animated film Persepolis — knows she’s got a good thing going in Pike. When’s she’s not simply turning the whole film over to her star she’s taking devilish delight in depicting the world’s turn-of-the-century radiation mania — depicting with dark glee such products as radioactive toothpaste and chewing gum. Of course, the fun is all over when Marie, Pierre, and their fellow scientists start coughing up blood, signaling the awful realities of unchecked radiation.

Screenwriter Jack Thorne (Wonder, The Aeronauts) makes the risky choice of repeatedly flash forwarding to the decades following Curie’s death, reminding us of the world her discoveries created, from the atomic bomb to radiation therapy to Chernobyl. Indeed, at times he literally injects Madame Curie herself into these scenes, a ghostly witness to her complicated legacy. It doesn’t always work — Curie’s life is compelling enough without resorting to a tricked-up narrative — but the ploy does serve to remind us that although the events here unfolded more than a century ago, some of the modern world’s most profound dilemmas harken back to that dusty, irradiated laboratory in pre-World War I Paris.

In any case, all is forgiven whenever Pike is on the screen. History is always more fun when filmmakers leave the rough edges intact, and Radioactive does just that — thanks mainly to the superb work of an actor who thrives on showing those edges in stark, supremely human, relief.

Featured image: Rosamund Pike in Radioactive (Photo Credit: Laurie Sparham; StudioCanal/Amazon Studios)

100 Years Ago: The Women Who Ran Off with the Circus

In a time before television or Twitter, the traveling circus was a dominant, all-American form of entertainment. The young and old, rich and poor alike would gather to witness the exotic animals and superhuman acrobatics under the big top each summer. Traveling circuses would shut down entire towns with their parades and engulf the country in “sawdust and spangles.”

The larger-than-life showmen behind the country’s great circuses, like P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, and the Ringling Brothers, are still household names, but many of the performers, daredevils, and animal trainers who astounded their audiences and made weekly headlines have been forgotten.

Part of the appeal of circus folk lay in the mystery surrounding them. Who were they and where did they come from, these people who descended on the most provincial towns with strange talents and glamorous costumes? At the turn of the century, the circus spotlight began to shine on women, highlighting their athletic talents juxtaposed with dainty beauty.

Historian Janet M. Davis writes in The Circus Age that “In an era when a majority of women’s roles were still circumscribed by Victorian ideals of domesticity and feminine propriety, circus women’s performances celebrated female power, thereby representing a startling alternative to contemporary social norms.”

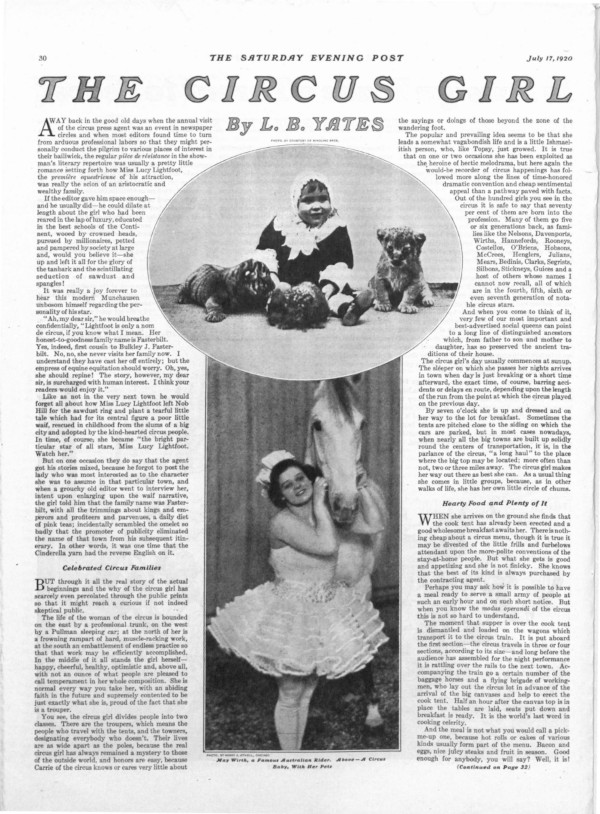

According to “The Circus Girl,” an article by L.B. Yates that appeared in the Post 100 years ago, the intrigue of the female circus performer was heightened by press agents who sowed fictional accounts to local papers of either some rich society girl or poor waif who had found a calling as a trick horse rider in the circus. It was usually a fabrication, as Yates claimed, since the vast majority of circus performers were born into the profession.

But the treatment of this new crop of female performers, in the press and in the culture, was a tightrope act of sorts. The circus offered a home for some outsiders and castaways and provided independence and adventure for its female stars. For audiences, it afforded titillating, exotic glimpses of the limits of the human body while promising to uphold decency in its ranks.

The women of the American circus during its golden age worked tirelessly to perfect their acts, stealing shows and breaking stunt records at a unique time in history that straddled the old conventions with the new promise of suffrage and feminism.

Lillian Leitzel

“I resent having people come to my tent, stare at me as though I were a freak and then turn away laughing, as if they’d seen some wild animal,” the famous aerialist Lillian Leitzel told the Post in 1920. “They seem to assume that circus people have not got beyond the primitive stage of the cave man and are an aggregation of unlettered louts wholly devoid of the commonest sense of social amenities.”

Leitzel was indeed rich in social amenities, and she was also just plain rich. According to historian Janet M. Davis, the performer was making up to $200 a week in 1917 with Ringling Brothers (worth more than $4,000 in 2020), and it wasn’t uncommon for female circus stars to rake in more than their male counterparts. She had her own train car that contained a piano, and at each stop she would dress in her own private tent. By the 1920s, she was pulling in $500 per week, according to John Culhane in The American Circus.

Known as a brassy primadonna, Leitzel grew up in a Czech circus family and began in the gymnasium at 3 years old. Her signature act was to bound up the rope and hold her hand in a loop while throwing her body up and around, dislocating her shoulder over and over again as she performed her “one-arm planges.” As a percussionist carried on a drumroll, the audience would count her swingovers, one time as many as 249.

“Accidents? Oh, well, they’re liable to happen any time,” Leitzel told the Post. “But I never think of that. Whenever a performer gets to studying about the chances he or she is bound to take, he has outlived his usefulness. An acrobat must have hundred per cent nerves.”

She entertained other elite performers, senators, businessmen, and especially children in her private car. She was known for giving parties for all of the circus children and lavishing gifts and sweets on them, possibly because she was stripped of a childhood herself, according to Culhane.

Leitzel encouraged women to exercise to stay healthy, in spite of lingering Victorian notions that athleticism made women ugly and manlike. “Down with the corset,” she told newspapers in 1923. “Put a brick in the atrocious garment and hurl it into the Niagara River.” She encouraged women to take up swimming or some other sport they enjoyed, promising “you can eat what you want and work off the energy in exercise.”

Leitzel married the Mexican trapeze artist Alfredo Codona, and their passionate celebrity marriage was rife with jealousy and resentment. When Leitzel traveled to Europe in 1931, Codona went separately with an equestrian with whom he was having an affair. In Cophenhagen, Leitzel was performing her one-arm planges when the brass ring she was holding snapped, and she fell 20 feet onto her head. Although she insisted on continuing her act, her handlers sent her to the hospital. She died the next morning from a concussion.

Mabel Stark

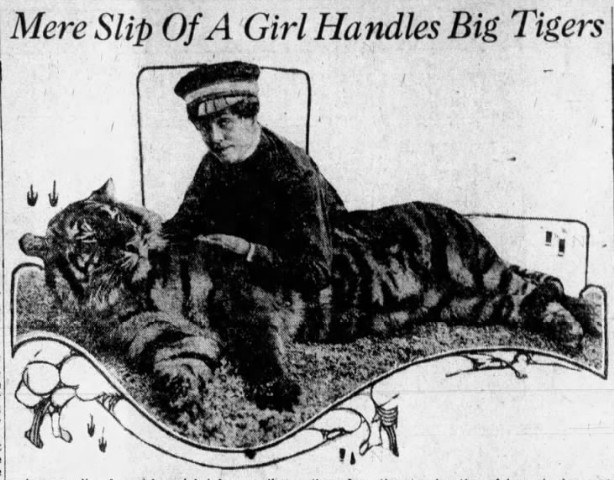

Mabel Stark was working as a nurse — with a stint as a burlesque dancer — when she found a calling to work with big cats in Venice, California around 1911. She stumbled onto the grounds of the traveling Al G. Barnes Circus and became obsessed with Bengal tigers. Stark joined the show, and within a few years she was a big cat trainer. Stark was the first American woman to take up the dangerous profession, let alone to achieve such renown.

Over the years, she became one of the most famous tiger (and lion and panther) tamers in the world, joining the Ringling Brothers in 1920. Newspapers gushed over her unique wrestling act. Stark would roll around with any of her 18 tigers, giving the impression of a perilous struggle.

Although Stark spent most of her time with her cats and treasured them dearly, she never lost sight of the risk of working with tigers. She gave some insight to a Public Ledger reporter in 1923: “The tone of the voice, the determination of it, has a great deal to do with subduing wild animals. Don’t let uncertainty or fear creep into your tones, or you’re gone. A great life, so to speak, if you don’t weaken.”

As with many who work with predator animals, Stark sustained serious injuries throughout her career (according to a profile in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1950). In Maine, she was mauled in the ring and required 378 stitches. In Arizona, she was bitten by a tiger named Nellie and finished her act with a limp left arm. In spite of it all, she continued to defend her fierce friends and the connection she had with them.

Stark’s story ultimately ended in tragedy. After retiring from the circus in the late 1930s, she settled in at an amusement park called Jungleland. Stark was let go for insurance reasons, and then one of her tigers escaped and was shot. The devastated near-80-year-old took her own life.

May Wirth

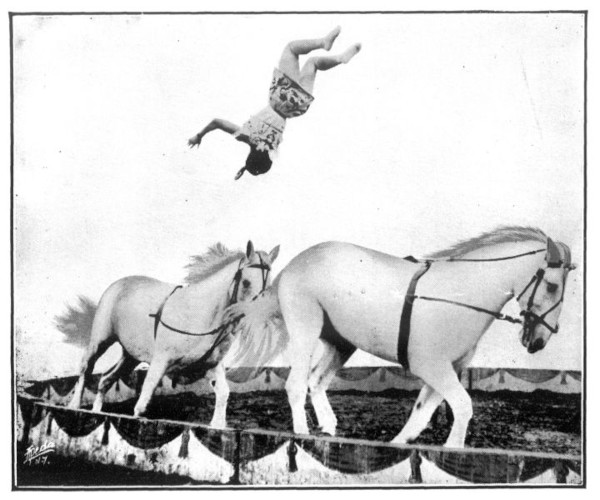

Billed as “The World’s Greatest Rider,” May Wirth was only 17 when she made her first appearance in the Ringling Brothers’ show at Madison Square Garden. The Australian transplant wore a giant hair bow and leapt from horse to horse, completing flips and twists that dazzled audiences and — sometimes moreso — other riders.

Wirth was an orphan who performed as a five-year-old contortionist and was eventually adopted by the down-under circus rider Marilyas Wirth Martin. According to the Braathens, two Madison, Wisconsin circus buffs writing in The Capital Times in 1973, Will Rogers witnessed young Wirth riding in her home country and predicted “the day would come when there would be but two types of bareback riders in the world, May Wirth and all the others.”

When the Braathens asked about her legendary forward somersault, Wirth recalled that Mr. Ringling was skeptical that anyone could complete such a trick, and when she tried it for him: “I missed it and fell on my back right in front of Mr. John. I got up like a streak of lightning, ran and vaulted onto the horse again and did the stunt over for him, this perfectly, and did the somersault feet to feet. That earned me my first season’s contract with John Ringling.”

The sweetheart of the circus made the front page of The New York Times after an unfortunate slip in 1913 caused her to be dragged around the track behind her horse by her feet. Nine years later, the paper reported that she had accepted the challenge of riding a bull, and better yet: “Miss Wirth not only rode the bull, reputed to be a most ferocious beast, 3 years old and weighing 2,400 pounds, but she rode him standing on her hands upon his back.”

Wirth retired from the big top in 1937 and went to live with her mother in New York. She later moved to Sarasota, where the Ringling Museum and Circus Hall of Fame was located. She was inducted in 1964.

Featured image: 1890-1900, Calvert Litho. Co., Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The Circus Age by Janet M. Davis

The American Circus by John Culhane

Women of the American Circus, 1880-1940 by Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene

Considering History: Sophia Hayden and the Hidden Cost of American Sexism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Late last week, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren ended her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, leaving the primary without any of the ground-breakingly high number of women who had once been part of its slate of candidates. (Hawaii Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard remains in the race but has received only two delegates and has never polled above low single digits.) While Warren’s campaign and exit were both influenced by a number of factors, her departure has occasioned numerous commentaries on the continued, frustrating reality (particularly when compared to most other nations in the world) that the United States has never elected a woman to its highest political office — a reality particularly worth engaging on the occasion of Women’s History Month.

The presidency is a strikingly visible element of American society, making the historic and continued absence of women likewise quite apparent. But that absence also reflects a far wider and deeper, and yet often more difficult to spot, aspect of our collective histories: the ways in which sexism and the glass ceiling have driven so many of our most talented and impressive women out of their chosen professions, leaving our entire society profoundly diminished as a result. Few American figures and stories encapsulate that hidden cost of sexism better than the architect Sophia Hayden Bennett (1868-1953).

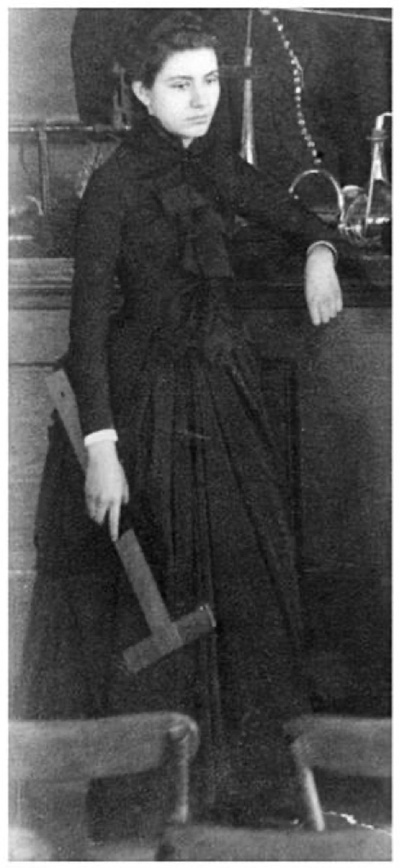

Hayden was born in Santiago, Chile, to a Chilean mother (Elezena Fernandez) and an American father (George Hayden), a dentist who had moved to Chile from his native Boston a few years earlier. When she was six, her parents sent her back to the Boston area by herself, to live with her grandparents in Jamaica Plain and attend school. While studying at West Roxbury High School she became interested in architecture, and she would go on to attend MIT, graduating in 1890 as one of the first two female graduates of a collegiate architecture program in American history (her classmate, Lois Lilley Howe, with whom Hayden shared a drafting room at MIT, was the second).

Despite that prestigious degree, Hayden was unable to find an apprentice position at any local architecture firms and took a job teaching mechanical drawing at the Eliot School, a vocational grammar school in Boston. But less than a year later she learned of a strikingly unique new opportunity: the chance to design the Woman’s Building, one of the planned exhibition halls for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. After extensive negotiation, women’s rights groups had convinced the exposition directors to create a Board of Lady Managers comprised entirely of women, and in February 1891 that board, headed by the socialite and activist Bertha Honoré Palmer, announced a competition for the Woman’s Building design, open only to female architects.

The competition’s $1000 prize/commission was significantly less than what was offered to male architects for the exposition’s other buildings, and so Louise Blanchard Bethune, considered the first professional female architect in America, refused to submit a concept. But Hayden did submit, and out of the 13 proposed designs it was her innovative concept, based in part on concepts from Italian Renaissance classicism, that the Board (along with Chief of Construction Daniel Burnham) selected as the winner. She traveled to Chicago to begin work on turning that design into construction plans as quickly as possible, as construction needed to begin in the summer of 1891 to be ready for the exposition’s May 1893 opening.

That hugely expedited timeline was only one of many challenges that Hayden would face over the next two years. Despite having chosen Hayden’s design, the Board of Lady Managers identified a number of perceived shortcomings and requested many changes, including the addition of an entirely new third story, which required Hayden to overhaul many other aspects as well. Moreover, Board Chair Palmer decided to take control of the building’s interior design away from Hayden entirely after the architect resisted some of the Board’s other substantial proposed changes. Hayden managed to respond to, complete, and work around such extraordinary requests within that very tight schedule and on budget to boot, and the Women’s Building was formally introduced at the exposition’s October 21, 1892, dedication ceremony. But shortly after, it was reported that Hayden suffered a possible nervous breakdown (in some reports referred to as “melancholia”) in Burnham’s office, and she was confined to a “rest home” for months in order to recover.

It’s impossible to know precisely the role that Hayden’s gender played in all those developments, although it’s certainly important to note that such medical diagnoses and conditions themselves were hugely gendered in the late 19th century (as illustrated by the long history of the illness known as “hysteria,” as well as related contexts like physician S. Weir Mitchell’s popular “rest cure” for women and the depiction of its destructive effects in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s autobiographical short story “The Yellow Wallpaper”). Moreover, many of the prominent responses to her design were overtly limited by narratives of gender, as illustrated by architect and critic Henry van Brunt’s argument (as part of a long series entitled “Architecture at the World’s Columbian Exposition”) that the building seemed “rather lyric than epic in character, and [that] it takes its proper place on the Exposition grounds with a certain modest grace of manner not inappropriate to its uses and to its authorship.”

Although Hayden was “cured” in time to leave the rest home and attend the exposition before its November 1893 closing (after which the Women’s Building, like most of the exposition’s structures, was demolished), she would as far as we know never design another building. An editorial in the journal American Architect lamented that fate while managing to reinforce sexist narratives at the same time, writing, “Miss Hayden has been victimized by her fellow-women. The unkind strain would have been the same had the work been as unwisely imposed upon a masculine beginner.” Hayden returned to the Boston area, eventually marrying local painter William Bennett in May 1900. Their wedding announcement in the Boston Daily Advertiser noted that “both are highly esteemed and respected . . . versatile as well as talented,” but again as far as we know Hayden never again publicly employed her prodigious talents, living her remaining six decades as a private person in their Winthrop, MA home.

What might American architecture, America’s cities, American society have looked like if Sophia Hayden had continued to design buildings? What would American history look like if we had elected a woman president by now (or if women had received the vote before 1920, for another example)? Such questions remain painfully hypothetical and unknowable, reflecting a collective loss that parallels the individual and personal costs of sexism so embodied by a figure like Sophia Hayden.

Featured image: The 24 female MIT students in 1888. Sophia Hayden is in the front row, far left. (MIT Museum)

How Our Grandmothers Disappeared into History

I recently googled my grandmother’s name. I wanted to know the date she died so I could better place a childhood memory. In the 21st century, embarrassingly, the internet has become the family Bible. The first hit was a link to my own book, a history of Southern motherhood. I had dedicated the book, in part, to her. My stomach gave a funny flip. I had gone looking for my grandmother and found myself — and yet my own writing was resurrecting her. This is an ouroboros of women’s history. We search for our mothers in the past and find only mirrors.

Women are notoriously hard to find in American archives. Their names keep getting folded under. You have to trace fathers and husbands to triangulate an identity. Names float down the generations on rafts of privilege: whiteness helps, as does wealth, and maleness makes everything simpler. A George Washington is a George Washington eternal. (His wife Martha was a Dandridge, then a Custis, then a Washington.) I am white, and my mother’s ancestors were of the class that kept others in bondage. Even with all their record-keeping, I can see only eight generations down the female line: Elise, Elise, Elise, Ellen, Elizabeth, Elizabeth, Mary, Ann, and then a woman identified as “Unknown.” Unknown couldn’t legally own property and had nothing to pass down except the intangibles of her voice, her scent, whatever knowledge she possessed, and, perhaps, her first name. Maybe she was named Ann too.

Names float down the generations on rafts of privilege: whiteness helps, as does wealth, and maleness makes everything simpler.

Though trained as a historian, I am now a novelist, a sequence of careers that anyone who knew me years ago could have predicted. The fictions I wrote as a youth were nearly suffocated with names. I was a budding genealogist, a self-historian, and was entranced by naming — that defining impulse that led me also to fill my mother’s grade books with made-up students. But naming is nurturing too; I wanted to rope my characters into a web of relation. When I was 12 or 13, I learned about Lydia, an ancestor on a different branch of the family who would have been about my age during the Revolutionary War. The story I started writing about her got sidetracked by a detailed map I made of her 45 cousins, but what narrative I spun was marked by my obsessions:

Father used to call me Lyd-John. It was a little joke of ours — I was the boy born with a silly girl’s name. I never used to consider myself bound by all the rules of maidenhood; the etiquette, the dress, the eating habits (Father says I eat like a horse), but as I grow up and across and sideways, I find myself uncomfortably slipping into propriety. I fear I’ve been around Mother too much.

Perhaps my fear was invisibility: not being remarked, recorded, remembered. Another of my early American grandmothers was named Desire — who could forget that? One of her grandmothers shows up on our family tree as Wife #1. Beyond that, unknowns.

As women took the names of their men, so too were many enslaved people stuck with the names of those who claimed to own them. In writing my history book, I learned of a Southern family that had maintained better records than my own. Each newborn was listed with a name, birth date, and the name of the child’s mother. No fathers at all, because the state of enslavement, since the Virginia Slave Law of 1662, was dependent on the condition of the mother. White men could gift their names to white descendants, erasing the heritable influence of white women, and simultaneously — conveniently — absent themselves from black lineages, converting their own forced offspring into property.

As the names of black babies in that Southern family were being recorded by a white hand, a white daughter (Sarah) was taken from home by her husband. Her letters to her mother (also Sarah) are one-note: “I cant help regretting that I could not spend a few more days with my ever Dear Mother before I left you Dearst and best of Mothers. Of all the tryalls that ever Crossed me that of parting from my Dear mother has been the hardest.” When the elder Sarah died in 1818, the 37 enslaved people she counted as her personal property were sold, at least five of them mothers with young children. Thirty-seven bodies amounted to $18,535 (about $350,000 today), money which went — where? To Sarah’s one surviving son, most likely: Francis, named after his father.

But white Sarah had named her daughter Sarah, who named her daughter Sarah. And on the plantation simultaneously was a black Sarah, whose daughter Moll named her first daughter Sarah. My white great-grandmother Elise named her daughter Elise, who named her daughter Elise. There is a holding onto identity — to slim power — here.

Stories can live on without names, though they’re harder to find, harder to push to the front of others’ imaginations.

How do you search for a woman in the archives if her name is only Sarah? For many African Americans — whose racial identity was determined by legal status, whose legal status derived from the mother — genealogies break off mid-tree. Even in white lineages, women dangle tenuously, like leaves. How to find a simple “Sarah” in America? Sarah who raised you, who washed you, who maybe taught you letters, and how to hide, and what parts of religion to trust? To hunt for our mothers’ names in the past is to pull back the heavy curtains of property — both being propertied and being property. Names denote possession. I’m a descendant of the South Carolina Clinkscales. So too is Jimmy Carter; so too is a black woman who checked me in at a conference several years ago. I recently saw a Clinkscales pop up in the credits of I, Tonya, and I later looked him up: a young black man from Georgia. We might be kin; we might just share a white man’s name.

Naming alone doesn’t create history, as I learned in my early attempts at historical fiction. Stories can live on without names, though they’re harder to find, harder to push to the front of others’ imaginations. So I call out the dead Sarahs when I find them, I ask the living Elises for their memories. I clutch my ancestors’ objects, which I know I’m lucky to claim. I have my great-great-great-grandmother’s fork, my great-great-grandmother’s ring, my great-grandmother’s sewing table, my grandmother’s small pink compact, the powder within still smelling strongly of her. A fork, a ring, a table, a mirror. This is the moral of naming, that what has a label is remembered. If we in turn label the unknowns, will the ghosts of our mothers begin to rise?

This article originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).

It is also featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock