Black History Month pays homage to the many African Americans who have shaped history, from Rosa Parks to Martin Luther King Jr. Yet there are a number of significant African Americans whose achievements are not as widely remembered. If you’ve never heard of Maria P. Williams you’re certainly not alone, but her cinematic achievements paved the way for countless Black women who followed in her footsteps; and her life is just as interesting as her work.

While African American filmmakers have been around since the birth of cinema, their achievements have gone largely unrecognized until recently. Black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company – one of the first Black production companies led by brothers George and Noble Johnson, widely considered the first African American movie star – made what became known as “race films” for segregated audiences, featuring nearly all-Black casts to craft a self-determined image of African American life. Yet, the vast majority of Black cinematic contributions from the early 20th century have been lost, with just four minutes of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s final film, By Right of Birth (1921) remaining.

The remaining four minutes of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s film, By Right of Birth, includes a number of short clips and interior titles, though some appear to be out of order. (Library of Congress)

Black women played a number of important roles in early African American cinema as well, though their contributions have been largely overshadowed by those of their male counterparts. Indeed, women like Alice B. Russell and Eloise Gist rarely receive recognition for their work, despite acting in and producing many of their husbands’ films. Of the several women involved in early Black cinema, Maria P. Williams stands out for her singular achievement as the first African American woman to write, produce, and act in her own film, Flames of Wrath.

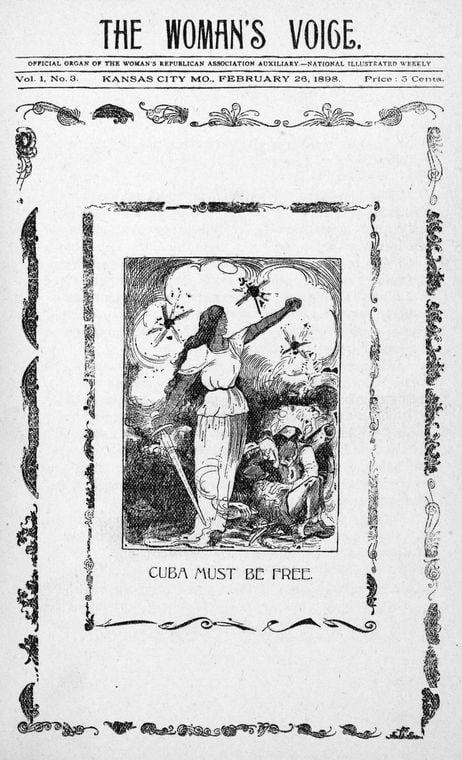

Prior to entering the film industry Maria Williams was a social activist and educator, traveling across Kansas to lecture on topics such as politics and social justice. By 1891, her passion for social change led her to a local Kansas City weekly newspaper titled New Era, where she worked as editor-in-chief for three years before starting her own newspaper, The Women’s Voice, sponsored by the “colored women’s auxiliary of the Republican party.” According to Film School Rejects columnist Emily Kubincanek, Williams’ paper focused on “timely topics” much like her lectures.

Williams continued to be an active political figure well into the 20th century, publishing her memoir My Work and Public Sentiment in 1916 to document her life and social views. The title page of her book identifies Williams as a “national organizer” for the Good Citizens League; 10 percent of all sales were dedicated toward decreasing crime in the African American community.

Williams did not become involved in cinema until her marriage to African American entrepreneur and business owner Jesse L. Williams, among whose many business endeavors was a privately owned movie theater in Kansas City. The couple later went on to form their own production company, Western Film Producing Company and Booking Exchange, where Maria served as secretary and treasurer. It was under this banner that Williams made her 1923 silent film, Flames of Wrath, a five-reel crime drama that cemented her position as a pioneer of Black cinema.

While five-reel films were relatively common by 1920, it was especially rare for such a project to be headed by a woman, and an African American one, at that. Just one reel of film is 1,000 feet long and adds up to about 15 minutes of run-time, making the physical act of cutting and splicing a reel together very demanding. During the early years of cinema, this work was considered unskilled labor and was often completed by uneducated women, yet once sound and music was added into the mix, men deemed the work “too complex” for women to manage.

Despite the monumental achievement of Williams’ work, very little is known about the production of her film. Advertised as a “five reel mystery drama, written, acted and produced entirely by colored people” in the Norfolk Journal and Guide, Flames of Wrath was distributed to African-American theatres across southern America to much success. In a letter to the manager of the Douglass Theatre in Macon, Georgia – the biggest Black theater in the city – Florida cinema manager Roger Wilson boasted that the film had “never lost a dollar to an exhibitor in all of its rounds.”

Williams herself starred in the film as a prosecutor, leading the case against C. Dates for the murder and robbery of P.C. Gordon. When Dates is found guilty, he is sentenced to ten years in jail, yet he soon escapes to retrieve the diamond ring stolen from his victim, which he had buried in a nearby park. Before he arrives, however, the ring is found by a young boy who gives it to his older brother, and after he consults an unscrupulous lawyer, the ring becomes the object of an intricate plot.

While Flames of Wrath was thought to be lost for many decades, the UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library acquired a single frame of the movie in 1992 with George P. Johnson’s collection. An African American producer and part-owner of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company himself, Johnson’s collection houses much of what little remains of Black Americans in silent cinema.

Little record of Williams exists between the release of her silent film and her death in 1932. Historians believe that she stopped producing films following her husband’s death in 1923, and so Flames of Wrath remains the filmmaker’s sole cinematic contribution that we know of.

In an ironic twist of fate, Williams herself was violently murdered nearly ten years after the release of her crime drama. She was reportedly approached by a stranger requesting aid for a sick brother and lured out of the house, only to be found shot by the side of a road several miles away. While the extent of the criminal investigation into Williams’ death is unclear, the murder remains officially unsolved.

Williams’ historic cinematic achievements may be predominantly lost to history, no doubt in large part due to her untimely death, but her achievements have certainly paved the way for Black female directors of today. From her work as a schoolteacher and lecturer to political activist turned filmmaker, Maria Williams led a fascinating life that could very well be the subject of its own movie.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Jennie, thank you for this great feature on Maria Williams, and the roles Black women played on the screen and behind the scenes in the early 20th century’s film industry. I wasn’t familiar with her, or her works previously. I appreciate the time and historical research you did here, including the links, of course.

Ms. Williams was a one-woman powerhouse, and a force to be reckoned with. I was saddened to read she was murdered, and that it’s still an unsolved mystery. I can say this much: whoever did it was jealous and felt threatened by her, even many years after she stopped producing films. Terrible.

I think you might be onto something in your last paragraph about a film on her life. Writing this now, an image of Alfre Woodard flashed into my mind. A favorite actress of mine who happens to be Black. With that said, maybe you could get this article into the hands of some Black female filmmakers and those specializing in documentaries looking for a worthy project. It certainly couldn’t hurt to try, so why not?