One of the worst economic panics in the U.S. was caused by a president’s executive order.

In the 1830s, America enjoyed a robust economy. Cotton prices were high, and there was a booming market in Midwestern land. Between 1834 and 1836, land sales jumped 500 percent.

Speculators were grabbing up land at bargain prices and paying with bank notes from unregulated state banks, which often didn’t have enough coin to back up those notes. Consequently, the value of a note of the same denomination might vary wildly from one bank to another. (As a service to businessmen, the Post regularly reported the fluctuating values of several important bank notes.)

Andrew Jackson worried that too much federal land was being bought with over-valued paper dollars. Remembering how his Tennessee constituents lost their fortunes in the Panic of 1819 because of land speculation and bank failures, he didn’t trust banks and he despised speculators.

As one of his last acts in office, in 1836, Jackson took action with an executive order — the Specie Circular — which required all future land sales to be paid in specie: gold or silver coin.

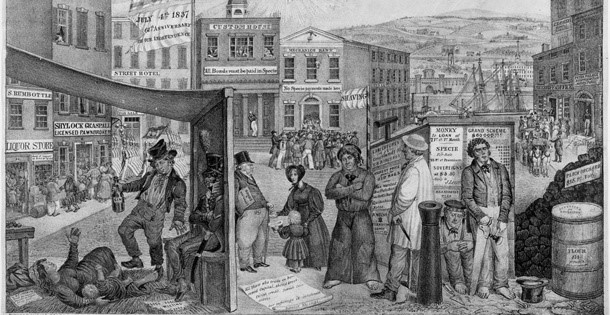

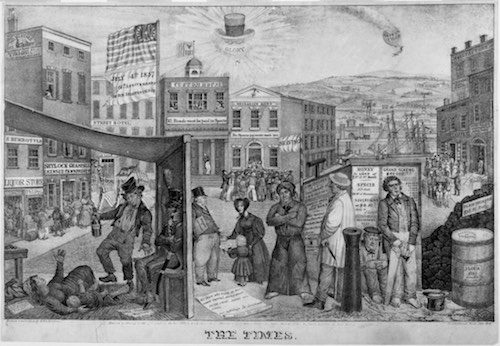

Suddenly, specie was in great demand, and banks couldn’t get enough of it. A specie shortage led to the collapse of the land market. The value of gold rose while the value of paper dollars fell, and bank customers began withdrawing their money in coin to avoid losing their savings, which only worsened the specie shortage.

Acknowledging that they no longer had enough hard assets to cover their bank notes, the banks of New York, on May 10, 1837, stopped paying depositors in specie. The New York decision started a run on banks across the country as hundreds of thousands of Americans tried to withdraw their money from banks. Following the example of New York, 800 banks across the country stopped paying in specie. Some states tried to shore up their economies by issuing bonds to support the banks, but the states defaulted on the bonds and had to declare bankruptcy. The money supply was reduced to a trickle.

Before the year was out, almost half of America’s banks had failed. Unemployment rose sharply — reaching 25 percent in some areas — and profits, prices, and wages fell. The Panic of 1837 had begun.

It took seven years for the U.S. economy to resume its former growth.

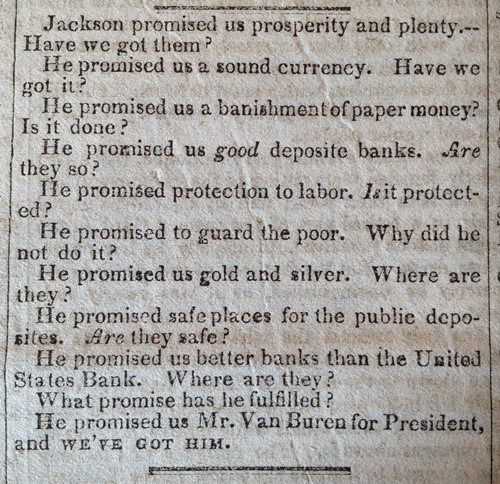

Jackson’s Specie Circular wasn’t his only contribution to the Panic. It was compounded by his decision to shut down the Bank of the United States. In 1836, he fulfilled a campaign promise to withdraw federal funds being held by the bank.

This action was also part of Jackson’s grudge against all banks. He believed the Bank of the United States, in particular, was too powerful and run by elites to benefit themselves. Just before he left office, he withdrew millions in federal funds and deposited them in state banks, many of which were unregulated.

Had the Bank of the United States still been operating in 1837, it might have been a steadying influence in the financial sector. It might have helped in the distribution of specie instead of letting it collect mostly in eastern banks. And it might have reassured the country that a strong, well-regulated, central bank was still conducting business.

Jackson’s moves against banks weren’t the only causes of the Panic of 1837, though. Another large factor was Great Britain’s move to stop British gold flowing into American investments. Not only did this throttle foreign investment, but it forced American banks to raise interest rates.

But Jackson must bear the greater responsibility for letting his fear of banks get the better of him, and of the country.

Fortunately for Jackson, he was able to dodge most of the blame. As often happens, the consequences of one president’s poor judgment become the responsibility of his successor. The New York banks’ specie policy was announced just five weeks into Martin Van Buren’s presidency, and he had to take the heat for Jackson’s policies.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now