In this 1929 interview with a Post reporter, Albert Einstein discussed the role of relativity, why he thought nationalism was the “measles of mankind,” and how he might have become a happy, mediocre fiddler if he hadn’t become a genius in physics.

When a Post correspondent interviewed Albert Einstein about his thought process in 1929, Einstein did not speak of careful reasoning and calculations. Instead —

“I believe in intuitions and inspirations. I sometimes feel that I am right. I do not know that I am… [but] I would have been surprised if I had been wrong

“I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

Something else that was circling the globe in that year was Einstein’s reputation. At the time of this interview, his fame had spread across Europe and America. Everywhere he was acclaimed a genius for defining the principles of relativity, though very few people understood what they meant.

Imagination may have been essential to his breakthrough thinking, but Einstein’s discovery also rested on his vast knowledge of physical science. Knowledge and imagination let him see the relationship between space, time, and energy. Using mathematics, he developed a model for understanding how objects and light behave in extreme conditions — as in the subatomic world, where the old Newtonian principles didn’t appear to work.

Whenever Einstein explained his work to the popular press, though, reporters got lost in his talk of space-time continuum, absolute speed of light, and E=Δmc2. So they used their own imaginations to define relativity. One of their misinterpretations was the idea that relativity meant everything is relative. The old absolutes were gone. Nothing was certain anymore.

It was a ridiculous interpretation that could only have made sense if newspaper readers were no bigger than a proton, or could travel near the speed of light.

This misperception was so common that the Post writer used it to start his interview.

“Relativity! What word is more symbolic of the age? We have ceased to be positive of anything. We look upon all things in the light of relativity. Relativity has become the plaything of the parlor philosopher.”

Einstein, as always, patiently clarified his concept.

“‘The meaning of relativity has been widely misunderstood, Philosophers play with the word, like a child with a doll. Relativity, as I see it, merely denotes that certain physical and mechanical facts, which have been regarded as positive and permanent, are relative with regard to certain other facts in the sphere of physics and mechanics. It does not mean that everything in life is relative and that we have the right to turn the whole world mischievously topsy-turvy.'”

The world of the early 20th Century certainly felt like it was being inverted — with or without relativity. Even as Einstein was developing his theory about the space-time continuum and the nature of light, old Europe was dying in record numbers. Just a few weeks before Einstein released his general theory of relativity in 1916, the German Imperial Army began its assault at Verdun. In the ensuing, ten-month battle, France and Germany suffered 800,000 casualties. Four months later, the British launched their catastrophic attack at the Somme and suffered 58,000 casualties in a single day.

The survivors of these debacles were disillusioned by the waste of this war, and the peace that followed. The youth of Europe and America were looking for new truths. The old ones seemed empty and especially lethal to young men. They saw how noble sacrifice could be used for political ends. And they had seen how virtue and faith fared against massed machine guns.

This “Relativity” they read about seemed promising, if it meant that thousands wouldn’t have to die needlessly, of that could live beyond the limiting moral codes of their parents.

Einstein, himself, didn’t indulge in any of this relativism. He was a man of strong beliefs, not equivocations. For instance, his love of music was absolute.

“‘If… I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music. I cannot tell if I would have done any creative work of importance in music, but I do know that I get most joy in life out of my violin.'”

“Einstein’s taste in music is severely classical. Even Wagner is to him no unalloyed feast of the ears. He adores Mozart and Bach. He even prefers their work to the architectural music of Beethoven.”

He disagreed with the traditional Jewish concept of free will.

“I am a determinist. As such, I do not believe in free will. The Jews believe in free will. They believe that man shapes his own life. I reject that doctrine philosophically. In that respect I am not a Jew… Practically, I am nevertheless, compelled to act as if freedom of the will existed. If I wish to live in a civilized community, I must act as if man is a responsible being.”

He never expressed any belief in a personal God, but he believed in the historical Jesus — not the popularized prophet such as appeared in a best-selling biography by Emil Ludwig.

“Ludwig’s Jesus,” Einstein replied, “is shallow. Jesus is too colossal for the pen of phrasemongers, however artful. No man can dispose of Christianity with a bon mot.”

“You accept the historical existence of Jesus?”

“Unquestionably. No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life. How different, for instance, is the impression which we receive from an account of legendary heroes of antiquity like Theseus. Theseus and other heroes of his type lack the authentic vitality of Jesus.”

Einstein was no relativist on the subject of nationalism, which he saw grow violent and intolerant from his Berlin home.

“Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.”

It was different in the United States, he believed.

“Nationalism in the United States does not assume such disagreeable forms as in Europe. This may be due partly to the fact that your country is so immense, that you do not think in terms of narrow borders. It may be due to the fact that you do not suffer from the heritage of hatred or fear which poisons the relations of the nations of Europe.”

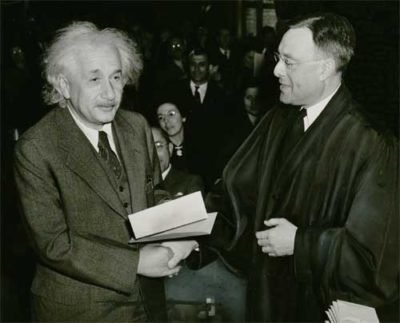

Three years later, Einstein fled Germany to seek asylum in the United States, where he became a citizen in 1940. (Not for the last time, America was enriched by the intolerance of other countries.)

It is interesting to see how Einstein viewed America three years before he made it his new home.

“In America, more than anywhere else, the individual is lost in the achievements of the many. America is beginning to be the world leader in scientific investigation. American scholarship is both patient and inspiring. The Americans show an unselfish devotion to science, which is the very opposite of the conventional European view of your countrymen.

“Too many of us look upon Americans as dollar chasers. This is a cruel libel, even if it is reiterated thoughtlessly by the Americans themselves. It is not true that the dollar is an American fetish. The American student is not interested in dollars, not even in success as such, but in his task, the object of the search. It is his painstaking application to the study of the infinitely little and infinitely large.”

The only criticism Einstein could find for America was its emphasis on homogenizing its citizens into a single type.

“Standardization robs life of its spice. To deprive every ethnic group of its special traditions is to convert the world into a huge Ford plant. I believe in standardizing automobiles. I do not believe in standardizing human beings. Standardization is a great peril which threatens American culture.”

Read “What Life Means to Einstein,” by George Sylvester Viereck. Published October 26, 1929 [PDF].

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Albert Einstein= AE

Elon Musk= EM

E=Δmc2

Thus:

AE=EM

I can be updated with any new informations regarding Albert Einstein discovery about Physics

Without imagination, there would be no knowledge. If imagination didn’t exist, the computar wouldn’t exist. None of Alberts’ creations would exist. The lightbuld wouldn’t exist, NOTHING would exist. If there was no imagination, everybody would the same, there would be no such thing an opinion. Life would be boring. That’s just the final truth. Goodbye.

Is imagination no longer relative to science?

Just check out the major U.S. search engines (Google, Yahoo, Bing, Ask) for the search term: A concept of space and time

You will find the same imagination-based essay at the TOP of each list of many millions of web sites.

Strangely, reference to this same concept has yet been hard to find in any scientific journal. What happened to imagination?

Albert Einstein did theorize

Relativity as a fact.

And it should come as no surprise

That humans seek by thought and act

To make the concept fit the way

That each one imagines as true.

And so the term gets lots of play

As all the many think and do,

And play with truth as though a toy.

In time and space he occupied,

What in his life was greatest joy?

To which Dr. Einstein replied,

“My sweetest relativity -”

“Making music with Mrs. E.”

Not sure what the inclusion of “d” represents regarding Einstein’s mathematical expression of energy’s relationship to matter. The revised formula sounds a lot like a new rap group.

Acceptance of the reality of Relativity does not foster moral ambiguity–unless, of course, you believe a hammer is the same thing as a guiding principle.

This is one of Nilsson’s better articles–though I’ve always liked all things Einstein. Had a grandfather who resembled the humble genius quite closely.