“There’s too much sex and violence in film!” This is an argument we’re used to hearing today, but did you know this accusation has been levied against Hollywood as early as the 1920s?

In what is commonly referred to as the “pre-code” era, American cinema had no restraints on objectionable content.

But in 1915, the Supreme Court decided that film was not art, because it was meant to generate profit and thus should not be protected by the first amendment.

In the case of Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the judges reached a 9-0 decision that “The exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit…not to be regarded, nor intended to be regarded by the Ohio Constitution, we think, as part of the press of the country, or as organs of public opinion.”

Realizing that this ruling could mean government oversight of the film industry’s as-yet unregulated operations, the studios moved to head off a federal censorship board. In 1922, they created the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) organization.

William Hays, the former Postmaster General and head of the Republican National Committee, was chosen to lead the organization, a calculated move to provide sway with leaders in Washington. The MPPDA intended to show D.C. politicians that federal censorship wasn’t necessary, as the studios were censoring themselves. Yet through the early 1930s, the MPPDA made little attempt to regulate film.

As the Great Depression started and expendable incomes all but depleted, American filmmakers struggled to fill the seats. To coax the public back the the theaters, filmmakers resorted to increased use of sex, violence, and other not-necessarily-wholesome gimmicks in their movies.

When the MPPDA did nothing to clean up the new sensationalism in cinema, other groups sprang up to take matters into their own hands. State and city censorship boards were already scattered across the country, but they began to flex more power. And then the Catholic Church decided to take action.

Fed up with the lack of censorship in Hollywood, Catholic bishops founded the Catholic Legion of Decency in 1934. Their self-anointed task was to clean up cinema with a three-tiered rating system, and churchgoers across the country were told that all good Catholics must adhere to the standards set forth by the CLD. The ratings: an “A” film was deemed “morally unobjectionable” ; a “B” film was deemed “morally objectionable in part” ; a “C” film was “condemned.”

Negative press from boycotts on some films and the financial losses that followed finally pushed the MPPDA to act. Though a code of decency–often referred to as the Hays Code, named for the head of the organization–had been written in 1930, a loophole in policy had kept the rules from ever being enforced on the film industry. Now, thanks largely to the actions of the Legion of Decency, the years of the MPPDA turning a blind eye had come to an end.

In 1934, the MPPDA established the Production Code Administration (PCA) to be the enforcement arm of the establishment, headed by Joseph Breen.

The code comprised a list of “Do’s” and “Do Not’s” for filmmakers, and any film that didn’t adhere to the standards would be denied an MPPDA stamp by the PCA. Since the studios, all members of the MPPDA, owned the vast majority of theaters at the time, any film without a MPPDA stamp was barred from being shown at almost every theatre in the country.

Thus the MPPDA, the PCA, and the National Legion of Decency (they replaced “Catholic” with “National” in 1934) coexisted harmoniously for decades. A film with a C rating from the NLD was rejected by the PCA, and vice-versa.

Film stars known for their sexuality like Mae West were virtually put out of business, the gangster genre was forever altered, and political and social pressure eased. State censorship boards stopped making changes almost all together. Then everything changed again.

In 1952 the Supreme Court heard yet another case regarding cinema. In the case of Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the judges ruled that New York could not ban the commercial exhibition of a film because of sacrilegious content, as film was an artistic medium, protected by the 1st amendment.

The decision, more famously known as the “Miracle Decision,” made the 1915 ruling null and void. Films now had teeth to defend themselves individually against federal censorship, but this did not mean the end of the overseeing MPPDA.

By 1945, the new head of the organization, Eric Johnston, rebranded the MPPDA to what is known as today the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). With mounting pressure from the industry, the next head of the MPAA, Jack Valenti, did away with the production code in 1968.

Though the threat of Federal censorship had faded away, Hollywood was still wary of boycotts and state and city censorship boards, so Valenti implemented a voluntary rating system to replace the now defunct production code: “G” for “general audiences” ; “M” for “mature audiences” ; “R” for “restricted” ; and “X” for “adults only.” In 1970, “M” was changed to “GP” which meant “all ages admitted, but parental guidance suggested.” This was switched to “PG” in 1972.

At the suggestion of Stephen Spielberg, “PG-13” was introduced in 1984. And finally, when a lack of trademarks led to it being co-opted by the pornography industry, “X” was replaced with “NC-17,” in 1990. Originally, the MPAA provided no reasoning for the ratings of any individual film, but since 1990, a brief explanation has been attached to each rated piece.

To this day, it is the exhibitors who enforce the MPAA policies–there is no federal or state law that bars people who are underage from viewing any film. Instead, the MPAA is left to police its own terms, and producers voluntarily have their films rated (though all 7 major studios and most independent films that get distribution still go through this practice).

Over the years, filmmakers have levied criticisms at the perception that the MPAA has an innate policy of rating independent films more severely than they have rated studio films.

Along with complaints about seemingly arbitrary decisions regarding what can and can’t be shown in an R-rated film versus an NC-17-rated film, South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker have publicly lamented about their contemptuous dealings with the ratings board when working on their independent film, Orgasmo, compared to the relatively easy time they had in dealing with the organization for their studio film, South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut–films with content arguably similar in language, sexual overtones, and adult themes.

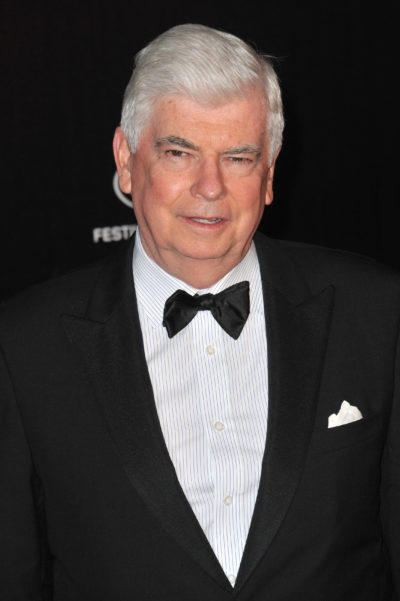

In 2004, the MPAA appointed former Senator Christopher Dodd as its new head, maintaining their appointment of leaders with political ties in Washington, largely because the MPAA plays a central role in lobbying for the interests of the film industry. This includes supporting such bills as the “Stop Online Piracy Act,” or “SOPA.” (Since SOPA was defeated, Dodd has urged a more friendly approach to dealing with online entertainment media.)

While the MPAA is still going strong, the same cannot be said for the National Legion of Decency. In 1966, it was rebranded as the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures.

It then became a part of the United States Catholic Conference, which was then incorporated into the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2001.

The rating newsletter stopped all together. The state and city boards of government censorship began the long process of shutting down in the latter half of the 20th century.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very interesting, and well researched piece.

For those of you who are interested in learning more about American film censorship, please take a look at a USC School of Cinematic Arts course syllabus on the subject. Therein you will find recommended films, and books further illustrating the topic:

http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:rOQCq_jyfroJ:web-app.usc.edu/soc/syllabus/20113/18185.doc+usc+ctcs+409&cd=3&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us