Remembering My Father and World War I

Veterans Day. At 11 a.m. a wreath is laid at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, marking the hour the fighting ended in World War I — November 11th — known originally as Armistice Day.

At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, the guns on the Western Front fell silent, ending one of the greatest military slaughters in world history.

British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (1957-1963) said one time that the only reason he was prime minister was that all the men of his generation who would have been had been left on the battlefields of France.

World War I was called — no doubt out of hope — “The War to End All Wars.”

It obviously did not end all wars. See the history books for World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq (two wars there), Afghanistan, and a distressingly long list of others. But the Armistice did stop the carnage wrought by the old principle of battle — to have your men attack the other side’s battle line. In World War I, with fixed positions and lines, those attacks came in waves, day after day, night after night — across a barren expanse known as “No Man’s Land” — into withering fire from the modern machine gun.

The carnage inspired a poem by a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, written shortly after he lost a friend at Ypres in the spring of 1915, when he saw poppies growing in the battle-scarred field:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

The doctor’s poem, “In Flanders Fields,” resonated.

To the point that 20 years later, when I was a little girl, artificial red poppies — usually red paper flowers for the lapel — were a common sight on Armistice Day, made by the American Legion to benefit veterans. They were often sold by veterans on the streets, a bit like the Santas who ring their bells by the Salvation Army black kettles at Christmas.

When I was a little girl, I also remember the casing of an artillery shell that stood on the end table in our living room, like an empty, unused flower vase. Shiny metal, brass I think, perhaps 16 inches high and four or five inches round.

It took a few years for me to link the unusual metal thing on the end table to the story my father, who served in World War I, liked to tell about being sent overseas and writing home to tell his mother where he was stationed. She was so relieved to learn he’d not been sent up to the front, that he would be “safe” stationed at an ammunition dump. She failed to appreciate the dangers.

These World War I incidents and memorabilia were part of my childhood.

When people spoke of “the war” back then, it was World War I. Years later, “the war” became World War II. And still is to “The Greatest Generation.”

I may be a child of “The Greatest Generation,” but my childhood memories are of World War I, its songs playing on the radio still. The sad “Roses of Picardy.” Or, “There’s a long, long trail a winding … into the land of my dreams.” George M. Cohan’s “Over There” was still played sometimes and, occasionally, a whimsical offering by Irving Berlin, who would later give us “God Bless America.” An expression of the everyday soldier starting his day of service to his country, “Oh, how I hate to get up in the morning.”

“Roses of Picardy” by Mario Lanza (Uploaded to YouTube by Megamusiclover1234)

Music was a natural part of my memories. My father played the saxophone in a band in his college years, and during the interregnum in France. I think that the guys in the band, or most of them, went off to war together, played overseas together, and returned to college — this time the University of Michigan — together. I know they took basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, for my father often told the story of the time they played for a local town dance.

They were going through their usual repertoire, which included a medley they went into as easily as they’d done a hundred times before. But this time they were only a few bars into one of the songs when the dancers paused and turned in their respective places on the dance floor to glare at the band with downright mean stares. They then stalked off the dance floor, often with a parting angry glance over their shoulders.

Too late Daddy and his buddies realized they were playing “Marching Through Georgia.”

As a friend of mine from Georgia said, speaking of that time, “There were still grandmothers in town who remembered Sherman.”

Daddy often talked about places he visited before being shipped home. Nothing like a Cook’s Tour of France and its close neighbors, but I remember his mentioning the town of Nancy and/or Nantes. And he ventured, although not too deeply, into the Alps.

He returned, as noted, and transferred to the University of Michigan, where he met my mother. And his life slipped into that of a young man embarking on his life in his early twenties.

Not all the veterans of World War I were so fortunate. Those who had left their jobs to serve their country returned to find their jobs had been permanently filled. And it left such a stain that the United States Congress decreed — formally written into law — that those who served in World War II (and all subsequent wars) would get their jobs back when they returned.

Not just a job. The job they’d had.

When I started at the Chicago Daily News as a copygirl in December 1944, there were around six female reporters my first year. They had been hired to replace the guys who were away fighting for their country. When the war ended and the guys returned, two of the women were so good they were kept on, and the staff expanded. The others cleaned out their desks and the guys who’d once been there sat down at their typewriters as before.

Congress also promised anyone who served a college education, in what came to be known as the G.I. Bill. And with the war’s end, colleges and universities across this country changed once again: during the war, regular students had been replaced by servicemen learning about pre-flight training, navigation, the fine art of a bomb sight; after the war, students found their ranks expanded by former G.I.s taking advantage of the opportunity to get a college degree.

It may be common today. But it was a rarity before World War II.

The G.I. Bill also made it possible for veterans to buy homes with little or no down payment and the government backing the mortgage. That’s why the Levitt towns and subdivisions with all those cul de sacs sprouted outside cities. Hundreds and hundreds and still more hundreds of veterans were able to buy homes.

In that respect, beyond the political alliances and treaties and missteps that led to World War II and its legacy, World War I had a major impact on life in this country. Everyday life. The determination to do right — this time — by all those who had served.

And today it’s almost forgotten. Only the anniversary date of its end is remembered, and it’s no longer Armistice Day.

Now it’s Veterans Day.

But still a day to pause — particularly, at 11 a.m. — to remember those who served.

Which is what this nation does.

In fact, some years ago when Congress decided that holidays should, whenever possible, be celebrated on Mondays so people could enjoy long weekends, the outcry from veterans and veterans’ groups about changing Veterans Day was so great that Congress had to change the date back to November 11. It wreaked havoc for a couple of years, however, because of the calendars that had been printed before the outcry.

A small price to pay, however, for a national holiday of such significance being observed on its anniversary date.

From those long ago days of childhood and the story about playing “Marching Through Georgia” to a reunion long years after the end of World War II, I remember Daddy talking about the war. Teaching me a few French words (not parlez-vous Francais?). And threaded through it all, his buddies.

They were just names to me until they gathered once again in our home in Wilton, Connecticut, one beautiful day in 1960, and brought new meaning to the word reminisce.

A happy time, created out of war time.

Featured image: Mike Pellinni / Shutterstock

How Fundraising Fraud Became Big Business After World War I

In January of 1925, the House of Representatives passed a resolution to investigate the finances of a charity called the National Disabled Soldiers’ League. Incorporated in 1920, the league purported to “foster and perpetuate national patriotism” by working to improve the lot of disabled soldiers, sailors, and marines.

The NDSL had raised around $290,000 in the prior three years — mostly through mail campaigns in which they sent envelopes containing pencils to prospective donors to solicit donations. The problem was that they could only prove that about 10 percent of that money had gone to the actual cause. The other 90 percent likely went into the pockets of three men who took over the league less than a year after its founding.

In the hearings, a select committee — chaired by Hamilton Fish, Jr. — observed evidence of the NDSL’s unprincipled dealings. They had held excessive, bacchanalian annual conventions, after which they stiffed local hotels, restaurants, and entertainment workers. They were denounced by prominent men (like Senator William Calder and vaudeville star Edward F. Albee) who had once held positions on their advisory board. They dodged all government investigations into their finances, refusing to show their books. The league even cheated the Donnelly Corporation, the company that made their pencils.

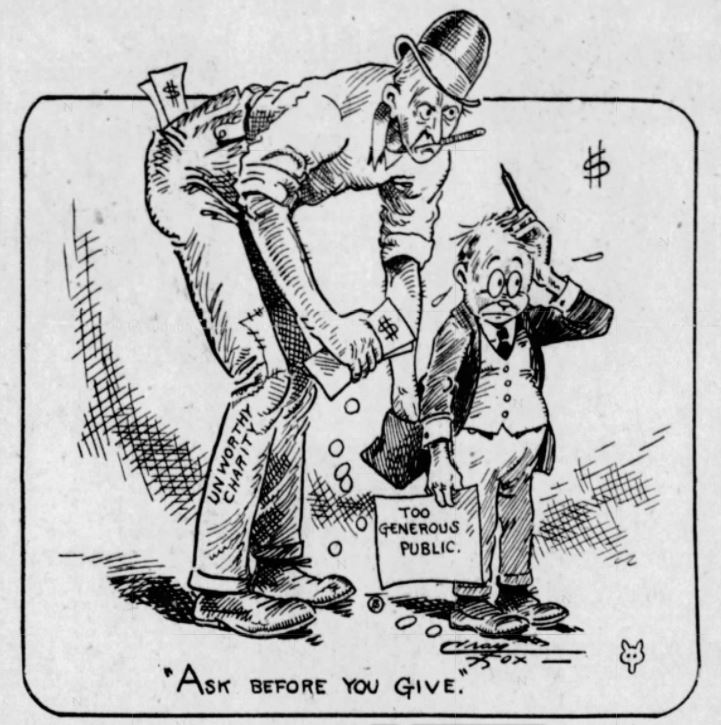

The NDSL was a perfect example of the kind of organization that soft-hearted Americans were warned against in the years after the First World War. A 1922 article in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle told of “the suavely professional solicitor of tear-stained checks for shady causes” and advised readers to “ask before you give.”

Whether ineffectual charities were nefarious scams or just mismanaged, they were making a whole lot more money after the armistice. The drives that raised funds for the war effort and foreign relief during the war had inadvertently created an army of consultants ready to offer their services to every church, league, and club in the country.

Raising money for a cause — or, pejoratively, systematic begging — was a new sector in the economy of sentiment, and it was big business.

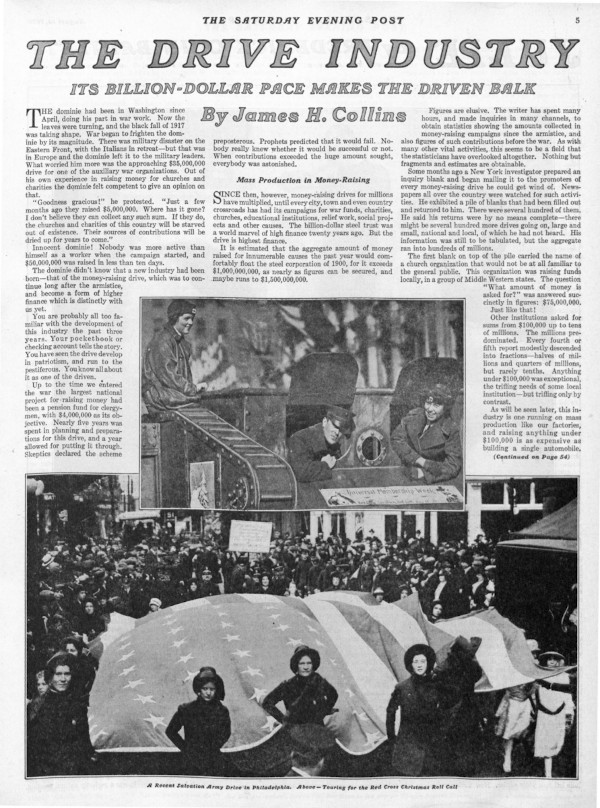

Writer James H. Collins called it the new “drive industry” when he wrote about it in this magazine 100 years ago, saying fundraising had “become a form of higher finance which is distinctly with us yet.” According to his reporting, the largest national fundraising effort before the war had been a long-planned drive for a clergy pension fund with a goal of four million dollars. But more recently, such multi-million-dollar drives had become commonplace, and — in the year since the war ended — he counted 1 to 1.5 billion dollars raised for various causes around the country.

He noticed that people were beginning to grow weary of fundraisers. “You’ve seen the drive develop in patriotism and run to the pestiferous,” Collins wrote.

Before the 20th century, charitable fundraising in the U.S. for any given cause was accomplished mostly through soliciting a handful of wealthy donors. Charles Sumner Ward and Lyman Pierce, in their work for the Young Men’s Christian Association, pioneered the method of a fundraising campaign targeting the masses. Then, systematic, crowd-sourced fundraising took off. As public relations historian Scott M. Cutlip wrote in Fund Raising in the United States, “World War I brought intensive, hard-hitting campaigns that raised millions and established philanthropy on the broad, democratic basis that characterizes it today.”

“War bazaars” were popular events for getting dressed up and indulging in some shopping and entertainment for the cause of the doughboys overseas. Or at least that was the idea. In at least one case, such an event raised almost $80,000, and a New York World investigation found that only $754 went directly to the “great war charity.” The rest was depleted by expenses for the event. In a 1917 call for this kind of graft to be avoided by funneling all war expenses through the government, The Washington Times decried the “philanthropic camouflage” of “gentlemen whose business is urging others to contribute.”

Several methods for collecting money became ubiquitous in the U.S. by 1920. Coin boxes to collect loose change were installed in all kinds of businesses. On “tag days,” volunteers — like women from the “Anti-Saloon League for enforcement of the prohibition laws” in Nashville — would swarm street corners with buckets soliciting donations. Passersby who gave would receive a “tag” pin, marking them against further harassment. Often, donors’ names and contributions were printed in the local paper after a drive for Belgian relief or war bond sales.

Sometime during the war, the tactics associated with money drives became a means for padding resumés and charging varying amounts of commission. A column in Topeka’s Capper’s Weekly in 1920 claimed that more than 10,000 men and women had entered this new field as directors, collectors, and publicity agents: “The war showed the possibility of this modern method of getting money. It has also created a new industry or profession, that of the drive-making.”

The explosion in American fundraising necessitated some standards for best practices. Giving up 30 percent of funds to a campaign manager and publicist (as Collins described one hospital doing) was unnecessary, let alone the 50 to 70 percent reported from various other campaigns. Five to ten percent was reasonable, according to most experts, with costs much more or less signaling dishonesty or inefficiency.

The National Information Bureau (later named the National Charities Information Bureau) was formed as a sort of cooperative watchdog group in New York in 1918. The bureau released eight guidelines for giving, including making sure a charity keeps good records with a C.P.A., that they aren’t duplicating the work of others, and that they avoid “remit-or-return” schemes like sending trinkets in the mail. In 1920, according to Collins, the bureau only approved of 124 of the 1,021 national money drives in the U.S.

For attentive donors, the National Disabled Soldiers’ League wouldn’t have passed the bureau’s sniff test. The league failed to produce financial records throughout the congressional committee’s investigation,they relied on remit-or-return mailing for fundraising, and they supposedly engaged in the work of advocating for veterans without coordinating with similar organizations. In 1921, the Disabled American Veterans of the World War of Minneapolis denounced the NDSL and its grifter kingpins, where they claimed “the officers … receive 90 percent of the dues as salaries.”

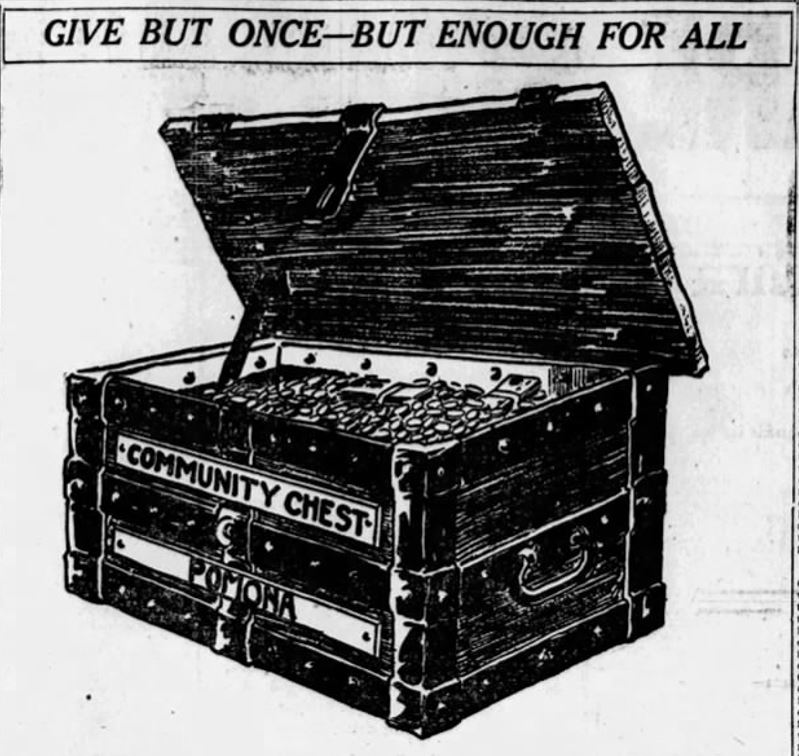

Another effort that aimed to breed more efficiency in charities was the popular Community Chest system. Before it became known primarily as a serendipitous card from the Monopoly game, the Community Chest was an organized group of community members who would direct lumped donations to local charities to eliminate duplication of efforts and competition. Cleveland created the model for a Community Chest program in 1913, and the idea spread around the country throughout the early century. Eventually, they merged to form the United Way Foundation, one of the largest non-profits in the world.

As technology and media have progressed, fundraising methods have evolved to suit ever more platforms for giving. War bazaars gave way to telethons just as mailing lists have given way to powerful donor relations software. Even as United Way marked a centralization of fundraising for charities in the latter half of the 20th century, the rise of the popular site GoFundMe — where one in three campaigns seeks to cover individuals’ medical costs — is a decidedly decentralized trend in giving.

That the drive industry is still “distinctly with us” after more than a century is a given. Though it has expanded and adapted to the changing world, charitable fundraising can still be approached with the same rules the National Information Bureau laid out in 1918:

After the congressional investigation into the NDSL, the House special committee recommended the case to be turned over to a Federal Grand Jury. They found that three men, John Nolan, James McCann, and Kenneth Murphy, were in complete control of the finances, and their bank accounts were receiving suspicious deposits while the league’s money was unaccounted for. The next month, the Postmaster General barred the NDSL from using the mail. “Nothing is sacred to these crooks,” the Buffalo Courier printed. “Religion, patriotism or anything else they will capitalize so long as they can see in it a chance to get money.”

Five years later, Murphy was at it again, planning a fundraising campaign to build a memorial to the Allied General Ferdinand Foch. He had even talked Franklin D. Roosevelt into joining the committee. Hamilton Fish, Jr. heard that familiar name and publicly denounced the project, calling attention to Murphy’s previous scams with the NDSL. “I hope in the future,” he said, “that members of the House and Senate, who permit the use of their names for these fake veteran organizations, will take the trouble to find out something about them.”

Today, the fundraising industry is sprawling and complex. Charities and non-profits — whether dubious or entirely dependable — still vie for well-meaning Americans’ dollars. Graduate students in philanthropic studies take courses in fundraising processes and donor behavior, not to mention the contemporary craft of grant writing.

It would, perhaps, have come as a surprise to enthusiastic early-century advocates of the Community Chest to know that in 2017, Brian Gallagher, CEO of the centralized progeny organization United Way, would receive more than $1.6 million in compensation. United Way maintains that it is comparable to CEO salaries at other non-profit organizations of similar size, but that might just further illustrate how competition has played a role in building the so-called “non-profit industrial complex.”

There are charities in the U.S. for animals, veterans (and sometimes both), medical research, homelessness, hunger, and too many environmental organizations to count. Several watchdog organizations, like CharityWatch, Charity Navigator, and the Better Business Bureau, provide reports on many of these — including financial audits, board makeup, and quick figures on spending.

On GoFundMe or other similar websites, it’s a philanthropic wild west. You can donate to a family who has just lost their house to a fire or a college student who has been diagnosed with brain cancer or any number of bizarre, cheeky, or politically-charged fundraisers. GoFundMe pages are vetted inasmuch as individuals provide and request evidential information. Although the company claims that less than .1 percent of the fundraisers on their site are fraudulent, plenty of high-profile scams have become big news stories over the years.

The current, entrenched system that makes a philanthropist out of everyone might seem inevitable and commonplace, but Americans living before war drives and tag days would never have seen it coming. They would have reacted with great suspicion to anyone soliciting them for their hard-earned dollars or mailing them pencils. What they didn’t yet understand was that their empathy for the downtrodden and poor could fuel the makings of a fantastic business model.

Featured image: Library of Congress, 1920, National Photo Company Collection: TAG DAY UP TO DATE IN WASHINGTON D.C. No longer can the citizen who rides in an automobile feel secure on tag days. In the past the lowly pedestrian has been the one to “Come across” while the automobilist was comparatively safe. Washington society ladies sprang a new one today in selling tags for the benefit of Columbia Hospital. Fair damsels on horseback “Held Up” automobiles while their sisters on foot “Worked” the sidewalks. Photo shows Miss Ellen Messer receiving a liberal contribution from a surprised automobilist.

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: America Invades Russia (100 Years Ago)

100 years ago, America invaded Russia in an effort to cut off the Germans and defeat the Lenin’s Bolsheviks. Find out what happened in this lesser known World War I conflict.

See more History Minute videos.

The Saturday Evening Post History Minute: How World War I Changed America

November 11 commemorates the armistice signed between the Allies and Germany, which officially ended World War I on the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.” None who fought are still alive to share their stories, but the Great War actually produced many lasting changes in America.

See more History Minute videos.

When We Were Heroes

This excerpt is from the article “Homo Americanus in Gay Paree” by Elizabeth Frazer, which appeared in the November 2, 1918, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Suddenly a shout — no, not exactly a shout; rather, a big happy hurrah — burst simultaneously from thousands of grateful happy hearts. Here they come! Les Americains! Here they come! Strong emotion swept the crowd like a breeze. Vive l’Amerique! Vive les Americains!

And all that excited sea of souls laughed and cried and shouted and sobbed and rocked in glad exultation over these fine, big, clean garçons who had fought so splendidly, so desperately, so victoriously beside their own brave poilus.

It was American troops who stemmed the tide, who closed the road to Paris. They paid the price in blood, and the price was high. For that single episode showed both friends and foe where the war’s balance of power lay.

On they came, their bayonets glittering in the sun, their faces wreathed in smiles, their eyes — well, not quite straight dead ahead! For who can discipline his eyes, when a bombardment of roses or a barrage of violets hits one straight on the nose? There are garlands of roses round their necks, roses behind their ears, roses in their cartridge belts, roses in the nozzles of their guns, which lately spouted flame and shortly will again.

But today is Fourth of July in Paris! And these soldiers have earned this day of joy.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

100 Years Ago: A President Silences His Critics

Earlier this month, President Trump, angered over critical reporting by journalists, pondered via Twitter whether he should revoke their press credentials. This bitter feud between press and president has raised an old question: Does the president have the right to silence people who criticize him or his policies?

Congress debated that question 100 years ago and believed so strongly in such executive privilege that it passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts to stifle dissent in America.

President Woodrow Wilson expected criticism after he asked Congress to declare war on Germany, sending America into World War I. He had, after all, been elected on his record of keeping the U.S. out of the war. Now he’d committed the country to that contest, and he knew he’d need strong public support for the war effort. He would tolerate no criticism that might discourage military enlistment, the sale of war bonds, or cooperation with rationing programs. He needed loyal Americans — loyal, that is, to his plans.

But there were strong anti-war feelings among pacifists, socialists, and union organizers, as well as immigrants. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were eight million first- and second-generation Germans living in the U.S. Many retained a strong attachment to the land of their birth. Wilson believed they might dampen the war effort with pro-German sentiments, and he feared German agents hid among them, embedded at all levels of American society. German saboteurs had already destroyed a major munitions depot in New York Harbor.

Wilson proposed a bill to silence criticism of the war. The result was the Espionage Act, which became law on June 15, 1917, and prohibited anyone from aiding America’s enemies in wartime or interfering with the armed forces and its recruitment efforts. It also made it illegal to make false statements that disrupted military operations, promoted the enemy’s success, or led to insubordination or disloyalty.

But the Espionage Act didn’t end the dissent. A Montana rancher publicly called President Wilson “a Wall Street tool” and said he’d leave the country rather than go to war. He was tried under the Espionage Act but acquitted on appeal because he didn’t directly affect war efforts. In response, the U.S. attorney general called for a law to broaden the Act’s powers.

So Congress extended government control to affect speech and writing. The Sedition Act of 1918 made it a crime to use “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about America’s government, its flag, or its armed forces. Making any statement that inspired contempt in others for the government or its institutions was also outlawed.

Theodore Roosevelt protested the law, saying it was “a proposal to make Americans subjects instead of citizens.”

But some legislators thought it didn’t go far enough to root out dissident thinking. A New Mexico congressman was disappointed the Act didn’t provide the death penalty. And an unsigned editorial in The Washington Post stated, “Enemy propaganda must be stopped, even if a few lynchings may occur.”

The Saturday Evening Post editors supported the Act. The government didn’t need a sedition law to protect itself, they said, but it had to show patriotic Americans it wouldn’t allow anyone to criticize their loyalty or the national cause. This explanation probably referred to the mobs of outraged citizens who had attacked and even lynched people suspected of disloyalty.

It was in the Post’s best interest to support the law at the time. Had the editors been critical instead, the Sedition Act would have empowered the postmaster general to block all delivery of the Post, as he had with other publications.

Two thousand cases were tried under the Sedition Act, half of which resulted in conviction. It was invoked most often in Western states, where it was used frequently to prosecute members of what was considered a radical workers’ group, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The Sedition Act was repealed in 1920 and the offenders were pardoned, though well after the war had ended. The U.S. attorney responsible for the pardons praised the government for detaining a number of dissidents in prison after the war “to set an example of firmness that will go down in history as a warning to those who in the future might be inclined to harbinger and harass the government.”

As much as the president would enjoy being able to legally silence his detractors, their public criticism is still protected by law.

Featured image: Shutterstock

News of the Week: Facebook’s Future, Han Solo’s Past, and a Bunch of Flowers You Can Eat

Zuckerberg!

We all go through a lot of painful times in our lives. We endure broken bones and root canals and tax audits and maybe even some particularly bad paper cuts. When I was a kid, I had such a bad earache one night that I had to go to the emergency room. (Oddly, the pain went away while I was sitting in the waiting room.)

But there are very few things in life as painful as watching people of a certain age who know nothing about technology talk about technology. That was the case this week when several senators and representatives questioned Mark Zuckerberg about the latest privacy scandal involving Facebook.

I’m not a fan of social media (you may have read about that in this column 2, 3, or 5,000 times), but it would have been better to get some questions from people who actually knew something about, well, social media. Sure, some of the questions were clever, some incisive, and some even focused on Facebook’s power, but too many questions showcased a lack of understanding of not only how Facebook works but how internet advertising works in general, especially if you love chocolate. Some of the people asking questions actually thought that FaceMash — a joke version of Facebook from when Zuckerberg was still in college — was still in business.

It’s not that a lot of the officials asking questions didn’t know how algorithms work or how cookies are stored on a browser. A lot of people don’t get that stuff. But if you’re holding two days of hearings questioning the CEO of a company that shared the data of 87 million of its customers, you would hope those people would know that when you “reboot,” it doesn’t mean you put your boots on again.

Mark Zuckerberg is now living out every young person's worst nightmare: trying to explain how tech stuff works to the nation's elderly

— Robby Soave (@robbysoave) April 10, 2018

It was almost enough to make me feel bad for a multi-billionaire. Almost.

Solo!

I have a problem with the Star Wars movies. I haven’t yet seen the most recent film, The Last Jedi, but I did see all of the films before it and something really bothers me.

(This is where I put a space and give you plenty of notice that SPOILERS FOLLOW.)

Han Solo dies in The Force Awakens. Now, this in itself isn’t a big deal, since heroes die in movies all the time, but it makes it hard to watch the first three in the series (A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi). If you go back and watch them now, you see that when they succeed in their mission and Han and Princess Leia have a family, it doesn’t lead to peace and happiness in the universe. It leads to the birth of their son, who grows up to kill a bunch of people, lead a new war, and eventually kill his father Han Solo. That’s really an odd thing to have in the back of your mind as you watch everyone smiling and Ewoks dancing at the end of Return of the Jedi.

Anyway, here’s the trailer for Solo: A Star Wars Story, the prequel that depicts the early adventures of Han (played by Alden Ehrenreich). It’s directed by Ron Howard and opens on May 25.

111?!

The world’s oldest military veteran (and probably the oldest person in the U.S.) just took a ride on a private jet.

Richard Overton of Texas served in the Army during World War II, and he recently received a free trip to visit the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. He still lives in Austin, Texas, in the same home he built 70 years ago.

It’s really amazing to think that Overton was born in 1906. That’s the year of the great San Francisco earthquake, six years before the Titanic sank, and eight years before the start of World War I. Teddy Roosevelt was president.

Herman Wouk Deserves a Medal

It’s not 111, but 102 years old is pretty good, too. That’s the age of writer Herman Wouk, famous for the novels The Caine Mutiny, The Winds of War, and War and Remembrance. He even wrote for comedian Fred Allen in the 1930s and ’40s! There’s a petition on the White House website to honor Wouk with a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Wouk turns 103 next month, so let’s get that medal for him now. He needs 100,000 signatures before the White House will consider it.

Friday the 13th

If you’re the superstitious type, you’re probably spending today avoiding black cats, ladders, and mirrors (you don’t want to chance breaking one). Maybe you’re so paranoid that you don’t even want to take any risks and you’re reading this on your laptop while curled up in bed.

You’ve probably wondered how Friday the 13th became Friday the 13th. If you’re really young, you might think it has to do with the gory film franchise (it doesn’t). Instead, it involves the Knights Templar, Judas Iscariot, and/or the number 13 itself.

If you do fear the day, you’ll be happy to know there’s a name for your fear: friggatriskaidekaphobia. That’s something you can tell people today. You can explain that you’re not crazy, because there’s actually a name for it.

RIP Susan Anspach, Cecil Taylor, Soon-Tek Oh, Chuck McCann, and Mitzi Shore

Susan Anspach was an actress who appeared in movies like Five Easy Pieces and Play It Again, Sam and TV shows like The Slap Maxwell Story and The Yellow Rose. She died last Monday at the age of 75.

Cecil Taylor was an acclaimed jazz pianist known for his innovative style. He died last Thursday at the age of 89.

Soon-Tek Oh appeared in a million TV shows and movies over the years. Too many to list here. He died last Wednesday at the age of 85.

Chuck McCann was a veteran comic and actor who had a really varied career, from roles in movies (The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter) and TV shows to classic, long-running TV commercials. He even originated the voice of Sonny, the “Cuckoo for Cocoa-Puffs” bird. He died Sunday at the age of 83.

Mitzi Shore was the owner of The Comedy Store in Los Angeles, where many comics, including Robin Williams, David Letterman, Jay Leno, Billy Crystal, and Roseanne Barr, got their start. She was the mother of Pauly Shore. She died Wednesday at the age of 87.

Quote of the Week

“We had to decide, do we go back into the lobby or into the elevator? Those are terrible options when what you’re looking for is a hospital.”

—Late Night host Seth Meyers, whose wife went into labor in the lobby of their apartment building last weekend

This Week in History

The Great Gatsby Published (April 10, 1925)

The F. Scott Fitzgerald novel is on most “best novels of all time” lists. You can read it for free at the Internet Archive.

Apollo 13 Launched (April 11, 1970)

The seventh manned Apollo mission almost ended in tragedy when an accident occurred around hour 56. It was the basis for the 1995 Tom Hanks movie Apollo 13 and the source of a famous quote that a lot of people get wrong.

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Men Working (April 12, 1947)

Stevan Dohanos

April 12, 1947

My favorite detail of this Stevan Dohanos cover is that the guy hasn’t even finished painting the “Men Working” sign.

Spring Recipes

To me, spring food = boring food. In the winter we have enticing, filling comfort foods like pasta and chili and steak and soups. Spring means … salad?

But if we’re going to eat during the warmer months of the year — and the latest medical evidence suggests we should — let’s make sure they’re the best salads we can eat. Here’s a recipe for a classic Cobb Salad, which seems to have everything in it but chocolate and potato chips. Here’s a Grilled Chicken Caesar Salad, and our own Curtis Stone has a recipe for an Apple Salad. And here’s a list of edible flowers (yes, flowers) you can throw into your favorite salad. Dandelions are okay, but stay away from those azaleas.

Supposedly, if you eat a lot of salads, they’ll help you live longer. Maybe to 102 or even 111.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Taxes Due (April 17)

Spring is also tax time! You get two extra days to file this year because the 15th is a Sunday and the 16th is Emancipation Day in Washington, D.C.

National High Five Day (April 19)

Maybe you can give yourself one when you finish doing your taxes.

Classic Covers: World War I

As we all know, we have too many wars to remember. Last month on this website, we ran a story on a Post newsboy who was killed in World War I. Seeing the photos from the article inspired me to show some World War I covers from both The Saturday Evening Post and Country Gentleman, a longtime sister publication. Some are well known, but I’ve discovered a few surprises. All are intended as a tribute to our veterans of today and yesterday.

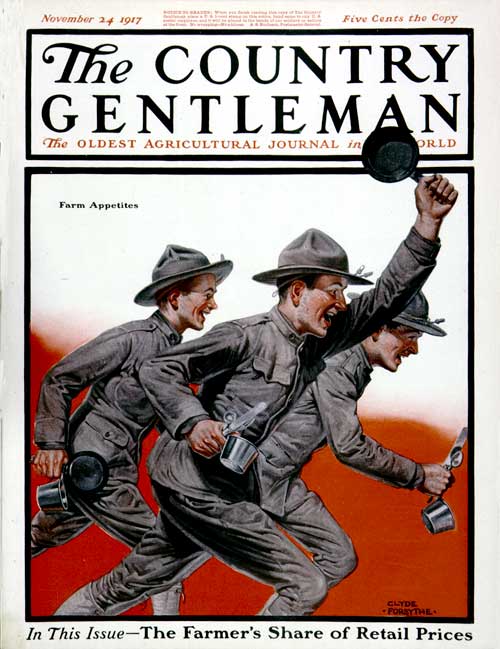

Farm Appetites – Clyde Forsythe – November 24, 1917

We have plenty of poignant wartime covers, but this one is fun! These are hearty farm-boys-turned-soldiers, and the painting is appropriately named: “Farm Appetites.” It was done by cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, a friend of Norman Rockwell. In fact, it was Forsythe who encouraged the reticent, nervous young Rockwell to try to sell a cover to the venerable Saturday Evening Post. So Forsythe not only painted history, he helped to make it.

Women Work for War – Charles A. MacLellan – July 20, 1918

Charles A. MacLellan

September 8, 1917

And who, pray, worked the land while the male farm hands were fighting the war? The “women’s land army”, that’s who. Some were country girls, others were out of their element working farms, but the women of the U.S. and Europe wanted to do their part back home.

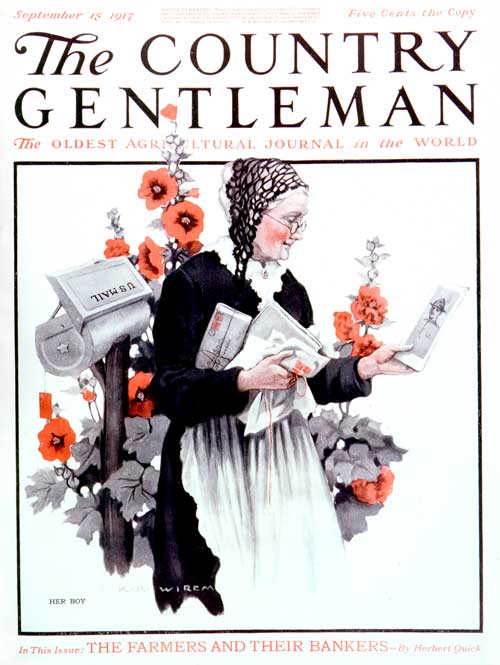

Her Boy – K.R. Wireman” – September 15, 1917

Another seldom-seen Country Gentleman cover shows a proud mother at the mailbox, receiving a photo of her son in uniform. Let’s hope he’s back at the farm soon. This was by artist K.R. Wireman.

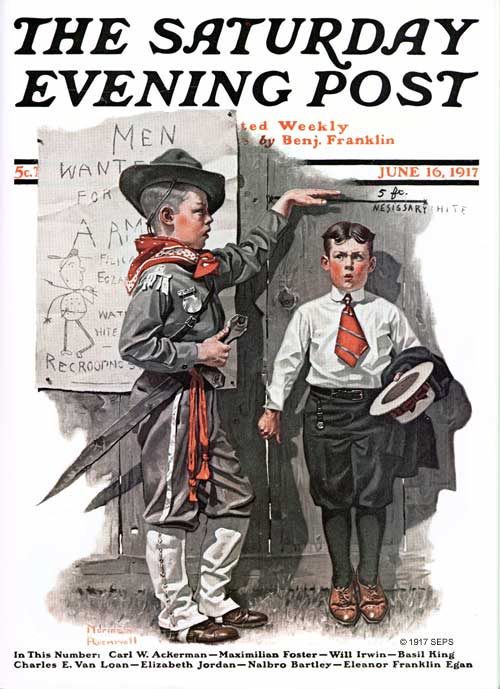

Necessary Height – Norman Rockwell – June 16, 1917

Back at The Saturday Evening Post, a gent we all know and love, Norman Rockwell, was also recognizing the war in his art. Only about 22 himself at the time, Rockwell shows us that even the youngsters were getting into the war effort. Playing recruiter, a boy (notice the “recruiting poster”) seems to be questioning the qualifications of a vertically challenged applicant.

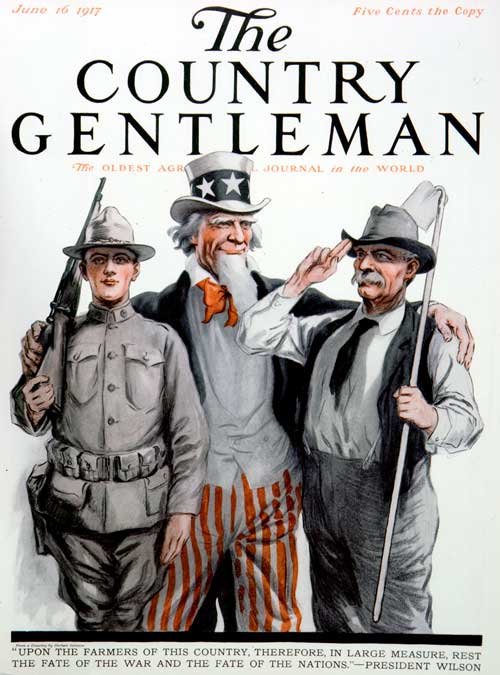

Uncle Sam – Herbert Johnson – June 16, 1917

This trio was vitally important to the nation in World War I. The American soldier, good old Uncle Sam and the American farmer. This was from a painting by Herbert Johnson, a well-known political cartoonist for both the Post and Country Gentleman.

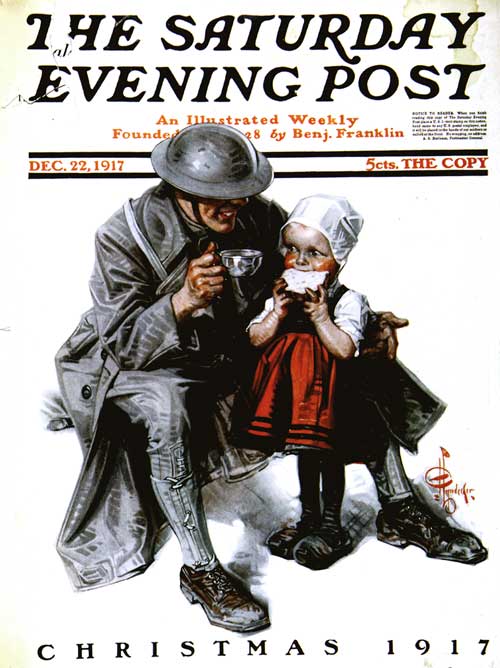

Soldier’s Christmas – J.C. Leyendecker – December 22, 1917

I can’t leave without sharing my favorite World War I cover, “Soldier’s Christmas” by J.C. Leyendecker. A soldier is sharing his meager holiday meal with a tiny French girl. Can’t help it – gets me every time.