On New Year’s Day, Congress finally, at the very last moment, passed the fiscal cliff legislation that saved the economy from free fall. Everyone on every side of the negotiations made sacrifices to make it happen. Or so it seemed. But one pharmaceutical company got wording stuck in the bill that will bring it hundreds of millions of dollars over the next couple of years.

The law ensures that Amgen, the world’s largest biotechnology business, will have two years to sell its dialysis pill Sensipar without any limits on what Medicare has to pay for it, even though the fiscal cliff bill is supposed to save $4.9 billion over 10 years by reducing overpayments for dialysis drugs and treatments. Exempting Sensipar from those controls will cost Medicare as much as $500 million.

How did the company arrange such a windfall? The provision requested by Amgen was added to the final draft of the legislation by Senate staff members, according to published reports. Why? Amgen has no fewer than 74 lobbyists in Washington, including the former chiefs of staff of both Sen. Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, and Sen. Max Baucus. It has contributed more than $5 million to candidates and their political action committees since 2007. Those lobbyists had repeated meetings with senators’ staffers in the fall. Critics contend that bowing to special interests is part of the reason for our current dilemma.

“Sadly, the lawmaker-lobbyist cabal has once again acted to serve their own financial interests; continuing to place patients at risk and passing the costs on to the taxpayer,” Dennis J. Cotter, a health policy researcher in metropolitan Washington, D.C., told the Post.

Amgen is a very big lobbying presence in Washington, but there’s nothing that special about it. Just about every business there is, from AAI Corporation to Zurich Financial, has its lobbyists prowling the halls of Congress, doing everything they can to serve their industries’ purposes, sometimes at the expense of the greater good. So does just about every special interest group.

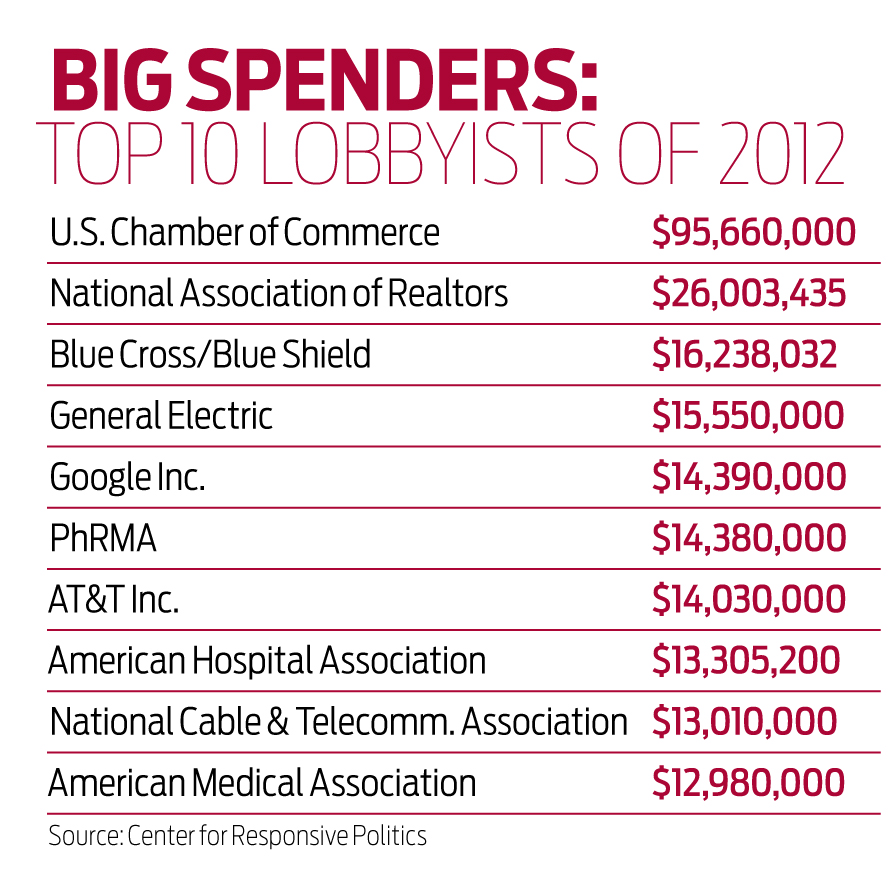

Lobbying is a huge business. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, there were 12,051 registered lobbyists in Washington in 2012, and they spent a total of $2.47 billion trying to get government officials to do their bidding. The biggest spender of all? The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which forked out almost $96 million on lobbying, followed by the National Association of Realtors, $26 million. One of the top industry sectors? Health, which spent $365 million—more than 10 times as much as organized labor.

How can so much money flowing around the nation’s capital not corrupt? It certainly does, and the revolving door between Congress and K Street, the main street of lobbying, is not just a myth. Almost two-thirds of all lobbying, in dollars spent, involves former congressional staffers. Is such a situation excusable? Should it even be legal?

Absolutely. In fact, it’s necessary. And even the founding fathers knew it. Our most revered, sacred law of all enshrines it. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution doesn’t just guarantee freedom of speech and religion. It says, in full,

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Those final words are what allows lobbying. As crucial as is our right to talk freely and worship freely, so is our right to present our concerns to Congress, and to “assemble” to do so—that is, to join forces as part of a special interest group. That’s how government works. Lobbying is as much a part of what makes representative government tick as voting or town hall meetings.

Furthermore, lobbying has evolved over time from a shady and secretive business, where outright bribes were commonplace, to a heavily regulated one, where transparency rules and where the great majority of lobbyists are open and forthright about what they do and how much they spend and why. As enormous a presence as lobbying has become in Washington (and there’s lobbying in every state capital and county and town, too), it is far more civilized and controlled and honorable today than it ever used to be. At various times, laws have been passed to make it more so, when its evils have become too undeniable.

During the very first Congress, in the 1790s, a senator wrote that a lobbyist had said “he would give [Rep. John] Vining a 1,000 Guineas for his Vote, but … he might get it for a 10th part of the Sum.” Men were already descending on Congress to try to influence votes on taxes, federal workers’ pay, veterans’ benefits, and other matters. One of the biggest earliest lobbying interests was the Bank of the United States, a quasi-government institution with enemies that included Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Its lobbyists’ activities grew so pernicious and yet accepted that in December 1833 Sen. Daniel Webster of Massachusetts wrote to the bank’s president, “I believe my retainer has not been renewed, or refreshed, as usual. If it be wished that my relation to the bank should be continued, it may be well to send me the usual retainer.” Could Tony Soprano demand a payoff more bluntly?

That’s not all Tony Soprano could relate to. According to the late Sen. Robert C. Byrd, who made a study of lobbying in the early United States, “clubs, brothels, and ‘gambling dens’ became natural habitats of the lobbyists, since these institutions were occasionally visited by members of Congress, who, far from home, came seeking good food, drink, and agreeable company.”

By 1869 a newspaper columnist could write this lurid description: “Winding in and out through the long, devious basement passage, crawling through the corridors, trailing its slimy length from gallery to committee room, at last it lies stretched at full length on the floor of Congress—this dazzling reptile, this huge, scaly serpent of the lobby.”

What exactly was the serpent up to? America’s first big industry, the railroad, was growing fast at the time, and it begat America’s first big organized lobbying effort. Laying rails across the country involved getting major government land grants and subsidies, and railroad barons hired hundreds of lobbyists at a time. Their work included giving lawmakers passes for free train travel and even cash payouts. The early railroad lobby reached an ugly peak in the Crédit Mobilier scandal of 1872, when senators and congressmen were given free railroad stock in return for passing railroad-favorable laws.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now