Art that was created for newspapers and magazines was designed to be seen once or twice and thrown away. But today these pictures have been rediscovered by experts and are enjoying a whole new respectability. Art that was once used to sell life insurance or dishwashing detergent is ending up in art museums long after the products they originally promoted have disappeared.

Such pictures were once dismissed as “too commercial” by the fine art community. As some fine art movements became more self-absorbed and esoteric, they also became less comprehensible or relevant to most people’s lives. The art world began taking a second look at the popular arts, such as magazine illustration, commercial art, and cartooning.

A commercial element in a picture actually helped to keep art tethered to reality. Commercial illustrators could not afford the luxury of self-indulgence. They had to relate to their audience. This meant they were more likely to develop technical skills, employ recognizable images, and value traditional beauty. These qualities may have made them unfashionable in today’s fine art world, but it made their art more meaningful and attractive to the public.

The new critical respect for illustration was undoubtedly helped by the fact that commercial art was beginning to bring high prices at fine art auctions. When a Norman Rockwell cover from The Saturday Evening Post sold at Sotheby’s for $46 million in 2013, fine art critics rubbed their eyes and began to recognize the artistic merit in commercial illustration.

The latest splendid example of this “second look” at commercial illustration is now appearing in a major exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, where, in its first one-man show in the U.S., the work of English illustrator W. Heath Robinson is on display. The show includes nearly 70 works on loan from the Heath Robinson Museum in London.

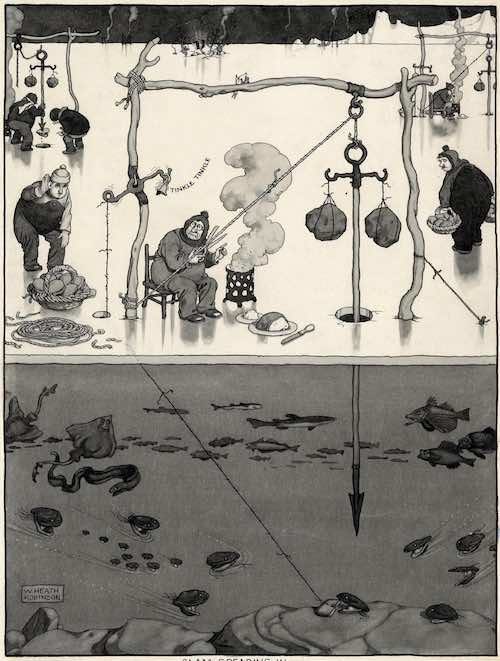

Robinson (1872-1944) was a gifted artist with a whimsical sense of humor. His artwork appeared in magazines in the United States and in England, as well as in a series of children’s books and more classical literature. He created advertising art for nearly 100 different corporate clients, ranging from Shredded Wheat and pickle relish to cars and trains. But he was perhaps most popular for his playful cartoons, which earned him a wide and loyal following. The Heath Robinson Museum reports:

Robinson is best known as the creator of weird mechanical devices and strange gadgets, usually held together with knotted string. … In his early drawings, he set out to satirise the pomposity, fussiness and self-importance of ‘experts’. He soon found that over-complicated machinery would serve as a metaphor for the bureaucracy and arcane processes that such people invent. Much of Heath Robinson’s humorous work centres on the human condition, and the weakness and self-importance of man rather than the gadgets and contraptions themselves.

Just like Rube Goldberg’s crazy inventions in the United States, Robinson’s “gadgets and contraptions” were wildly popular with the public in England. Goldberg and Robinson both struck a chord with readers who were still getting adjusted to “the machine age.” Readers loved cartoons that made fun of automation.

©The William Heath Robinson Trust.

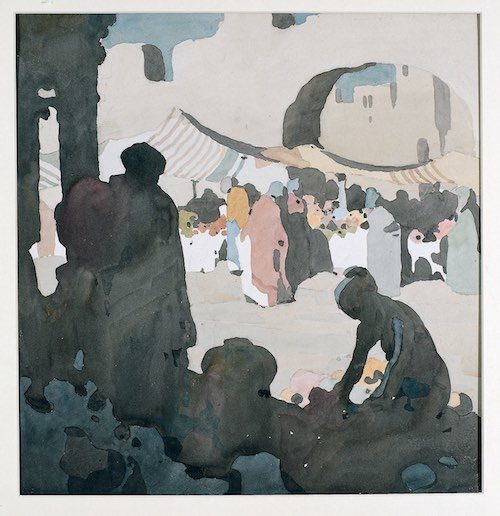

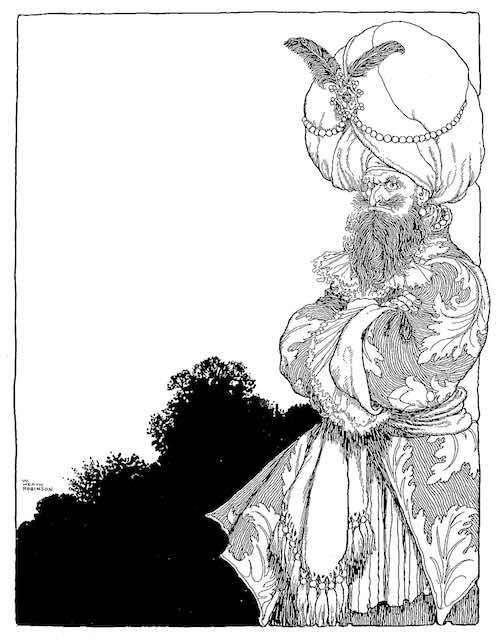

But Robinson’s talents went far beyond cartooning. The assortment of lovely pictures on display in Delaware shows the range of Robinson’s gift, from personal watercolors and landscapes, to book illustrations, to cartoons, to mural designs. Regardless of the category in which he worked, his drawings and paintings all demonstrate Robinson’s trademark sense of design and his rare talent for line and composition. They also make clear that Robinson was a perfectionist who did not compromise his high standards because of a deadline or because his work was to appear in a humble venue.

Robinson worked all his life as a landscape painter and recorded scenes from his travels.

© The William Heath Robinson Trust

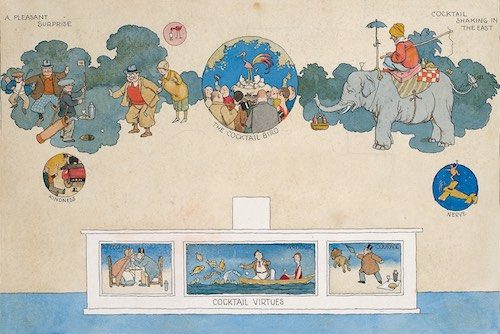

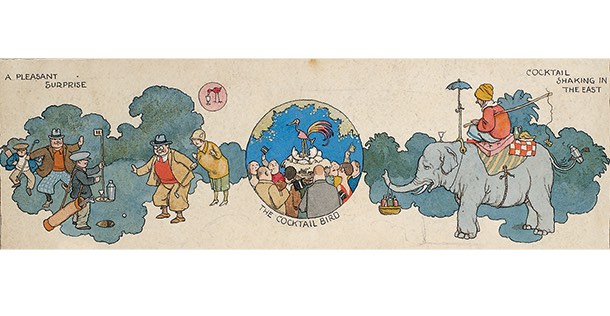

He also embraced unconventional assignments, such as designing a mural for the wall of the bar of the Empress of Britain cruise ship.

© The William Heath Robinson Trust

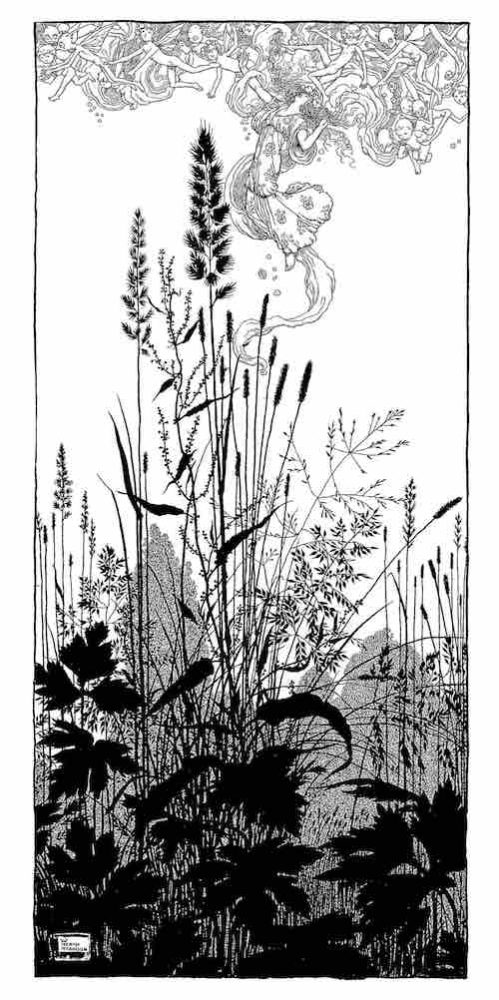

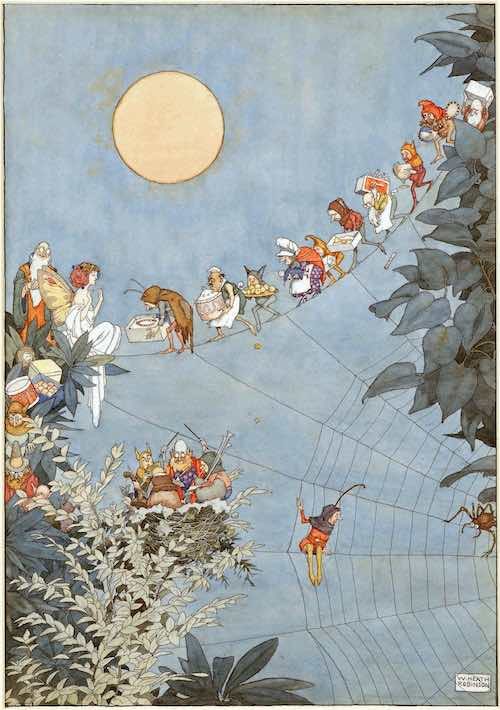

Perhaps his best known strength was his charming pictures that gave life to countless fairy tales for generations of fans.

© The William Heath Robinson Trust

©The William Heath Robinson Trust

©The William Heath Robinson Trust

Most artists would handle a conventional subject, such as this profile of a woman, in a predictable way. But notice now Robinson has given his subject a special flourish with an imaginative design.

©The William Heath Robinson Trust

One rarely finds drawings with such charm and grace in today’s fine art scene. Many artists have largely ceased even to care about these factors. But this highly worthwhile show reminds us of their continuing importance and vitality.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’d like to add to my comment, this is a wonderful lesson, not criticism, to keep in mind when we study material involving art history and art criticism, and even examining our own personal views.

“Such pictures were once dismissed as “too commercial”” & “The new critical respect for illustration was undoubtedly helped by the fact that commercial art was beginning to bring high prices at fine art auctions.”

M. C. Escher’s “Ascending & Descending” and Mr. Gurney’s “Scholar’s Staircase” excellent and enjoyable works come to mind—resulting in a sensation we can walk either way, depending. Yet, as above-mentioned, in practice, professedly also go both ways at the same time.

Thanks for putting the spotlight on this diverse and deserving artist, and kudos to the Saturday Evening Post for working with Mr. Apatoff, one of the leading writers on the art of illustration.