Originally published March 18, 1950

The clerk of the court took a good look at the tall brown-skinned woman with the head rag on. She sat on the third bench back with a husky officer beside her.

“The People versus Laura Lee Kimble!”

The policeman nudged the woman to get to her feet and led her up to the broad rail. She stood there, looking straight ahead. The hostility in the room reached her without her seeking to find it.

Unpleasant things were ahead of Laura Lee Kimble, but she was ready for this moment. It might be the electric chair or the rest of her life in some big lonesome jail house, or even torn to pieces by a mob, but she had passed three long weeks in jail. She had come to the place where she could turn her face to the wall and feel neither fear nor anguish. So this here so-called trial was nothing to her but a form and a fashion and an outside show to the world. She could stand apart and look on calmly. She stood erect and looked up at the judge.

“Charged with felonious and aggravated assault. Mayhem. Premeditated attempted murder on the person of one Clement Beasley. Obscene and abusive language. Laura Lee Kimble, how do you plead?”

Laura Lee was so fascinated by the long-named things that they were accusing her of that she stood there tasting over the words. Lawdy me! she mused inside herself. Look like I done every crime excepting habeas corpus and stealing a mule.

“Answer the clerk!” The officer nudged Laura Lee. “Tell him how you plead.”

“Plead? Don’t reckon I make out just what you all mean by that.” She looked from face to face and at last up at the judge, with bewilderment in her eyes. She found him looking her over studiously.

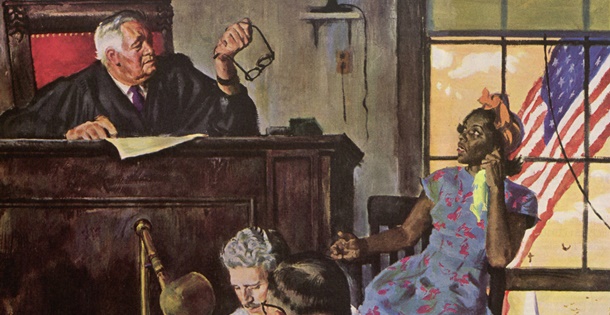

The judge understood the look in her face, but he did not interfere so promptly as he ordinarily would have. This was the man-killing bear cat of a woman that he had heard so much about. Though spare of fat, she was built strongly enough, all right. An odd Negro type. Gray-green eyes, large and striking, looking out of a chestnut-brown face. A great abundance of almost straight hair only partially hidden by the high-knotted colored kerchief about her head. Somehow this woman did not look fierce to him at all. Yet she had beaten a man within an inch of his life. Here was a riddle to solve. With the proud, erect way she held herself, she might be some savage queen. The shabby housedress she had on detracted nothing from this impression. She was a challenge to him somehow or other.

“Perhaps you don’t understand what the clerk means, Laura,” the judge found himself saying to her in a gentle voice. “He wants you to say whether you are guilty of the charges or not.”

“Oh, I didn’t know. Didn’t even know if he was talking to me or not. Much obliged to you, sir.” Laura Lee sent His Honor a shy smile. “‘Deed I don’t know if I’m guilty or not. I hit the man after he hit me, to be sure, Mister Judge, but if I’m guilty I don’t know for sure. All them big words and all.”

The clerk shook his head in exasperation and quickly wrote something down. Laura Lee turned her head and saw the man on the hospital cot swaddled all up in bandage rags. Yes, that was the very man who caused her to be here where she was.

“All right, Laura Lee,” the judge said. “You can take your seat now until you are called on.”

The prosecutor looked a question at the judge and said, “We can proceed.” The judge nodded, then halted things as he looked down at Laura Lee.

“The defendant seems to have no lawyer to represent her.” Now he leaned forward and spoke to Laura Lee directly. “If you have no money to hire yourself a lawyer to look out for your interests, the court will appoint one for you.”

There was a pause, during which Laura Lee covered a lot of ground. Then she smiled faintly at the judge and answered him. “Naw sir, I thank you, Mister Judge. Not to turn you no short answer, but I don’t reckon it would do me a bit of good. I’m mighty much obliged to you just the same.”

The implications penetrated instantly and the judge flushed. This unlettered woman had called up something that he had not thought about for quite some time. The campus of the University of Virginia and himself as a very young man there, filled with a reverence for his profession amounting to an almost holy dedication. His fascination and awe as a professor traced the more than two thousand years of growth of the concepts of human rights and justice. That brought him to his greatest hero, John Marshall, and his inner resolve to follow in the great man’s steps, and even add to interpretations of human rights if his abilities allowed. No, he had not thought about all this for quite some time. The judge flushed slowly and deeply.

Below him there, the prosecutor was moving swiftly, but somehow his brisk cynicism offended the judge. He heard twelve names called, and just like that the jury box was filled and sworn in.

Rapidly now, witnesses took the stand, and their testimony was all damaging to Laura Lee. The doctor who told how terribly Clement Beasley had been hurt. Left arm broken above the elbow, compound fracture of the forearm, two ribs cracked, concussion of the brain and various internal injuries. Two neighbors who had heard the commotion and arrived before the house in time to see Laura Lee fling the plaintiff over the gate into the street. The six arresting officers all got up and had their say, and it was very bad for Laura Lee. A two-legged she-devil no less.

Clement Beasley was borne from his cot to the witness stand, and he made things look a hundred times blacker. His very appearance aroused a bumble of pity, and anger against the defendant. The judge had to demand quiet repeatedly. Beasley’s testimony blew strongly on the hot coals.

His story was that he had come in conflict with this defendant by loaning a sizable sum of money to her employer. The money was to be repaid at his office. When the date was long past due, he had gone to the house near the river, just off Riverside Drive, to inquire why Mrs. Clairborne had not paid him, nor even come to see him and explain. Imagine his shock when he wormed it out of the defendant that Mrs. Clairborne had left Jacksonville. Further, he detected evidence that the defendant was packing up the things in the house. The loan had been made, six hundred dollars, on the furnishings of the entire house. He had doubted that the furnishings were worth enough for the amount loaned, but he had wanted to be generous to a widow lady. Seeing the defendant packing away the silver, he was naturally alarmed, and the next morning went to the house with a moving van to seize the furniture and protect the loan. The defendant, surprised, attacked him as soon as he appeared at the front door, injured him as he was, and would have killed him if help had not arrived in time.

Laura Lee was no longer a spectator at her own trial. Now she was in a flaming rage. She would have leaped to her feet as the man pictured Miz’ Celestine as a cheat and a crook, and again as he sat up there and calmly lied about the worth of the furniture. All of those wonderful antiques, this man making out that they did not equal his minching six hundred dollars! That lie was a sin and a shame! The People was a meddlesome and unfriendly passel and had no use for the truth. It brought back to her in a taunting way what her husband, Tom, had told her over and over again. This world had no use for the love and friending that she was ever trying to give.

It looked now that Tom could be right. Even Miz’ Celestine had turnt her back on her. She was here in this place, the house of The People, all by herself. She had ever disbelieved Tom and had to get to be forty-nine before she found out the truth. Well, just as the old folks said, “It’s never too long for a bull frog to wear a stiff-bosom shirt. He’s bound to get it dirtied some time or other.”

“You have testified,” Laura Lee heard the judge talking, “that you came in contact with the defendant through a loan to Mrs. J. Stuart Clairborne, her employer, did you not?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” Beasley answered promptly and glibly.

“That being true, the court cannot understand why that note was not offered in evidence.”

Beasley glanced quickly at the prosecutor and lowered his eyes. “I — I just didn’t see why it was necessary, Your Honor. I have it, but — ”

“It is not only pertinent, it is of the utmost importance to this case. I order it sent for immediately and placed in evidence.”

The tall, lean, black-haired prosecutor hurled a surprised and betrayed look at the bench, then, after a pause, said in a flat voice, “The State rests.”

What was in the atmosphere crawled all over Laura Lee like reptiles. The silence shouted that her goose was cooked. But even if the sentence was death, she didn’t mind. Celestine Beaufort Clairborne had failed her. Her husband and all her folks had gone on before. What was there to be so happy to live for any more? She had writ that letter to Miz’ Celestine the very first day that she had been placed in jail. Three weeks had gone by on their rusty ankles, and never one word from her Celestine. Laura Lee choked back a sob and gritted her teeth. You had to bear what was placed on your back for you to tote.

“Laura Lee Kimble,” the judge was saying, “you are charged with serious felonies, and the law must take its course according to the evidence. You refused the lawyer that the court offered to provide for you, and that was a mistake on your part. However, you have a right to be sworn and tell the jury your side of the story. Tell them anything that might help you, so long as you tell the truth.”

Laura Lee made no move to get to her feet and nearly a minute passed. Then the judge leaned forward.

“Believe it or not, Laura Lee, this is a court of law. It is needful to hear both sides of every question before the court can reach a conclusion and know what to do. Now, you don’t strike me as a person that is unobliging at all. I believe if you knew you would be helping me out a great deal by telling your side of the story, you would do it.”

Involuntarily Laura Lee smiled. She stood up. “Yes, sir, Mister Judge. If I can be of some help to you, I sure will. And I thank you for asking me.”

Being duly sworn, Laura Lee sat in the chair to face the jury as she had been told to do. “You jury-gentlemens, they asked me if I was guilty or no, and I still don’t know whether I is or not. I am a unlearnt woman and common-clad. It don’t surprise me to find out I’m ignorant about a whole heap of things. I ain’t never rubbed the hair off of my head against no college walls and schooled out nowhere at all. All I’m able to do is to tell you gentlemens how it was and then you can tell me if I’m guilty or no.

“I would not wish to set up here and lie and make out that I never hit this plaintive back. Gentlemens, I ain’t had no malice in my heart against the plaintive. I seen him only one time before he come there and commenced that fracas with me. That was three months ago, the day after Tom, my husband, died. Miz’ Celestine called up the funeral home and they come and got Tom to fix him up so we could take him back to Georgia to lay him to rest. That’s where us all come from, Chatham County — Savannah, that is.

“Then now, Miz’ Celestine done something I have never knowed her to do be-fore. She put on her things and went off from home without letting me know where she was bound for. She come back afterwhile with this plaintive, which I had never seen before in all my horned days. I glimpsed him good from the kitchen where I was at, walking all over the dining room and the living room with Miz’ Celestine and looking at things, but they was talking sort of low like, and I couldn’t make out a word what they was talking about. I figgered that Miz’ Celestine must of been kind of beside herself, showing somebody look like this plaintive all her fine things like that. Her things is fine and very scarce old antiques, and I know that she have been offered vast sums of money for ‘em, but she would never agree to part with none. Things that been handed down in both the Beaufort and the Clairborne families from way back. That little old minching six hundred dollars that the plaintive mentioned wouldn’t even be worth one piece of her things, not to mention her silver. After a while they went off and when Miz’ Celestine come back, she told me that everything had been taken care of and she had the tickets to Savannah in her purse.

“Bright and soon next morning we boarded the train for Savannah to bury Tom. Miz’ Celestine done even more than she had promised Tom. She took him back like she had promised, so that he could be buried in our family lot, and he was covered with flowers, and his church and his lodges turned out with him, and he was put away like some big mogul of a king. Miz’ Celestine was there sitting right along by my side all the time. Then me and Miz’ Celestine come on back down here to Jacksonville by ourselves.

“And Mrs. Clairborne didn’t run off to keep from paying nobody. She’s a Clairborne, and before that, she was born a Beaufort. They don’t owe nobody, and they don’t run away. That ain’t the kind of raising they gets. Miz’ Clairborne’s got money of her own, and lives off of the interest which she receives regular every six months. She went off down there to Miami Beach to sort of refresh herself and rest up her nerves. What with being off down here in Florida, away from all the folks she used to know, for three whole years, and cooped up there in her house, and remembering her dear husband being dead, and now Tom gone, and nobody left of the old family around excepting her and me, she was nervous and peaked like. It wasn’t her, it was me that put her up to going off down there for a couple of months so maybe she would come back to herself. She never cheeped to me about borrowing no money from nobody, and I sure wasn’t packing nothing up to move off when this plaintive come to the door. I was just gleaming up the silver to kill time whilst I was there by myself.

“And, gentlemens, I never tackled the plaintive just as soon as he mounted the porch like he said. The day before that, he had come there and asked-ed me if Miz’ Clairborne was at home. I told him no, and then he asked-ed me just when I expected her back. I told him she was down at Miami Beach, and got the letter that she had sent me so he could get her right address. He thanked me and went off. Then the next morning, here he was back with a great big moving wagon, rapped on the door and didn’t use a bit of manners and politeness this time. Without even a ‘Good morning’ he says for me to git out of his way because he come to haul off all the furniture and things in the house and he is short for time.

“You jury-gentlemens, I told him in the nicest way that I knowed how that he must of been crazy. Miz’ Celestine was off from home and she had left me there as a kind of guardeen to look after her house and things, and I sure couldn’t so handy leave nobody touch a thing in Mrs. Clairborne’s house unlessen she was there and said so.

“He just looked at me like I was something that the buzzards laid and the sun hatched out, and told me to move out of his way so he could come on in and get his property. I propped myself and braced one arm across the doorway to bar him out, reckoning he would have manners enough to go on off. But, no! He flew just as hot as Tucker when the mule kicked his mammy and begun to cuss and doublecuss me, and call me all out of my name, something nobody had never done be-fore in all my horned days. I took it to keep from tearing up peace and agreement. Then he balled up his fistes and demanded me to move ‘cause he was coming in.

“‘Aw, naw you aint,’ I told him. You might think that you’s going to grow horns, but I’m here to tell you you’ll die butt-headed.’”

His mouth slewed one-sided and he hauled off and hit me in my chest with his fist two times. Hollered that nothing in the drugstore would kill me no quicker than he would if I didn’t git out of his way. I didn’t, and then he upped and kicked me.

“I jumped as salty as the ‘gator when the pond went dry. I stretched out my arm and he hit the floor on a prone. Then, that truck with the two men on it took off from there in a big hurry. All I did next was to grab him by his heels and frail the pillar of the porch with him a few times. I let him go, but he just laid there like a log.

“‘Don’t you lay there, making out you’s dead, sir!’ I told him. ‘Git up from there, even if you is dead, and git on off this place!’

“The contrary scamp laid right there, so I reached down and muscled him up on acrost my shoulder and toted him to the gate, and heaved him’ over the fence out into the street. None of my business what become of him and his dirty mouth after that.

“I figgered I done right not to leave him come in there and haul off Miz’ Celestine’s things which she had left there under my trust and care. But Tom, my husband, would have said I was wrong for taking too much on myself. Tom claimed that he ever loved me harder than the thunder could bump a stump, but I had one habit that he ever wished he could break me of. Claimed that I always placed other folks’s cares in front of my own, and more expecially Miz’ Celestine. Said that I made out of myself a wishbone shining in the sun. Just something for folks to come along and pick up and rub and pull and get their wishes and good luck on. Never looked out for nothing for my ownself.

“I never took a bit of stock in what Tom said like that until I come to be in this trouble. I felt right and good, looking out for Miz’ Celestine’s interest and standing true and strong, till they took me off to jail and I writ Miz’ Celestine a letter to please come see ‘bout me and help me out, and give it to the folks there at the jail to mail off for me.

“A sob wrestled inside Laura Lee and she struck silence for a full minute before she could go on.

“Maybe it reached her, and then maybe again it didn’t. Anyhow, I ain’t had a single scratch from Miz’ Celestine, and here I is. But I love her so hard, and I reckon I can’t help myself. Look, gentlemen, Celestine was give to me when I was going on five — ”

The prosecutor shot up like a striking trout and waved his long arm. “If the court please, this is not a street corner. This is a court of law. The witness cannot be allowed to ramble — ”

The judge started as if he had been shaken out of a dream. He looked at the prosecutor and shook his head. “The object of a trial, I need not remind you, is to get at the whole truth of a case. The defendant is unlearned, as she has said. She has no counsel to guide her along the lines of procedure. It is important to find out why an act was committed, as you well know. Please humor the court by allowing the witness to tell her story in her own way.” The judge looked at Laura Lee and told her to go ahead. A murmur of approval followed this from all over the room.

“I don’t mean that her mama and papa throwed her away. You know how it used to be the style when a baby was born to place it under the special care of a older brother or sister, or somebody that had worked on the place for a long time and was apt to stay. That’s what I mean by Celestine was give to me.

“Just going on five, I wasn’t yet old enough to have no baby give to me, but that I didn’t understand. All I did know that some way I loved babies. I had me a old rag doll-baby that my mama had made for me, and I loved it better’n anything I can mention.

“Never will forget the morning mama said she was going to take me upstairs to Miz’ Beaufort’s bedroom to lemme see the new baby. Mama was borned on the Beaufort place just like I was. She was the cook, and everything around the place was sort of under her care. Papa was the houseman and drove for the family when they went out anywhere.

“Well, I seen that tee-ninchy baby laying there in a pink crib all trimmed with a lot of ribbons. Gentlemens, it was the prettiest thing I had ever laid my eyes on. I thought that it was a big-size doll-baby laying there, and right away I wanted it. I carried on so till afterwhile Miz’ Beaufort said that I could have it for mine if I wanted it. I was so took with it that I went plumb crazy with joy. I ask-ed her again, and she still said that she was giving it to me. My mama said so too. So, for fear they might change they minds, I said right off that I better take my baby home with me so that I could feed it my ownself and make it something to put on and do for it in general.

“I cried and carried on something terrible when they wouldn’t leave me take it on out to the little house where we lived on the place. They pacified me by telling me I better leave it with Miz’ Beaufort until it was weaned.

“That couldn’t keep me from being around Celestine every chance I got. Later on I found out how they all took my carrying-on for jokes. Made out they was serious to my face, but laughing fit to kill behind my back. They wouldn’t of done it if they had knowed how I felt inside. I lived just to see and touch Celestine — my baby, I thought. And she took to me right away.

“When Celestine was two, going on three, I found out that they had been funning with me, and that Celestine was not my child at all. I was too little to have a baby, and then again, how could a colored child be the mother of a white child? Celestine belonged to her papa and mama. It was all right for me to play with her all I wanted to, but forget the notion that she was mine.

“Jury-gentlemen, it was mighty hard, but as I growed on and understood more things I knowed what they was talking about. But Celestine wouldn’t allow me to quit loving her. She ever leaned on me, and cried after me, and run to me first for every little thing.

“When I was going on sixteen, papa died and Tom Kimble, a young man, got the job that papa used to have. Right off he put in to court me, even though he was twelve years older than me. But lots of fellows around Savannah was pulling after me too. One wanted to marry me that I liked extra fine, but he was settling in Birmingham, and mama was aginst me marrying and settling way off somewhere. She ruthered for me to marry Tom. When Celestine begin to hang on me and beg and beg me not to leave her, I give in and said that I would have Tom, but for the sake of my feelings, I put the marriage off for a whole year. That was my first good chance to break off from Celestine, but I couldn’t.

“General Beaufort, the old gentleman, was so proud for me to stay and pacify Celestine, that he built us a nice house on the place and made it over to us for life. Miz’ Beaufort give me the finest wedding that any colored folks had ever seen around Savannah. We stood on the floor in the Beaufort parlor with all the trimmings.

“Celestine, the baby, was a young lady by then, and real pretty with reddish-gold hair and blue eyes. The young bloods was hanging after her in swarms. It was me that propped her up when she wanted to marry young J. Stuart Clairborne, a lawyer just out of school, with a heap of good looks, a smiling disposition, a fine family name and no money to mention. He did have some noble old family furniture and silver. So Celestine had her heart’s desire, but little money. They was so happy together that it was like a play.

“Then things begin to change. Mama and Miz’ Beaufort passed on in a year of each other. The old gentleman lingered around kind of lonesome, then one night he passed away in his sleep, leaving all he had to Celestine and her husband. Things went on fine for five years like that. He was building up a fine practice and things went lovely.

“Then, it seemed all of a sudden, he took to coughing, and soon he was too tired all the time to go to his office and do around like he used to. Celestine spent her money like water, sending her husband and taking him to different places from one end of the nation to the other, and keeping him under every kind of a doctor’s care.

“Four years of trying and doing like that, and then even Celestine had to acknowledge that it never did a bit of good. Come a night when Clairborne laid his dark curly head in her lap like a trusting child and breathed his last.

“Inside our own house of nights, Tom would rear and pitch like a mule in a tin stable, trying to get me to consent to pull out with him and find us better-paying jobs elsewhere. I wouldn’t hear to that kind of a talk at all. We had been there when times was extra good, and I didn’t aim to tear out and leave Miz’ Celestine by herself at low water. This was another time I passed up my chance to cut aloose.

“The third chance wasn’t too long a-coming. A year after her husband died, Miz’ Celestine come to me and told me that the big Beaufort place was too much for her to keep up with the money she had on hand now. She had been seeking around, and she had found a lovely smaller house down at Jacksonville, Florida. No big grounds to keep up and all. She choosed that instead of a smaller place around Savannah because she could not bear to sing small where she had always led off. An’ now she had got hold of a family who was willing to buy the Beaufort estate at a very good price.

“Then she told me that she wanted me to move to Florida with her. She realized that she had no right to ask me no such a thing, but she just could not bear to go off down there with none of her family with her. Would I please consent to go? If I would not go with her, she would give Tom and me the worth of our property in cash money and we could do as we pleased. She had no call to ask us to go with her at all, excepting for old-time love and affection.

“Right then, jury-gentlemens, I knowed that I was going. But Tom had ever been a good husband to me, and I wanted him to feel that he was considered, so I told her that I must consult my pillow. Give her my word one way or another the next day.

“Tom pitched a acre of fits the moment that it was mentioned in his hearing. Hollered that we ought to grab the cash and, with what we had put away, buy us a nice home of our own. What was wrong with me nohow? Did I aim to be a wishbone all my days? Didn’t I see that he was getting old? He craved to end his days among his old friends, his lodges and his churches. We had a fine cemetery lot, and there was where he aimed to rest.

“Miz’ Celestine cried when he told her. Then she put in to meet all of Tom’s complaints. Sure, we was all getting on in years, but that was the very reason why we ought not to part now. Cling together and share and lean and depend on one another. Then when Tom still helt out, she made a oath. If Tom died before she did, she would fetch him back and put him away right at her own expense. And if she died before either of us, we was to do the same for her. Anything she left was willed to me to do with as I saw fit.

“So we put in to pack up all the finest pieces, enough and plenty to furnish up our new home in Florida, and moved on down here to live. We passed three peaceful years like that, then Tom died.”

Laura Lee paused, shifted so that she faced the jury more directly, then summed up.

“Maybe I is guilty sure enough. I could be wrong for staying all them years and making Miz’ Celestine’s cares my own. You gentlemens is got more book-learning than me, so you would know more than I do. So far as this fracas is concerned, yeah, I hurted this plaintive, but with him acting the way he was, it just couldn’t be helped. And ‘tain’t nary one of you gentlemens but what wouldn’t of done the same.”

There was a minute of dead silence. Then the judge sent the prosecutor a cut-eye look and asked, “ Care to cross-examine?”

“That’s all!” the prosecutor mumbled, and waved Laura Lee to her seat.

“I have here,” the judge began with great deliberation, “the note made by Mrs. J. Stuart Clairborne with the plaintiff. It specifies that the purpose of the loan was to finance the burial of Thomas Kimble.” The judge paused and looked directly at Laura Lee to call her attention to this point. “The importance to this trial, however, is the due date, which is still more than three months away.”

The court officers silenced the gasps and mumbles that followed this announcement.

“It is therefore obvious why the plaintiff has suppressed this valuable piece of evidence. It is equally clear to the court that the plaintiff knew that he had no justification whatsoever for being upon the premises of Mrs. Clairborne.”

His Honor folded the paper and put it aside, and regarded the plaintiff with cold gray eyes.

“This is the most insulting instance in the memory of the court of an attempt to prostitute the very machinery of justice for an individual’s own nefarious ends. The plaintiff first attempts burglary with forceful entry and violence and, when thoroughly beaten for his pains, brazenly calls upon the law to punish the faithful watch-dog who bit him while he was attempting his trespass. Further, it seems apparent that he has taken steps to prevent any word from the defendant reaching Mrs. Clairborne, who certainly would have moved heaven and earth in the defendant’s behalf, and rightfully so.”

The judge laced the fingers of his hands and rested them on the polished wood before him and went on.

The protection of women and children, he said, was inherent, implicit in Anglo-Saxon civilization, and here in these United States it had become a sacred trust. He reviewed the long, slow climb of humanity from the rule of the club and the stone hatchet to the Constitution of the United States. The English-speaking people had given the world its highest concepts of the rights of the individual, and they were not going to be made a mock of, and nullified by this court.

“The defendant did no more than resist the plaintiff’s attempted burglary. Valuable assets of her employer were trusted in her care, and she placed her very life in jeopardy in defending that trust, setting an example which no decent citizen need blush to follow. The jury is directed to find for the defendant.”

Laura Lee made her way diffidently to the judge and thanked him over and over again.

“That will do, Laura Lee. I am the one who should be thanking you.”

Laura Lee could see no reason why, and wandered off, bewildered. She was instantly surrounded by smiling, congratulating strangers, many of whom made her ever so welcome if ever she needed a home. She was rubbed and polished to a high glow.

Back at the house, Laura Lee did not enter at once. Like a pilgrim before a shrine, she stood and bowed her head. “I ain’t fitten to enter. For a time, I allowed myself to doubt my Celestine. But maybe nobody ain’t as pure in heart as they aim to be. The cock crowed on Apostle Peter. Old Maker, please take my guilt away and cast it into the sea of forgetfulness where it won’t never rise to accuse me in this world, nor condemn me in the next.”

Laura Lee entered and opened all the windows with a ceremonial air. She was hungry, but before she would eat, she made a ritual of atonement by serving. She took a finely wrought silver platter from the massive old sideboard and gleamed it to perfection. So the platter, so she wanted her love to shine.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you all the book excerpts in The Saturday Evening Post dated May-June, 202