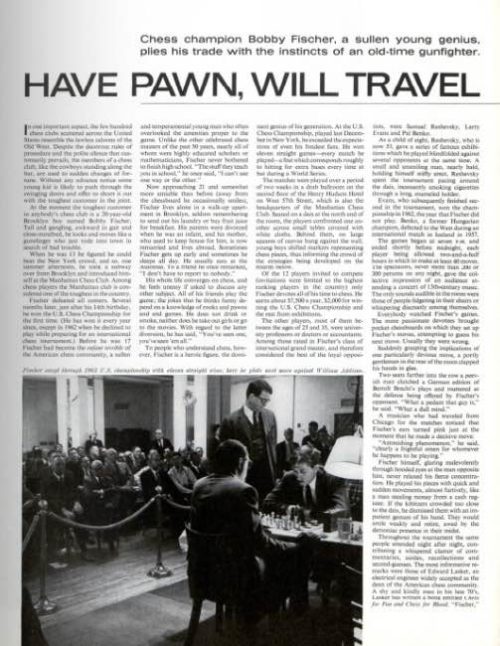

King of the Board: The Soviet Collusion Against Bobby Fischer

After a 1964 Post profile of Bobby Fischer that painted the young chess master as a rancorous loner, one reader wrote in with a prescient plea: “Please, please someone save this young man before it is too late. He needs to finish his education, find a nice girl, settle down and raise a family. He can’t spend the rest of his life just playing chess and expect to be happy.”

As it turned out, the writer of the letter, Lana Jacobs from Moline, Illinois, was right. Fischer was infamous for his anti-Semitism, paranoia, megalomania, and overall intolerability up until his death in 2008. No one ever disputed his genius at the game of chess, but — like so many at the top of their field — Fischer’s compulsiveness for the game was a likely factor in his troubled mental state.

“Have Pawn, Will Travel” described 20-year-old Fischer’s standoffishness during the 1963-64 U.S. Championship, calling his presence “demoniac.” After whipping several amateurs for one dollar per game and curtly answering the reporter’s questions, Fischer scurries off to another game: “On the way down in the elevator he frowned ominously at the other passengers and toyed with the chess pieces that he carried in his pocket.”

The article goes on to describe Fischer’s distrustful relationship with the World Chess Championship, citing that he “has never managed to win such a tournament, a failure he apparently attributes to a Communist conspiracy rather than to any shortcomings of his own.”

Two years earlier, Fischer had described his experience in the Curaçao Candidates’ tournament in a Sports Illustrated manifesto (“The Russians Have Fixed World Chess”), claiming a rudimentary grasp of Russian allowed him to sniff out their cheating: “They would openly analyze my game while I was still playing it. It is strictly against the rules for a player to discuss a game in progress, or even to speak with another player during a game — or, for that matter, with anyone.” Fischer also posed that the format of the tournament was problematic as it allowed the numerous Soviet players to collude in a series of draws and fixes, saving their energy for the finals. His suspicions were validated by several witnesses, including a Soviet grand master. One statement of Fischer’s from the article was proven false: his proclamation to never play in a World Chess Championship again.

In the World Chess Championship of 1972 — the final game of which was played 45 years ago to the day — Fischer defeated Boris Spassky and ended the 24-year-long Soviet holding of the title. The event was hugely publicized as a pitting of the West and the Communists during the Cold War, and the game of chess as a metaphor of strategy and domination didn’t hurt. The Reykavik faceoff was PBS’s highest-rated show at the time, and the whole experience even spawned a Broadway musical.

After his win, Fischer — perhaps unsurprisingly — disappeared for two decades. In the years leading to his death his anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism became hyper-inflammatory, culminating in a rant on Philippine radio on 9/11 that caused the U.S. Chess Federation to denounce the once-great player.

Fischer’s rise and fall is a tragic and puzzling tale of, perhaps, the only American household name in the game. It runs counter to most perceptions of a quiet, friendly competition that Frank Brady, the 1964 editor of Chessworld magazine, call’s “more exciting than sex.”

Weathering a Hurricane in 1950

In 1950, author Philip Wylie shared his story, “How to Live Through a Hurricane.”

Wylie was a regular contributor to The Saturday Evening Post. He was well known for his series of saltwater-fishing stories featuring Captain Crunch (no relation) and Des.

In our December 30 issue that year, he narrated the passage of a hurricane over his house in Miami. He describes how small matters, like violations of building codes, could mean the destruction of a house. Of particular interest are the preparations he made at his house before the storm: hanging heavy shutters on the window, cooking all food that would spoil if they lost power, cutting back foliage on trees, determining what to bring inside or to tie down outside.

This particular hurricane was quite different from Harvey: The major concern was wind, not flooding. And he fared much better than many residents of Houston because he had luck, time, and money on his side. What he did share with Houstonians was experience: He’d been through five hurricanes before.

Cartoons from 1925

Much has changed since 1925, but has our sense of humor? Take a look at these cartoons from 1925, and you be the judge.

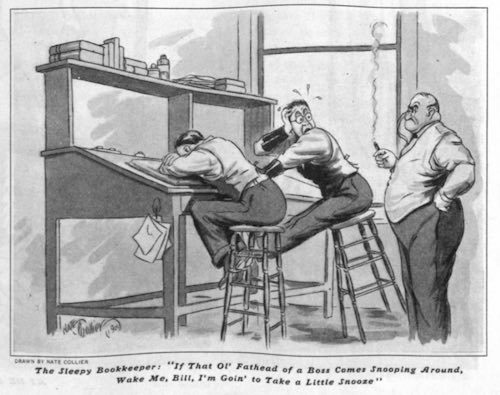

Nate Collier

June 13, 1925

Paul Goold

July 18, 1925

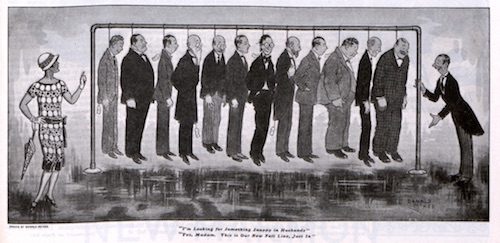

“Yes, Madam.” This is Our New Fall Line, Just In”

Donald McKee

August 1, 1925

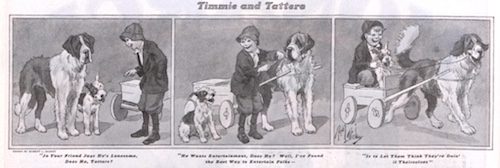

“He Wants Entertainment, Does He?” Well, I’ve Found the Best Way to Entertain Folks —

“Is to Let Them Think They’re Doin’ it Theirselves”

Robert L. Dickey

September 5, 1925

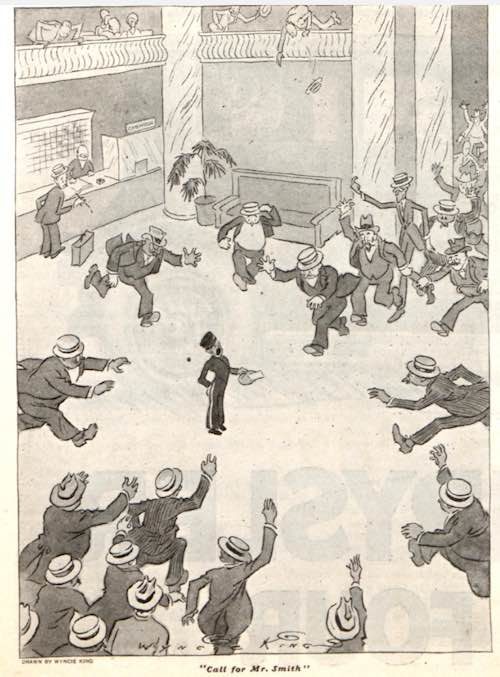

Wyncie King

September 19, 1925

Nate Collier

October 10, 1925

Donald McKee

October 10, 1925

Calvert Smith

December 26, 1925

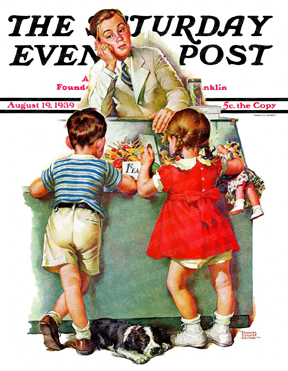

May/June 2017 Limerick Laughs Winner and Runners-Up

Between them they had just one cent.

It really wore hard on the gent.

The sweets or the sours?

They stood there for hours

Till he, and the penny, were spent.

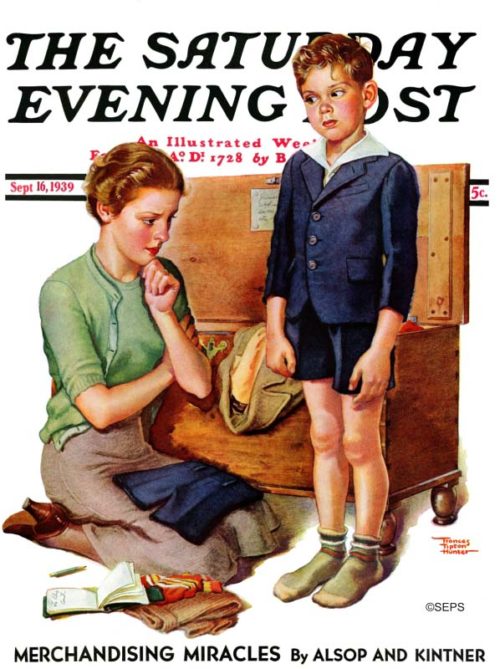

Congratulations to Cheryl Ireland of Chesterfield, Michigan! For her limerick, Cheryl wins $25 and our gratitude for her witty and entertaining poem describing Frances Tipton Hunter’s August 19, 1939, cover Penny Candy.

If you’d like to enter the Limerick Laughs Contest for our next issue of The Saturday Evening Post, submit your limerick through our online entry form.

We received a lot of great limericks. Here are some of the other ones that made us smile, in no particular order:

Our decision is made with great care

Since we’ve only a penny to share.

But if we had our druthers

We’d surely pick others

But we’d melt ‘neath the counter boy’s glare.—Barbara Wills, Blaine, Minnesota

There was a young girl named Sandy

Who had just one penny for candy.

As she savored her sweet

She was heard to repeat,

“Tough luck!” to her brother named Andy.—Brian Federico, Clyde, New York

The man on the candy sales staff

Tried hard to look bored and not laugh

When Janie and Benny

Showed up with one penny

Asking, “Please cut that sucker in half?”—Ed Tramell, Wheat Ridge, Colorado

“Though time equals money,” sighs Lenny,

“Of either I barely have any.

My time’s taken up

By these tots and their pup

While inflation devalues their penny.”—Jeff Foster, San Francisco, California

The candy shop just down the street

Is where my twins go for a treat.

The candy’s a penny

But they don’t buy many

Because they’re already so sweet!—Marcia Gwin, San Diego, California

To bask in a love is a balm

That’s so often repeated in psalm.

But the best of the many

Is a child’s last penny

That’s spent on a present for Mom.—Paul Desjardins, West Kelowna, British Columbia

As the slacker appears to be pensive,

He considers a counteroffensive

At the girl with her doll

Since she whines with a drawl:

“But a penny for sweets is expensive!”—Ryan Tilley, Altamonte Springs, Florida

“It’s been one whole hour,” he’s musing,

“And these children are nowhere near choosing.

So ten minutes more,

And that mutt on the floor

Will have some company snoozing.”—Ted Hayes, Mint Hill, North Carolina

This job is an easy position,

But based on some simple division,

You can’t pay the rent,

When the candy’s one cent

And you’re just being paid on commission.—Neal Levin, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

Donna Reed: Fire and Ice

This article was originally published on March 28, 1964.

Not long ago, as she parked her bronze Rolls-Royce at Columbia studios in Hollywood, Donna Reed spied the talkative TV personality and producer David Susskind standing nearby. He was gazing covetously at the car. The stage was thereby set for the unlikely meeting of the pretty star of ABC-TV’s Donna Reed Show and the man who, on his Open End, had attacked her series as “pure drivel.” There ensued, according to Donna, the following dialogue:

Susskind: Is this your car? If so, I must say I’m impressed. And who, my dear, are you?

Miss Reed: I happen to be your favorite TV actress.

Susskind: And who might that be?

Miss Reed: (icily) For your information, Mr. Susskind, I am Donna Reed.

Susskind: (peering through windshield) Donna Reed? Oh. Uh, er, don’t you find this car rather — uh, large?

Miss Reed: (voice raised as Susskind retreats) If you ever get a good series of your own, maybe you’ll be able to afford one just like it!

Since that encounter Miss Reed has heard no further public criticism from Susskind. She scores the incident as a point for her side. “I think Susskind is a conceited blabbermouth,” she says.

The tart tongue may seem at odds with the popular Donna Reed image, but the incident typifies the unshrinking nature of a star who occupies a select niche as one of the few female performers who still head their own series. When cornered, Donna Reed’s patience flies out the window. Six years ago, when the ratings showed that the opposition had outpointed her premiere show, the network curtly ordered her to change the format of the series, which casts Donna as the wife of a small-town pediatrician. Donna, on the phone to New York, fired back, “We’re not going to change our format. Maybe you’d better change your network.” The series not only won a quick toehold, but has proved so successful that Donna recently signed up for two additional seasons with the network.

Speaking with typical bluntness, Donna recently unloosed a pet notion of hers: “We have proved on our show that the public really does want to see a healthy woman, not a girl, not a neurotic, not a sexpot. We proved you don’t have to have an astonishing bosom or be involved in some Liz-Dickie-Eddie scandal. The public doesn’t give a damn about such things. Another thing — on my show I wear one kind of bra, and it’s not too small, and it’s not stuffed with cotton, and I’m not pushed up, pushed out, squeezed in, out or sideways. I simply wear a bra that fits. Forty movies I was in, and all I remember is, ‘What kind of a bra will you be wearing, honey?’ That was always the area of big decision — from the neck to the navel. Even with all the girl-next-door parts I played, there would usually be someone on the set whose job it was to look me up and down and say, ‘Is that dress tight enough, baby?’

“I get so fed up with immature ‘sex’ and stories about kooky, amoral, sick women. … I’m sick of this kind of misfit role, and I think the public is too.”

If pressed, Donna will sound off on other related avenues of show business in equally pungent fashion.

On Hollywood: “Everything they say about it is true. It’s a walled-in city bounded on all sides by arrogance. What’s more, the people in Hollywood who make motion pictures simply do not know about people or, often as not, about making motion pictures either.”

On actresses: “It’s a lousy profession for a woman. Being an actress turns you into a looking-glass girl, always absorbed in how you look. Always self, self, self. Too many actresses have loused up their lives because all they were capable of was taking.”

On actors: “The vanity of the average actor exceeds that of any actress.”

Donna is one of the few TV stars with an Academy Award. This triumph climaxed a fierce campaign to win the part of Alma, the prostitute who befriends Montgomery Clift in From Here to Eternity, a sharp turn from her usual roles.

Her performance in Eternity won her an Oscar in 1954. It also earned her, Donna says, the resentment of studio moguls who were unhappy about the role, which disrupted the sweet-thing image they had so meticulously fostered. “But the whole point about Alma was that she was a prostitute who didn’t look like one,” Donna says. “Try telling that to the studios. All the Oscar brought me was more bland Goody Two Shoes parts.” Over the years, Donna also has engaged in squabbles with a number of movie directors. Her opinion of that lofty profession is disdainful. “Most movie directors,” she says, “are a bunch of hackneyed craftsmen. They’re scared to death of actors and even more scared of actresses. And they hate women, which is why they make the female characters in their pictures as unpleasant as possible.”

This article is featured in the September/October 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

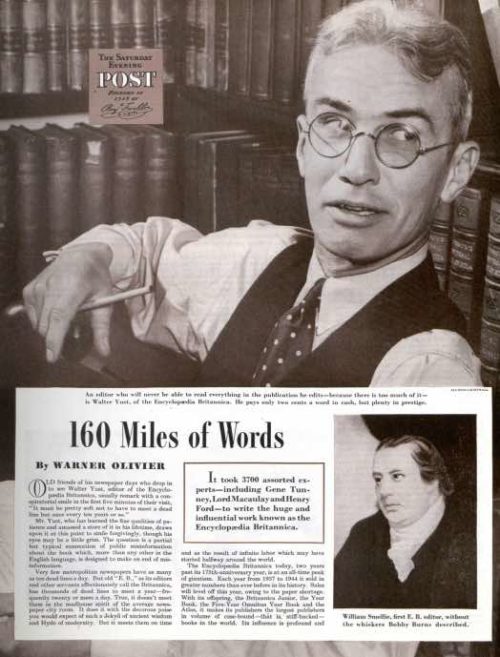

Death of a Sales Scheme: Encyclopedia Shysters of the Door-to-Door Age

Moses Pray, Ryan O’Neal’s character in 1973’s Paper Moon, cons recent widows into buying holy books with the claim that their deceased dears had put in an order shortly before passing. The heinous trick plays on the poor women’s grief and belief, powerful sentiments ripe for exploitation.

Another powerful sentiment is the wish for one’s children to grow up with culture and knowledge. It might not sell bibles; but the desire for prominence was once co-opted to peddle a pricier set of books.

Encyclopædia Britannica was in a hole when Sears, Roebuck & Co. took over the title in 1920. Britannica was sold mostly by mail-order at the time, and it only released a new edition every 25 years or so. The Post’s two-part series “160 Miles of Words” from 1945 tells the quirks and disparities of publishing such a monumental work as well as the transformation of its business practices after Sears’ secretary and treasurer E. Harrison Powell stood at the helm: “Powell started from scratch to build an outside sales organization and establish branch sales offices in key cities of the country. Sales began to go up. But strange letters of complaint also began to come into the Britannica home offices in Chicago.”

Powell — perhaps unintentionally — had employed some “old book” salesmen in his staff, and the shysters used their own tricks to get the job done: “One of their favorite methods was the giveaway, or “you-have-been-selected” trick. They would visit a prospect and tell him: ‘The Encyclopædia Britannica is initiating a new advertising campaign, and as one of the most prominent citizens of your community, we have selected you to receive a set of the Britannica free — absolutely without any cost to you.” The word “free” was as much of a misnomer as “Britannica” (the book has never been published in England) since the promise was soon followed with an offer for the newly-introduced subscriptions. The total price proved to be no bargain after all.

Powell revamped his sales department after the “shock” of discovering its unsavory business practices, and he called in a new manager to institute a rigid, thorough program for direct sales. The new protocol declared, “Appointments are made by telephone, either in the prospect’s office or in his home. If it is a home appointment, the salesman makes it clear to Mrs. Prospect that he wants to see her when Mr. Prospect is at home, so that he may talk to both of them together.”

The story of sales deception ends there, at least in the Post article. But misleading encyclopedia sales tactics never really disappeared. According to a 1968 New Republic story, all of the major encyclopedia companies have seen run-ins with the Federal Trade Commission over deceptive sales tactics as well as specious hiring ads. Britannica received a cease-and-desist order from the FTC in 1961 and a complaint in 1976. The latter claimed the book giant was misrepresenting sales jobs as advertising analysis and public relations. Furthermore, Britannica was promising salaries for their salesmen that just didn’t add up. One FTC violation sounds familiar: “Persons engaged by respondent do not contact people in their homes primarily for the purposes represented by respondents.”

Of course, Encyclopædia Britannica has ceased printing its volumes. Who needs 129 pounds of information on the shelf when you can scroll through it for free on a screen? Sure, it was authoritative, but just as Wikipedia receives flack for occasional absurdities and falsehoods, Britannica faced a learning curve with its card catalog when green editors “classified Virginia Reel under biography, Defense Mechanism under military, Gallstones under geology, Incest under business and industry, and Pope Innocent under law.”

The days of slick, smooth-talking men promising the social status only an encyclopedia set can bring to stay-at-home moms are over. Besides, people have other ways of signifying prominence these days. Unfortunately, most of them have nothing to do with knowledge.

See the Post‘s recent story, “The Death of the Encyclopedia.”

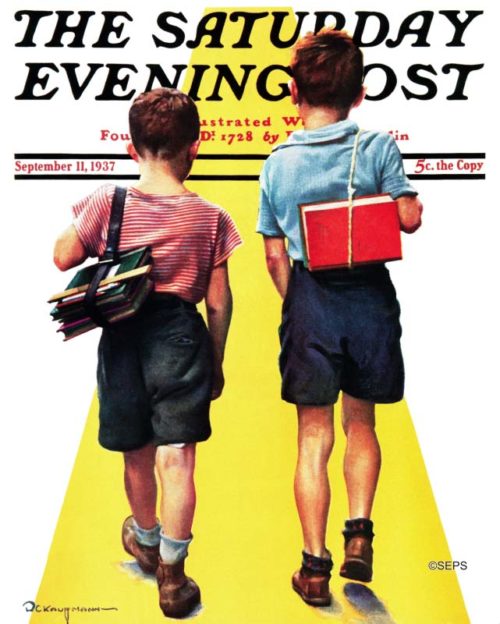

Cover Collection: Back to School

Classrooms may have changed from pencils to PowerPoint, but the Saturday Evening Post has always been there to witness sending our kids back to school.

Robert C. Kauffmann

September 11, 1937

Robert C. Kauffmann painted five covers for the Post, on a variety of subjects from pets to water skiers. With their backs to the viewer, we can only guess what these two are feeling about the first day of school.

Frances Tipton Hunter

September 16, 1939

Frances Tipton Hunter was one of the most nationally recognized artists in Post history, depicting childhood in a style similar to Norman Rockwell. Most kids grow about 2 inches each year, so this mother likely has a lot of work ahead of her.

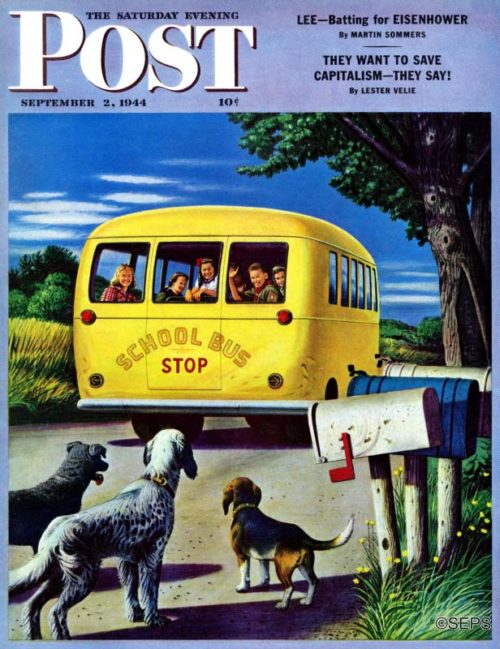

Stevan Dohanos

September 2, 1944

This is one time when the kids look happier than the dogs do about going to school.

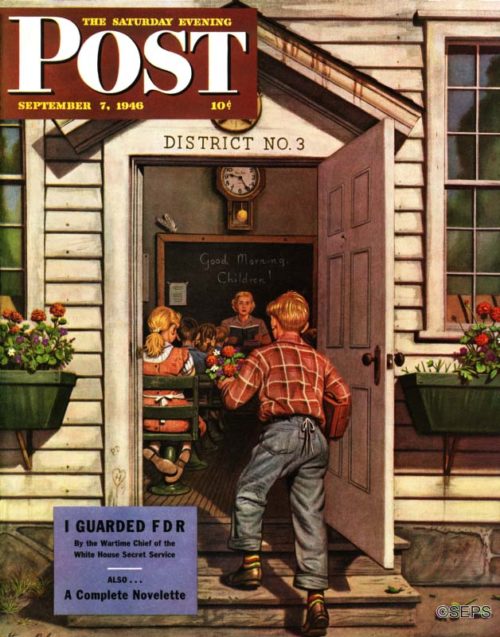

Stevan Dohanos

September 7, 1946

When Stevan Dohanos painted his picture of the first day of school, the children were brimming with excitement—not because they were posing for a cover, but because the day in question was a great day indeed. It was actually the last day of school, in June.

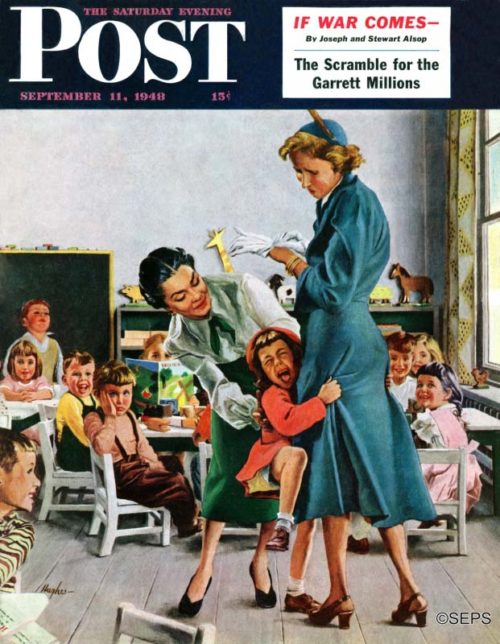

George Hughes

September 11, 1948

Artist George Hughes painted this scene at Bennington College, in Vermont, which operates a nursery school. “Do you ask me if I have any children of my own?” Hughes mutters. “Only five girls. The one who is crying on the cover is, of course, mine.”

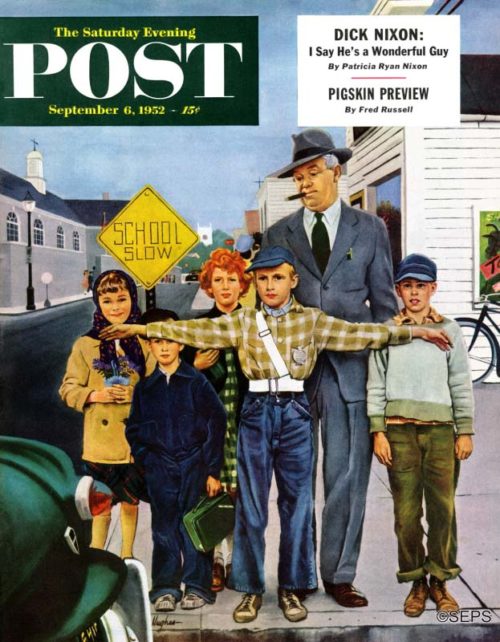

George Hughes

September 6, 1952

If artist George Hughes hadn’t stationed the young lifesaver on that corner, would that man have stepped dreamily into the street, just missed being nicked by the car, and then blamed it in loud words on the driver?

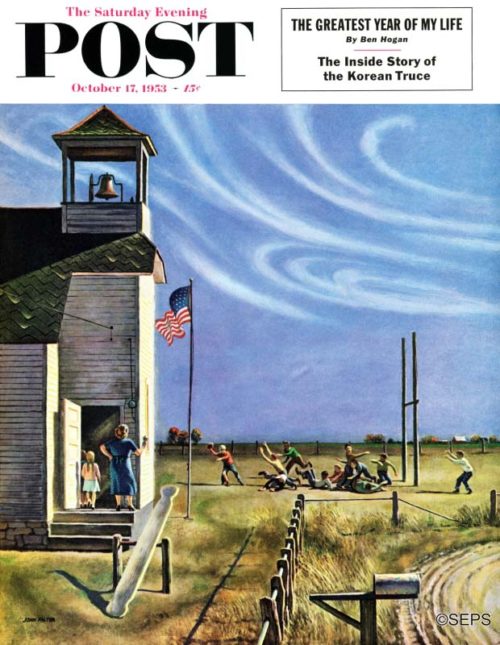

John Falter

October 17, 1953

Regarding that impending touchdown, we bet the teacher knows enough football to rule it illegal—ball was snapped after the school bell rang.

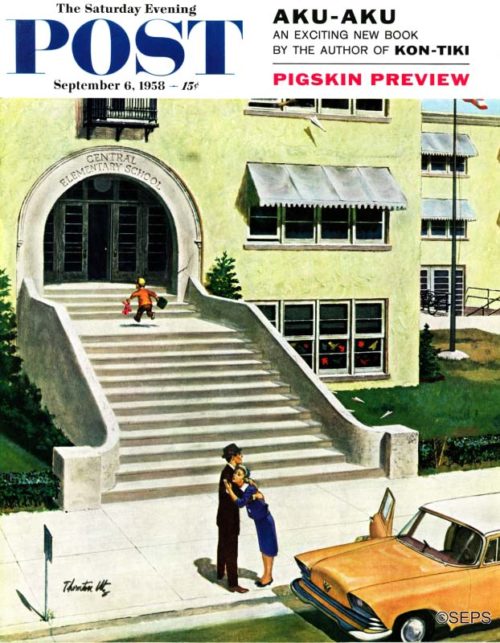

Thornton Utz

September 6, 1958

Artist Thornton Utz vows that when he was very little he liked school so much that he asked his folks if he couldn’t also go to night school. In time he got over that aberration.

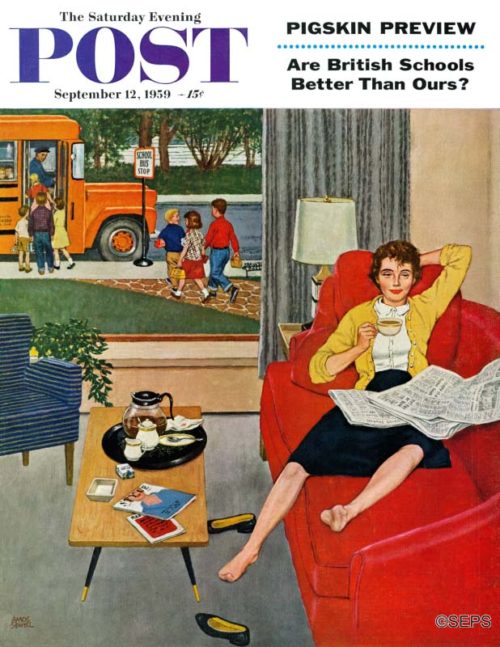

Amos Sewell

September 12, 1959

In mother’s ears is a faint, faraway ringing—would it be an echo of the youthful din that has dinned in her ears all summer, or does she think she hears what she is merely imagining, a school bell ringing? Anyway, peace.

North Country Girl: Chapter 15 — Saturday Matinee at the Norshor

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

One muddy grey spring afternoon, I was trudging home at the back a gaggle of Congdon fifth graders when a man approached us. In the early sixties there was no “stranger danger” (thus so many kids being dropped off in toy departments while their moms shopped). Duluth children were raised to be polite and helpful so we stopped and listened to him when he said “Hey kids, do you like movies?” He had a special offer, just for us. Every Saturday, there was going to be a matinee for kids at the Norshor Theatre: a cartoon, a serial (whatever that was), and a movie. He had strips of tickets printed up with the dates and the names of the movies. Each ticket was a dollar, but you had to buy the whole series of eight movies. Of course, none of us had eight dollars, I doubt if we could have come up with 80 cents among us. Not a problem, he was going around to all the elementary schools in Duluth and would be back in a few days. We could buy our tickets then.

I was giddy with excitement. I was almost too old for Disney movies, those once-a-year treats. I would have willingly sat through any movie just to go to the grand old Norshor, a vaudeville theatre that had undergone only slight renovations to show movies. There were hundreds of scratchy maroon seats, extending up through a never used balcony, seats that released with a loud “thump” when you stood up, annoying everyone around you. (My sister Lani would spend the entire ninety minutes of the Disney movie going up and down, up and down.) The ladies’ room had floor to ceiling mirrors, chrome stand ashtrays, leather ottomans with brass studs, and Art Deco wallpaper of green and pink bubbles my grandmother would have swooned over. Best of all was the snack bar, which I had always viewed as Moses did the Promised Land. I pictured myself at the kids’ movies, standing in line at the snack bar, fondling a dime liberated from the ashtray in my dad’s car, pondering: buttered popcorn? Jujubes? Sno-caps? Maybe an ice cream bar? Or a hot dog, ketchup only, plucked from its rotating metal bed. There was also a barrel of pickles for those misbegotten souls who wanted to eat a pickle while watching a movie.

I wheedled the eight bucks from my dad and along with most of my classmates, eagerly awaited the “movie man” on the day of his return.

The surprising thing is that there actually were movies. Well, for a while. The girls spent the week before the movie discussing who was going and who we would sit with. Would there be attempts at hand holding or even kissing? Then there was the rare thrill of mixing with kids from other schools. Would the tough west side greasers-in-training pick fights with the well-bred east side boys?

For a few successive Saturdays, hordes of kids, jingling with pocket change, boarded the bus downtown. Crabby old ladies learned to stay home those afternoons. We took over the entire theatre; they even opened the balcony to accommodate us.

The cartoons were the same black-and-white Betty Boops and Merrie Melodies I knew and loved. The serial turned out to be The Lone Ranger (with a different Lone Ranger and Tonto from the TV show) and the movies were marvelous. I saw Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Lost World, The Boy and the Pirates, and The Day the Earth Stood Still. I came home as if waking from a wonderful dream, slightly sticky from spilled pop, which was served in dissolving wax cups with no caps. And then it was over. The movie man skipped town, or the Norshor got tired of having to clean up after 300 kids had spent two hours having popcorn fights and pelting one another with Jujubes. The last straw many have been when Billy Shaw got the brilliant idea to smuggle in a can of Dinty Moore beef stew to the first row of the balcony, lean over while making puking sounds, then dump the contents of the can on the kids below. I looked at my four unused tickets and thought again what a cruel world this was.

***

The summer after fifth grade my family took the train to Seattle for the World’s Fair. It was a last grasp at the golden age of train travel. We had our own sleeper car, with a tiny bathroom and narrow bunks that miraculously appeared each night, thanks to a red-jacketed porter. We ate our meals in the dining car, at tables with heavy china and silverware, white tablecloth, and a single red rose in a cut glass vase, which vibrated gently as we sped along. We spent our days in the dome car, where the towering grandeur of the Rockies compelled me to take my nose out of a book for once.

It seemed that what my father, who unilaterally controlled the money and the agenda, enjoyed most about this trip was denying my sister Lani and me anything we really wanted. Scattered throughout the World’s Fair were “Pick a Pearl!” stands with tanks full of oysters. For a dollar, you selected an oyster out of the tank, which would be opened on the spot, not to eat, but in hopes of finding a pearl. I pressed my nose against the glass display of lustrous white and pink pearls big as marbles that had been found in the oysters (by whom? And why didn’t they keep their pearls?) and begged in vain for a go. My father, a gambler who had lost thousands of dollars playing poker badly or investing in sure thing oil wells, refused to part with the buck. That there was one of these stands around every corner was a constant irritation to me, like a grain of sand that had snuck into my shell.

I was also poked in the eye by the Space Needle, unavoidable from anywhere at the fair. I knew that at the top of the Space Needle was a revolving restaurant, a ride that you can actually eat on! But the Haubner family could not eat there or even take the elevator up to look at the lucky diners going round and round: my father said the line was too long. We couldn’t see the puppet show at the French pavilion, “Les Poupees de Paris”; my father thought it might be inappropriate for kids (it was a puppet show). I told Lani it was actual poops on stage and she threw such a fit at not being allowed to see this wondrous thing that we had to leave the fair immediately. Dinner at the Chinese pavilion ended in a universal family melt down, complete with tears and shouting when Lani and I spotted entire bags of fortune cookies for sale, which my father refused to buy on the grounds that we didn’t want the cookies, just the fortunes (that was true, but still: a bag of fortunes!). After Seattle we went to Vancouver Island, where I got to look at other people enjoying afternoon tea in the rose garden of the Empress Hotel. These fortunate few sat at wicker and glass tables covered with china pots, gilt-edged teacups, and tiered silver trays lined with paper doilies that held gleaming pastries and tiny frosted cakes and sandwiches with the crusts cut off. No tea for me. (Dad: “You won’t like it.”)

After the vacation of forbidden treats was behind me, I spent the next two weeks of the summer at Wanakiwin, hoping to bask in my status as a returning camper, only to find myself once more relegated to the beginners´ group in tennis, boating, and horseback riding. But there was a new crew of bunkmates who were eager to share a fount of sexual misinformation, including the news that you could get pregnant if you French kissed a boy. When another girl (not me, I was too embarrassed to reveal my ignorance) asked what a French kiss was, two girls volunteered to demonstrate at length. Lani was at camp again too, but I only saw her on the far side of dining hall, refusing to eat anything but plain spaghetti noodles and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

The minute my parents picked Lani and me up from camp, we began our “Can we go to the pool? Can we go to the pool?” chant. My mother was a hundred months pregnant, and maternity swimsuits had not yet been invented. She was not going to the pool. Somehow my parents wrangled special dispensation from the lords of Northland Country Club, and found a 16-year-old girl to drive Lani and me to the pool, where she completely ignored us, spending all her time perfecting her sunburn and attempting to attract the attention of the lifeguard. He was too absorbed in trying to never have to go in the pool (“Get back in the shallow end or get out!”) and keeping his whistle in a perpetual twirl.

On August 21st, to my father’s distress, a third Haubner girl was born. Girls I barely knew showed up at my house to ooh and aah at the adorable pink bundle that was baby Heidi (who had a narrow escape from being named Hedda), and begging to hold her. Shortly after Heidi appeared, Nana flew in from Aberdeen to take over baby care, shooing away girls who might have become my friends (“No you can’t hold this baby! The idea!”). Lani went into hiding for six months.

Somehow we all knew there would not be a Jack Haubner Junior, so at Heidi’s birth I was immediately elevated into lawn maintenance, the traditional realm of sons. My father had tried one experiment to see if I would be an acceptable substitute for a son in other areas, like fishing. In early spring, when the ice first starts to thaw, was the annual smelt run. The small silvery fish, which were more bones than flesh, were so thick in every stream and river that you could scoop them out of the water. It was the duty of every male Duluthian to go out with a net and a bottle of Seagram’s and return with 80 pounds of smelt for the freezer, where they would remain until they were thrown out to make room for next spring’s catch.

I was lying on the ratty couch in the basement rec room, knees tucked up, nose in book. My father yelled down the stairs, “Gay, we’re going smelt fishing!” I had been smelt fishing once before and had spent the entire time in the car listening to the radio and punching Lani. I had no desire to go again and my legs were curled under me for a reason: “My stomach hurts.” My father had no patience for such malingering. He rousted me off the couch and into several layers of non-waterproof clothes, and we were off to the Knife River. If you don’t feel at all well, it’s not a good idea to stand around in three feet of snow, watching fish being killed. After several netfuls of fish had been sloshed into the huge bucket beside me, I threw up. “I told you I feel sick,” I moaned as my father gazed at my puke in disbelief, as if I had just come up with a new talent for barfing at will. Then I shit my pants and got to go home.

Houston’s Problem: Hurricane Harvey 70 Years in the Making

What makes Houston unique is that no other American city has grown so big in such a bad location.

As the world watches the fourth-most populous U.S. city drowning in a death-dealing deluge, Tropical Storm Harvey appears to have more yet in store. Houston’s humid climate contrasts with arid West Texas in a big way, and — although that fact is painfully clear in recent days — substantial downpours have always come with the zone-free territory.

In the early 1800s, the area was nothing more than an empty marsh. The southwest corner of the “city” was a green-scum lake that lay under one to two feet of water. When travelers stopped to visit Sam Houston, who was living in the area in 1837, they approached his cabin by wading in water above their ankles.

Yet from 1850 on, the population nearly doubled every ten years.

The economic giant of a metropolis made for an installment of the Post’s series “The Cities of America” in 1947. In the profile, World War II correspondent George Sessions Perry gives an abiding account of Houston’s frequent torrents: “Its flat, bayou-striped acres are improperly drained, and the sight of barefooted big shots, their limousines drowned out and their britches rolled high, wading down a flooded street, is a recurrent Houston phenomenon when the sky opens up and lets drive.” Perry is dubious of the Houston Chamber of Commerce’s claim to the title of “The Sunshine City” when he opines, “Houston’s weather is atrocious.”

Every year, the city receives almost 50 inches of rain.

The author noted another of the city’s drawbacks. A lack of zoning regulations encouraged the business and residential buildings to sprawl across the country. Today, Houston is a 600-square-mile city — bigger than Chicago, Boston, Manhattan, Washington D.C., and San Francisco combined.

Houston was only able to rise above the swamp and accumulated rainfall with the help of drainage channels. There are now 2,500 miles of channels running through the city. The risk of flooding is compounded by the possibility that water in the Buffalo Bayou, a 50-mile canal connecting Houston to the Gulf of Mexico, can overflow and quickly spread across the flat surrounding countryside. Two reservoirs have been built to contain overflow, but continuing growth of suburbs keeps adding to the water load they must handle.

The city knew a better system would be needed. But the proposed improvement would involve tearing down buildings to widen the waterways at a cost of $26 billion. Meanwhile, the city continues to expand and Houston’s annual rainfall appears to be increasing

In the 70 years since Perry’s report, Houston has had its share of 500- and 100-year floods. Most recently, floods in 2016, 2015, 2006, Hurricane Ike in 2008, Tropical Storm Allison in 2001, and the Great Flood of 1994 have impacted Houston and surrounding areas. According to Texas Climate News, Houston has seen a 167 percent increase in its heaviest downpours since the 1950s, and that number is not accounting for Harvey.

Last December, the Houston Chronicle predicted that the city would flood again, “like it always does.”

A statistic like 50 inches of rainfall in a week does little to illustrate the potential harm of Hurricane Harvey. FEMA director William Long called the storm “probably the worst disaster the state’s seen.” As the nation continues to observe, donate, and assist, Houston will set out on a long road of recovery in the months to come. The city has a history of going big and leading the country in industry and resilience. As Perry noted in 1947, “[Mayor Holcolmbe says,] ‘Other cities may have better weather, bigger orchestras, but what we’ve got more of than any other city is that old bedrock thing: opportunity.’”

Featured image: Port Arthur, TX on August 31, 2017 (South Carolina National Guard)

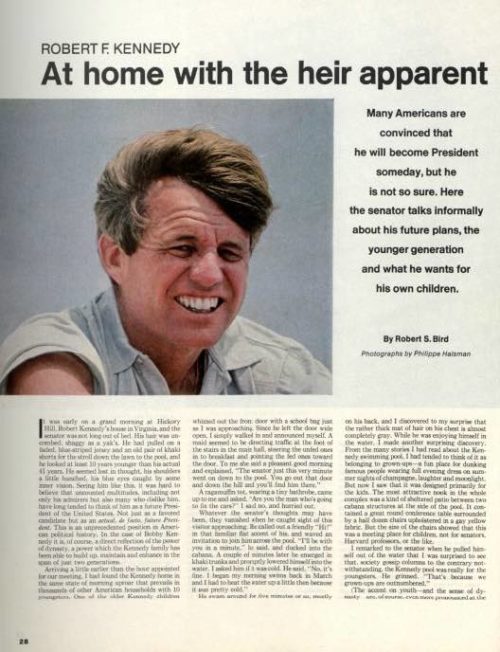

50 Years Ago: Bobby Kennedy Talks about His Future

When “At Home with the Heir Apparent” appeared in August of 1967, America was wondering whether Robert Kennedy would run for president the following year.

When “At Home with the Heir Apparent” appeared in August of 1967, America was wondering whether Robert Kennedy would run for president the following year.

He appeared a plausible challenger to President Lyndon Johnson, but he hadn’t yet declared himself and had even stated that he would not run against Johnson for the nomination. But there was a lot of support for his candidacy. Many Americans thought Robert, if elected president, would bring back his brother John’s youthful idealism.

We’ll never know what might have happened. On March 16, 1968, Kennedy began his campaign for the Democratic nomination. On March 31, President Johnson announced that he wouldn’t seek re-election.

And six days later, Robert Kennedy was killed.

News of the Week: Jerry Lewis, ESPN’s Bad Decision, and 50 Years of the Big Mac

RIP Jerry Lewis, Dick Gregory, Jay Thomas, Brian Aldiss, Sonny Burgess, Sonny Landham, Jon Shepodd, Thomas Meehan, Bea Wain

It seems like we’re losing all of the classic stars of the ’50s and ’60s. There aren’t that many left now that Jerry Lewis has died. Lewis started doing standup in his late teens and just a few years later was teamed with singer Dean Martin. The duo spent 10 very successful years together, with their own TV show and a string of hit movies, before going their separate ways in 1956. Lewis spent decades as host of The Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon (he was dumped by the producers in 2009) and went on to do several successful solo movies, many of which he wrote, produced, directed, and starred in. Lewis died Sunday at the age of 91. His death has brought out many tributes from other comics who were influenced by Lewis.

Here’s the part of the 1976 telethon where Frank Sinatra reunited Martin and Lewis after 20 years. Lewis, along with James Kaplan, wrote a book in 2005 titled Dean and Me that is worth reading.

Dick Gregory was an influential comic who later became an influential political activist. He started doing standup at Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club in Chicago in the early ’60s and in 1962 became the first black comic to sit on The Tonight Show with Jack Paar couch. Gregory died Saturday at the age of 84.

Jay Thomas was an actor and comic who appeared on such shows as Cheers, Mork & Mindy, and Murphy Brown, where he won two Emmys, and starred in two sitcoms of his own, Love & War and the underrated Married People. He was also host of his own daily talk show on SIRIUS Radio and appeared in several movies. Every year he appeared on David Letterman’s show at Christmas, where he would throw a football and try to hit the meatball on top of Dave’s Christmas tree (you had to see it to understand it) and tell a story about meeting Clayton Moore while working as a disc jockey. He died earlier this week at the age of 69.

Brian Aldiss was an acclaimed writer of many novels and short stories and is probably best known for his many works of science fiction. He died last week at the age of 92.

Sonny Burgess was a rockabilly star and Sun Records musician who founded the band the Pacers, who often opened up for Elvis Presley. Burgess was still performing up until last month and died last Thursday at the age of 88.

Sonny Landham was an actor who appeared in such films as Predator, 48 Hours, and Action Jackson and also ran for governor of Kentucky in 2003. He died last Thursday at the age of 76.

Jon Shepodd was the first person to play Paul Martin, Timmy’s dad on Lassie. When Cloris Leachman, who played his wife, Ruth, decided to leave the show after one season, producers felt they had to get rid of Shepodd too and start fresh, with June Lockhart and Hugh Reilly as Jon Provost’s parents. Shepodd died last Wednesday at the age of 89.

Thomas Meehan wrote the books for three big stage plays: The Producers, Hairspary, and Annie won him three Tony Awards. Other shows that Meehan wrote include Young Frankenstein, Rocky, Cry-Baby, and Elf. He started his career as a writer for The New Yorker. Meehan died earlier this week at the age of 88.

Bea Wain was one of the last living singers of the big band era. She sang such songs as “Deep Purple,” “My Reverie,” and “Heart and Soul,” and was actually the first person to record “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” though her recording was held back until after The Wizard of Oz came out. Wain died last weekend at the age of 100.

Bad Sportsmanship

In a time where every single week we say to ourselves “this is the craziest thing I’ve seen in a while,” I still have to say this is the craziest thing I’ve seen in a while.

Robert Lee is an Asian American college football announcer for ESPN, and the network announced this week that they’re taking him off the September 2 home opener at the University of Virginia. Can you guess why? Hint: It has to do with his name.

That’s right, ESPN has decided that Robert Lee’s name is a little too much like Robert E. Lee’s name, so they “collectively made the decision with Robert to switch games as the tragic events in Charlottesville were unfolding.” I wonder if college students even know who Robert E. Lee was?

I just hope The Saturday Evening Post doesn’t realize my first name is Robert and I live near a restaurant named Lee’s.

USS Indianapolis Wreckage Found

In the classic film Jaws, shark hunter Quint tells the story of how he was on the USS Indianapolis in 1945 when it was hit by two Japanese torpedoes. Of nearly 1,200 men on board, 300 went down the with the ship. The rest of the crew went into the water. Only 316 survived. The rest were killed by exposure, thirst, injuries, and … sharks.

The Indianapolis was lost in the sea for 72 years, but this week it was just found by an expedition funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

We've located wreckage of USS Indianapolis in Philippine Sea at 5500m below the sea. '35' on hull 1st confirmation: https://t.co/V29TLj1Ba4 pic.twitter.com/y5S7AU6OEl

— Paul Allen (@PaulGAllen) August 19, 2017

Let’s Talk about the Next Eclipse

I know, I know. We just got done with one eclipse this week and we’re already looking to the next one? It happens on April 8, 2024, and this time the path of totality will start in Mexico and go up towards New York and New England. Make sure you don’t use the same glasses you used this week, though. The lenses only last a few years, so you might as well just sell them on Craigslist as “collectors’ items.”

This is one of the best pics from the eclipse, a plane flying across just as the eclipse is happening in Lewiston, Idaho.

WOW! Kirsten Jorgensen in Lewiston, ID was about to pack up & go inside then saw the plane. She ran to the camera & click!#Eclipse2017 pic.twitter.com/6RxcXURrl3

— Mike Seidel (@mikeseidel) August 22, 2017

Millennials Hate Black-and-White Movies, Love Paper Towels

It’s always something with you millennials. First you try to destroy the cereal industry because it takes too long to clean the bowl and spoon, and then you reveal that you can’t even watch a black-and-white movie all the way through? What’s next, are you going to stop using napkins?

Yes. Business Insider has a list of the industries and products that generation Y has either killed or at the very least has hurt deeply, including casual dining places like Applebee’s and Hooters, homeownership, beer, motorcycles, golf, and napkins. Apparently, millennials are in love with paper towels (though I like to think they’re just barbarians who wipe their mouths with their sleeves) because they’re more practical than napkins and you can clean up more. But wait, aren’t millennials the ones who hate to take the time to clean even a cereal bowl?

I have to agree with one item that they don’t use anymore: bars of soap. Though I washed with Ivory every day when I was a kid, I haven’t used a bar of soap in 15 years.

Don’t be funny. I mean I use liquid soap now.

Two All-Beef Patties, Special Sauce, Lettuce, Cheese, Pickles, Onions on a Sesame Seed Bun

McDonald’s popular burger was invented by Jim Delligatti at the Uniontown, Pennsylvania, location and first served on August 22, 1967. Here’s a commercial from that same year:

Interesting that this commercial uses the line “… and a sesame seed bun” when other commercials use “on.” Okay, it’s not that interesting.

This Week in History

Dorothy Parker Born (August 22, 1893)

The witty, often caustic writer wrote for The Saturday Evening Post several times. Here are three of the poems we published in 1923, and here are 25 of her best quotes.

British Invade Washington, D.C. (August 24, 1814)

The White House was one of the buildings burned when British troops marched into Washington during the War of 1812. It was uninhabitable for three years.

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History

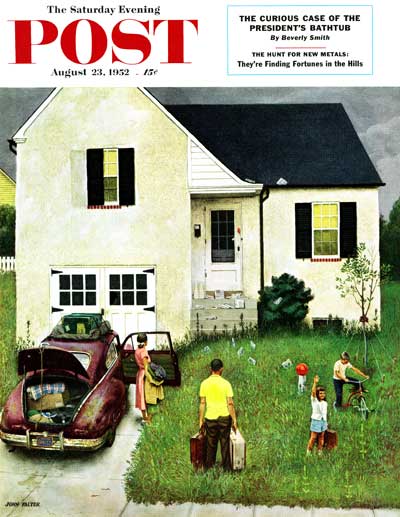

“Home from Vacation” (August 23, 1952)

John Falter

August 23 1952

Here it is, August 25, which means that summer will soon be over. Oh, sure, summer technically doesn’t end until September 22, but we all know it ends when the kids go back to school. In some areas that has already happened and in other places school starts the day after Labor Day. In this cover by John Falter, the family is coming home after their vacation and unloading the car, about to find out what bills have been piling up while they were gone.

National Cherry Popsicle Day

“Popsicle” is actually a registered trademark of Unilever, though we seem to call every frozen ice pop a “popsicle.” The same way we call every adhesive bandage a “band-aid,” even though there’s only one Band-Aid.

Anyway, I have no idea why cherry Popsicles get their own special day tomorrow, August 26. I’m an orange, grape, or root-beer guy.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

National Dog Day (August 26)

Is it a controversial thing to say that dogs are better than cats? But they are! Here’s the official National Dog Day site, where you can learn how to celebrate the day with your best friend. Cats have to wait until October 29 for their day.

Frankenstein Day (August 30)

Why is Frankenstein celebrated on August 30? That’s the birthday of author Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, which was published in 1818. On a related note, here’s a 1962 Post interview with Boris Karloff, who played Frankenstein in the 1931 film adaption.

Just for Me

I stare at the assortment of plates and platters, bowls and ramekins, cups and saucers stacked neatly on three shelves in Grandma’s silent kitchen.

“Which ones did your grandmother mean?” the woman from the lawyer’s office asks. Her voice is deep. Scratchy. Burnt. “You’re supposed to get two bowls. Are they in this cabinet?”

“I don’t know,” I answer.

“She wanted you to have your macaroni and cheese bowls. Which ones are your macaroni and cheese bowls?”

“I don’t remember,” I say. My voice is flat. Distant. Sad.

“It’s right here on the list your grandmother left. These are the things we’re supposed to distribute before the estate sale. Look at the list.”

I follow the path of the woman’s cubic zirconia-bejeweled finger down the column of names on a piece of yellow paper. The paper has been torn from a legal pad, the kind bought at an office supply store. There’s a crease in the middle of the page, running horizontally along one of the pale-blue lines dividing the paper into evenly-spaced rows. I imagine Grandma writing the list, the tip of her pen placed momentarily between her pale lips while she considers her bequests. Satisfied at last with her choices, she tears the paper from its pad, folds it along the blue line in the center, and stands. She crosses to her bed and opens her Bible, the King James version, the one with our family tree spreading across two pages, each line on the tree filled-in with a name, a date of birth, and a date of death, or left blank, anticipating death. Grandma places the paper in the middle of the Bible, between Psalm 119 and 120.

“Here’s your name.” The lady smooths the paper so that it lays flat on Grandma’s white Formica countertop. “See? Your grandmother wanted you to have two bowls.”

I stare at my name. It’s below the crease, encased in a row between the names of my older brother and my younger sister.

My gaze moves above the crease, to my brother’s name. Ross. I follow the line from his name, to the dash, to the words after the dash. My brother gets Granddad’s coin collection. Three blue books filled with shiny silver coins that Grandma placed on the top shelf of their bedroom closet 10 years ago when Granddad died. Three books with coins inside, each coin nestled into a shallow, round hole. Three books that open at the center and accordion out, first one side expanding and then the other, to showcase a gallery of walking Venuses and flying Eagles. Three books that smell of cedar absorbed from Grandma’s closet shelf. Granddad’s valued and valuable coins. Ross gets those.

The woman taps my name. Her fingertip produces a dull duh, duh on the countertop. I look at the paper and read, Andrea, follow the trajectory of the dash, and see her two macaroni bowls.

“I don’t remember,” I say again.

My eyes drift below my name to my sister’s name. Lindsay. She gets Grandma’s opal ring. Grandma was born October 9, 1927. My sister on October 18, 1979. They share an October birthdate. They share an October opal birthstone. Lindsay gets Grandma’s valued and valuable opal ring.

“So which ones?” the woman persists.

I stare into the cabinet. It’s been 40 years since I ate Grandma’s macaroni and cheese. How am I supposed to remember what bowls I ate from when I was 8 years old?

“Just take two bowls. Any two bowls. I don’t care.” Her words are clipped, rapid staccato, impatient. She lights a cigarette. Inhales. Exhales.

Cancer-carrying smoke fills my nostrils, and my eyes water.

She lifts the paper off the countertop and brings it close to her eyes. Her cigarette, pinched between her index and middle finger, dances dangerously close to the yellow paper. Ashes, clinging like magnetic shavings to the cigarette’s tip, threaten to incinerate Grandma’s last wishes. She says, “Here’s what I don’t get: Why did you need two bowls for macaroni and cheese?”

“One bowl’s for the cheese.” The whispered words escape my lips and surprise my brain. I tilt my head like a shih tzu puppy and marvel at the memory. “One bowl’s for the cheese and one’s for the macaroni,” I say, a little louder. “Grandma always grated the cheese on the fine side of the grater just for me.”

The woman makes a sound that moves across the back of her throat and exits her lips on residual smoke.

“Have you ever had cheese grated on the fine side of the grater?” I ask her. I don’t wait for a response. “Cheese grated on the fine side of the grater floats on top of the macaroni, like a canary feather on water. You have to sprinkle the cheese on the macaroni right before you take a bite.”

She gives me a look that says “you’re crazy.”

I grin. A grin that says “you don’t understand and I’m okay with that.”

I turn to look at Grandma’s kitchen table and see myself sitting in one of her metal chairs, the green plastic seat bottom sticking to my 8-year-old thighs. I’m wearing my pink gingham shorts, the ones Grandma made for me, the ones with a white poodle applique sewn onto the front of the patch pocket. The poodle’s fur is soft, formed with loops of yarn. The pocket is edged in eyelet and inside there’s a rock that I found in Grandma’s backyard, under her hibiscus plant. The rock is smooth and nearly purple.

Two bowls set side by side on the table. One is piled high with grated cheddar cheese. The other holds macaroni. I bend forward. Steam from the macaroni moistens my cheeks. A pat of butter, skating on top of the noodles, melts and vanishes. I reach for a pinch of cheese, grasp it gently between my fingers, fly the small bundle to the macaroni, and sprinkle it over the pasta. I pick up my fork and take the first bite. Golden warmth glides down my throat. I reach for another sprinkle of cheese from the yellow bowl.

“They’re yellow,” I say to the woman. “My macaroni and cheese bowls are yellow.”

I turn back to the cabinet. I don’t see any yellow bowls.

I look again at Grandma’s kitchen table, take a second bite, and hear the fork ting against the glass.

“And they’re glass. Yellow glass bowls.”

I gently lift another dollop of cheese, transport it to the macaroni, and take another bite. And another, until the macaroni bowl is empty. A pool of melted butter coats the bottom of the bowl. Sunflower yellow butter against white glass.

“The inside of the bowl is white.”

“I thought you said it was yellow?” she corrects.

“It’s yellow on the outside and white on the inside. It’s a yellow-and-white glass bowl. Bowls. Two yellow-and-white glass bowls.”

I grasp the bowl in both hands, bring it to my lips, tilt my held back, and slurp. The butter washes over my tongue. Liquid silk. When I set the bowl down, my fingers feel the ripple, ripple, ripple edge wrapping around the bottom of the bowl.

“They’re footed bowls, yellow-and-white glass footed bowls, and the footed part is rippled, like the edge of pie crust.” I look on the second shelf, move aside a stack of soup bowls, but there are no yellow bowls. I need to climb to see if they’re on the third shelf. I say to the woman, “Bring me that stepstool, please. The one by the stove.”

She hesitates and then moves to get the stool, returns, pushes against my hip with her elbow, and places the stepstool directly below the cabinet.

I climb one step. Look more closely at the second shelf. Sort through years of cups. Decades of saucers.

Climb another step to reach the third shelf. Move a green salt shaker. Shift aside a chipped gravy boat decorated with blue ships sailing on a white sea, pick up a vegetable bowl, lift it off the shelf, and peek inside.

And there they are. My macaroni and cheese bowls. Tucked away inside a floral bowl. Tucked away inside my memory.

I set the vegetable bowl on the counter and lift the smaller bowls out of their cocoon. I hold them, one in each hand, like priceless commodities, like precious jewels. I press one bowl to my cheek. The glass feels cool against my face. This is the bowl that held cheese. I bring the other to my nose and breathe in. Does it still smell of macaroni? It doesn’t. But I decide that it does.

I climb down from the stool, cradling Grandma’s macaroni and cheese bowls. My macaroni and cheese bowls.

The woman asks, “Do you want any of the rest of her dishes? Two bowls don’t seem like much to inherit from your grandmother. Your sister got a nice ring and your brother got some very valuable coins. Take something else if you want.”

“No, thank you,” I say.

These macaroni and cheese bowls are all that I want.

These two valued and valuable macaroni and cheese bowls are just for me.

Cartoons: Heaven Help Us!

September 1, 2002

July 1, 2004

March 1, 2009

March 1, 2009

November 1, 1995

March 1, 1995

But I don’t feel right without underwear.”

March 1, 1995

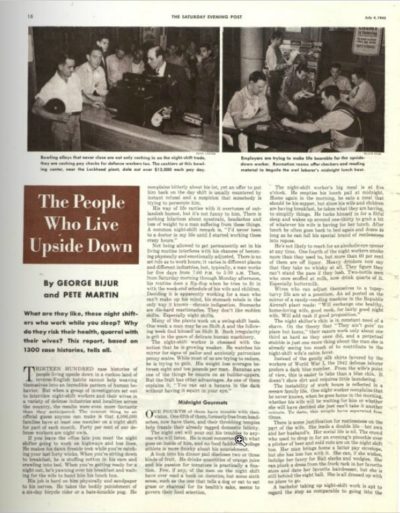

Learning to Work the Night Shift During World War II

With the war effort in 1942, suddenly many more factories were running around the clock to fulfill their defense contracts. This article from the July 4, 1942, issue of the Post looks at the toll the night shift took on workers.

Forty percent of our defense workers are night owls. The average night-shifter’s job is hard on him physically and sandpaper to his nerves. He takes the bodily punishment of a six-day bicycle rider or a bare-knuckle pug.

The night-shift worker is obsessed with the notion that he is growing weaker. He watches his mirror for signs of pallor and anxiously patronizes penny scales. While most of us are trying to reduce, he is trying to gain. His weight loss averages between eight and ten pounds per man.

One-fourth of them have trouble with their vision. One-fifth of them, formerly free from headaches, now have them, and their throbbing temples help frazzle their already ragged domestic felicity. One night worker complains that he never knows, when he goes home in the morning, whether his wife will be waiting for him or whether she will have decided she just can’t take it another minute.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Curtis Stone’s Apple Salad and Beet Dip

Shaved Fall Apple Salad

(Makes 4 servings)

The Marcona almonds used in this salad are Spanish almonds, which come roasted and lightly salted. They add a wonderful rich nutty flavor to this fresh, clean, crisp-tasting apple salad. Marcona almonds are available at specialty markets, but you could substitute regular toasted almonds if you like.

Vinaigrette:

- 2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar

- 1 teaspoon honey

- 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 tablespoon almond oil

- Sea salt

Salad:

- 2 Granny Smith apples

- ¼ cup matchstick-size strips celery, plus leaves for garnish

- 2 tablespoons fresh flat-leaf parsley leaves

- 1 ounce Manchego cheese

- 2 tablespoons coarsely chopped Marcona almonds

To make vinaigrette: In medium bowl, whisk vinegar and honey to blend. While whisking, slowly add the oils in thin stream to blend completely. Season vinaigrette to taste with salt.

To prepare salad: Using mandolin or vegetable slicer, cut apples into 1/16-inch-thin slices, avoiding and discarding cores. In large bowl, toss apples, celery, and parsley with enough vinaigrette to lightly coat. Season to taste with salt. Mound salad onto center of 4 plates. Using vegetable peeler, shave cheese into thin strips and sprinkle them over salads. Garnish with almonds and celery leaves and serve.

Make-Ahead: The vinaigrette can be made up to 1 day ahead, covered, and stored at room temperature. Rewhisk the vinaigrette before using.

Per serving

- Calories: 126

- Total Fat: 8 g

- Saturated Fat: 2 g

- Sodium: 211 mg

- Carbohydrate: 12 g

- Fiber: 2 g

- Protein: 3 g

- Diabetic Exchanges: ½ fruit, 1 ½ fat

Roasted Beet Dip

(Makes 3 cups — 6 servings)

Branch out from the dips that you’re used to and go a little beet crazy. Dukkah and homemade flatbreads go perfectly with this luscious, earthy dip. I usually chuck a couple of extra beets onto the baking sheet, then refrigerate them and slice for salads and sandwiches during the week.

- 4 medium red beets (about 1 pound total), trimmed

- 1 tablespoon olive oil

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

- 1 garlic clove

- 1 ½ cups plain Greek yogurt (fat-free)

- ¼ cup extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

- ½ cup dukkah (recipe follows)

- 4 pita breads

Preheat the oven to 400°F. In 8-inch square baking dish, toss beets with olive oil to coat and season with salt and pepper. Add ¼-cup water and cover pan tightly with foil. Roast for about 45 minutes, or until beets are tender. Allow beets to cool for 10 minutes. Using paper towels, rub beets to remove their skins (skins will slip right off). Cut enough of beets into about ¼-inch dice to measure 1 cup; reserve trimmings. Set diced beets aside.

Quarter remaining beets and combine in food processor with beet trimmings and garlic and process until finely chopped. Add yogurt, extra-virgin olive oil, and lemon juice and blend to smooth puree. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Transfer mixture to medium bowl and fold in diced beets.

To serve, transfer beet dip to serving bowl and sprinkle some of dukkah evenly over it. Serve flatbreads and remaining dukkah alongside for dipping.

Make-Ahead: The beet dip can be made up to 2 days ahead, covered, and refrigerated.

- Per serving

- Calories: 203

- Total Fat: 16 g

- Saturated Fat: 2 g

- Sodium: 223 mg

- Carbohydrate: 9 g

- Fiber: 2 g

- Protein: 8 g

- Diabetic Exchanges: 1 vegetable, ½ milk, 2 fat, 1 starch/bread

Dukkah

(Makes ¾ cup — 6 servings)

- ¼ cup hazelnuts

- 2 tablespoons sliced almonds

- 2 tablespoons coriander seeds

- 2 tablespoons white sesame seeds

- 1 tablespoon cumin seeds

- ½ teaspoon fennel seeds

- ¼ teaspoon kosher salt

- ⅛ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- ⅛ teaspoon cayenne pepper

Preheat oven to 400°F. Spread hazelnuts and almonds on separate small baking pans and toast in oven until fragrant and golden, stirring occasionally, about 8 minutes for hazelnuts and 6 minutes for almonds. Rub warm hazelnuts in cloth to remove brown skins. Cool nuts completely.

Heat small heavy sauté pan over medium heat. Add coriander seeds and stir for 3 minutes, or until aromatic and toasted. Transfer to small plate and set aside. Add sesame, cumin, and fennel seeds to pan and stir over medium heat for 3 minutes, or until toasted and aromatic. Transfer to plate and cool.

In food processor, pulse coriander seeds four times to break them up. Add hazelnuts, almonds, sesame seeds, cumin seeds, and fennel seeds and pulse until coarsely ground; mixture should be texture of coarse breadcrumbs. Do not blend to a paste.

Transfer to bowl and stir in salt, black pepper, and cayenne.

Make-Ahead: Dukkah will keep for up to 1 week stored airtight at room temperature.

Per serving

- Calories: 52

- Total Fat: 4 g

- Saturated Fat: 0 g

- Sodium: 78 mg

- Carbohydrate: 3 g

- Fiber: 2 g

- Protein: 2 g

- Diabetic Exchanges: 1 fat

Excerpted from Good Food, Good Life by Curtis Stone. Copyright © 2015 by Curtis Stone. Excerpted by permission of Ballantine Books, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Photography by Ray Kachatorian.

North Country Girl: Chapter 14 — Meet the Beatles

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

Bridgeman’s was my preferred destination after elocution lessons. Halfway between Bridgeman’s and the Patty Cake Bakery lived yet another older woman eking out a living bringing culture to the clueless daughters of Duluth’s upper middle class.

Miss Miller provided instruction in elocution and deportment in the stuffy, old-fashioned living room of her first-floor duplex. The alpha girls of Miss Johnson’s fifth grade class, Nancy Erman, Debbie Sawyer, and Betsy Strauss, had discovered Miss Miller and concocted a plan to take lessons from her once a week after school, riding the bus from Congdon to her apartment. I yearned to be a member of this clique and here was the perfect opportunity. Nancy Erman and I had been off and on friends for years; my mother highly approved as Nancy’s father was the prominent Judge Erman. Debbie Sawyer was ethereally beautiful, with long Breck Girl hair. Betsy Strauss had a blind mother she stole cigarettes from, which was the most criminal act I could imagine a girl doing.

My mother tamped down her fears about young girls on their own on the dangerous Duluth city buses, exposed to the worst elements of society for all of the ten minutes it took us to travel to Miss Miller’s apartment, and got my dad to pay. Somehow, she also got wrangled into chauffeuring us all back home after the lessons.

Miss Miller taught us the proper, ladylike way to sit down, cross our legs, enter and exit a car (using two chairs pushed together), and the correct way to introduce people (younger person to older, lower rank to upper) as if we were prospective debutants or heiresses to lost titles. The real appeal of Miss Miller’s lessons was the chance to appear on stage in her annual student recital at the Duluth Playhouse. Our elocution lessons — proper pronunciation, diction, a firm, confident speaking voice pitched at a pleasant register — were based in memorizing and performing what can only be described as doggerel, although Miss Miller referred to them as “your poems.” I was given a chestnut from the 20’s or 30’s, “I Wish my Dad Were the Janitor Man,” that is so firmly rooted in the past that no Google search can turn it up. I still have the first four lines memorized:

I wish my dad were the janitor man.

Then I could run for beer with a bright tin can.

Sample all the goodies that the grocer brings.

Dig into the trashcan and find good things.

I finally got to perform this ditty in front of a fawning audience of parents, wearing my best dress with an artful slap of fake dirt on my cheek. Of course, like everything else in my life, my sister Lani had to horn in on my elocution lessons, although she was not in the same class with us Golden Girls, thank goodness. At the recital, Lani performed the classic “After my Bath” (“After my bath I try try try/To wipe myself till I’m dry dry dry”) wrapped in a towel. I was terrified that after years of prancing around nude in our bedroom Lani would finish her act by whipping the towel off her 7-year-old Biafran refugee body, and belt out “Let Me Entertain You” clad only in her Carter’s cotton panties.

For the weeks running up to the recital, I was in heaven, not from the prospect of stardom, but from being part of the fifth grade girl in-crowd, rising from the depths of the young Ebenezer Scrooge horror of being left alone in the classroom. I lived for Wednesdays, when we boarded the bus in front of Congdon and rode by ourselves, like teen-agers, our heads huddled together in the far back seat. The hour with Miss Miller was pleasant enough. But pure bliss was the time I spent with the popular girls after elocution class. As part of this sweet deal, all of us had pocket money to spend at Bridgeman’s or the Patty Cake Shop. As we girls slouched together on the bus stop bench, talking and snacking and waiting and waiting and waiting for my mom to show up to drive us home, I felt an intense glow of belonging, combined with a sugar rush and the sensual pleasure of licking an ice cream cone or the chocolate icing off an éclair. I recognized that feeling the first time I fell in love.

Being pre-teen girls, we had two topics of conversation: the boys we had crushes on and sex. I magnanimously allowed one of the other girls to like Jim Deere since I got to ride in a car with him every day, to and from Enrichment. We had a hard time coming to agreement on the actual details of the sex act, but we knew you had to take all your clothes off. My mother’s pregnancy gave me some authority in the field; no one else could imagine their parents doing it. Betsy’s parents couldn’t possibly have sex; they had grey hair! Eventually my mom would drive up, trying to be nice to my friends while gritting her teeth while Lani launched herself like an acrobat from dashboard to back seat, and the glory would be over until next week.

The snakes in this garden were the Beatles. Sleepy, unchanging Duluth — stuck up in a forgotten corner of Minnesota, where pizza was pronounced pisa and was often topped with pineapple and ham, where the Twist had taken two years to arrive — had begun to catch up with the rest of the country. It started on November 23rd, where in the middle of the day Miss Johnson’s class was told “The President’s been shot,” and sent home to find our mothers weeping in front of the TV. For the first time we were experiencing the exact same thing as the rest of the country, connected through Walter Cronkite and Huntley and Brinkley. Then Beatlemania arrived overnight, when Ed Sullivan brought us “Something for all you young people out there,” catchy music made by four really cute guys.

I was a young fogey, dimly aware of pop music. Our car radio was constantly tuned to Duluth’s one and only music station, WEBC, my mom warbling along to “Rambling Rose” while my sister and I stopped our ears. Along with Nat King Cole, WEBC played Beach Boys and Englebert Humperdink, the 4 Seasons and Connie Francis, whatever was on the Top 40 that week, sprinkled with a few Golden Oldies. I listened with half an ear, unless the “Monster Mash” or “Alley Oop” or another silly novelty song came on. At home when I wanted to listen to music I put “Oklahoma!” or “The 1812 Overture” on my dad’s record player.

I didn’t see the Beatles that fateful Sunday night. We must have been late getting back from Carlton. My dad loved Ed Sullivan, but I had heard all the singers on the radio, thought the dancing boring, and couldn’t grasp what made the comedians funny. Only when Topo Gigio or the guy who spun plates on sticks to “The Sabre Dance” came on would my dad holler at me to come watch with him.

But at noon on Monday, February 10th, I walked into a classroom besotted (on the female side) with the Beatles. Our afterschool bus rides to elocution lessons immediately devolved into “Which Beatle do you like best?” I had a hard time telling John from Paul. I was much more interested in discussing what exactly happens when you get your period or the attractions of the real boys in our class. “Which Beatle do you like?” was like asking my favorite continent. It may have been that not only was I a year younger, but also a slower developer, so that these infatuations with unobtainable objects bewildered me. For the rest of the girls, it was as if the Beatles had rocketed them into puberty: Nancy went from playing with troll dolls to imagining how George would kiss. Debbie and Betsy sparred over Paul. I answered “John” or “Ringo” depending on which way the argument was going.

With the coming of the Beatles, the door rang shut on my childhood. Now after elocution class instead of going for ice cream or pastries, we headed to the candy racks at the small 5 & 10 in the nearby shopping plaza, where Nancy, Betsy, and Debbie agonized over which pack of Beatles cards to buy: the one featuring their favorite Beatles? Or a pack with all four of them, playing their instruments or mugging in zany poses? After these major purchases, we went back to our usual bus bench to wait and wait and wait for my mom; Nancy, Betsy and Debbie would compare and swap cards while rhapsodizing over the charms of their favorite Beatle. My mother’s daughter, I couldn’t imagine spending 10 cents for FOUR PIECES OF CARDBOARD that didn’t even come with a stick of gum and so I didn’t participate in the fun. I just didn’t get it. I slouched on the edge of the bench gnawing on a wax Nik-L-Nips bottle and longed for the Beatles to quickly pass into history.

The death blow to elocution lessons and my short-lived status as one of the popular girls came a week after our elocution recital. After school let out, the four of us boarded our usual Superior Street bus to Miss Miller’s to find that a group of big girls from Ordean Junior High occupied our favorite back seat. We crowded into a pair of seats in front of them, the Beatle cards came out, and I glumly stared out the window. I heard the girls in the back shrieking in those high pitched voices so perfected by fourteen-year-olds, and I heard the bus driver yelling at them to quiet down, which they did for ten seconds before bursting into even louder hysterics. I barely noticed the pair of biddies sitting in the front of the bus who kept turning around, casting the evil eye to determine where the mayhem was coming from.

The next afternoon the most unexpected event in the history of Congdon Elementary occurred: Nancy, Betsy, Debbie and I were called into the principal’s office. Never before had a single girl been summoned to appear before Miss Brown; her judgment and wrath was saved for the worst miscreants, the boys who fought or cursed or shoved the kid drinking from the water fountain. (“You could have broken his teeth!”)

The two elderly women in the front of the bus were good friends of Miss Brown. They had rushed to the phone as soon as they got off the bus and had been able to describe the four girls who got on at Congdon well enough for Miss Brown to quickly make an ID. She was shocked that any Congdon girl would be so disruptive in public, but girls like us? A students! We had disgraced our school. Miss Brown was not as shocked as we were. We were bug-eyed and dry-mouthed and suddenly all speaking at the same time. It was an unimaginable horror to be so unjustly accused; years later reading about the Dreyfus affair or The Count of Monte Cristo made me sweat with anxiety. It was no use crying “It wasn’t us! It was the girls in the back!” even if we had done so calmly and one at a time instead of sobbing and hiccupping. It was an adult’s word (two adults actually, members of the Crabby Old Ladies Club) against ours. We didn’t have a chance. Our parents were to be informed and we were banned from riding the city bus after school.

My mother believed me and was almost sympathetic, but not enough to face Miss Brown whose word was law. Besides, it saved her from having to drive all of us home from Miss Miller’s every Wednesday. Lani’s elocution lessons also came to an end.

At the age of 10, I learned there is no justice in this world.