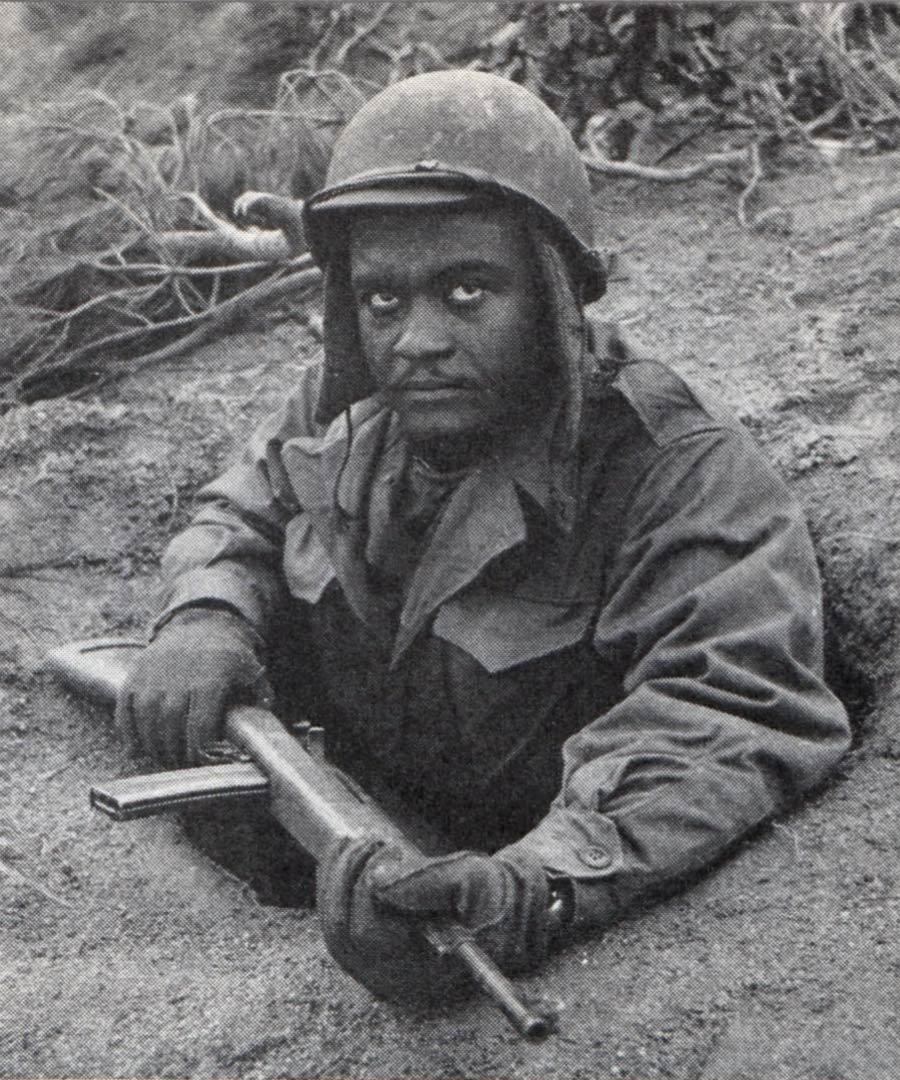

We begin a new series on “The Long March on Washington” by looking at a 1940s article about wartime opportunities for black Americans.

Popular history tells us that the March on Washington began on the morning of August 28, 1963, when more than 200,000 Americans gathered at the Washington Monument and progressed to the Lincoln Memorial.

But the March actually began 22 years earlier, as America was being drawn into World War II. To prepare its defenses, the government had brought back the draft and placed large orders for armaments with the nation’s manufacturers. Young men could choose to enlist with the service of their choice, or take advantage of lucrative defense work—if they were white. But few wartime opportunities existed for black men.

As Walter White, secretary of the NAACP, wrote in the Post, “The Negro insists upon doing his part, and the Army and Navy want none of him.”

White’s article, “It’s Our Country, Too” (December 14, 1940), cited numerous instances in which the military turned away qualified black men. For example, when a skilled black pilot applied to the Army Air Corps, he was flatly told by the recruiting officer, “There is no place for a Negro in the Air Corps.”

A black enlistee with a degree in pharmacology was told, “We’re not going to have any black pharmacists in the Army.” A black volunteer at a southern recruiting station was told it was for “whites only” and, when he questioned this policy, was savagely beaten before being thrown out onto the street.

At the time of his writing, White said, the regular Army had just five black officers. Three of them were chaplains. However, the Army readily accepted black men to serve as cooks, truck drivers, sanitation workers, and grooms in cavalry stables.

If a black man applied to the Navy, White said, he ran into even greater resistance. “Until [World War I] it was possible for Negroes in the Navy to attain the rank of petty officer. Nowadays, they are permitted to enlist only as menials. They can rise only to the position of officers’ cook or steward.” An assistant to the Secretary of the Navy wrote that this policy “was adopted to meet the best interests of the Navy and the country, [and] the men themselves.”

As for the marines of 1940, White wrote, “no Negro has ever served, either as an officer or an enlisted man, in the Marine Corps

Meanwhile, employment opportunities were opening up in factories that had received large government contracts to produce weapons. Black Americans found most of these opportunities closed to them. White reported that skilled black workmen found it impossible to gain employment in shipyards where unions only permitted hiring “members of the white race.”

An airplane plant in Nashville, Tennessee, planned to employ more than 7,000 men, but a company representative told White, “I am not certain at the present time how many colored people will be employed in our plant. As far as I know, there will be very few. There possibly will be some porters and truckmen.”

Discrimination wasn’t only found in the South, however. White reported that an airplane manufacturer in New England told the federal employment offices that “Negro applicants should not be sent, and that if they were sent they would not be hired.”

In September of 1940, White and A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to find ways to end segregation in the military and industry. Roosevelt agreed to create more opportunities for black servicemen in every branch of the service, including combat units. But he felt he couldn’t integrate black and white soldiers in the same regiments.

Randolph pleaded for more opportunities for blacks in defense plants, but Roosevelt was reluctant to use his office to end discrimination. So, early in 1941, Randolph proposed staging a large-scale protest. Setting up a March on Washington Committee, with offices in 18 major cities, he planned to bring thousands of black Americans to the capital. They would march down Pennsylvania Avenue to bring attention to the discrimination in defense plants.

Now it was Roosevelt’s turn to need a favor; he asked Randolph to call off the march. The president felt the protest would diminish his efforts to build national unity for the impending war. In the end, Randolph called off the march after the president agreed to issue an executive order prohibiting discrimination in any plant with a federal defense contract.

The armed forces remained segregated for the duration of the war. Black men distinguished themselves in several infantry, cavalry, and artillery divisions, as well as two marine divisions and the 332d Fighter Group, the Tuskegee Airmen. Finally, in 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the military to integrate.

Randolph’s challenge marked the beginning of a new era in the struggle for civil rights. For the first time, a black leader had negotiated from a position of strength because thousands of black Americans were ready to support massed action.

Coming Next: Panic in White Neighborhoods

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now