An Automobile Genius on the Secrets of Innovation

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

This year the company for which I work — General Motors — is celebrating its 50th anniversary. For 40 of those years I have been a consulting inventor for the company. We sometimes hear it said that necessity is the mother of invention. If that were true, then it might be said that for the last several decades I have been working my head off because of necessity.

I can’t go along with this maxim altogether. Necessity was certainly not the mother of the airplane. At the time the Wright Brothers were inventing the airplane there was no widespread clamor to fly. People did not believe it was necessary. The Wright Brothers just thought they knew how they could do it and so they went ahead and thereby opened up a huge new field.

It might be argued that it has not been necessary to invent the automobile or to improve it through many inventions in the last 50 years. We would have lived with no more than the horse and the buggy. But I believe we are all thankful for 50 years of improvement in the automobile, and I am sure we will keep trying for more improvement just as hard in the next 50 years.

I am a little afraid of reminiscing. But to measure the possibilities of the next 50 years, it may be worth looking back over the last 50. It is amazing what the invention and development of the automobile and its applications have done to influence the habits and customs of our people in this period. Since 1908, manufacturers in this country have produced 160 million motor vehicles, and today the automobile creates 10 million jobs in highway-transport industries, more than one of every seven existing jobs. It has created a quarter of a million businesses like motels and service stations, and influenced the building of 2 million miles of roads. It has made deep changes in how people travel, how farmers grow and market crops, and where schools are built.

The automobile industry pays about $8 billion a year in taxes. Almost one quarter of the retail price of each vehicle is tax money. This is an enormous burden, yet the automobile industry has produced the greatest transportation system the world has ever seen. One of the most important reasons for this growth has been the industry’s willingness to change its product and its production methods to suit customers’ demands. The industry has been willing every year to design and build new tools which can produce more and better cars.

I do not advocate change for the sake of change, nor do I say that a new thing is necessarily better because it is new or suddenly popular. But if there is one thing the automobile has taught Americans in the last 50 years it is to expect constant improvement in the product. In America we must constantly change and improve or fade away.

Too often people believe that change comes about through the simple process of handing a problem to a research laboratory where an answer is produced mysteriously but promptly. There is no such magic in research. Discovery and invention come only by hard work, disappointments, innumerable failures, and very often the consumption of much time and money. Research is based on patience, skill, and practice and more practice. A theoretical physicist may develop an accurate formula for the curve of a baseball in flight, but it takes a pitcher years of practice to control the curve.

Since its inception the automobile industry has worked and practiced to lift the automobile from the status of a rich man’s toy. It was only a few years before General Motors was born that Ransom Olds discovered one of the secrets of mass production — progressive assembly. And it was just 55 years ago that Henry Leland, who was then head of Cadillac, demonstrated that automobile parts could be made interchangeable. These two developments were basically important to the automobile, but they alone did not make the product a perfect one. Leland understood this very well.

At that time the automobile was cranked by hand, which was not a job for women and usually meant they were relegated to the backseat as passengers. Hand-cranking was not popular with men, either, since there was a constant risk of broken arms. Leland disliked this imperfection and when a dear friend of his died as the result of an accident during hand-cranking, he sent me an invitation to visit Detroit and discuss the problem of making car-starting a safer operation.

This was one time when I might agree that necessity mothered an invention, because in a moment of weakness I told him that I thought a car might be cranked with an electric motor driven from a storage battery. Having made the rash statement it was up to me to produce it, and I worked for months in my small laboratory which was part of a barn in Dayton, Ohio. Eventually we did produce an electric starter, a modification of which became production equipment on the 1912 Cadillac.

This outraged the electrical-equipment engineers. They looked at their formulas and said that it was impossible, that we would need batteries and an electric motor larger than the engine itself and wires five times as heavy as we used. But they were thinking about continuous-running electric equipment. But we were not planning to transmit current 100 miles or work our electric motors 24 hours a day. We wanted a spasm of power, a big torque for a short time, and after the engine was turned over and started, the little starting system could lie back and rest and be recharged for the next start. So we disregarded the power rules and made driving possible for millions of people who couldn’t or did not want to hand-crank an engine.

Ten years later we could manufacture automobiles at the rate of one a minute, but they were not getting to the customer at that rate. It took one or two weeks to paint the car because the system that had been used on carriages was being applied to automobiles. The increased production resulting from the growing demand for closed cars could not possibly be met by using the old finishing methods.

Eventually the answer was found in the chemist’s test tube, although the you-can’t- do-it boys were on our necks all the time telling us we were wrong. Now, instead of several weeks to paint a car, it takes an hour to spray on the required number of coats of quick-drying, durable, colorful lacquer. The bottleneck to customers’ demands was broken.

In this business of ours you never solve one problem without, nine times out of 10, coming face to face with another one. After we had put electric starting, lighting, and ignition on the Cadillac we became sitting ducks for attacks aimed at us by the people whose toes we had stepped on when we electrified the automobile. In those days the quality of gasoline was hit-or-miss and the quality went down as automobile production went up. Engines began to knock all over the place. Naturally our competitors blamed the increasingly prevalent knock on our new ignition system.

In order to defend ourselves it was up to us to find out what really did cause knock. It was a problem that had also arisen with the Delco farm-lighting systems which I had originally devised so that my parents could have light and running water on their Ohio farm. To do this job we put a fellow inventor, Tom Midgley, to work studying this annoying matter of knock which was keeping us from increasing the compression in our engines. Happily neither Tom nor I was an orthodox chemist or thermal engineer, so we were wholesomely ignorant of the obstacles. We had a fine chance to make some informative errors in this field.

In the period before World War I, we had found out first just when knock occurred in the combustion chamber. It was after the ignition spark; and not before, as everyone had supposed. With this knowledge in hand we started a series of experimental treatments of the fuel. I remember that the first one was the introduction of coloring matter based on the heat-retaining characteristics of a certain flowering plant. We got a promising result, only to learn by checking with another substance that color had absolutely nothing to do with it. Nevertheless we learned something from that, and as we went on to test other additives a pattern of behavior began to appear.

The motoring public will never know how lucky it was that we did not stop in the middle of our experiments. The pattern indicated that the compounds of the heavier elements were most effective in squelching knock. We found two or three that were so good we might have been satisfied with their performance if it had not been for one thing — they smelled terrible. They smelled so bad and the odor was so lasting that the men in the laboratory who handled them were on the verge of becoming involuntary hermits. They didn’t dare go to the movies. But with the pattern leading us in the direction of the heavy elements, I suggested that we take a big leap and try the very heavy metal — lead.

The result of that leap was a whole bookful of trouble — and tetraethyl lead antiknock gasoline, which Midgley and his boys worked out and which is now known as Ethyl to everyone. Before we perfected Ethyl for widespread use, we had to develop a method of extracting huge quantities of the element bromine from the ocean. The chemists again told us this was impractical, since there is only one-tenth of a pound of bromine in a ton of sea water. But we found a way, and now we extract 120 million pounds of bromine from the sea annually. If you want to put a value on the result of our long hard search, in which the entire oil industry cooperated, you can do so in three ways. The superior fuel made possible more efficient high-compression engines. It permitted us annually to leave 25 billion gallons of fuel in our underground reserves which otherwise would have been burned. And at retail prices of gasoline the American motorist has been saving $5 to $8 billion a year.

You can see from just these few examples that the automobile industry was teethed on trouble. Complacency has no place in this business. You have to break out of the ruts if you want to survive. The fact that of about 2,500 makes of automobiles that have appeared only a handful are in existence today is a good illustration of what can happen if you design to suit yourself and ignore the wishes of your boss — the customer.

I am a great believer in the “double profit” system. The producer must make a profit to keep in business, but the customers’ profit must be ever so much greater. If you don’t believe some of these modern necessities, comforts, and conveniences have a definite value to you, just try doing without them. Suppose you were suddenly deprived of your car, electric lights, and power, or the telephone, radio, or television. What would you give to have them back?

—“Future Unlimited,”

The Saturday Evening Post, May 17, 1958

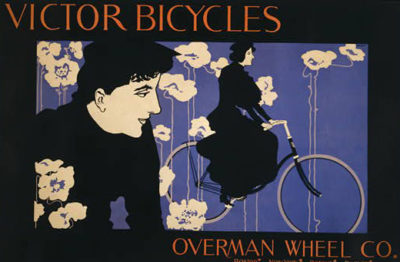

An Interview with Margaret Guroff on How Bicycles Built Our Highways

Margaret Guroff is the author of The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life (2016), from which her essay “How Bikes Built Our Highways” is adapted.

Margaret Guroff is the author of The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life (2016), from which her essay “How Bikes Built Our Highways” is adapted.

Ramona Whittaker: How did you become interested in bicycles and their impact on America’s highways?

Margaret Guroff: I saw a brief mention in a history book about how cyclists were instrumental in getting U.S. roads paved in the 1890s. Until then, I hadn’t really been aware of bikes as existing before cars, and when I started to look into the role of the bicycle in American culture, I found its influence all over—not only in the Good Roads Movement, but in the auto industry, the invention of the airplane, the development of consumer culture. The bicycle also influenced the way women dressed and it empowered women during 1890s when they were getting together to advocate for the vote.

RW: The mode of transportation became a game changer?

MG: Exactly. On bicycles, young women could get around without chaperones — which had been frowned upon before — and they could get where they were going under their own steam. Bicycling also helped people understand that exercise was good for you — something many Americans didn’t believe before the bicycle. They thought that if you did something that made your heart rate rise, you would damage your heart. A lot of people really didn’t know that if you exercise, it makes you feel stronger. And many doctors thought that you were born with a certain amount of energy. When you spent it, that was it. Doctors were very likely — particularly as adults got older — to say, “You just have to sit down, just chill.”

RW: Was that true especially for women?

MG: Yes. Proper women wore corsets to help them carry all their clothing — which could add up to 25 pounds of skirts, dresses, and stuff. A corset helped distribute this weight up and down their torsos. But all that weight and the constriction of a corset made it likely that if they stood up or moved too fast, they would faint. This created an illusion that women were weak and shouldn’t exert themselves.

RW: How did the bicycle change women’s fashion, and how did the public react?

MG: Dress reforms were actually proposed in the middle of the 19th century. Women’s rights advocates Amelia Bloomer, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton all decided to wear Turkish-style flowing pants that were weren’t constraining or heavy but were still very modest. They thought it was a much healthier way for women to dress, and they were trying to set a trend. They eventually had to give it up, because they were being harassed. Critics called the outfit a “bloomer costume.” They’d yell at these women and even throw things at them. So, bloomers didn’t catch on in the 1850s. But when the bicycle became popular at the end of the 19th century, women realized they couldn’t ride in their long, flowing skirts, and some of them started wearing the bloomers that had been advocated 40 years earlier. These women also were mocked. It’s not like it was normal for women to wear pants in 1890. A story on the front page of a tabloid called the National Police Gazette in 1893 carried the headline “She Wore Trousers” as if it was shocking that a woman would do this in public. The difference was that even though women wearing bloomers in the 1890s were getting the same kind of harassment as Amelia Bloomer did in the 1850s, they had a new motivation. They were willing to put up with mockery to be able to ride bicycles. Within just a few years, there were so many women riding bicycles that it became much more acceptable to wear pants or shorter skirts to do so.

RW: Did bicycles offer women a new form of independence and sense of freedom?

MG: Yes, it’s amazing. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” She saw clearly that the bicycle was motivating non-activists to take political action. They thought they were just having fun, but really were turning the culture upside down.

MG: Yes, it’s amazing. In 1896, Susan B. Anthony said, “Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” She saw clearly that the bicycle was motivating non-activists to take political action. They thought they were just having fun, but really were turning the culture upside down.

RW: What was one of the most surprising things you learned about the bicycle in your research?

MG: One of the coolest things I learned was about the Wright brothers. Everyone knows they were bicycle mechanics, but it always seemed to me a coincidence that bicycle mechanics invented the airplane. What I discovered by reading the work of historians like Tom Crouch, who wrote a great biography of the Wright brothers called The Bishop’s Boys, was that the bicycle gave the Wrights a crucial insight into how to keep an airplane aloft. Many inventors who were working on airplanes were trying to throw something in the air that would know how to go straight on its own. The Wright brothers went at it a different way. They realized that you don’t have to create a machine that knows on its own to go straight, because the pilots can be the brains of the machine. When you’re riding a bike, your body becomes one with the machine, and your sense of balance, and the unconscious corrections you make as you ride, are what balance the machine. The Wrights were able to take that same concept and put it in the air.

RW: Can you tell us more about the history of biking in America versus that of biking in Europe? Did bicycling affect other countries the same way it affected ours?

MG: Though a lot of developments were parallel, there were some interesting divergences. The main one came at the end of the 19th century. There had been a big 1890s bike boom in Europe as well as the U.S., but when that fad ended in the U.S., bike use really dropped off a cliff here. People without horses still rode them get to work or make deliveries, but they became absolutely unfashionable. Nobody rode them for fun. And this is years before the automobile became affordable for anyone other than the super rich. In order to keep the market for American bicycles going, bicycle manufacturers started targeting the youth market. They ended up making bicycles a childhood necessity, but they also made bikes seem like they were only for kids. As soon as you turned 16, you wouldn’t be caught dead on one, and no adult would ride one. That was very much an American phenomenon; it didn’t happen anywhere else as far as I’m aware, and it didn’t really start to turn around until the 1960s. There was a huge bike boom here in the 1970s, and by the 1980s, the United States started exporting styles, like the rugged mountain bike with straight handlebars that you could ride off-road. That was invented in the United States and caught on overseas.

RW: Would you say that biking in the U.S. today is as common as it is in Europe?

MG: It’s not, but in American cities, it can feel like it’s going in that direction. There are many more bike lanes than there were 10 years ago. There are many more people on bikes, including middle-aged people and young parents toting kids around. Where it’s safe to ride and people live near places they need to go, there is a mini-boom, though nationally, bike ridership is going down. Outside of the prosperous parts of cities, many people don’t live near their work, church, or shops, so bicycling is not practical for them. And in many parts of the country, roads are designed to allow cars to go as fast as possible, which makes them too dangerous for cyclists. And it’s no longer the case that every American kid has a bike, because a lot of kids don’t have a safe place to ride or don’t live close enough to the places they’d want to ride to.

RW: Are many people concerned about climate change biking to and from work?

MG: Riding your bike more is certainly one way you can reduce your carbon footprint. But it has to be practical for people. You have to get to work, you have to haul groceries, you have to get your kids to school. If you live in a place where it’s not possible to do those things on a bike or on foot or with public transit, you’re going to have to drive. Cities have a vested interest in making it easier for people to bicycle because bikes don’t pollute the air, they don’t cause wear and tear on the roads, they don’t create the same parking demands.

RW: Bikes are very popular on college campuses.

MG: Colleges are typically places where everything is closer together, so they’re easy to get around by bike. And most students who live on campus don’t have little kids that they need to provide transportation for, or jobs many miles away that they have to commute to. So bikes work well in that environment.

RW: If bicycles became a more popular form of transportation, where would they have the most impact? What would be the effect of more bicycles on the road?

MG: That’s hard to say, because there are changes coming to traffic that could make the roads much safer for bikes and pedestrians, or much less safe. We know that we’re going to have autonomous cars soon. But how are they going to behave? Will they be well programmed and well-regulated to make traffic calmer and more logical, and make it safer for bikes? Or will they be out there like bumper cars, clipping anything that gets in their way? If the roads do become safer for bikes, you’ll see more of them — studies show that the safer it is to ride, the more people ride.

MG: That’s hard to say, because there are changes coming to traffic that could make the roads much safer for bikes and pedestrians, or much less safe. We know that we’re going to have autonomous cars soon. But how are they going to behave? Will they be well programmed and well-regulated to make traffic calmer and more logical, and make it safer for bikes? Or will they be out there like bumper cars, clipping anything that gets in their way? If the roads do become safer for bikes, you’ll see more of them — studies show that the safer it is to ride, the more people ride.

RW: What are the most bike-friendly cities in the U.S.?

MG: Brooklyn is one of the centers of biking in the country. Also Portland, Oregon, is huge for biking. Seattle is really good for biking. I work in D.C., which has one of the highest bike-commuting rates in the country. We have laws that are very helpful, such a leading pedestrian indicator law that gives pedestrians and bikes a few extra seconds to cross the street, so that they clear the intersection before traffic starts moving. It makes everybody safer and makes traffic move better. Chicago is supposed to be great and also Minneapolis, which is amazing to me because it’s so cold up there. But you can bike all winter long, you just have to have the right gear.

One really exciting thing that’s happening all over the country is the rise of bike-share systems. You use your credit card to check out a bike, go where you’re going, and check it back in. That’s an amenity that can make biking accessible to people who can’t necessarily use a bike as their main form of transportation. In New York, for example, if you live in one of the outer boroughs, you can take the subway into Manhattan for work, but then use a bikeshare bike to go across town for lunch or something. Bikeshares are turning American cities into places where you can bike on a whim, where you might not have wanted to or been able to before.

RW: Do you ride your bike to work, and what kind of bicycle do you own?

MG: Yes, I ride a green 1999 Jamis Aurora touring bike. I love it. I ride an hour to work — it’s about half an hour on a woodsy rails-to-trails path — and then across town through traffic. By the time I get to my desk, I feel like a hero.

Read Margaret Guroff’s essay, “How Bikes Built Our Highways,” which appears in the January/February 2016 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

An Interview with David McCullough

David McCullough has been writing bestsellers for nearly 50 years, yet every new book is an adventure for him. Maybe that explains why he is widely acclaimed as a “master of the art of narrative history.” His books on such diverse subjects as George Washington, Harry Truman, and the Brooklyn Bridge have brought him a slew of awards, from the Pulitzer Prize to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Many of us also know him for his erudite narration of Ken Burns’ the Civil War series and Gary Ross’ movie Seabiscuit. But his greatest pride, McCullough tells me, is to be able to reach new generations with his writing. He reminds me that every single book he has published is still in print.

I expected a scholarly point of view from the man who brings American history to life for me, but I was as much taken with his youthful enthusiasm. In each of his books, there’s the grand picture and the details that allow readers to get inside the experience of the events and feel what it was like, but what makes his books so readable is what I’ll call the human factor, the reminder that our heroes are far from perfect.

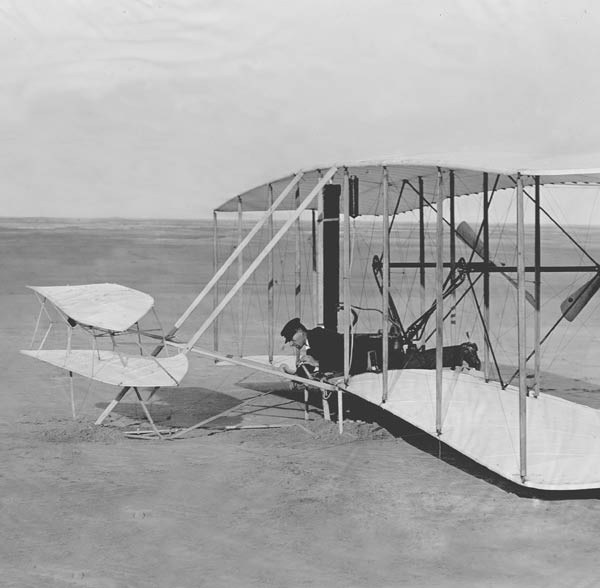

McCullough’s most recent bestseller, published earlier this year, is The Wright Brothers. He takes us on the journey with Wilbur and Orville as they pursue their crazy dream of making humans fly. We ride the triumphant first piloted flight in 1903 that took “four years … accidents, one disappointment after another, public indifference or ridicule, and clouds of demon mosquitoes.”

Like many of the other historical figures whose stories he has told, the Wright brothers had the determination to succeed in the face of long, seemingly impossible odds. What about McCullough himself? Where and when did he get his love of writing? Why is he so mesmerized by looking back through the years, and what does he think we are missing today that history could teach us all?

The Saturday Evening Post: If someone was planning to write the history of David McCullough, where should they start?

David McCullough: In Pittsburgh during my boyhood growing up at the time of the Second World War. The Sunday of the attack on Pearl Harbor came when I was at a concert hall in Pittsburgh where I’d gone with my older brother to see a ballet. I was only 8 years old, and I remember there was a crowd out on the street all looking very serious and talking intensely because the Japanese had attacked us. That was my first sense that there was a world beyond Pittsburgh.

SEP: What was your childhood like?

DM: I grew up in a wonderful neighborhood full of action. We’d play softball and street hockey on roller skates, and I had one of my teeth knocked out when I hit the curb one day. We raised hell at Halloween time, and that was a ball. The biggest difference between then and now is that we weren’t watched over much. We were free to go our own way, have our own adventures, make our own mistakes, get in trouble, and learn from it. At night, this is when the war was going on and the mills were going full blast, the skies would pulse red from the flash furnaces.

SEP: What influenced you to become a writer?

DM: I was one of four boys, and we gathered at the dinner table every night with my parents and sometimes my grandmother, and there were always stories being told. I think that storytelling is part of my DNA. My father, particularly, loved to tell stories and told them very well. He would talk about the famous floods and fires and strikes and the peculiar characters in our family — my favorite part of it. So in school whenever the teacher would ask if someone wanted to tell a story, my classmates seemed to always pick me, and the reason they did is because I told my stories in such a way that it took up the whole hour.

SEP : When you pick a subject for a book it’s a big commitment. When did you decide that the story of the Wright brothers was worth telling?

DM: I was researching my previous book The Greater Journey, which is about ambitious Americans who traveled to Paris in the 19th century to improve their skills in medicine and architecture and art. Along the way, I was astonished to discover Wilbur and Orville Wright and their sister, Katharine. I knew they were bicycle mechanics and flew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. I knew as much as what all of us learned in 10 minutes in high school. I found out Wilbur had a very strong interest in art and architecture. The brothers were extremely well-self-educated people with a lot of curiosity about many subjects. The more I read about them, the more I realized that this would make a terrific book, particularly the human side of their story, not just the aeronautical accomplishments.

SEP: It’s usually just Orville and Wilbur. Until your book, not many of us were aware of Katharine’s role in their story.

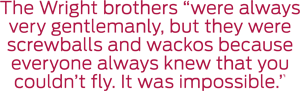

DM: The brothers were very reluctant to be public figures, particularly Orville, who was quite shy. But Katharine loved being interviewed by the press and being the center of attention. She was a powerhouse, only about 5-foot-1, and with her gold-rimmed glasses and her hair tied back in a bun, she could be mistaken for the typical schoolmarm of the day, but she was much more than that. She was full of beans and opinionated and energetic and had a temper but was always there when they needed her. As for the brothers, they were always very gentlemanly, but they were screwballs and wackos because everyone always knew that you couldn’t fly. It was impossible. When the brothers offered to bring their flying machine to Washington to demonstrate, they got the door slammed in their faces four times.

SEP: I get a feeling that you’re attracted to them and some of the other people you’ve written about because they fought against the odds.

DM: Absolutely. They would not give up. Look what George Washington faced in the year 1776. Everything was going wrong. There was not a chance that they would win that war, but he never gave up. Look at Harry Truman in 1948, everybody knew perfectly well that he didn’t have a chance to get elected president, but he wouldn’t give up. That’s an admirable quality and one that we need to instill in our young people. When you get knocked down, don’t lie there and whimper and blame other people. Get up, get back on your feet, keep going, and learn from what went wrong — learn from your mistakes. Failure is part of life. Setbacks are inevitable. The Wright brothers figured it all out and did it all on their own, and there’s so much to be learned from that. They were very smart engineers and ingenious builders, but every time they went up in one of their test flights, each of them knew that he was running a very big risk of being killed.

Photo by Orville Wright/Library of Congress

SEP: You’ve been writing for five decades, book after book, does it come easy to you?

DM: I don’t think most people know how hard it is to write a book. I think they’ve got this image of writers as sort of sitting down and tossing it off for two or three hours before lunch and then taking a walk or whatever. It isn’t that way. I work every day, all day, and happily. I am never happier than when I’m working. I think that writing focuses the mind in a way that nothing else does. You find yourself having a thought, an insight, an idea that you would have never had if you weren’t writing. That can be quite exciting. I’ve never undertaken a book where I didn’t find something new — something nobody knew until then. It’s very exciting. That’s like finding treasure.

I have a saying that I had a calligrapher do for me, and it’s framed on the mantelpiece of the room where I work. It’s from the English author Jonathan Swift, written in 1738, that says, “May you live all the days of your life.” It’s that simple. I feel that life is given a lift through the love of learning, and each of my books has been, for me, a powerful learning experience — an adventure. I’ve never undertaken a book about a subject that I knew a lot about because if I knew all about it, I wouldn’t want to write the book. It’s the discovery, the hunt, the process, setting foot on a continent you’ve never been to before — a real lesson in not just history but life. Each one of them has been that for me.

SEP: We all sort of spout the cliché about history repeating itself and learning from the past. Do you believe that, and are we as a whole losing a sense of history because we’re in such an instant-news environment?

DM: Well, that’s part of it, but we’re also not teaching history as well or as much as we should. Eighty percent of the colleges and universities in this country — 80 percent — no longer require a course in history to graduate. That’s a very serious mistake. We learn from those people who went before, and we owe so much to them that to have no interest in them is a terribly gross expression of ingratitude. How much we have that we didn’t bring about — it was just handed to us — that those who went before us strived, worked, often struggled and died to make possible. We talk about how much we love our country, and we’re great patriots, but how can you love your country and take no interest in your country’s story? Why limit your knowledge and experience of life to the relatively brief time allotted by our lifetimes when the whole reach of the human experience going back thousands of years is open to us through the medium of history?

SEP: So, how do we change things?

DM: There’s no trick to getting people interested in history. Tell stories. We can’t begin too soon. It should begin in grade school and be heavily emphasized all the way through high school and college.

SEP: A lot of people say they’re disappointed in our leaders today. Do you think part of the problem is that our leaders have lost historical perspective?

DM: Yes, I do. I feel, in part, it’s because so many of the people that represent our interests in Congress and government have no sense of history or very little. Not much is accomplished alone. It’s a joint effort. That’s exactly what Congress has forgotten. You have to make it a joint effort and both sides have to work together to achieve things that are essential. You have to have knowledge of how you got to where you are in order to have some reasonable idea about where we should be headed.

More in the Post archive on the inventors and innovators of aviation:

“Thus Man Learned to Fly”

by Howard Mingos