Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

The age of the great locomotives ended in the early 1960s, and yet they are still missed—even by people who have never seen one in operation. Something about these massive, steam-breathing engines captures the imagination and impresses us in ways that a Boeing 747 can’t.

Many Americans who have only known interstate highways and airports yearn to see a locomotive pulling out of a station in a cloud of smoke and steam. Or hear the mournful cry of a distant steam whistle in the night. And they wonder what prompted the railroads to replace these magnificent machines with the grimy, boring diesel engines.

Fortunately, we have a Post article from the 1930s—the time when railroads introduced diesel power. “The Articles of Progress” by Garett Garrett offers a good explanation of why railroads abandoned their steam engines.

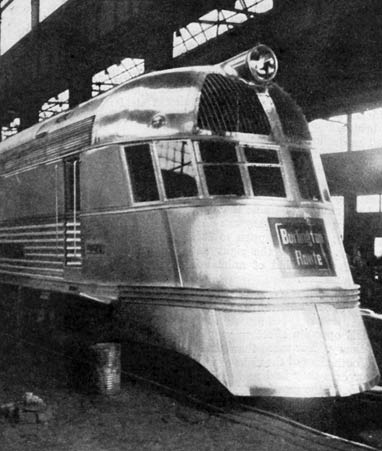

It begins with a description of Burlington Railroad’s new, fully streamlined Zephyr train and its maiden journey on May 26, 1934, across the Great Plains from Denver to Chicago.

News of the train’s passing drew crowds to the rail line in Colorado, Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois. People gathered on hills, embankments, and rooftops to see this sleek, futuristic train race past them at speeds up to 112 mph.

“Parents held out their infants in arms, exhorting them to look,” Garrett writes. “Women threw kisses wildly. Men leaped and waved their arms. Some who had come to make pictures saluted instead and forgot to turn their camera cranks.”

It wasn’t just the shining, streamlined engine and cars that excited the crowds. It was the sight of tangible change and progress in the depths of the Depression.

The 1930s were a bad time to pour money into experimental trains, but the railroad had little choice. Revenues had sunk to a dangerous level just because of struggling economy. But profits had also been declining steadily since 1920.

The only way to survive was to reduce costs and improve efficiency. Diesel power seemed to promise both.

According to the designers, diesel engines could run faster and work longer than steam locomotives. They were more fuel-efficient; they didn’t require frequent stops to replenish coal and water. Instead of generating steam in an enormous boiler, the diesel burned oil to power a generator that, in turn, powered electric motors on the wheels.

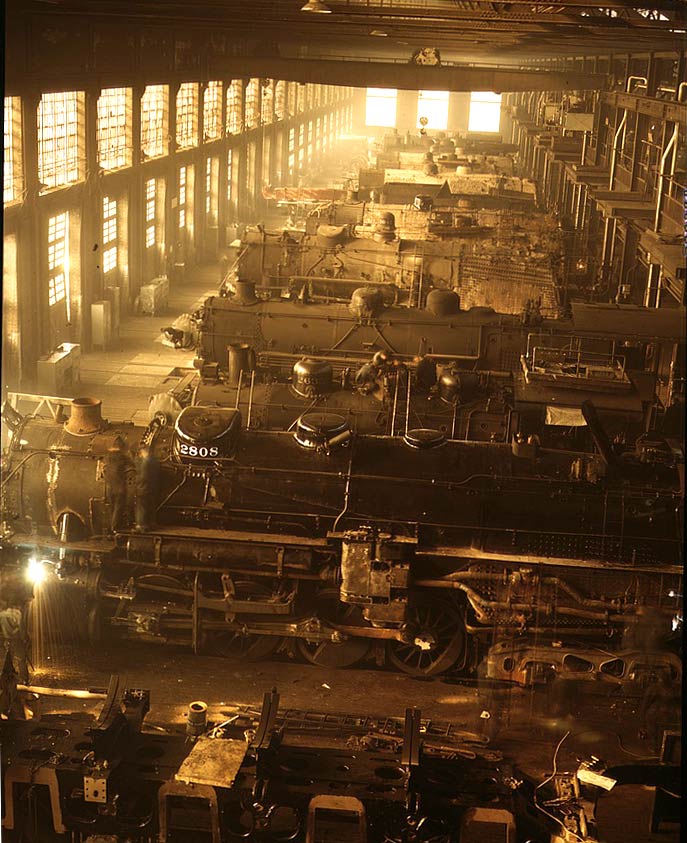

Locomotives, in comparison, had a low thermal efficiency.

They used a vast amount of energy to build up steam pressure, which had to be discarded whenever the locomotive stopped or shut down. In every week of operation, a locomotive consumed its own weight in coal and water.

“They ate too much for what they did,” Garrett wrote. “Only about one-twentieth, or 5 per cent, of the potential energy in what a steam locomotive devours is delivered to the wheels in the form of effective driving power.” In contrast, a gasoline engine could deliver more than 25 percent of its potential energy to the wheels.

Steam locomotives also required costly maintenance. Once a month, by law, the boilers had to be cleaned out. Furthermore, each engine required a regular, extensive overhaul, which meant it was available for work just 35 percent of the time. Diesel engines, which needed less maintenance, had 95 percent availability.

Because the manufacturer was using a new design for the Zephyr, the manufacturer decided to take advantage of a new construction method that used extra-light, electronically welded stainless-steel frames. Traditionally, the railroad companies had believed that adding weight to cars and engines made a train ride more comfortable. Heavier trains were also safer, they believed, because they would absorb lethal impact when collisions occurred. But as the weight of cars increased, so did the strain on rails and bridges, and with each added ton of weight, the fuel efficiency of the train dropped even farther.

The Burlington Northern railway planned to run the lightweight Zephyr train between Kansas City, Kansas, and Omaha, Nebraska, replacing a train made up of two locomotives and six heavy passenger cars. The old train weighed 1,618,000 pounds. The Zephyr would weigh just 200,000 pounds.

Two years after this article appeared, another Post article on America’s railroads reported the Burlington line had achieved a remarkable drop in operating costs. Their standard, steam-driven train had been running with an operating cost of 70 cents a mile. The Zephyr’s per-mile cost was 31 cents. The decline in rail travel had turned around. The railroads were becoming profitable again. But the steam locomotive had begun disappearing from the rail yards, taking with them the coaling stations, water towers, and the thousands of jobs that had been necessary to operate these high-maintenance engines.

As much as railroaders loved the old locomotives, they were doomed. Even as early as that first run of the Zephyr, a railway superintendant riding with Garrett confided to him, “I love the locomotive. God knows, I hate to see anything like this happen to it. But I’m a mechanic too. A machine is for what it will do. This thing skins the locomotive alive.”

Read more about the first sprint of the Zephyr and how it changed the railroad world in “The Articles of Progress” by Garet Garrett, July 28, 1934.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now