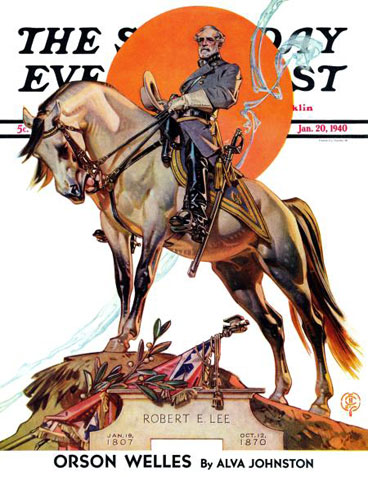

Robert E. Lee on Traveler

J.C. Leyendecker

January 20, 1940

© SEPS

Did you know President Lincoln wanted Robert E. Lee for command of the Union Army? Or that more than 10,000 Native Americans fought in the battles of the Civil War? Read on for some intriguing 19th century trivia.

The General Who Couldn’t Betray His Family

To say Robert E. Lee’s Virginian roots were deep might be an understatement. His ancestors had helped colonize the state. He was related to Virginia-born founding fathers Thomas Jefferson (by blood) and George Washington (by marriage). And there had even been land named after his family, “Leesylvania,” which is now a national park.

Lincoln had hoped Lee, who had distinguished himself in the U.S. Army in his 32 years of service, would lead the Union forces if the South were to secede. But Lee chose to remain loyal to his home in the War Between the States.

After resigning from the U.S. Army in 1860, he wrote to his brother in Virginia saying, “I am now a private citizen, and have no other ambition than to remain at home. Save in defense of my native State, I have no desire ever again to draw my sword.”

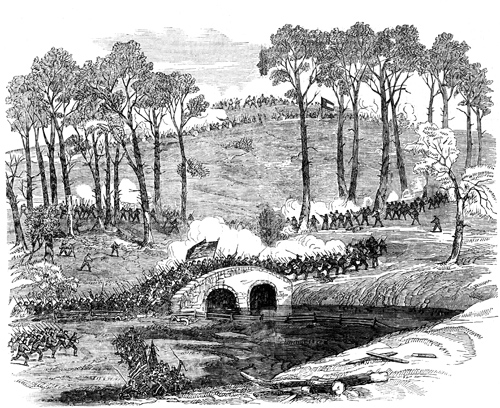

19th Century War Reporting

It is well known that the Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest day of the Civil War, with approximately 4,000 deaths and an overall casualty rate of more than 23,110. The Saturday Evening Post, which had already been around for 40-plus years by then, did not offer a “blow-by-blow” of daily events as a paper would today. Instead, it gave weekly summations of the battles and fighting and occasionally published engravings.

Unknown Artist

October 18, 1862

The intricately detailed battle scene above was published a month after the Battle of Antietam took place. The original caption from the October 18, 1862, issue reads: “Battle of Antietam, Maryland. The above, engraved expressly for the Post from ‘Frank Leslie’s Paper,’ [an illustrated newspaper of the period] represents Burnside’s division carrying the stone bridge over Antietam Creek, and storming the rebel position in front of the left wing of our army.”

[For more about the Battle of Antietam, see Jeff Nilsson’s 150th anniversary report.]

The Native American Who Became a General

Although lithographer Louis Kurz was a veteran of the war, his prints were not accurate depictions of its battles because they were highly romanticized. But Kurz did get something right in his depiction of the Battle of Pea Ridge: Native Americans did fight in the war.

Kurz and Allison

January 14, 1961

It may surprise most people today that Native Americans joined this battle. But the Confederacy promised a measure of autonomy for Native Americans and some restoration of land. Those Native Americans who chose to fight with the Union, hoped to improve their lot by rising through the ranks of the military. “All together, more than 10,000 Indians—some put the figure as high as 15,000—participated directly in the Civil War on one side or the other. Most served west of the Mississippi. The Confederacy regularly enlisted at least 5,500 [as] cavalrymen. Some 4,000 Indians are known to have served in the Union infantry. As the figures indicate, the war split the tribes as well as the states. Many were torn by doubts and questions of allegiance,” Ashley Halsey Jr. writes in the 1961 Post article “The Braves in Blue and Gray.”

One such Native American who volunteered to fight was Seneca chieftain Donehogawa. He was coldly turned down by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. This didn’t discourage Donehogawa, Halsey writes, as he was accustomed to being turned down “for simply being an Indian.”

Donehogawa (whose “white name” was Ely S. Parker) went on to study civil engineering and took a government job in Galena, Illinois. There, Halsey writes, “he befriended a former Army officer who was so down on his luck that he worked as a humble clerk.”

When he returned to his tribal reservation in New York, Donehogawa yet again requested to fight for the Union. And again he was turned down, this time by the governor of New York. “The governor, perhaps mindful that there were still some voters whose parents had been tomahawked in past wars, flatly declined to send [him] on the warpath even to save the Union.”

Not until 1863 (two years into the war) did he “manage to wangle a commission as a captain of engineers,” Halsey writes. “Quite likely the clerk whom he had befriended at Galena helped him. For by now the former clerk spoke with authority and influence. His name was Ulysses S. Grant.” From that point on, Lieutenant General Donehogawa rode beside Grant in battle as Grant’s military secretary.

“Fate reserved a modest place in history for the hawk-faced Indian,” Halsey writes. “At Appomattox, the senior adjutant, Col. T. S. Bowers felt so overcome by emotion that his hand shook. He could not write. So [Donehogawa] took the penciled draft of the surrender terms, as set down by Grant, and ‘transcribed in a fair hand the official copies of the document that ended the Civil War.’”

Reflecting on the time of surrender, Donehogawa said, “After Lee had stared at me for a moment, he extended his hand and said, ‘I am glad to see one real American here.’ I shook his hand and said, ‘We are all Americans.’”

Maurice Bower

June 1, 1935

© SEPS

The Last Civil War Veteran

The first Memorial Day—then called Decoration Day—was celebrated on May 30, 1868, three years after the last battle of the Civil War (April 1865). It was established, by the largest Union veterans’ organization: the Grand Army of the Republic. (Note the GAR hats of the three Civil War veterans at right.)

Membership to the GAR was restricted to those who served in the military during the Civil War. And although the veterans in the 1935 cover may appear elderly and even frail, the group had powerful political influence as one of the first organized advocacy groups in the United States. The group dissolved in 1956 when the last surviving veteran died. His name was Albert Woolson, and he was 109.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now