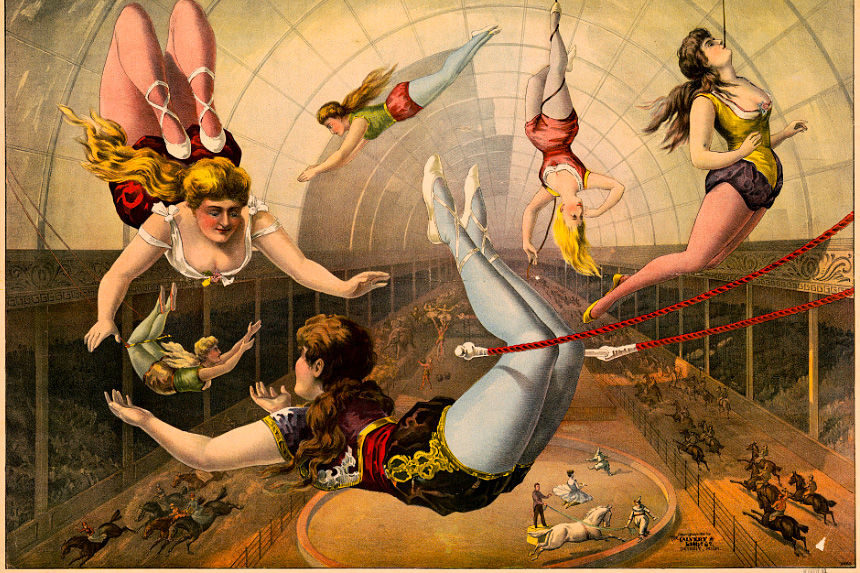

In a time before television or Twitter, the traveling circus was a dominant, all-American form of entertainment. The young and old, rich and poor alike would gather to witness the exotic animals and superhuman acrobatics under the big top each summer. Traveling circuses would shut down entire towns with their parades and engulf the country in “sawdust and spangles.”

The larger-than-life showmen behind the country’s great circuses, like P.T. Barnum, James Bailey, and the Ringling Brothers, are still household names, but many of the performers, daredevils, and animal trainers who astounded their audiences and made weekly headlines have been forgotten.

Part of the appeal of circus folk lay in the mystery surrounding them. Who were they and where did they come from, these people who descended on the most provincial towns with strange talents and glamorous costumes? At the turn of the century, the circus spotlight began to shine on women, highlighting their athletic talents juxtaposed with dainty beauty.

Historian Janet M. Davis writes in The Circus Age that “In an era when a majority of women’s roles were still circumscribed by Victorian ideals of domesticity and feminine propriety, circus women’s performances celebrated female power, thereby representing a startling alternative to contemporary social norms.”

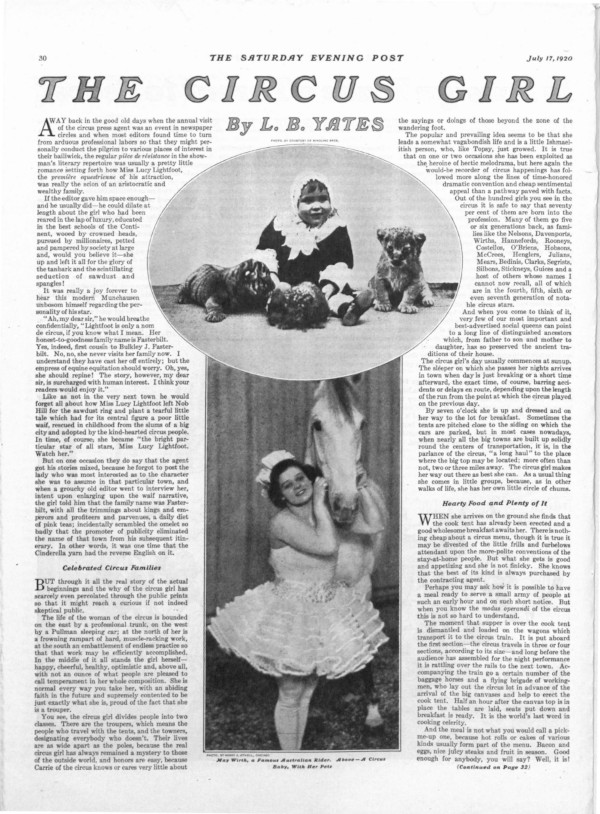

According to “The Circus Girl,” an article by L.B. Yates that appeared in the Post 100 years ago, the intrigue of the female circus performer was heightened by press agents who sowed fictional accounts to local papers of either some rich society girl or poor waif who had found a calling as a trick horse rider in the circus. It was usually a fabrication, as Yates claimed, since the vast majority of circus performers were born into the profession.

But the treatment of this new crop of female performers, in the press and in the culture, was a tightrope act of sorts. The circus offered a home for some outsiders and castaways and provided independence and adventure for its female stars. For audiences, it afforded titillating, exotic glimpses of the limits of the human body while promising to uphold decency in its ranks.

The women of the American circus during its golden age worked tirelessly to perfect their acts, stealing shows and breaking stunt records at a unique time in history that straddled the old conventions with the new promise of suffrage and feminism.

Lillian Leitzel

“I resent having people come to my tent, stare at me as though I were a freak and then turn away laughing, as if they’d seen some wild animal,” the famous aerialist Lillian Leitzel told the Post in 1920. “They seem to assume that circus people have not got beyond the primitive stage of the cave man and are an aggregation of unlettered louts wholly devoid of the commonest sense of social amenities.”

Leitzel was indeed rich in social amenities, and she was also just plain rich. According to historian Janet M. Davis, the performer was making up to $200 a week in 1917 with Ringling Brothers (worth more than $4,000 in 2020), and it wasn’t uncommon for female circus stars to rake in more than their male counterparts. She had her own train car that contained a piano, and at each stop she would dress in her own private tent. By the 1920s, she was pulling in $500 per week, according to John Culhane in The American Circus.

Known as a brassy primadonna, Leitzel grew up in a Czech circus family and began in the gymnasium at 3 years old. Her signature act was to bound up the rope and hold her hand in a loop while throwing her body up and around, dislocating her shoulder over and over again as she performed her “one-arm planges.” As a percussionist carried on a drumroll, the audience would count her swingovers, one time as many as 249.

“Accidents? Oh, well, they’re liable to happen any time,” Leitzel told the Post. “But I never think of that. Whenever a performer gets to studying about the chances he or she is bound to take, he has outlived his usefulness. An acrobat must have hundred per cent nerves.”

She entertained other elite performers, senators, businessmen, and especially children in her private car. She was known for giving parties for all of the circus children and lavishing gifts and sweets on them, possibly because she was stripped of a childhood herself, according to Culhane.

Leitzel encouraged women to exercise to stay healthy, in spite of lingering Victorian notions that athleticism made women ugly and manlike. “Down with the corset,” she told newspapers in 1923. “Put a brick in the atrocious garment and hurl it into the Niagara River.” She encouraged women to take up swimming or some other sport they enjoyed, promising “you can eat what you want and work off the energy in exercise.”

Leitzel married the Mexican trapeze artist Alfredo Codona, and their passionate celebrity marriage was rife with jealousy and resentment. When Leitzel traveled to Europe in 1931, Codona went separately with an equestrian with whom he was having an affair. In Cophenhagen, Leitzel was performing her one-arm planges when the brass ring she was holding snapped, and she fell 20 feet onto her head. Although she insisted on continuing her act, her handlers sent her to the hospital. She died the next morning from a concussion.

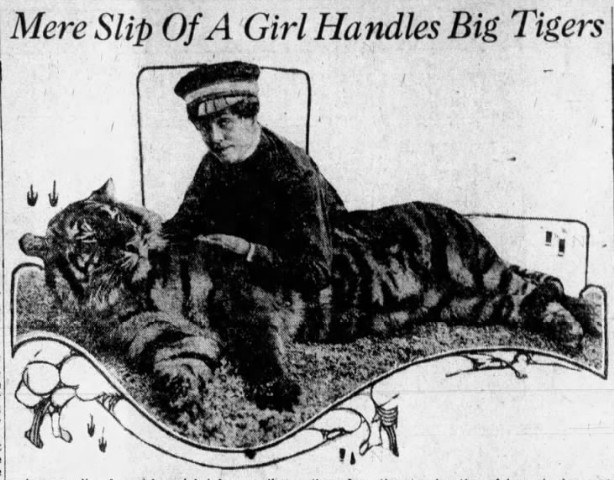

Mabel Stark

Mabel Stark was working as a nurse — with a stint as a burlesque dancer — when she found a calling to work with big cats in Venice, California around 1911. She stumbled onto the grounds of the traveling Al G. Barnes Circus and became obsessed with Bengal tigers. Stark joined the show, and within a few years she was a big cat trainer. Stark was the first American woman to take up the dangerous profession, let alone to achieve such renown.

Over the years, she became one of the most famous tiger (and lion and panther) tamers in the world, joining the Ringling Brothers in 1920. Newspapers gushed over her unique wrestling act. Stark would roll around with any of her 18 tigers, giving the impression of a perilous struggle.

Although Stark spent most of her time with her cats and treasured them dearly, she never lost sight of the risk of working with tigers. She gave some insight to a Public Ledger reporter in 1923: “The tone of the voice, the determination of it, has a great deal to do with subduing wild animals. Don’t let uncertainty or fear creep into your tones, or you’re gone. A great life, so to speak, if you don’t weaken.”

As with many who work with predator animals, Stark sustained serious injuries throughout her career (according to a profile in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1950). In Maine, she was mauled in the ring and required 378 stitches. In Arizona, she was bitten by a tiger named Nellie and finished her act with a limp left arm. In spite of it all, she continued to defend her fierce friends and the connection she had with them.

Stark’s story ultimately ended in tragedy. After retiring from the circus in the late 1930s, she settled in at an amusement park called Jungleland. Stark was let go for insurance reasons, and then one of her tigers escaped and was shot. The devastated near-80-year-old took her own life.

May Wirth

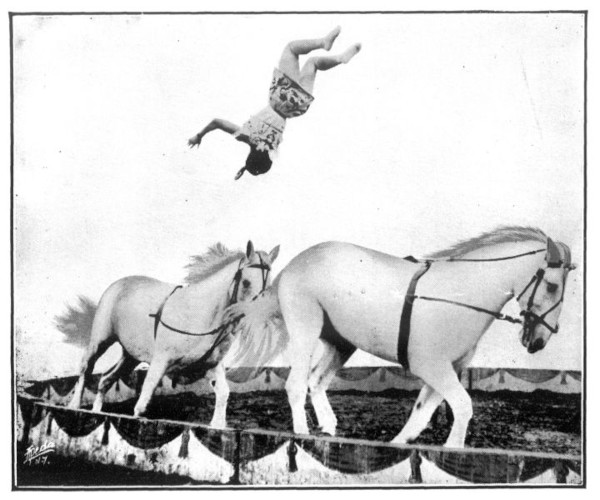

Billed as “The World’s Greatest Rider,” May Wirth was only 17 when she made her first appearance in the Ringling Brothers’ show at Madison Square Garden. The Australian transplant wore a giant hair bow and leapt from horse to horse, completing flips and twists that dazzled audiences and — sometimes moreso — other riders.

Wirth was an orphan who performed as a five-year-old contortionist and was eventually adopted by the down-under circus rider Marilyas Wirth Martin. According to the Braathens, two Madison, Wisconsin circus buffs writing in The Capital Times in 1973, Will Rogers witnessed young Wirth riding in her home country and predicted “the day would come when there would be but two types of bareback riders in the world, May Wirth and all the others.”

When the Braathens asked about her legendary forward somersault, Wirth recalled that Mr. Ringling was skeptical that anyone could complete such a trick, and when she tried it for him: “I missed it and fell on my back right in front of Mr. John. I got up like a streak of lightning, ran and vaulted onto the horse again and did the stunt over for him, this perfectly, and did the somersault feet to feet. That earned me my first season’s contract with John Ringling.”

The sweetheart of the circus made the front page of The New York Times after an unfortunate slip in 1913 caused her to be dragged around the track behind her horse by her feet. Nine years later, the paper reported that she had accepted the challenge of riding a bull, and better yet: “Miss Wirth not only rode the bull, reputed to be a most ferocious beast, 3 years old and weighing 2,400 pounds, but she rode him standing on her hands upon his back.”

Wirth retired from the big top in 1937 and went to live with her mother in New York. She later moved to Sarasota, where the Ringling Museum and Circus Hall of Fame was located. She was inducted in 1964.

Featured image: 1890-1900, Calvert Litho. Co., Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The Circus Age by Janet M. Davis

The American Circus by John Culhane

Women of the American Circus, 1880-1940 by Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

My God Nick, you REALLY outdid even yourself on THIS story. I can’t get over these women and what they accomplished, and their longevity in the business despite repeated injuries and risks. Lillian Leitzel was ahead of her time in many ways, including encouraging women’s exercise. She was a kind woman with a soft spot for children. I’m so sorry she died as a result of that fall.

The fact Mabel Stark started out as a nurse is certainly as surprise, if not shocking. I can see how she fell in love with the tigers, and the longer she worked with them without incident, the more she would feel a false sense of security. I can understand that. No matter how wonderful and loving they are, they ARE wild animals. Mauled, bitten, requiring 378 stitches. I’m very sorry her life ended the way it did, but can understand it.

What May Wirth did may have been the MOST outrageous stunts of them all. I can’t believe it, but know it’s true! I’m glad the last performer featured here was able to retire, and have a normal life afterwards. I really love the opening shot at the top, and would like to buy those books you provided the links for. Thanks so much!