David McCullough has been writing bestsellers for nearly 50 years, yet every new book is an adventure for him. Maybe that explains why he is widely acclaimed as a “master of the art of narrative history.” His books on such diverse subjects as George Washington, Harry Truman, and the Brooklyn Bridge have brought him a slew of awards, from the Pulitzer Prize to the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Many of us also know him for his erudite narration of Ken Burns’ the Civil War series and Gary Ross’ movie Seabiscuit. But his greatest pride, McCullough tells me, is to be able to reach new generations with his writing. He reminds me that every single book he has published is still in print.

I expected a scholarly point of view from the man who brings American history to life for me, but I was as much taken with his youthful enthusiasm. In each of his books, there’s the grand picture and the details that allow readers to get inside the experience of the events and feel what it was like, but what makes his books so readable is what I’ll call the human factor, the reminder that our heroes are far from perfect.

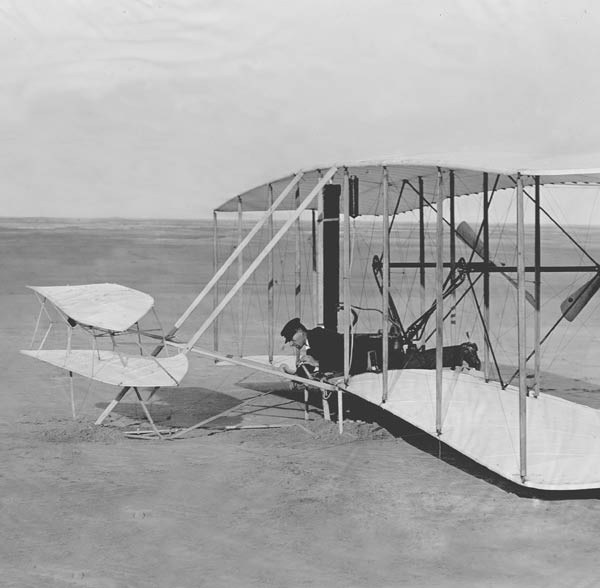

McCullough’s most recent bestseller, published earlier this year, is The Wright Brothers. He takes us on the journey with Wilbur and Orville as they pursue their crazy dream of making humans fly. We ride the triumphant first piloted flight in 1903 that took “four years … accidents, one disappointment after another, public indifference or ridicule, and clouds of demon mosquitoes.”

Like many of the other historical figures whose stories he has told, the Wright brothers had the determination to succeed in the face of long, seemingly impossible odds. What about McCullough himself? Where and when did he get his love of writing? Why is he so mesmerized by looking back through the years, and what does he think we are missing today that history could teach us all?

The Saturday Evening Post: If someone was planning to write the history of David McCullough, where should they start?

David McCullough: In Pittsburgh during my boyhood growing up at the time of the Second World War. The Sunday of the attack on Pearl Harbor came when I was at a concert hall in Pittsburgh where I’d gone with my older brother to see a ballet. I was only 8 years old, and I remember there was a crowd out on the street all looking very serious and talking intensely because the Japanese had attacked us. That was my first sense that there was a world beyond Pittsburgh.

SEP: What was your childhood like?

DM: I grew up in a wonderful neighborhood full of action. We’d play softball and street hockey on roller skates, and I had one of my teeth knocked out when I hit the curb one day. We raised hell at Halloween time, and that was a ball. The biggest difference between then and now is that we weren’t watched over much. We were free to go our own way, have our own adventures, make our own mistakes, get in trouble, and learn from it. At night, this is when the war was going on and the mills were going full blast, the skies would pulse red from the flash furnaces.

SEP: What influenced you to become a writer?

DM: I was one of four boys, and we gathered at the dinner table every night with my parents and sometimes my grandmother, and there were always stories being told. I think that storytelling is part of my DNA. My father, particularly, loved to tell stories and told them very well. He would talk about the famous floods and fires and strikes and the peculiar characters in our family — my favorite part of it. So in school whenever the teacher would ask if someone wanted to tell a story, my classmates seemed to always pick me, and the reason they did is because I told my stories in such a way that it took up the whole hour.

SEP : When you pick a subject for a book it’s a big commitment. When did you decide that the story of the Wright brothers was worth telling?

DM: I was researching my previous book The Greater Journey, which is about ambitious Americans who traveled to Paris in the 19th century to improve their skills in medicine and architecture and art. Along the way, I was astonished to discover Wilbur and Orville Wright and their sister, Katharine. I knew they were bicycle mechanics and flew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. I knew as much as what all of us learned in 10 minutes in high school. I found out Wilbur had a very strong interest in art and architecture. The brothers were extremely well-self-educated people with a lot of curiosity about many subjects. The more I read about them, the more I realized that this would make a terrific book, particularly the human side of their story, not just the aeronautical accomplishments.

SEP: It’s usually just Orville and Wilbur. Until your book, not many of us were aware of Katharine’s role in their story.

DM: The brothers were very reluctant to be public figures, particularly Orville, who was quite shy. But Katharine loved being interviewed by the press and being the center of attention. She was a powerhouse, only about 5-foot-1, and with her gold-rimmed glasses and her hair tied back in a bun, she could be mistaken for the typical schoolmarm of the day, but she was much more than that. She was full of beans and opinionated and energetic and had a temper but was always there when they needed her. As for the brothers, they were always very gentlemanly, but they were screwballs and wackos because everyone always knew that you couldn’t fly. It was impossible. When the brothers offered to bring their flying machine to Washington to demonstrate, they got the door slammed in their faces four times.

SEP: I get a feeling that you’re attracted to them and some of the other people you’ve written about because they fought against the odds.

DM: Absolutely. They would not give up. Look what George Washington faced in the year 1776. Everything was going wrong. There was not a chance that they would win that war, but he never gave up. Look at Harry Truman in 1948, everybody knew perfectly well that he didn’t have a chance to get elected president, but he wouldn’t give up. That’s an admirable quality and one that we need to instill in our young people. When you get knocked down, don’t lie there and whimper and blame other people. Get up, get back on your feet, keep going, and learn from what went wrong — learn from your mistakes. Failure is part of life. Setbacks are inevitable. The Wright brothers figured it all out and did it all on their own, and there’s so much to be learned from that. They were very smart engineers and ingenious builders, but every time they went up in one of their test flights, each of them knew that he was running a very big risk of being killed.

Photo by Orville Wright/Library of Congress

SEP: You’ve been writing for five decades, book after book, does it come easy to you?

DM: I don’t think most people know how hard it is to write a book. I think they’ve got this image of writers as sort of sitting down and tossing it off for two or three hours before lunch and then taking a walk or whatever. It isn’t that way. I work every day, all day, and happily. I am never happier than when I’m working. I think that writing focuses the mind in a way that nothing else does. You find yourself having a thought, an insight, an idea that you would have never had if you weren’t writing. That can be quite exciting. I’ve never undertaken a book where I didn’t find something new — something nobody knew until then. It’s very exciting. That’s like finding treasure.

I have a saying that I had a calligrapher do for me, and it’s framed on the mantelpiece of the room where I work. It’s from the English author Jonathan Swift, written in 1738, that says, “May you live all the days of your life.” It’s that simple. I feel that life is given a lift through the love of learning, and each of my books has been, for me, a powerful learning experience — an adventure. I’ve never undertaken a book about a subject that I knew a lot about because if I knew all about it, I wouldn’t want to write the book. It’s the discovery, the hunt, the process, setting foot on a continent you’ve never been to before — a real lesson in not just history but life. Each one of them has been that for me.

SEP: We all sort of spout the cliché about history repeating itself and learning from the past. Do you believe that, and are we as a whole losing a sense of history because we’re in such an instant-news environment?

DM: Well, that’s part of it, but we’re also not teaching history as well or as much as we should. Eighty percent of the colleges and universities in this country — 80 percent — no longer require a course in history to graduate. That’s a very serious mistake. We learn from those people who went before, and we owe so much to them that to have no interest in them is a terribly gross expression of ingratitude. How much we have that we didn’t bring about — it was just handed to us — that those who went before us strived, worked, often struggled and died to make possible. We talk about how much we love our country, and we’re great patriots, but how can you love your country and take no interest in your country’s story? Why limit your knowledge and experience of life to the relatively brief time allotted by our lifetimes when the whole reach of the human experience going back thousands of years is open to us through the medium of history?

SEP: So, how do we change things?

DM: There’s no trick to getting people interested in history. Tell stories. We can’t begin too soon. It should begin in grade school and be heavily emphasized all the way through high school and college.

SEP: A lot of people say they’re disappointed in our leaders today. Do you think part of the problem is that our leaders have lost historical perspective?

DM: Yes, I do. I feel, in part, it’s because so many of the people that represent our interests in Congress and government have no sense of history or very little. Not much is accomplished alone. It’s a joint effort. That’s exactly what Congress has forgotten. You have to make it a joint effort and both sides have to work together to achieve things that are essential. You have to have knowledge of how you got to where you are in order to have some reasonable idea about where we should be headed.

More in the Post archive on the inventors and innovators of aviation:

“Thus Man Learned to Fly”

by Howard Mingos

“I Flew Around the World Alone”

by Joan Merriam

“And Then I Jumped”

by Charles A. Lindbergh

“Lindbergh Four Years After”

by Donald E. Keyhoe

“The First Birdman”

by J.W. Mitchell

“Earnings of Aviators”

by John Mitchell

“The Making of an Aviator”

by Harry N. Atwood

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now