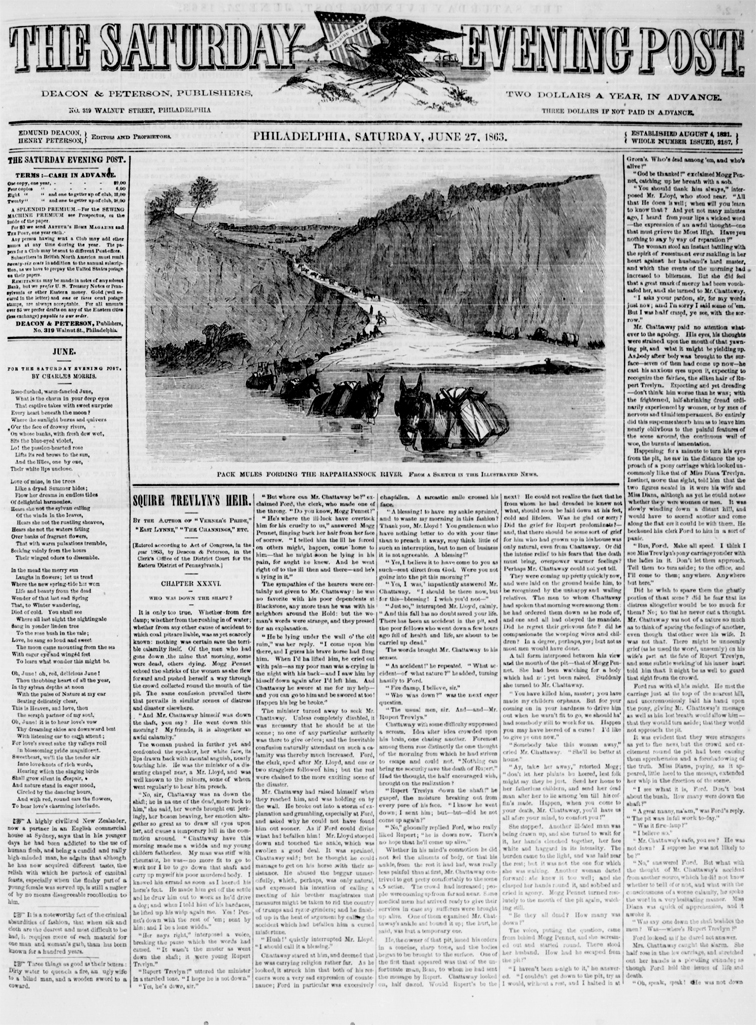

We begin a series of the Post’s reporting on the Gettysburg Campaign with the initial news of the invasion.

As was its style, the Post presented the news on Page 2 of the June 27, 1863, issue. Beneath a simple headline, “The War,” it calmly announced the opening of what would become a pivotal moment in United States history:

“Since our last issue, we have had a considerable amount of excitement in this city, owing to the reports of a rebel inroad into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Exaggerated as those reports so far have been, it is better to be prepared for the worst, than to run any risk in such a serious manner.”

The early reports were not encouraging, the article added. The federal government had believed the Confederate army, under General Robert E. Lee, was camped near Chancellorsville, Virginia, directly across the Rappahannock River from the Union army. But starting in June, Lee had quietly begun withdrawing his 70,000-man army and marching them north, toward Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Ahead of him lay only small, scattered groups of Union forces. The first to encounter the advancing rebels were the 7,000 Yankees at Winchester, Virginia. They were quickly brushed aside and then, wrote the editors, Pennsylvania “lay open for the moment to any rebel body which had the temerity to enter.”

On June 19, the Confederates had crossed into Maryland. Two days later, they entered Pennsylvania. When they reached Chambersburg on June 28, they were still 160 miles from Philadelphia, and the Post’s offices. But those miles were nearly empty of any defending troops; the Union army had begun chasing after Lee’s army on June 11, but they were still south, unable to protect Philadelphia or Washington, D.C.

Yet the Post editors remained confident that the men of Pennsylvania could, and would, throw the invaders back across the Mason-Dixon Line. They assured their readers that a state militia could be quickly formed, and it would be far more effective than expected. “We hear, in these times, a great deal of underrating of the militia, as unreliable against veteran troops. Men are disposed to think it useless to trust our safety to such a force. But it seems to be forgotten that these militia are now upon the soil of their own states, fighting in defense of all that we hold dear.”

The Post explained that militia soldiers of the South had proven they could be highly effective in pushing back the Union armies that entered their states. (Though, when they had to fight beyond their state lines, their effectiveness disappeared. “They failed thus at Antietam, and South Mountain, and Perryville, and Mill Spring, and other places.”)

The North shouldn’t dismiss the fighting skills of raw recruits, the article maintained. They had heard witnesses from several battles say raw troops had performed just as well as veteran soldiers, sometimes even better. After all, it was a hastily formed militia that won the famous Revolutionary war battle of Bunker Hill, not to mention the War of 1812’s Battle of New Orleans.

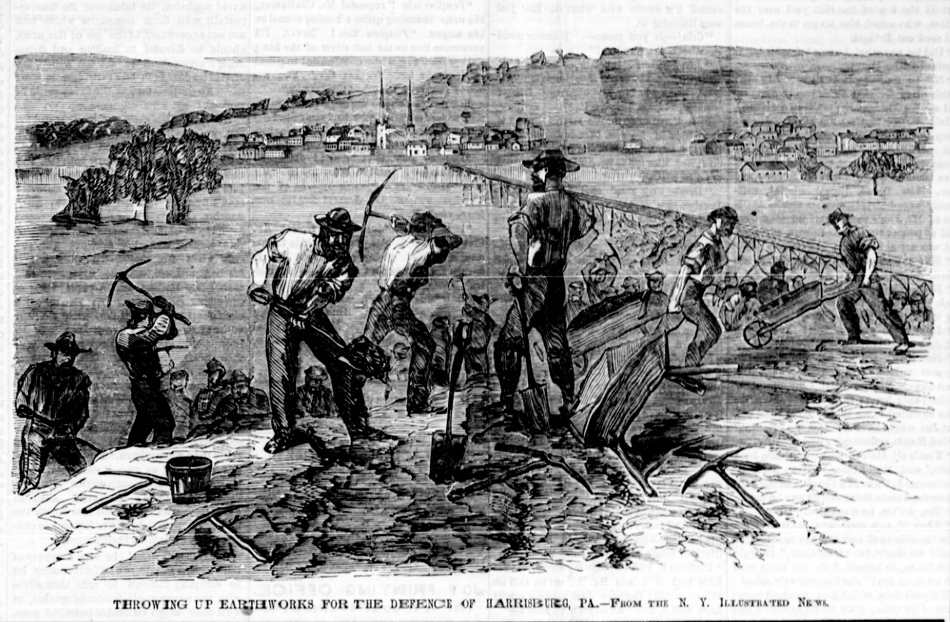

Regardless of how well this green militia could fight, it was all the state had to defend itself until the Union’s Army of the Potomac could arrive. Pennsylvania’s governor called for 90,000 men to form a state militia, and hundreds of men traveled to Harrisburg to muster in. But when they arrived, many changed their minds upon learning the enlistment period of six months was longer than they thought necessary to meet the crisis.

Instead of criticizing their lack of spirit, the Post agreed with the volunteers’ decision not to enlist: “We do not censure in the least, those of our citizens who recently returned from Harrisburg, because their business engagements did not admit even a conditional pledge to serve for six months.” If the emergency were truly short-lived, they argued, there wouldn’t be any need for such a long enlistment.

Seeing the poor response, the governor reduced his request to 60,000 men and an enlistment of just three months.

While the debate about terms of service continued, the Confederates were helping themselves to the riches of Pennsylvania. Rebel troops who had long been living on short rations in a countryside ruined by war suddenly found themselves among the fat livestock and bulging granaries on Pennsylvania Dutch farms. Lee had ordered his men not to take from the local farmers, but to pay for what they requisitioned in (valueless) Confederate money. But many Confederates didn’t bother with such niceties as payment as they helped themselves to livestock, crops, furniture, clothing, and anything that could be loaded onto a wagon. Even worse, several hundred black Americans—some escaped slaves as well as fourth-generation free Pennsylvanians—were being seized and sent south to be sold as slaves.

No one in the North could be sure where Lee was headed, or what he had in mind. A report filed in the Post on June 28 indicated Harrisburg was the likely target. “The capital of the state is in danger. The enemy is within four miles of our works and advancing. The cannonading has been distinctly heard for three hours.”

Northerners knew that if Lee could take Harrisburg and its resources, he might easily turn southeast and seize Washington, D.C., just 120 miles away.

The Post’s editors never lost faith in Pennsylvania, or the Union. They believed Lee had made a bold move, but a hazardous one. “Properly improved on the part of the North and the Government, it may have the most favorable results. Let the friends of the Union seize now the propitious moment.”

What the Post didn’t know was that the Union army was closer than they, or Lee, expected.

Coming Next: Scrambling for Troops

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now