Is 100-Year-Old Wisdom Still Relevant?

“When a father gives his son good advice, he is probably as wise as the sages of old,” Edgar Watson Howe wrote in this magazine 100 years ago. “Few children go astray as the result of taking the advice of a father or mother.”

And yet: “I don’t know which is the more objectionable, an old man’s conceit because of his wisdom, or a young man’s because of his youth.” What Howe’s aphorisms may have lacked in consistency, they made up for in volume.

If your grandparents or great-grandparents lived in the U.S. a century ago and displayed an indestructible ethic for thrift and hard work coupled with animosity for shiftlessness, they might have absorbed the work of the prolific and quotable Howe.

Like a lot of “crackerbox philosophers” of his time, Howe assembled humorous columns and stories from the folksy lessons of his rural Midwestern life. He wrote about the peculiar inhabitants of middle America’s small towns in his “nonfiction novels” like The Anthology of Another Town, and he gave regular opinion and advice in his nationally-circulating E.W. Howe’s Monthly, “devoted to indignation and information.” Although Howe has been functionally wiped from the American consciousness, his sage quips were all the rage in the early 20th century, reprinted in papers from coast to coast regularly. Mark Twain praised Howe’s unique depictions of small-town life, writing, “you may have caught the only fish there was in your pond.”

“Millions of men have lived millions of years and tried everything,” Howe wrote. “Anyone who bets on his judgment against the judgment of the world will be punished for folly.” But his own judgment met plenty of skepticism.

In Howe’s writings for The Saturday Evening Post, he replicated his “common sense” approach to life that praised grit and persistence and pitied his lazier peers who just couldn’t see that “success is easier than failure.” His hard-knock ethical code wasn’t roundly received as scripture. Howe’s critics pointed to the Panic of 1893, widespread poverty among hard-working immigrants, and the inescapable hardships of the Great Depression as proof that reality was antithetical to his fixation on self-reliance.

Howe insisted that the old sentimental story of the poor man jailed for stealing bread for his starving family was pure fiction, that any such criminal would be met with a system ready to “relieve his distress” instead of persecuting him. Writing in The Nation in 1934, critic Ernest Boyd claimed the “fundamental falsity” of Howe’s ideas “has been obvious to every thinking person since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, at least.”

After his death, in 1941, Howe’s son wrote about him in a Post article titled “My Father Was the Most Wretchedly Unhappy Man I Ever Knew.” Gene Howe confessed that he had been terrified of his father’s wrath his entire life, describing the elder Howe’s rigid positions against women and religion. “I do not believe there ever lived a writer who could hurt as he did,” Gene Howe wrote, “who was so blunt and direct, and who could lacerate so deeply. I know he did not realize this himself.”

Still, Howe’s son contended that his father operated with the sole purpose of saving humanity from itself by publicizing far and wide the “virtue of selfishness.”

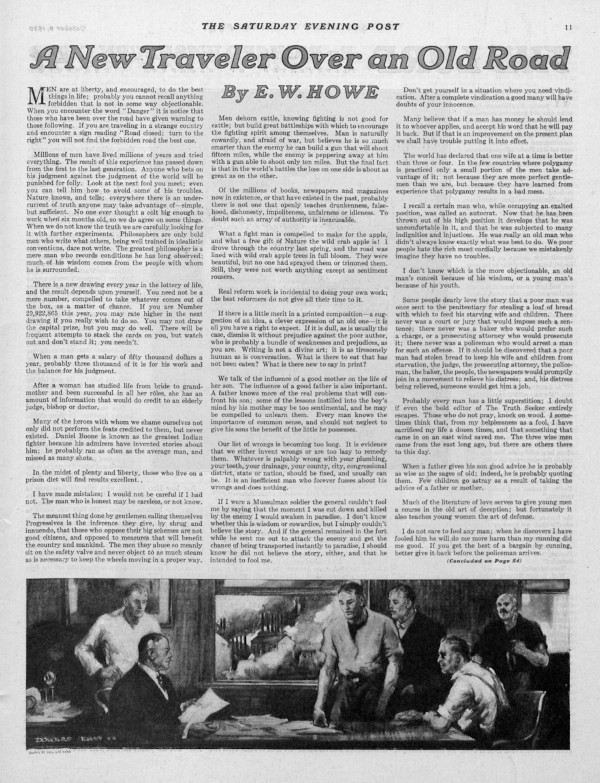

E.W. Howe’s essay “A New Traveler Over an Old Road,” printed 100 years ago in the Post, offers glimpses of a controversial thinker’s “accumulated wisdom”:

- “The devil is dead; but he never took so much interest in your misconduct as your neighbors did. And the neighbors are still here to watch you.”

- “Our list of wrongs is becoming too long. It is evidence that we either invent wrongs or are too lazy to remedy them. Whatever is palpably wrong with your plumbing, your teeth, your drainage, your county, city, congressional district, state or nation, should be fixed, and usually can be. It is an inefficient man who forever fusses about his wrongs and does nothing.”

- “If there is a little merit in a printed composition — a suggestion of an idea, a clever expression of an old one — it is all you have a right to expect. If it is dull, as is usually the case, dismiss it without prejudice against the poor author, who is probably a bundle of weaknesses and prejudices, as you are. Writing is not a divine art; it is as tiresomely human as is conversation. What is there to eat that has not been eaten? What is there new to say in print?”

- “Don’t get yourself in a situation where you need vindication. After a complete vindication a good many will have doubts of your innocence.”

- “Probably every man has a little superstition; I doubt if even the bold editor of The Truth Seeker entirely escapes. Those who do not pray, knock on wood. I sometimes think that, from my helplessness as a fool, I have sacrificed my life a dozen times, and that something that came in on an east wind saved me. The three wise men came from the east long ago, but there are others there to this day.”

- “I do not care to fool any man; when he discovers I have fooled him he will do me more harm than my cunning did me good. If you get the best of a bargain by cunning, better give it back before the policeman arrives.”

- “Exaggerating the rewards of virtue is in bad taste. A man may practice all the virtues and not be notably prosperous or happy; but he will get along better than the idle or unscrupulous. A good man will have pains and difficulties as surely as the wicked man, but he will have fewer of them. This is about all that may be truthfully said in favor of virtue.”

- “A new idea is not enough; it must be a good idea also. I have no wish to write a well-rounded or eloquent sentence that will cause anyone to believe that which is untrue or unfair.”

Featured image: “The Philosopher of Potato Hill,” 1905-1910, The Kansas Historical Society

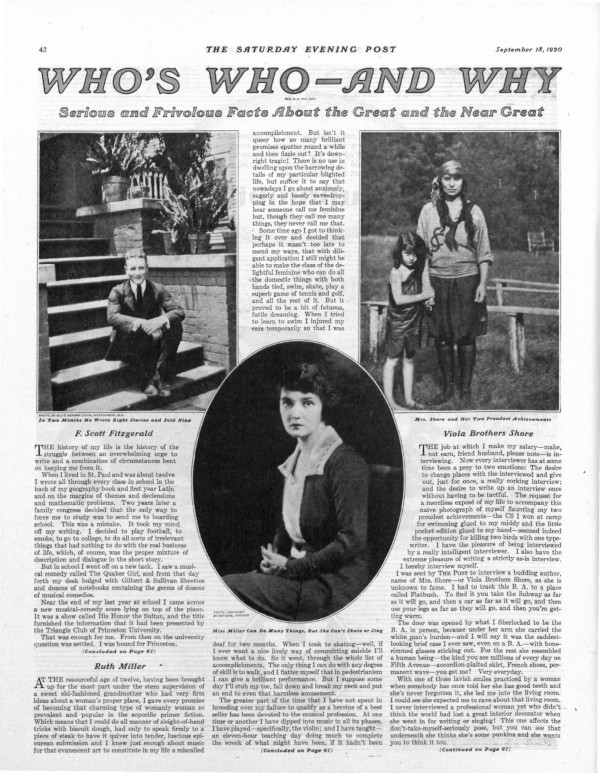

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Rocky Start in Writing

Amidst the gleam of his emerging career, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote a short personal essay for the Post’s “Who’s Who — and Why?” section letting the magazine’s readers in on where this new writer had come from. The year, 1920, had been a momentous one for Fitzgerald, having published his first novel, This Side of Paradise, along with several short stories: first, “Head and Shoulders,” and “The Ice Palace,” and later the famous “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The “jazz age” author offers distant comments on his life hitherto as though it were all an ironic dream leading him to inevitable success. Fitzgerald would muse about his own life for the magazine many more times in the years to come, penning “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” in 1924 and “One Hundred False Starts” in 1933.

Originally Published on September 18, 1920

The history of my life is the history of the struggle between an overwhelming urge to write and a combination of circumstances bent on keeping me from it.

When I lived in St. Paul and was about twelve I wrote all through every class in school in the back of my geography book and first year Latin and on the margins of themes and declensions and mathematic problems. Two years later a family congress decided that the only way to force me to study was to send me to boarding school. This was a mistake. It took my mind off my writing. I decided to play football, to smoke, to go to college, to do all sorts of irrelevant things that had nothing to do with the real business of life, which, of course, was the proper mixture of description and dialogue in the short story.

But in school I went off on a new tack. I saw a musical comedy called The Quaker Girl, and from that day forth my desk bulged with Gilbert & Sullivan librettos and dozens of notebooks containing the germs of dozens of musical comedies.

Near the end of my last year at school I came across a new musical comedy score lying on top of the piano. It was a show called His Honor the Sultan, and the title furnished the information that it had been presented by the Triangle Club of Princeton University.

That was enough for me. From then on the university question was settled. I was bound for Princeton.

I spent my entire Freshman year writing an operetta for the Triangle Club. To do this I failed in algebra, trigonometry, coordinate geometry, and hygiene. But the Triangle Club accepted my show, and by tutoring all through a stuffy August I managed to come back a Sophomore and act in it as a chorus girl. A little after this came a hiatus. My health broke down and I left college one December to spend the rest of the year recuperating in the West. Almost my final memory before I left was of writing a last lyric on that year’s Triangle production while in bed in the infirmary with a high fever.

The next year, 1916-17, found me back in college, but by this time I had decided that poetry was the only thing worthwhile, so with my head ringing with the meters of Swinburne and the matters of Rupert Brooke I spent the spring doing sonnets, ballads and rondels into the small hours. I had read somewhere that every great poet had written great poetry before he was 21. I had only a year and, besides, war was impending. I must publish a book of startling verse before I was engulfed.

By autumn I was in an infantry officers’ training camp at Fort Leavenworth, with poetry in the discard and a brand new ambition—I was writing an immortal novel. Every evening, concealing my pad behind Small Problems for Infantry, I wrote paragraph after paragraph on a somewhat edited history of me and my imagination. The outline of 22 chapters, four of them in verse, was made, two chapters were completed; and then I was detected and the game was up. I could write no more during study period.

This was a distinct complication. I had only three months to live — in those days all infantry officers thought they had only three months to live — and I had left no mark on the world. But such consuming ambition was not to be thwarted by a mere war. Every Saturday at one o’clock when the week’s work was over I hurried to the Officers’ Club, and there, in a corner of a roomful of smoke, conversation and rattling newspapers, I wrote a one-hundred-and-twenty-thousand-word novel on the consecutive weekends of three months. There was no revising; there was no time for it. As I finished each chapter I sent it to a typist in Princeton.

Meanwhile I lived in its smeary pencil pages. The drills, marches and Small Problems for Infantry were a shadowy dream. My whole heart was concentrated upon my book.

I went to my regiment happy. I had written a novel. The war could now go on. I forgot paragraphs and pentameters, similes and syllogisms. I got to be a first lieutenant, got my orders overseas — and then the publishers wrote me that though The Romantic Egotist was the most original manuscript they had received for years they couldn’t publish it. It was crude and reached no conclusion.

It was six months after this that I arrived in New York and presented my card to the office boys of seven city editors asking to be taken on as a reporter. I had just turned 22, the war was over, and I was going to trail murderers by day and do short stories by night. But the newspapers didn’t need me. They sent their office boys out to tell me they didn’t need me. They decided definitely and irrevocably by the sound of my name on a calling card that I was absolutely unfitted to be a reporter.

Instead I became an advertising man at 90 dollars a month, writing the slogans that while away the weary hours in rural trolley cars. After hours I wrote stories — from March to June. There were 19 altogether; the quickest written in an hour and a half, the slowest in three days. No one bought them, no one sent personal letters. I had 122 rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room. I wrote movies. I wrote song lyrics. I wrote complicated advertising schemes. I wrote poems. I wrote sketches. I wrote jokes. Near the end of June I sold one story for 30 dollars.

On the Fourth of July, utterly disgusted with myself and all the editors, I went home to St. Paul and informed family and friends that I had given up my position and had come home to write a novel. They nodded politely, changed the subject and spoke of me very gently. But this time I knew what I was doing. I had a novel to write at last, and all through two hot months I wrote and revised and compiled and boiled down. On September 15th This Side of Paradise was accepted by special delivery.

In the next two months I wrote eight stories and sold nine. The ninth was accepted by the same magazine that had rejected it four months before. Then, in November, I sold my first story to the editors of The Saturday Evening Post. By February I had sold them half a dozen. Then my novel came out. Then I got married. Now I spend my time wondering how it all happened.

In the words of the immortal Julius Caesar: “That’s all there is; there isn’t anymore.”

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, September 18, 1920

The Late, Great Robert K. Massie Wrote About American Life

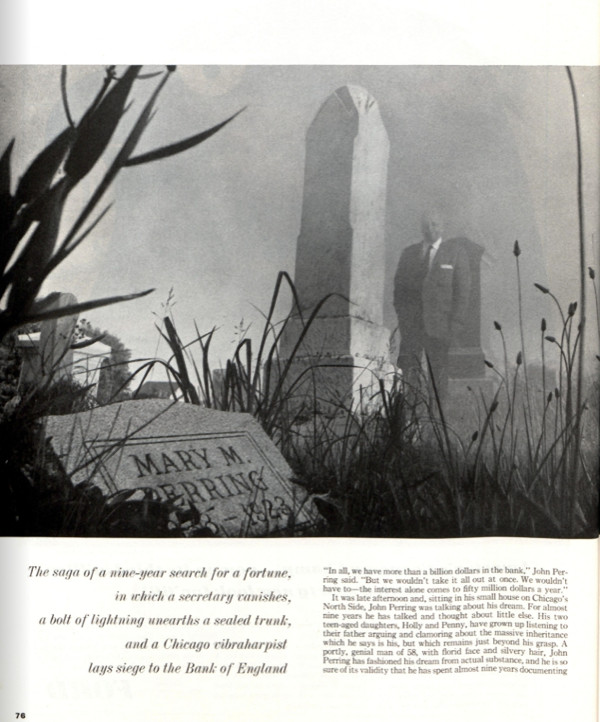

Journalist and historian Robert K. Massie passed away last Monday, December 2nd at 90 years old. Massie was a contributing editor for The Saturday Evening Post throughout the ’60s, writing about international trade, racial integration, and American life. After leaving the Post, Massie focused more on history, and he published biographies of Russian rulers and histories of warships. His book Peter the Great: His Life and World won the Pulitzer Prize in 1981.

Massie’s feature stories in this magazine spanned a wealth of topics, from gray wolves to Teddy Kennedy to Harlem housing activists. In 1965, Massie followed around a Chicago musician named John Perring who also happened to be fighting the Bank of England for an inheritance he claimed to be more than a billion dollars. Perring’s ancestors had been wealthy merchants, as evidenced by old tax documents he unearthed in Michigan, and several twists and turns during his investigation posed new questions about his supposed inheritance. The story, “Please Send One Billion Dollars,” chronicled Perring’s bizarre, fruitless treasure hunt with thoroughness and detailed storytelling signature to Massie’s work.

Headlines from Robert K. Massie articles that appeared in the Post (©SEPS)

Adventures in the Kindle Trade

Six months after Maurice Sendak died in May 2012, The Believer published an interview British journalist Emma Brockes had done with him. She asked him his opinion of e-books. “I hate them,” Sendak responded. “It’s like making believe there’s another kind of sex. There isn’t another kind of sex. … Even as a kid, my sister, who was the eldest, brought books home for me, and I think I spent more time sniffing and touching them than reading. I just remember the joy of the book, the beauty of the binding.” [Read the related article “A War on Writers?” by Steven Slon from the Jan/Feb 2015 issue.]

I know the feeling. I too grew up holding, fondling, and smelling books. When I got older I began collecting them. I’ve spent hundreds, probably thousands, of hours hunting down books of writers I’ve gotten to know. When I began writing books of my own, there was such a thrill to see them in print. I will never forget walking past the Madison Avenue Bookstore in Manhattan the week my Conversations with Capote was published in the winter of 1985. It was my first book. And there it was. It was, to say the least, a very special, very personal moment.

My books — my own, and all the others I’ve collected — mean a great deal to me. But I no longer hold the opinion Mr. Sendak did. I don’t hate e-books. I can’t, because my last seven books have been — I hate to admit — e-books.

When Ann Patchett, best-selling author of Bel Canto and State of Wonder, and the owner of an independent bookstore in Nashville, Tennessee, was asked her opinion of e-books, she said, “I care that you read, not how you read.”

I care too. I care very much. The 11 books I am currently reading weigh 19.5 pounds; in my Kindle they weigh zero — that alone makes a good case for e-reading.

“The recent contractions and consolidations in the publishing business — layoffs, dwindling sales and advances, mergers of houses once thought unassailable — have left a widespread sense of unease about the durability of books,” Giles Harvey wrote in a recent New Yorker article about why failed novelists turn to writing memoirs about their failures. “Reading in bed with his girlfriend, novelist Benjamin Anastas wonders if the rise of e-books ‘will help keep writing alive and well into the digitized future, or if my problems are an early warning that my profession is about to go extinct.’”

I don’t think books will go extinct. More precisely, it’s become a changing art. According to the book research firm Bowker, self-publishing now accounts for more than 458,564 books annually, with Amazon leading the way. E-books cannot be ignored. The new problem is how to separate the good from the bad and the ugly.

In the April 2013 Wired, Evan Hughes wrote, “After centuries in which books and the process of publishing them barely changed, the digital revolution has thrown the entire business up for grabs. It’s a transformation that began with the rise of Amazon as an online bookseller and accelerated with the resulting decline of the physical bookstore. But with the shift to e-books — which now represent upwards of 20 percent of big publishers’ revenue, up from 1 percent in 2008 — every aspect of the existing framework is now open to debate: how much books will cost, how long they’ll be. … The only certainty is that the venerable book business, a settled landscape for so long, is now open territory for anyone to claim.”

Adam Gopnik, writing in The New Yorker, expressed a similar sentiment. “Thanks to the Internet, the disproportion between writerly supply and demand, always tricky, has tipped: Anyone can write, and everyone does, and beginners are expected to be the last pure philanthropists, giving it all away for the naches. It has never been easier to be a writer; and it has never been harder to be a professional writer.”

It has always been hard to be a professional writer. And yes, it’s a lot harder today. When I started writing books, I received an advance from a publisher that allowed me enough time to write the book. It was never a great deal of money — I got $50,000 for the first book, and $215,000 was the most I ever got, but that book (The Hustons) took me three years to write. Thankfully I was able to supplement my income by writing for magazines, until that world began to shrink as well. So the challenge is to continue being a professional writer — i.e., a writer who makes a living from his writing — in an e-book, self-publishing world. That was the quandary for most of the writers I knew. The only way to find out was to jump in. If I wanted to write what I wanted to write — novels, satire, poetry, memoirs — I would have to test the waters by sticking my own feet in them. I made an investment in myself. And a deal with Amazon. Would it turn out to be a deal with the devil? Or with my savior?

I’m not alone. Name writers like Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, and David Mamet have all put out e-book originals. But, as Bruce Miller, president of Miller Trade Book Marketing warned, “Celebrity authors may have great luck self-publishing, but most authors are not famous.”

Amazon has added a new twist to this market by hiring an editor, David Blum, who carefully selects Amazon Singles, original works of 5,000 to 30,000 words of both nonfiction and fiction. He gets more than 1,000 submissions a month and has published 345 Singles in the first two years of the program. Approximately one-third of these have sold at least 10,000 copies, at an average of $2 per Single. As the writer gets 70 percent of this, it’s understandable why so many are trying to make the cut.

But the truth is, with every successful e-book writer’s story, there are hundreds of thousands of failures. “There are so many stories out there about people who have made it big self-publishing,” literary publicist Julia Drake told Publishers Weekly Select, a magazine devoted to self-publishing, “and there’s not enough out there about the 99 percent of the authors who’ve self-published a book and it disappears.” The only reality each writer faces is his own.

My first step was to spend $350 to digitize the four books of mine whose rights had been returned to me: Conversations with Capote, The Hustons, Conversations with Michener, Above the Line, and Conversations with Brando. Then I found out about Amazon’s White Glove Program, a program for established writers. If invited in, Amazon will take care of the business of digitizing your books and will work with you to get them ready for self-publication, pending your approval. I was invited to join that program. And then they told me about their Select program, where I would be “allowed” to offer any of my books for free to their readers for up to five days over three months. Why would I do that? I wondered. To raise my profile, I was told. The higher one’s profile, the better chance of gaining new readers. Freebies were designed to create word-of-mouth sales. And since I had more than one book, if a reader took one of my books for free, they might be encouraged to buy the others. Besides the four previously published books, I had seven others I was working on. My Amazon contact thought it would be a smart idea to release them all at the same time. Instead of putting out one book and waiting, I could put out all 11 books, so when someone went to my book page they could see all of them at once. But I was still some distance away from publishing. Before I could digitize them I needed my trusty copy editor to go over each and every paragraph. Once she was done, I needed to place the photos I wanted to include, to get permission to use illustrations and quotes, and to get each book cover designed. Once everything was in order, I gave the books to Amazon. When they said they were ready, I went over each of them and found problems that had to be fixed. That back and forth took a few more months. When it came time to click publish and see these books go public, I next had to think about how to market them. Because so many books go out into the electronic world each day, I was really just getting started. And this was the worst part of the process, because it meant letting all the people I knew, through email, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, that these books were now available.

This was now my welcome to the real world of social networking. The world where all your friends, and “friends,” and former students send congratulations and encouragement and then go on with their busy lives. In other words, ignoring your pleas to buy your books. That’s when you begin to see the genius in Amazon’s free books idea. If they won’t purchase, then you can give them a taste, select one of the books, and nudge them to buy the others. So, I put up Capote first, and lo and behold, 2,000 people took it the first day. When sales of the other books remained meager, I offered them Brando for free. One thousand took that one. When no one was buying either of the novels, I put one up one month, the other the next. Four hundred people took them. Yoga? No! Shmoga!, my satire on yoga? I could barely give it away. How do I know how many people are buying, borrowing, or taking them for free? Because I can go to my reports on Amazon and check the month-to-date unit sales. Whereas before I had to wait six months to find out how any of my books were selling, now it is instant.

The first month, I earned over $600. The second, around $400. The third, under $200. It’s not exactly what I was selling in print. The Hustons had a 50,000 print run and supposedly sold 80 percent of those; I don’t have the figures of all the other books, but I do know that each of them sold at least in the four or five figures.

Stephen Marche, in Esquire, has pooh-poohed writers who whine about the terrible state of publishing today. He points out that “for writers starting out, there are more options, more means of access to the marketplace, than ever before.” And he quotes two pollsters (Gallup and Pew) who claim that the number of books the average American reads per year is 17. He says we’re in “the golden age for writers and writing.”

I agree that there are more options for writers today, but what Marche neglects to address is how many of these options allow a writer to actually earn a living from his writing. He points to how J.K. Rowling is richer than the queen of England and that Tom Wolfe got $7 million for his last novel, but there will always be writers who hit the literary lottery. It’s all the others in the game that Marche dismisses by saying “Everyone seems to understand and accept this golden age except the writers themselves.” Well, yes, the writers in the trenches. They don’t quite understand and accept. As for the average American reading 17 books a year? You’ve got to be kidding me. I know a lot of educated people. Very few of them read 17 books a year. Most people I know just read occasionally and watch a lot of TV. They can reference Mad Men, Game of Thrones, Seinfeld episodes, and Downton Abbey. But ask them what they thought of The Gravedigger’s Daughter or The Emperor of All Maladies and see if their eyes cross.

“It does seem a bit high,” said Joyce Carol Oates when I asked her what she thought about it. Oates is the only writer I know who can write 17 books a year. “Maybe these are self-help books and cookbooks,” she mulled.

Having taught gifted English majors at UCLA for 10 years, I’m pretty convinced that even they didn’t read much more than what they were assigned. It may be far easier for all of them, and for anyone else, to self-publish these days, but getting people to actually read these things? That’s a whole other story.