The president might have insisted that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” but he evidently forgot to check with his wife first. Eleanor was something of a nervous wreck on March 4, 1933, her first Inauguration Day as first lady. She stood, shivering and apprehensive, as Franklin leaned on their son James’ shoulder and walked deliberately from the East Portico of the Capitol out to the center of the inauguration platform, 146 daunting feet away. While his landmark “fear itself” speech took only 15 minutes, the ensuing parade stretched for six miles and several hours. “The crowds were so tremendous, and you felt that they would do anything — if only someone would tell them what to do,” Eleanor recalled. “It was very, very solemn, and a little terrifying.” The president wouldn’t budge until the last of the 40 marching bands had filed by, but she had to leave early to get back to the White House to greet the 1,000 guests invited for afternoon tea and sandwiches (though 3,000 actually showed up). Later that night, the woman who had dreaded dances and cotillions her entire life would leave Franklin behind again to attend the inaugural ball.

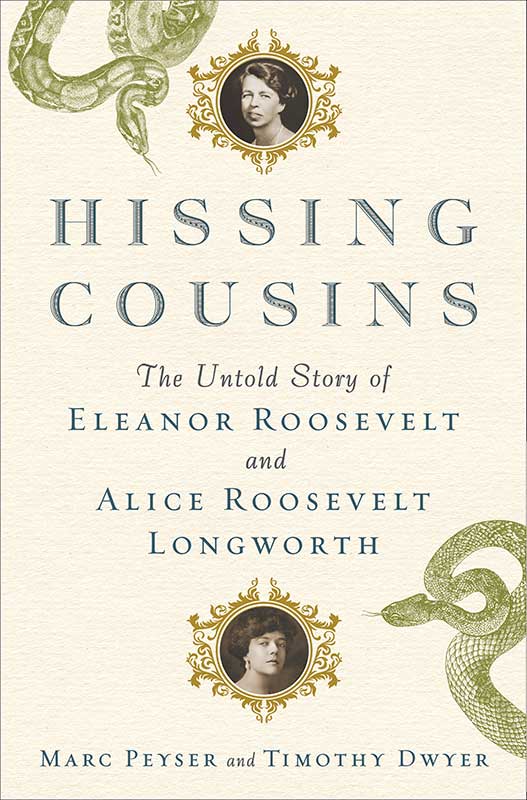

And that was the easy part of the day. A few hours earlier that same evening, she had endured the most fearsome event, when the extended Roosevelt family arrived to celebrate its latest White House triumph. There were 75 of them in all for a buffet dinner, and not a drop to drink. (Prohibition wasn’t repealed until December.) The invitation list was drawn up by Sara Delano Roosevelt, FDR’s mother, who sat near her Franklin in the small drawing room, swollen with pride and expensive jewelry, waiting to welcome the guests. Eleanor discarded the usual first-lady protocol and greeted the visitors herself at the door, among them cousins Teddy and Helen Robinson and Archie Roosevelt from her side; cousins Laura and Lyman Delano and Aunt Kassie Collier from his. And then came Cousin Alice.

At first, no one knew exactly how to react. After all, this was a party for a victory Alice had tried to snuff out like a kitchen fire. The indomitable Sara chatted with her amiably; Alice had the good sense to limit her conversation to praising the current President Roosevelt, as opposed to the previous one (aka Alice’s father). Then she walked over to Eleanor. Alice thought her cousin could use a few pointers. “You’ll be able to learn after a while how to handle affairs like this,” she told Eleanor, glancing around the roomful of their collective kin. “I’ll help you if you like.” Not everyone appreciated Alice’s condescending brand of goodwill. “Mother expressed her thanks, her nervousness mounting under her cousin’s patronage,” said Eleanor and Franklin’s son Elliott. “Almost two years of widowhood had done nothing to curb [Alice’s] style or her irresistible compulsion to lord it over Mother.”

Alice’s lifetime claim on the White House was as strong as ever in 1933. She didn’t only drop by on Franklin’s first day. She had also been there the day before to visit the previous residents — the Hoovers. Alice said she wanted to take Paulina, her 8-year-old daughter, over to say good-bye, but there was clearly a dose of morbid curiosity in her motivation. “They looked like figures from waxworks, they looked so unalive. Poor, stiff, bruised, wounded,” she said. “That was the third of March. The next night — dinner at Franklin’s! Dinner at the White House! Riots of pleasure! All of us there, all of us having a good time. It couldn’t have been a more incredible contrast.”

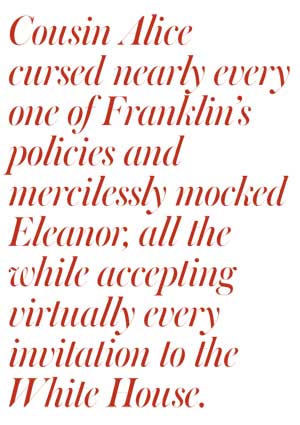

Alice must have been in a very small circle of people in history who were invited to visit the outgoing president on his last day in office and the man who defeated him on his first. The fact that she showed up to celebrate with the extended family wasn’t entirely shocking, though given her rabid support for the Republican ticket it was a little like a player from the losing Super Bowl team dropping by the winners’ locker room to guzzle champagne. In the years that followed, what surprised and puzzled onlookers was that Alice kept coming back. Faced with the grim reality of now being an “out-of-season” Roosevelt (a phrase coined by Alexander Woollcott), she had two options for dealing with the rise of her Hyde Park relatives: make peace with them (as her brother Kermit did), or take a vow of ice-cold hostility (her brother Ted’s route). Naturally she chose both options. She cursed nearly every one of Franklin’s policies and mercilessly mocked Eleanor, all the while accepting virtually every invitation to the White House. The more belligerent members of her immediate family were disgusted by her willingness to associate with the White House usurpers. “I could not help feeling that it was like behaving in like fashion to an enemy during a war,” said Alice’s devoted brother Ted, who rarely disagreed with her on anything. “More so, for enemies generally only fight for territory, trade, or some material possessions. These are fighting us for our form of government, our liberties, the future of our children.”

For her part, Eleanor had expected to follow the same below-the-radar path as the previous first ladies. “I knew what traditionally should lie before me,” she said. “I had watched Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and had seen what it meant to be the wife of the president, and I cannot say I was pleased by the prospect.” Her enforced vow of monotony lasted exactly two days. On the Monday after the inauguration, Eleanor conducted a press conference in the Red Room. That was noteworthy on its own; no first lady had ever held her own White House press conference before. Eleanor also added a twist: she only allowed female reporters to attend. It was her form of affirmative action, a way to underscore the disadvantages women faced in most professions, including the media. The first conference attracted 35 female reporters, some of whom had to sit on the floor because there weren’t enough chairs. Eleanor arrived carrying a box of candied fruit and passed it around as if she were hosting a neighborhood bridge party. There was a decidedly clubby feeling at her conferences. She focused on topics she felt would interest women and pledged not to answer anything blatantly political, which she insisted was the president’s realm. When she seemed to stray too close to hot-button territory, it was the women reporters who would sometimes caution her by yelling out, “Oh, Mrs. Roosevelt, you’d better put that off the record!” The female press corps developed a strong (and some would say unprofessional) sense of loyalty, even devotion, to her.

It’s no wonder that Edward Bok, TR’s old friend and the editor of the Ladies Home Journal, commissioned Alice to write an article called “The Ideal Qualifications for a President’s Wife.” Journalistically, it was inspired casting. After all, who better to opine on Washington tradition — and how to break it — than Princess Alice. She took a poke or two at her cousin, but she wrote in a sort of invisible ink, focusing on Eleanor’s means — her noblesse oblige and obsession with saving the world — rather than her actual policy choices. If Eleanor was overstepping her boundaries as the president’s wife, Alice certainly wasn’t going to say so directly, even as she reminded readers that the first lady was still fair game. “There is always the possibility,” she warned, “that people will say, ‘We didn’t elect her. What is she horning in for?’”

Eleanor horned in because, like her uncle Ted, she knew the value of a bully pulpit. A meeting with the first lady, or just her brief presence at an event, could shine a light on an issue or problem she cared about. In addition to her own priorities, she continued her now-familiar role as her husband’s stand-in. In New York, as the wife of a governor in a wheelchair, she was obligated to travel from one corner of the state to the other; as the wife of a president in a wheelchair, she had to do it on a national scale. In her first year as first lady, she logged 38,000 miles (and even more the next). She was the first first lady to travel by airplane, though she was perfectly happy using less stylish modes of transportation. She frequently spent the night on a train, sometimes sleeping in her seat if a sleeper car wasn’t available.

In November 1933, she made the cover of Time magazine (more than six years after Alice earned that honor). The apt headline was “Eleanor Everywhere.” The Time cover had been published to coincide with the release of Eleanor’s book of essays called It’s Up to the Women, an odd mix of platitudes (“For every normal human being, fresh air is essential”) and impassioned arguments about the role of women in the country and the world. She wasn’t the only Roosevelt moonlighting as an author. The same week that Eleanor’s book was released, Alice published her long-awaited autobiography, Crowded Hours (a favorite phrase of her father’s). Derived in large part from a series of articles Alice had written for the Ladies’ Home Journal, Crowded Hours was a fairly bloodless political memoir. Still, the book sold well, in large part because Alice had said so little for the record over her 30-plus years of celebrity. Crowded Hours was at the top of the nonfiction best-seller lists for every city east of the Mississippi on November 13, 1933. That was the week Eleanor’s book hit the stands. It’s Up to the Women only made the list in Washington, where it beat out Crowded Hours for the top spot.

As it turned out, the cousins’ books were only an introduction to what became a long-running media sparring match. The next round, ironically, was touched off by Will Rogers, world-famous actor, writer, vaudevillian, and wit. Rogers was one of a handful of prominent people who was a friend equally to Alice and to Eleanor. In August 1935, the 55-year-old Rogers was touring Alaska with the famed aviator Wiley Post when their plane crashed on takeoff, killing them both. His column, Will Rogers Says, had been a fixture in American newspapers for 13 years, read daily by 40 million people. Suddenly the McNaught Syndicate needed another pithy, informed, well-known writer to fill Rogers’ space. McNaught’s founder, V.V. McNitt, thought Princess Alice was just the woman for the job. The trouble was, as much as Alice admired writers, she didn’t enjoy writing herself. The drudgery didn’t appeal to her, though she’d never say that in so many words. “I shall never write another book,” she’d later joke. “My vocabulary is too limited.” But McNitt pursued her for months, and he finally prevailed. Alice’s appeal was strong enough that more than 75 newspapers bought her column sight unseen.

What Alice Thinks debuted in January 1936, and just as McNaught had hoped, she zeroed in on all aspects of the New Deal. But while Will Rogers had been a master at bringing the high-and-mighty down to the level of the average Joe, Alice was such a deep Capitol Hill insider that she was practically entombed. In What Alice Thinks, she would launch into an attack on boondoggles at Passamaquoddy or the persecution of General Hagood, all with the assumption that her readers were as in the know as the guests at her A-list dinner parties. Less than two months into her run many readers were wondering just what was Alice thinking?

What Alice Thinks looked all the more ponderous next to a new column by another celebrated Washington woman: Eleanor. When word spread that a column from Alice was in the offing, the editors at the United Feature Syndicate were eager for a column by the first lady that could compete. But they weren’t sure that the multitasking and peripatetic first lady could pull it off. At the time of its launch, only 25 papers bought the column, which was called My Day.

The early columns were chatty slices of the first lady’s daily life, both in her official capacity as a White House hostess and as a mother and grandmother. But what made My Day stand out was the context. Many of her mundane stories might sound unexceptional in the social-media era, but no one had ever pulled the curtain back like that before on a world so close to the president. Discovering that the first lady of the United States had a lot in common with the average housewife was a revelation.

While Alice’s lens was tightly focused on Washington, politics, and the dance of legislation, Eleanor’s was a broader and softer report on the people and events that whirled through her active life. If Alice spent one day squawking about cabinet secretaries fighting for their share of WPA funds, on that same day Eleanor might recount her trip to the District of Columbia Training School for Delinquent Girls. Alice was the cynic to Eleanor’s idealist, the same roles they had played since they were teenagers. “I am trying terribly hard to be impartial and malevolent at the same time,” she told Newsweek when her column debuted, “but when I think of Frank and Eleanor in the White House I could grind my teeth to powder and blow them out my nose.”

Alice was perhaps the only woman on the planet who referred to the president as Frank. Naturally, she was more formal to his face. “I called him ‘Franklin,’” she said. “He used to wince, as if he’d prefer me to call him ‘Mr. President.’ That would annoy him, you see. But we had a very good time together.” Which is to say, she had a good time needling him, and he tolerated — and maybe even appreciated — her outrageous sense of humor.

Eleanor found herself caught in her cousin’s web, too, thanks to her cousin’s gift for mimicry. With her teeth thrust out, her jaw tucked in, and her voice ratcheted to a quivering upper register, Alice’s take on Eleanor came across as something like a talking horse just out of a proper British finishing school. Her act started as a cocktail party trick, but soon became infamous enough that Washington gossip columnists would report whenever Alice added new features to it. Marion Dickerman recalled being at a White House luncheon when Eleanor asked Alice an awkward question: “Alice, why don’t you give one of your impersonations of me now.” Dickerman recalled that the always self-assured Alice seemed, briefly, uneasy before performing the routine that had been generating guffaws at parties across the capital. Eleanor obligingly laughed along. If she was hurt, she didn’t give Alice the satisfaction of responding. “The most helpful criticism I ever received,” Eleanor wrote, “was a takeoff of me on the radio done by my cousin, Alice Longworth. She did it for me one afternoon and I could not help being amused and realizing that it was a truthful picture, and that I had many things to correct.”

Not surprisingly, the Washington chattering class started predicting Alice’s exile from the White House once and for all. The story became such a hot topic that the reporters at one of Eleanor’s weekly press conferences asked if it were true. Eleanor denied it categorically. But Alice herself told a different story. Years later, she insisted that Eleanor dropped a series of hints to stay away:

“When Eleanor came to the White House, she said to me, ‘You are always welcome here but you must never feel that you have to come.’ So, [I went] with great alacrity and enthusiasm and had a lovely, malicious time. Then a little while later I had another communication from Eleanor. ‘I’m told that you are bored at coming to the White House, and I never want you to be that, so …’ So I wrote her a very cheerful reply, saying, ‘How disagreeable people are, trying to make more trouble than there already is between us, and of course I love coming to the White House. It couldn’t be more fun and I have always enjoyed myself immensely, etc., etc.’ Needless to say, she never asked me there again.”

It was true that Alice could test the limits of her cousins’ tolerance. When James Roosevelt proposed that his father appoint Alice to some unnamed government commission, FDR’s reply, “which I shall censor somewhat,” Eleanor told a friend, “was: ‘I don’t want anything to do with that woman!’” But the invitations to the White House kept coming. Several newspapers reported that Franklin and Eleanor invited Alice to the White House on February 12, 1934. That was Alice’s 50th birthday, and Eleanor knew that her cousin would enjoy celebrating the landmark at her old home.

It had always been Eleanor’s nature to try to smooth over disagreements that might rattle family harmony. But she could easily have abandoned her peacekeeper role. After all, she was the one now sitting in the White House. She was the one whose column had become a success nationwide, appearing in 62 papers by 1938. On the other hand, by June 1937 Alice’s career as a columnist was put to bed, 18 months after it began.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now