This is the fifth installment of our series “Reconstructing Kennedy.”

April 6, 1963

Scroll below for a decade of vintage ads

and Post art from 1953 to 1963.

(Click on images to expand.)

The decade began with a more promising look than the last three: The 1930s had started with the Depression, the 1940s with a world war, and the 1950s with the Korean conflict and the threat of nuclear war.

But the 1960s began with the election of a young, optimistic president who spoke of new opportunities. “Change is the law of life,” John F. Kennedy said, and in his inaugural address, he talked about “a new generation,” “a new alliance for progress,” “a new endeavor,” and “a new world of law.”

Such words were welcome to the younger generation, which had grown up in the shadow of war. They were eager for change, which began as Kennedy took office. But it did not begin with Kennedy alone. The changes that reshaped the country in the 1960s came from developments that started even before Kennedy took office.

In February 1960, months before Kennedy’s election, four black students sat down at a “whites-only” lunch counter and asked for service. When denied, they waited quietly and went home when the store closed. The next day, they were back with more students. It was not the first sit-in, but this one caught the attention of the press. The students eventually succeeded in pressuring the store to integrate its lunch counter, which encouraged black students in other college towns to stage their own sit-ins. The era of group protests for civil rights had begun.

On May 10, 1960, The New York Times ran a brief article announcing FDA approval for Enovid for use as an oral contraceptive. Freeing women from the fear of unwanted pregnancy, “the pill” was on its way to revolutionizing the sex life of the country.

On March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed an order establishing the Peace Corps. Within three months, it had received 11,000 applications from Americans. By 1963, over 7,000 Americans had put their lives on hold for two years to bring technical assistance and goodwill to underdeveloped nations. Today, almost a quarter-million Americans have served in the Corps.

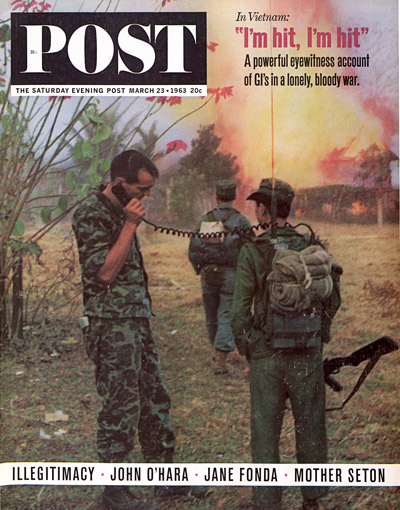

Two months later, President Kennedy ordered 400 Green Beret soldiers to South Vietnam. These “special advisors” were only intended to train the republic’s solders fighting communist guerillas. Kennedy hoped it would be a brief, successful intervention by the U.S. But by the next year, the number of U.S. troops had grown to 50,000. Before the decade was over, America had sent more than half a million soldiers to Vietnam and, coincidentally, created an immense anti-war movement at home.

In September of 1962, Rachel Carson published a book about chemical pesticides’ effects on wildlife. Her Silent Spring led to a Federal inquiry and new restrictions on the use of these chemicals. But the book can also be credited with helping start the modern environmental movement.

In 1963, Betty Friedan proposed writing an article about the unhappiness and discontent among American women. When no magazine accepted the article, she wrote a book on the subject, The Feminine Mystique. Many historians believe it launched the new wave of feminism, which would change the relations between the sexes in our country.

Few Americans could be faulted for not recognizing these early signs of massive change. It was easier to see changes closer to home. One of the most noticeable ways in which life was different in the 1960s was the manner in which many American could spend their free time.

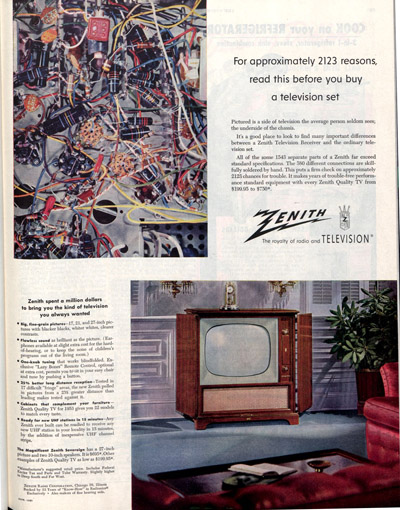

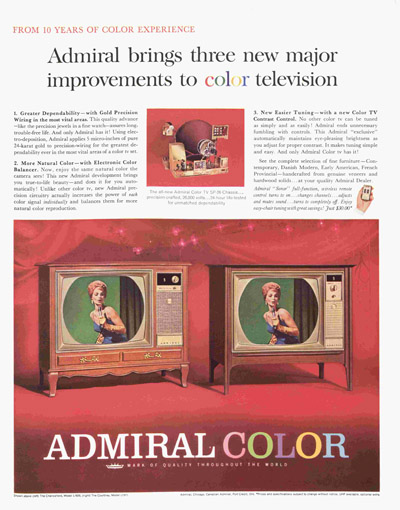

At the close of World War II, they had relied on radio and motion pictures for entertainment; network broadcasting of television shows was virtually nonexistent. Fifteen years later, Americans were spending five hours every night in front of their TV sets. Manufacturers were starting to push color sets, even though major networks didn’t fully switch to color broadcasting until 1967.

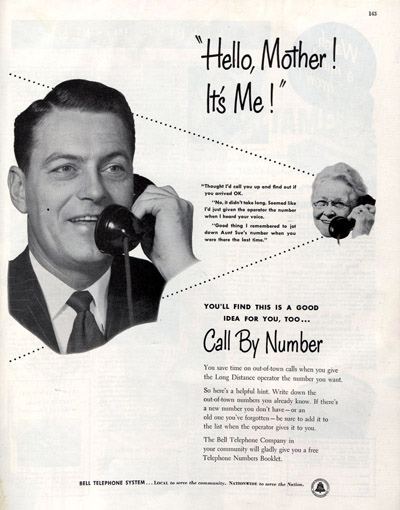

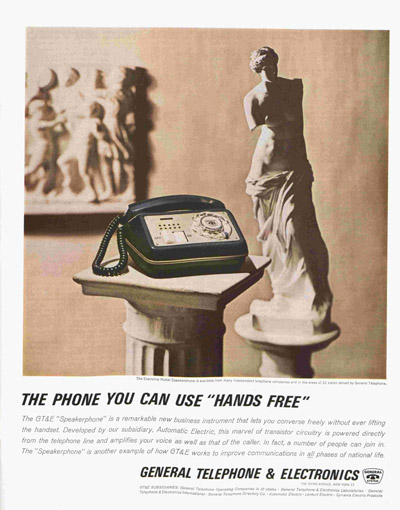

When they weren’t in front of the television, Americans were spending more time on the telephone. The modern phones of 1963 were portable (i.e., no longer fastened to the wall), used buttons instead of rotary dials, and even had speakers so you could talk on the phone with both hands.

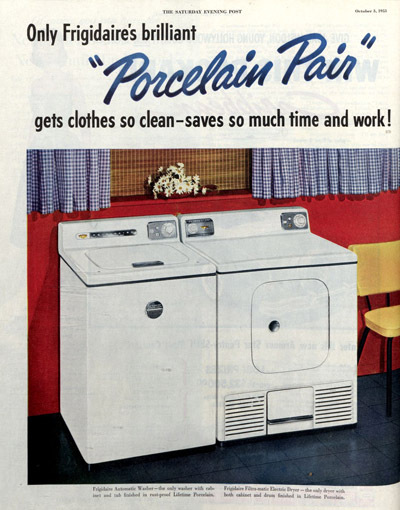

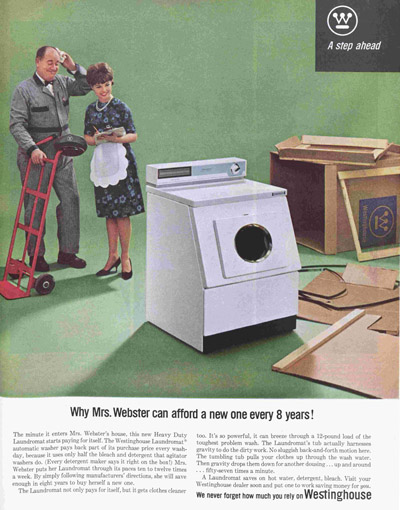

Most Americans knew little about the schools of modern design, but they could tell that their washing machine, which looked so up-to-date in 1953, now looked dated. The newer models were more compact, more efficient, and available in pink!

Frigidaire Washing Machine

General Electric Washing Machine

Westinghouse Washing Machine

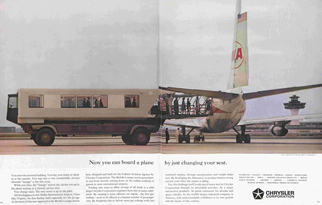

Transportation was also changing. Flying had once been a luxury only the rich could afford. Now, more and more Americans were crossing the country by air instead of driving the nation’s pre-interstate highway system. Between 1953 and 1963, the annual civilian air traffic rose from 8 million hours to 15 million.

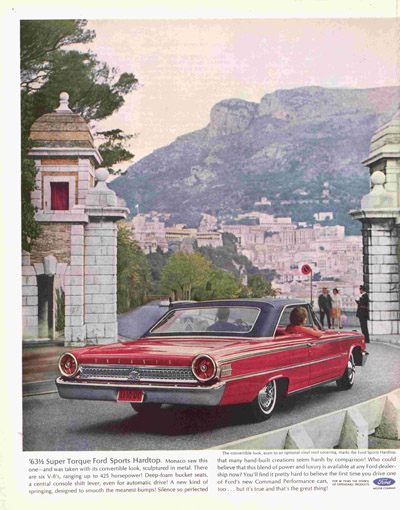

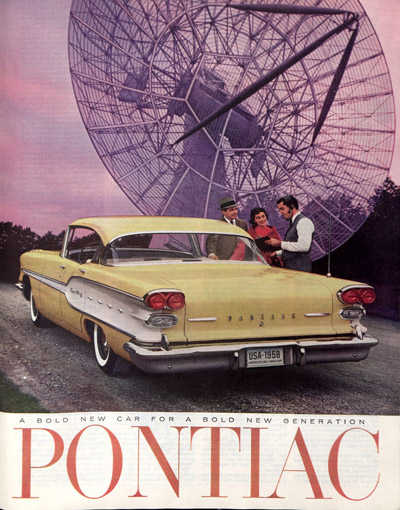

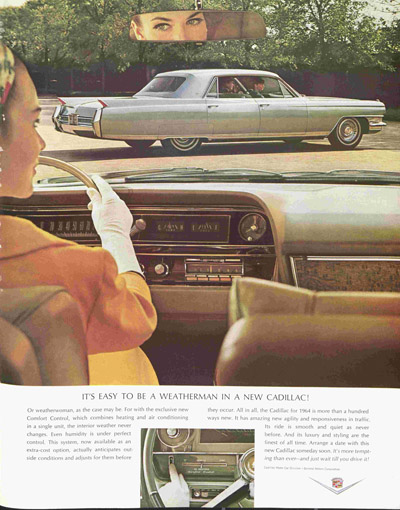

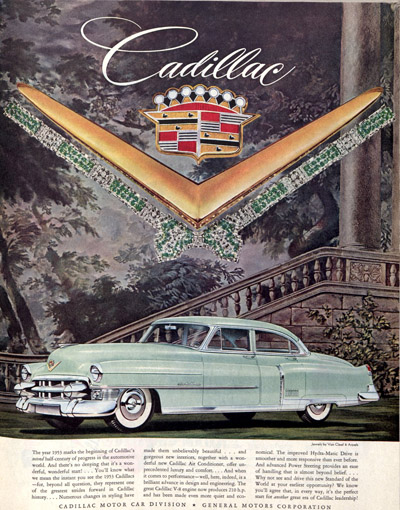

Meanwhile, 94 million American drivers were supporting the nation’s auto industry that turned out over 7 million cars every year. Anyone shopping for a new car in 1963 would have been struck by how much American auto design had changed over the years. The new cars seemed less enthralled with vast chrome grills. They were lower, sleeker, and more aerodynamic. They had lost the corpulent curves and, though still large, they were styled to reflect a modern idea of simple, straight-lined elegance that implied speed even when the car was standing still.

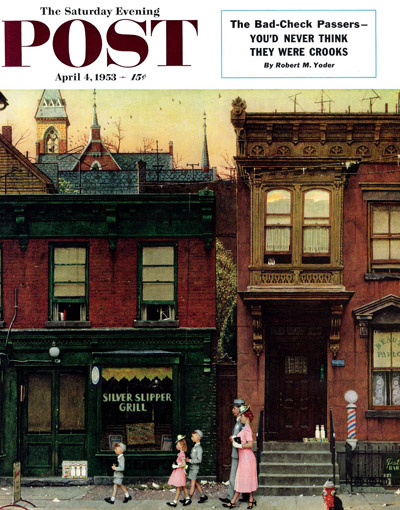

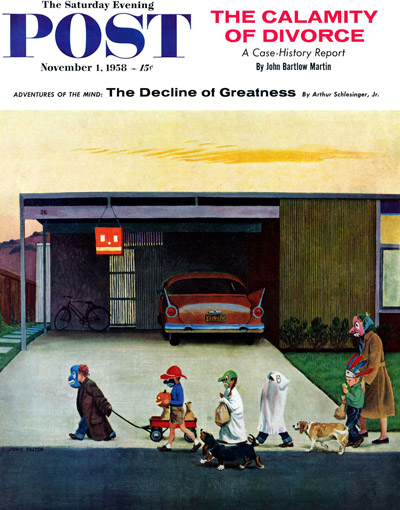

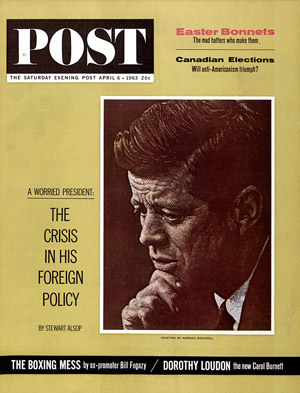

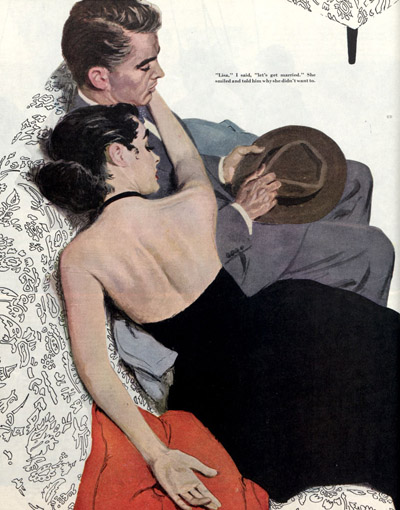

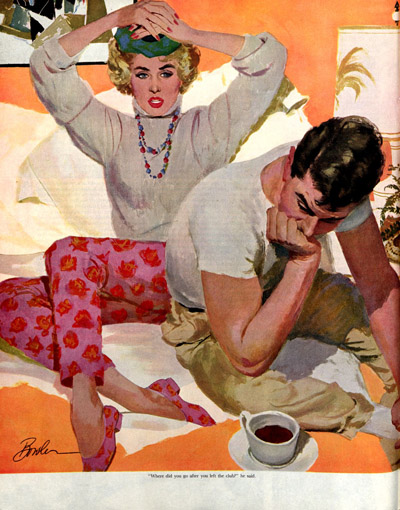

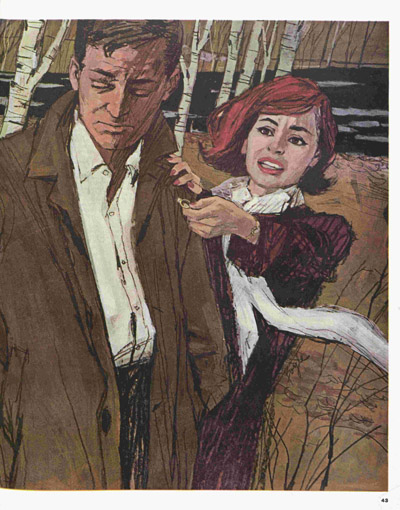

Over 6.5 million Americans would also have seen change in their weekly copies of the Post. Between 1953 and 1963, the illustration style of the magazine became more impressionistic. By 1963, the magazine had changed to meet Americans’ preference for photographic illustration. Most of the covers featured color photos instead of illustration, and many of the articles inside used full-page and color photography.

Once the Post had dictated popular tastes in American entertainment. Now it hurried to catch up with the popular tastes shaped by the new electronic media.

The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post

The Saturday Evening Post

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now