It seemed like a great idea at the time.

Having read about an automobile race in France, H.H. Kohlsaat decided he’d host America’s first auto race in Chicago. The year was 1895 and automobiles were still a great novelty. Kohlsaat, who owned the Chicago Times Herald, planned to exploit the growing interest in motoring by sponsoring a 54-mile race from downtown Chicago to Evanston, Illinois, and back. It would be open to all qualifying vehicles, foreign or domestic, powered by gas, electricity, or steam. The top prize would be $2,000 (the equivalent of over $50,000 today).

To draw a big holiday crowd, he set the race date for the Fourth of July 1895.

He quickly learned this was too soon for the competitors. Applicants begged Kohlsaat to postpone the race so they could get their vehicles ready for the competition.

So Kohlsaat pushed the race back to Labor Day. As that date drew near, the contestants pleaded for more time.

In the end, Kohlsaat pushed the date back to Thanksgiving Day, November 28.

He hoped that fair weather would hold for the race, but the night before Thanksgiving, a storm blew into town and buried Chicago streets in snow. High winds followed, blowing snowdrifts across racecourse streets.

Only six cars made it to the starting line in Jackson Park that morning. At 8:55 a.m., a small, shivering crowd watched the first vehicle set off. It was the only gas-powered American car in the contest and had been built by brothers Charles and Frank Duryea. The other three gas vehicles were all German machines built by Karl Benz, one representing the De La Verne Refrigerator Machine Company, one representing Macy’s Department Store in New York, and the last driven by Oscar Mueller of Decatur, Illinois, who proved a tough adversary.

The last two entries were electric models, a Sturges Electric and Morris and Salom’s Electrobat. No steam models competed.

After the cars disappeared, the crowd dispersed. It was 30 degrees and windy at the lakeside. With the vehicles expected to travel at just 5 mph, there would be nothing to see for the next 10 hours.

The vehicles struggled up Lake Shore Drive fighting wind and snowdrifts. As they passed Lincoln Park, they were suddenly greeted by cheers from a crowd of thousands. These weren’t race fans, but attendees at the football game between the University of Chicago and University of Michigan, who noticed the horseless carriages slowly working their way up the street. Shortly afterward, as Frank Duryea crossed the Rush Street Bridge, the steering arm on his vehicle snapped. He managed to get his vehicle to a blacksmith’s shop, where the arm was repaired, but the delay put him an hour behind the leading Benz car.

Years later, when Kohlsaat gave his account of the race in the Post, he wrote that early that on Thanksgiving afternoon “a large number of people gathered near the [Evanston] Industrial School and received the first comers with cheers. The Macy machine was then slightly in the lead.” Just two blocks beyond, though, Frank Duryea came up on the leader. “In accordance to the rules of the contest,” Kohlsaat wrote, the Macy Benz pulled to one side.

The driver of the Macy Benz tried to close Duryea’s lengthening lead, but late in the afternoon, Macy’s driver ran into a sleigh that had overturned in the street. He was able to extricate the car and resume driving, but he soon ran into a horse-drawn hackney cab, which damaged the car’s steering. The driver managed to roll the car in-between the trolley car tracks and drive between the tracks to next checkpoint. Mechanics spent 80 minutes putting the Benz back in running order. But by 6:15, the darkening sky and cold winds were too discouraging. The Macy Benz vehicle dropped out of the race.

This left just Duryea and another Benz, driven by Oscar Mueller.

Duryea had now been driving for nine hours. He was experiencing trouble with his ignition, not to mention the snowdrifts. In addition, he’d taken a wrong turn that added several miles to his route. But he was still ahead of Mueller, who was facing even greater difficulties.

Before starting, Mueller had decided he would not just carry a referee, like all entrants, but an extra passenger as well. After spending the day in the back of the car, huddled against the freezing winds, the passenger was overcome by the cold. He was lifted out of the car and carried off for medical attention in a sleigh. Mueller kept driving, but he, too, was losing consciousness.

By 6:30 p.m., Duryea was getting close to the finish line. Kohlsaat wrote, “Lacking spectators, except here and there a solitary workman on his way home … the men on the motor gave vent to war whoops, cheers, cat calls, and other manifestations of joy over the victory they were winning.”

At 7:18 p.m., Frank Duryea crossed the finish line. He’d taken 10 hours and 23 minutes to travel 52.4 miles.

Almost two hours later, Mueller’s Benz came in sight, but now the referee was driving. In one hand, he held the steering tiller and, in the other, held up Mueller, who’d collapsed from the cold.

The first automobile race was over.

The next automobile race was held, more sensibly, on Memorial Day.

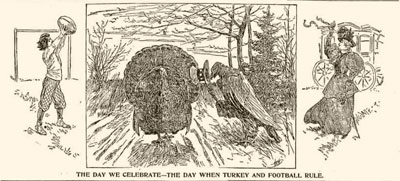

Not surprising, Chicago’s Thanksgiving Day race never became a holiday tradition. Chicagoans weren’t afraid to spend hours standing in the cold for a public event. But even as early as 1895, the holiday already established its cold-weather sport. As the Chicago Tribune declared on its front page that day, Thanksgiving was, “the day we celebrate — the day when football and turkey rule.”

Kohlsaat’s account doesn’t use the term “automobile.” As he explains, “There was considerable opposition to calling the horseless carriage ‘automobile,’ as the name was too Frenchy, so The Times Herald offered $500 for a name, and ‘motocycle’ was awarded the prize.”

That’s motocycle, without an r.

Years later, Duryea recalled his early days of inventing the automobile, and his early racing days. You can read his article “It Doesn’t Pay to Pioneer,” originally published in 1931, in the Post’s latest special issue: Automobiles in America!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now