After a 1964 Post profile of Bobby Fischer that painted the young chess master as a rancorous loner, one reader wrote in with a prescient plea: “Please, please someone save this young man before it is too late. He needs to finish his education, find a nice girl, settle down and raise a family. He can’t spend the rest of his life just playing chess and expect to be happy.”

As it turned out, the writer of the letter, Lana Jacobs from Moline, Illinois, was right. Fischer was infamous for his anti-Semitism, paranoia, megalomania, and overall intolerability up until his death in 2008. No one ever disputed his genius at the game of chess, but — like so many at the top of their field — Fischer’s compulsiveness for the game was a likely factor in his troubled mental state.

“Have Pawn, Will Travel” described 20-year-old Fischer’s standoffishness during the 1963-64 U.S. Championship, calling his presence “demoniac.” After whipping several amateurs for one dollar per game and curtly answering the reporter’s questions, Fischer scurries off to another game: “On the way down in the elevator he frowned ominously at the other passengers and toyed with the chess pieces that he carried in his pocket.”

The article goes on to describe Fischer’s distrustful relationship with the World Chess Championship, citing that he “has never managed to win such a tournament, a failure he apparently attributes to a Communist conspiracy rather than to any shortcomings of his own.”

Two years earlier, Fischer had described his experience in the Curaçao Candidates’ tournament in a Sports Illustrated manifesto (“The Russians Have Fixed World Chess”), claiming a rudimentary grasp of Russian allowed him to sniff out their cheating: “They would openly analyze my game while I was still playing it. It is strictly against the rules for a player to discuss a game in progress, or even to speak with another player during a game — or, for that matter, with anyone.” Fischer also posed that the format of the tournament was problematic as it allowed the numerous Soviet players to collude in a series of draws and fixes, saving their energy for the finals. His suspicions were validated by several witnesses, including a Soviet grand master. One statement of Fischer’s from the article was proven false: his proclamation to never play in a World Chess Championship again.

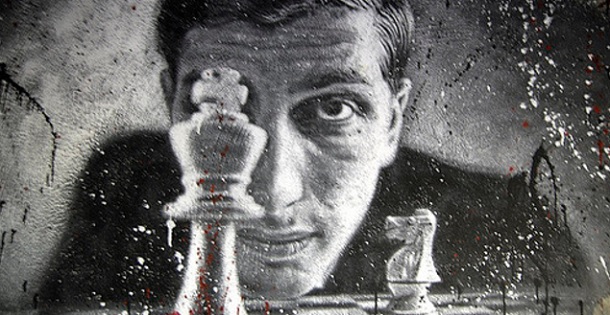

In the World Chess Championship of 1972 — the final game of which was played 45 years ago to the day — Fischer defeated Boris Spassky and ended the 24-year-long Soviet holding of the title. The event was hugely publicized as a pitting of the West and the Communists during the Cold War, and the game of chess as a metaphor of strategy and domination didn’t hurt. The Reykavik faceoff was PBS’s highest-rated show at the time, and the whole experience even spawned a Broadway musical.

After his win, Fischer — perhaps unsurprisingly — disappeared for two decades. In the years leading to his death his anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism became hyper-inflammatory, culminating in a rant on Philippine radio on 9/11 that caused the U.S. Chess Federation to denounce the once-great player.

Fischer’s rise and fall is a tragic and puzzling tale of, perhaps, the only American household name in the game. It runs counter to most perceptions of a quiet, friendly competition that Frank Brady, the 1964 editor of Chessworld magazine, call’s “more exciting than sex.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Bobby Fischer for the U.S.

Boris Spassky – U.S.S.R.

A Cold War battlefield of chess,

1972 – grand spar.

In Reykjavik, Iceland – the match

Of the century did take place.

The mind game strategies did hatch,

As West and East came face to face.

Fischer did win and did inspire

The image of a hero lone,

Conquering the evil empire –

Just a game a bit overblown.

Chess had never known such suspense,

And chess has never known such since.