The whole thing was so fantastic, so beautiful, so unbelievable, so nice.

Roscoe Hammond was moving his big, two-story house. I was there the night the truckers came with their big wheels and listened as Roscoe phoned three dozen pals.

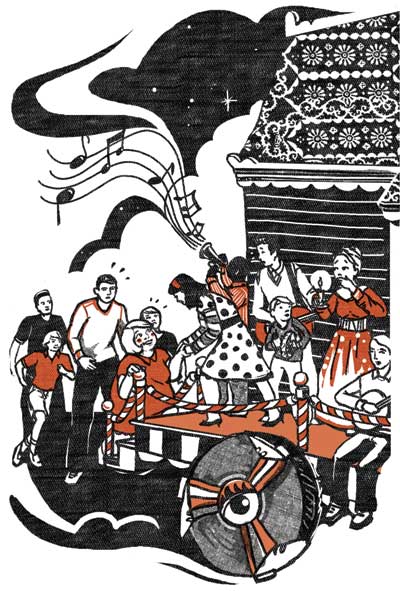

“Arnie,” Roscoe cried, “what are you doing at midnight? We’re trucking the damned house two miles uphill. Going to paint it all kinds of Hindu Bombay colors. You ever see those juggernaut films? The big icons? They roll through the streets, all different colors, and the wheels, Jesus, 5 feet round, like circular rainbows, with legs and feet and big mascara eyes.

“So what we got here is a juggernaut house moving-housewarming. But hey, Arnie, you still play trombone? Can you call the guys? I need a trumpet, a drummer, piccolos, an oboe, hell, an accordion. We’ll fill all the rooms with liquor and pals, playing Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller. We’ll gas the big bungalow and make it jump. OK, Arnie? Yeah!”

Roscoe hung up, all smiles.

Arnie showed up first, playing that brass, making us yell, “Dorsey, not dead!”

By 11:15 p.m., we had enough brass for a quintet, but we waited for Artie Shaw’s Johnny Beckett and his clarinet, thinking “Frenesi” might be the fire to run our juggernaut.

“Hell, no,” cried Arnie. “We need something wild. It’s gotta be “Chattanooga Choo Choo.” The truck drivers, all baby boomers, heard us start shouting “Chattanooga” and tromped on the gas.

The juggernaut wheels creaked and groaned. Its arms and legs spun; the big, dark, mascara eyes glared; and we were off.

Just then, the ladies began to appear in twos and threes, dropped off by rambling cars.

There were great shouts of hilarity mixed with brass, as the girls climbed aboard, carrying lit candles, like lunatic nuns.

I jumped off the juggernaut and photographed the big house moving by, like a big birthday cake, candles lit in every window.

So now we were playing and drinking and squeezing the ladies and shouting with laughter as the big, brightly colored Indian wheels of the juggernaut rolled with its arms and legs and big staring eyes. It shrugged, like an elephant in heat, with a beautiful burden of people who got louder and louder as we wheeled toward the sky.

By 11:20 p.m., Arnie moaned, “Hell, I know what’s wrong. We need real gas!”

He shouted out the window at the nearest liquor store, “Beer!” and “Vodka!” and then “Jack Daniels!” and the drinks came running.

At the same time, more musicians piled on, including Biggs Bromwell and his drums.

We were rumbling through ramshackle neighborhoods, and people came, yelling, to the curb.

“Blues in the Night.” “Love Me or Leave Me.” “Stormy Weather.” “Am I Blue?”

And then, from each room, a different player picked up a tune like “Moonlight Serenade” and flung it on to the next room for variations, and the whole house was shivering and roaring and shaking.

Things got more wild, more frantic, because even more cars were zooming up and dropping guys with their ukuleles or kazoos.

By 1 o’clock in the morning, we were taking on strangers from every jazz joint in town, and people, we heard, were on their way from San Clemente and were calling ahead to reserve a room on the juggernaut and provide a portable piano.

By 1:30 the house was so crammed with wild singers and players that we began to worry about the drag. When you’ve got 60 people in a house, that’s close to 10,000 pounds. Add five or 10 more and the whole thing begins to sink.

I climbed and sat with Arnie on the roof because there were too many elbows with the crowd down below.

So Arnie was up there, swinging his trombone, and I was there with my flute, and we were waking neighbors all along the way. You could see the lights going on in the houses on both sides as we rumbled past, and people stared out at this great big Indian elephant rolling by long after midnight.

At a little after 2 o’clock, Arnie got a worried look. “My God, we gotta be careful. If we overload this beast, we might just break free and head back downhill.”

Which is exactly what happened.

Molly, a lady friend of Arnie’s, arrived around 2:30. She was a really big lady, 250 pounds on the hoof.

Arnie cried, “Wait! How much you weigh?”

She shrieked, “That’s like asking a woman her age!”

She jumped and landed and that did it. When her body hit, our Indian elephant shivered and froze.

All the wheels creaked, the legs stopped running, the mascara eyes stopped staring, and the whole house, for a terrible instant, stood horribly still, as if it had suffered a heart attack.

Everyone sucked their breath, and we waited to see what might happen next.

Then, by God, a screeching of those big, giant, painted, multilegged, mascara-eyed wheels. The connection to the trucks came loose, and the juggernaut, in the middle of our housewarming, started to wheel back downhill.

Nobody knew what to play. There must have been a lot of talk, a lot of shrieking and gibbering, and then a genius thought, why not play Khachaturian’s “Gayne,” which was a storm inside of a hurricane inside of a cyclone. The faster the house ran, the louder the music of Khachaturian.

People leapt out of their houses, trying to run and latch onto our elephant thundering by. We thought they were trying to stop us, but no, they just wanted on for the lunatic ride.

So, with screaming and yelling, we sailed back through the middle of the night streets, past all the dark houses, waking people along the way, playing Khachaturian even louder, all the way to the sea, and out along the pier, and then to the end of the pier and off, and into the night tide.

Our juggernaut wheels spun off, all arms, legs, and eyes, and “Gayne” stopped dead. From all the rooms we heard seaside music, or ocean liner music, as the juggernaut became a houseboat with all its candles flaming, every room bright as we sailed out into the bay, and strangers on the wharf waved their handkerchiefs and sang “Farewell to Thee.” Up on the roof, I stared back because I had heard something very faint and beautiful. A rowboat was following us, with the promise of dawn ahead.

Straddled in the rowboat was Eddie Roark, stutter-plucking his big harvest moon banjo. His wife rowed as he picked and plucked “I Get the Blues When It Rains.”

“Oh, no,” I bleated. “The blues I can’t lose when it rains.”

By the time the rowboat caught up with us, I was crying.

I thought I would never stop.

Reprinted with permission by Don Congdon Associates, Inc. © 2009 by Ray Bradbury

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Wonderful! I have been an avid Ray Bradbury fan since I was 10 yrs old. I am now 58 yrs old. When I was around 16 yrs old I wrote to him. I asked for advice on budding writers. He sent me a typewritten response. Added to this, he wrote in his own handwriting some encouraging advice to me. Wonderful, wonderful writer. Wonderful human being!

Absolutely excellent!

A literary postcard to a bygone era of American music history. Bradbury never ceases to amaze with his ability to paint one glittering, joyous, tearfully nostalgic, and -above all- incredible picture. “Each little drop that falls on my window pane. Always reminds me of tears I’ve shed in vain… It rained when I found you, rained when I lost you. That’s why I get the blues when it rains.”

Bradbury is one true treasure of an American author. A gem that will never be equalled in brilliance or splendor.