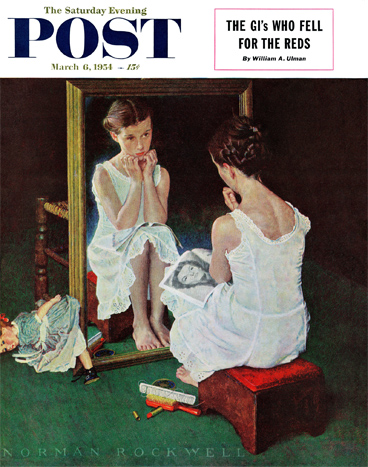

March 6, 1954

“He is a genius with a childlike heart, a man who leaves a lasting imprint on people as well as on canvas,” Mary Whalen Leonard told the Post in 1976. We spoke with her again recently to ask about one of Norman Rockwell’s most respected paintings—and about the artist himself.

Mary’s pose seems “apprehensive, as if she understands that womanhood is upon her and fears that she is not quite ready,” writes art expert Karal Ann Marling in her 1997 book, Norman Rockwell. However, young Mary didn’t have a clue.

“I was only in fifth or in sixth grade, and I wasn’t a kid who was at all interested in growing up. I was just having a good time,” Mary says.

He tried to explain the concept behind the forgotten doll: “You’ve tossed away your doll—you no longer play with dolls.” But Mary, who describes her younger self as a tomboy, says, chuckling, “I was saying to myself, ‘Yeah, I never did that anyway.’”

Rockwell knew that Mary wasn’t grasping the idea, so he tried again, “Now, Mary, don’t you ever stand in front of a mirror and wonder what a beautiful woman you’re going to be? I can remember standing in front of a mirror, combing my hair, wondering how handsome I was going to be.”

“And quite honestly,” she laughs, “that didn’t make any sense to me because Norman wasn’t handsome! So I didn’t relate to that. I mean I couldn’t get into it. So I think he just told me to think about being a beautiful woman and what I might do with my life. But it did not connect with me.”

Mary tells us Rockwell felt he had made a mistake including the magazine featuring sexy movie star Jane Russell. “He regretted it deeply. Norman got a lot of criticism—remember this was in the ’50s—that said, ‘Is that all a little girl can dream about is becoming a movie star?’”

“I should not have added the photograph of the movie star,” Rockwell later said in Marling’s book, “the little girl is not wondering if she looks like the star but just trying to estimate her own charms.”

In what would become one of his most respected paintings, Rockwell captured the poignancy and uncertainty of growing up despite the fact that Mary “had no idea what he was talking about.” For decades critics had dismissed Rockwell as simply a popular commercial illustrator. Today, many have concluded that some of his works, however, transcend freckle-faced boys at the ole swimmin’ hole and secure his standing today as a true artist. Girl at the Mirror is such a painting.

Mary, who describes this painting as “very different than most of Rockwell’s covers,” compares the subtle use of color and lighting with another of Rockwell’s finest works. “In The Marriage License,” she explains, “you think you’re going to concentrate on the couple getting their license, but really what you find yourself looking at and being drawn into is the sweet, dear man [the elderly clerk]. Because that’s where the light is, on his face.”

March 6, 1954

By the time Girl at the Mirror was published, Rockwell had moved from Vermont to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. “He wrote me a little note and told me it was going to come out. He sent me a photograph I posed for.”

Mary never knew why Rockwell called her his favorite model, but he had quickly become one of her favorite people. “I kept in touch with him until he died. He always sent me a little note at Christmas time and told me he missed me.”

See Mary today as she talks about the artist in this video, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now