Click here to license “The Hurried Cleanup” by Thornton Utz.

Click here to purchase artwork from Thornton Utz at Art.com.

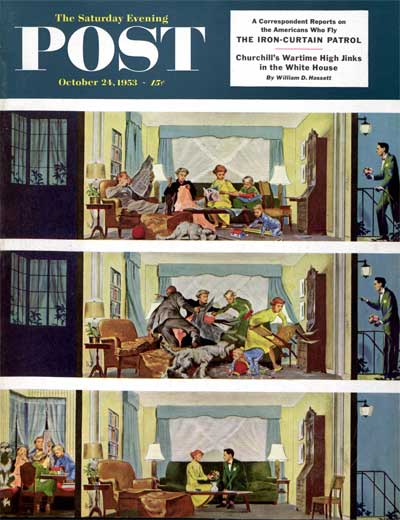

This three-paneled illustration from the October 24, 1953 cover of The Saturday Evening Post tells a humorous story about the reality of life in the home of an American nuclear family. In the 1950s era of perfectionist “Honey, I’m home!” television shows such as Leave it to Beaver and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, this cover gently tweaks American sensibilities by presenting the messier side of family life.

It’s an amusing story, in which a family must react to the arrival of an unexpected guest by engaging in a frenzied cleanup. But behind the charm of the subject matter lies a great deal of skill and engineering. If, on the surface, we are looking at three simple scenes that progressively tell a story, the artist, Thornton Utz, skillfully uses compositional framing of the work to guide viewers’ eyes across the piece in a precise way.

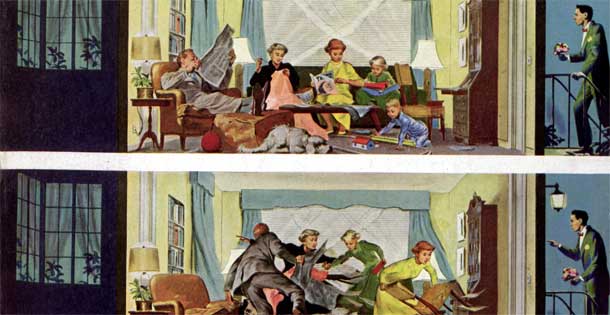

Let’s start with his use of contrast. There’s the bright yellow living room at the center of the first frame. To the right of the living room, the front stoop is depicted in the fading light of dusk. On the left, the kitchen is pitch black with little light entering the window. The dark frames on either side of the living room serve to encapsulate the important family space as a kind of cocoon. Our eyes look at the overly lit middle column placed in a warm setting of early evening.

Because he’s in motion, the young man walking to the door gets our immediate attention. By the illustration’s second frame, the action shifts to the middle column as the family rushes to make their home presentable. In the third frame, calm has returned. But the sharp contrast of the now-lit kitchen draws the eye to the bottom left frame. In effect, the artist has moved the story forward from the top right frame across the middle, down to the bottom left of the picture.

Notice, too, how the horizontal white lines clip each frame of the illustration like a filmstrip. They keep the spatial settings separate, clarifying the progression of the story as if we were looking at an actual motion picture. But unlike a movie, the illustration is divided into three horizontal frames and three vertical columns. Each ninth of the illustration affords the viewer an opportunity to look in on individual aspects of a scene as it unfolds.

In the final panel, the rest of the family, having moved to the kitchen, has reverted to a state of relaxation in the now available third room. Just as the artist employed visual contrast to tell the story, he is describing a psychological contrast between our messy interior lives and the neat façade we present to the outside world. The viewer relates to the mess, the frenzy, and the successful maintenance of proper etiquette. This family has quickly and effectively made their reality live up to the ideals of the era—but it was a close call.

To learn more about Thornton Utz and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.

To learn more about Thornton Utz and to see other inside illustrations and covers from this artist, click here!.Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great artistic and sociological insight into a wonderful Thorton Utz cover, that’s a lot deeper than it seems on the surface. Most people would just get the bottom line of “Oh no—it’s not perfect, and we better get it that way—FAST”, which they proceed to do.

This cover is four years older than me, but my own insight into the time period’s perfection premium I believe stems in part from the tumult of the Deptression and World War II; about 1929-’46, so these were the years when it seemed possible to have it again, and there was pressure TO have it, or at least seem like one had it.

It extended past the ’50s as well. Carol Brady, though a ’70s TV housewife, and in a state-of-the-art time capsule for that decade, wasn’t too much different except for the clothes and the hair styles. The show itself not so much either. Both eras do show an exaggerated perfectionism, but not ridiculously so. Up to about 40 years ago, Dad’s salary allowed Mom to be a stay at home Mother if she chose. Except for ‘Hazel’ Mrs. Brady even had a maid the earlier TV housewives didn’t have, to do the real work.

Today, Frankie Heck as the Mother in ‘The Middle’ is pretty much an exact counterpart of June Cleaver, Donna Reed or Carol Brady of the drastically different America (to put it mildly) we live in today. She too is exaggerated somewhat, yes, but only to the same degree as her mid-early late 20th century counterparts. The former in a nation of general orderliness; the latter in a fast paced, stressed out, burned out, chaotic, overwhelmed mess.