[Editor’s Update: March 1, 2017] 85 years ago, the Lindbergh baby was kidnapped. Here is the story of the amateur sleuth who cracked the case.

On April 2, 1932, one month after his infant son had been taken from his nursery bed, aviator Charles Lindbergh helped deliver $50,000 in ransom to a dark figure in a Manhattan cemetery. The man gave directions to where the child could be found, then stepped back into the darkness and disappeared.

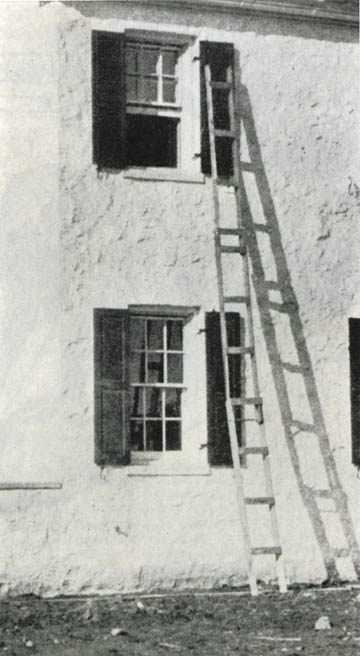

Investigators had neither a suspect nor a trail to follow. The only evidence from the kidnapping were 13 ransom notes, a chisel found outside the Lindbergh home, and a homemade ladder the kidnapper had used to reach the second-story nursery window and take the infant.

Police couldn’t even obtain evidence from the recovered child because the baby was not where the kidnapper indicated. In fact, Charles Lindbergh Jr. wasn’t even alive. He’d been killed on the night of the kidnapping and found about two months later.

For the next 29 months, the police were no closer to arresting the man who had abducted the infant son of America’s favorite hero. But one man was quietly pursuing his own investigation and making steady, slow progress toward finding the kidnapper. His story, which he told in his Post article, “Who Made That Ladder?” recounted his years of effort tracking down the man who abducted Charles Lindbergh Jr.

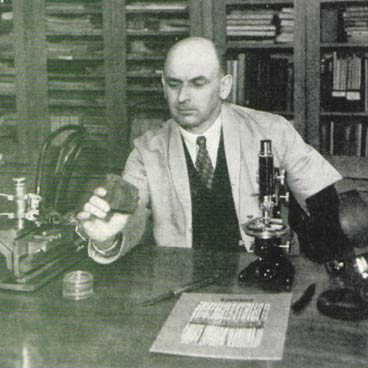

Arthur Koehler worked at the government’s Forest Products Laboratory in Wisconsin, researching new commercial uses for wood. Two months after the kidnapping, investigators from the New Jersey State Police brought him wood samples from the ladder and asked him what he could learn from them.

He quickly identified the wood as North Carolina pine. Through a microscope, he could tell the ladder had been fashioned with a plane that had a dull, chipped blade.

He noticed that the vertical rails had been previously used for something else. Holes spaced 16 inches apart showed where a square-cut nail had been driven through the board, then later pulled out.

For months, Koehler studied these pieces, particularly the slight undulations in the wood produced when the board was made at the sawmill. He concluded that the board could only have been made with a certain configuration of cutting tools. So, for the next year, he visited dozens of lumber mills, looking for the one that made boards with that unique pattern.

He finally found it in a small town in South Carolina. The mill owners told him they had shipped wood that matched the ladder sample to 42 lumberyards. So Koehler began a new search. All through 1933, he traveled to scores of cities, ruling out lumberyards with wood that didn’t match the ladder’s North Carolina pine.

Finally, in December 1933, he came to the National Lumber & Millwork Company in the Bronx. Yes, the yard foreman told him, they had received a shipment of pine from the South Carolina mill, but that was years ago. It had all been sold long ago.

However, the foreman recalled using some wood from that shipment to build a storage bin. He pulled off a piece of wood from the bin and handed it to Koehler, who quickly pulled out his magnifying glass. “One look was enough!” he wrote. “This made me positive the ladder rails had been a part of a small shipment of 2,263 feet of one-by-four-inch lumber to this Bronx firm.”

The next step was to find who had bought the wood. Unfortunately, all sales at the lumberyard were cash only. They had no receipts that might carry the name of the buyer.

So this was it, Koehler assumed. This was as far as he could go. He could trace the ladder’s wood to a lumberyard but no farther.

While Koehler was learning this from the foreman, two men walked up to the lumberyard’s sales counter. One held out a $10 bill to pay for a 40-cent piece of plywood. But when he saw Koehler, he suddenly changed his mind and left, leaving the wood behind. Thinking the men were acting suspiciously, the foreman went out into the street to get the license number of the car as the men drove away. He had recognized one of the two men, he told Koehler. It was a former employee of the lumberyard, Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Nine months later, the FBI arrested Hauptmann after he passed some of the ransom money at a gas station. Investigators immediately searched his property and found a box of the ransom money in Hauptmann’s garage.

When Koehler was called to the house, he found a wood plane that made the planing marks on the ladder. More important, he discovered that some flooring boards had been pulled from the joists in the attic. These boards had the same grain pattern and age as the ladder’s wood. He then placed a section of the ladder over the nail holes in the joists: they matched perfectly.

Koehler’s testimony proved invaluable the next year when Hauptmann was tried and convicted.

Reading through his testimony, we found an interesting point that Koehler didn’t make in his article; he conducted his investigation—two years of inquiries, testing, and travel—using only his own time and money.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now