From the lighthouses of Maine to the majestic Cascades of Oregon, The Saturday Evening Post has represented every state on its cover. Here are 50 of our favorites.

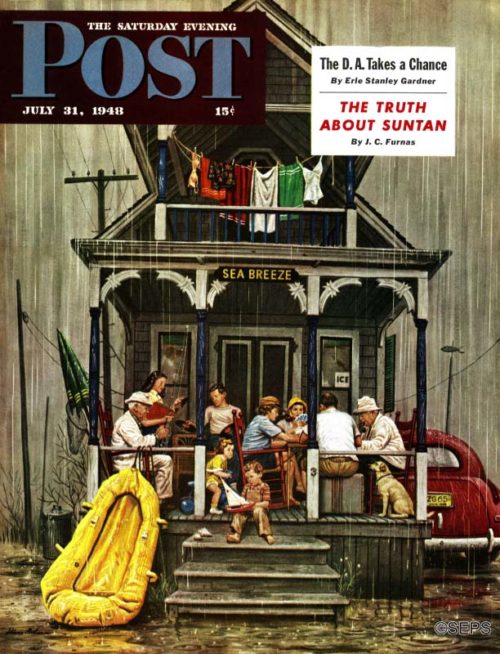

Rainy Day at the Beach

Stevan Dohanos

July 31, 1948

This lonely, wet house surrounded by raindrops and telephone poles would fit right in at Ft. Morgan Beach, Alabama, the narrowest strip of land with nothing but sand, sea grass, and a handful of houses.

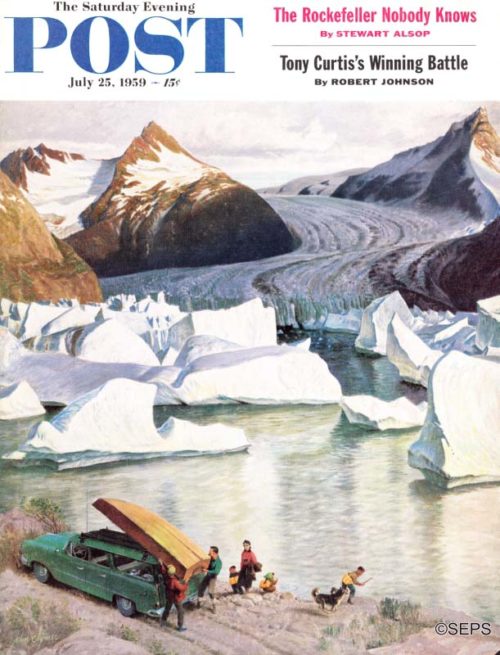

Portage Glacier

John Falter

July 25, 1959

One overheated July day when artist John Clymer was motoring in Alaska he paused at this spot at Portage Glacier. People came and boated around beside the small bergs. Next day, when John returned to sketch, a change of wind had blown Mother Nature’s chopped ice over against the glacier, and the sketching spot was as hot as Tophet. The artist says no, he did not go over and take a ride on the glacier.

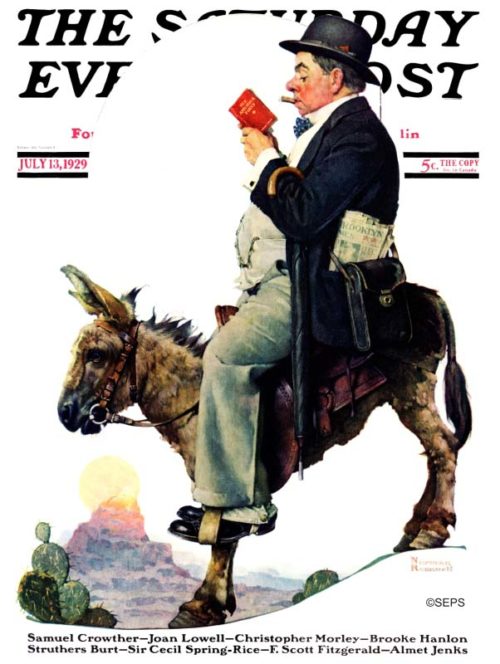

Prospector

Norman Rockwell

July 13, 1929

Rockwell portrayed many forms of transportation in his Saturday Evening Post covers. People traveled by car, train, boat, airplane, soapbox, and stilts, but there was only one way to observe the mountainous terrain of the West successfully – on the back of a mule. When Rockwell traveled through the West, he preferred to tickle his audience with human-sized details, rather than its awesome magnificence.

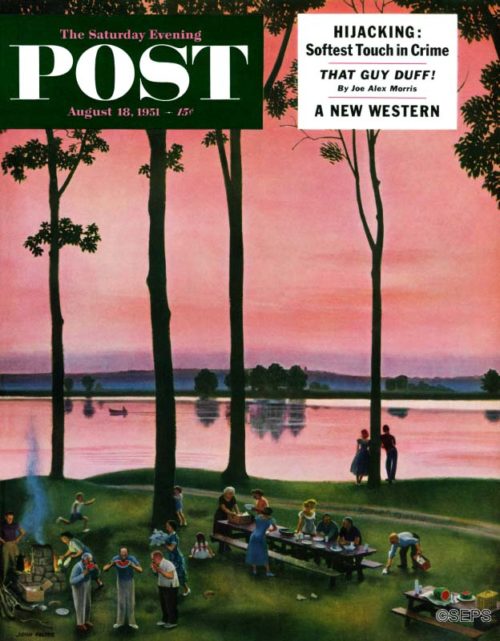

Evening Picnic

John Falter

August 18, 1951

Sometimes Nature rains on a picnic; sometimes she is just neutral; and sometimes, as in this mood caught by John Falter’s brush, she glories in the occasion herself, painting a magic sunset, smoothing the waterways into mirrors, tempering the temperature, even arranging for watermelons to be at their most luscious ripeness.

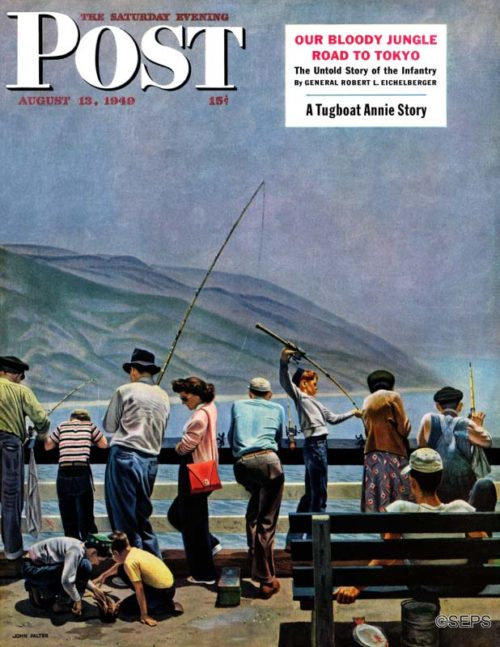

Santa Monica Pier Fishing

John Falter

August 13, 1949

On the long fishing pier at Santa Monica, California, tourists from all over the United States stand packed together like sardines while they try to catch fish. Many of the fishermen go through their routine calmly and expertly; occasionally a greenhorn flies into a tizzy, yelps for the landing net and hauls in a dwarf flounder or something else depressing. Artist John Falter was non-committal about whether he caught anything—besides a Post cover.

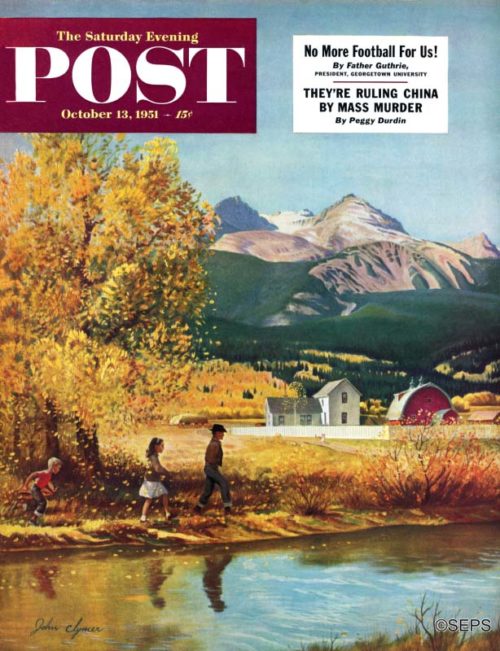

Colorado Creek

John Clymer

October 13, 1951

John Clymer, unable to put all of America on one canvas, settles for a mountain valley in Colorado, where pines and cottonwoods are waging a color battle in the foothills of the Rockies, while up beyond the timber line the slanting sun rays play a red-and-violet game of tag.

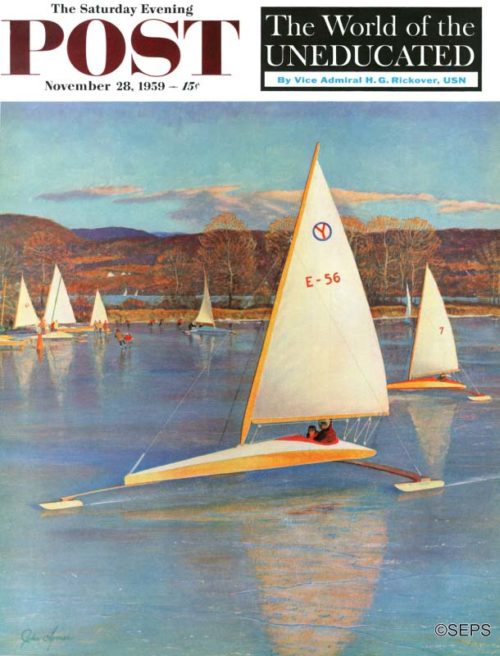

Sailboats

John Clymer

November 28, 1959

Hollanders started putting runners on boats circa 1750. Early United States ice- boaters appeared on the Hudson, where they raced New York Central trains. In 1959, ice-yacht clubs were likely to spring up wherever it didn’t snow too much but where water turned hard in winter. The original caption from 1959 claims this to be Lake Warren, Connecticut, but modern searching could find no such lake. Perhaps it’s Lake Waramaug, near the town of Warren.

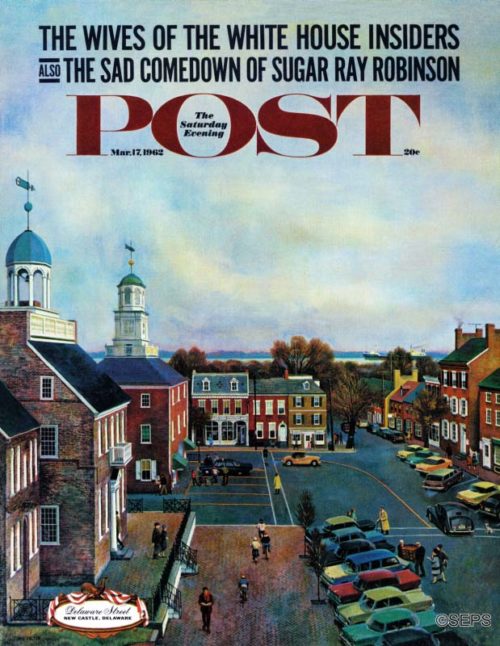

Town Square, New Castle, Delaware

March 17, 1962

New Castle, on the busy Delaware River, is six miles south of the state’s largest city, Wilmington, and two miles off the main highway. Once it was Delaware’s capital. Founded in 1651, it was William Penn’s landing place when he came to America in 1682. Penn is thought to have spent a night in the house at the extreme right of our cover. The spire atop the Court House (left foreground) was used as the center of a twelve-mile radius in part of the 1763-67 survey—to settle a boundary dispute—that resulted in the Mason-Dixon Line, which later played a key part in United States history.

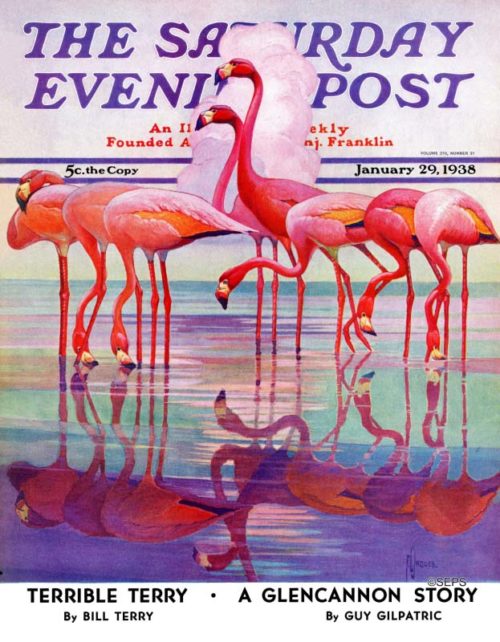

Pink Flamingos

Francis Lee Jacques

January 29, 1938

In the early 1800s, Florida was home to hundreds of thousands of Flamingos. By the turn of the century, the wild birds were all but gone from the state, eradicated by egg and feather collectors. In recent years, the birds seem to be making a slow comeback in the Everglades, a vast improvement over the plastic, front-lawn variety.

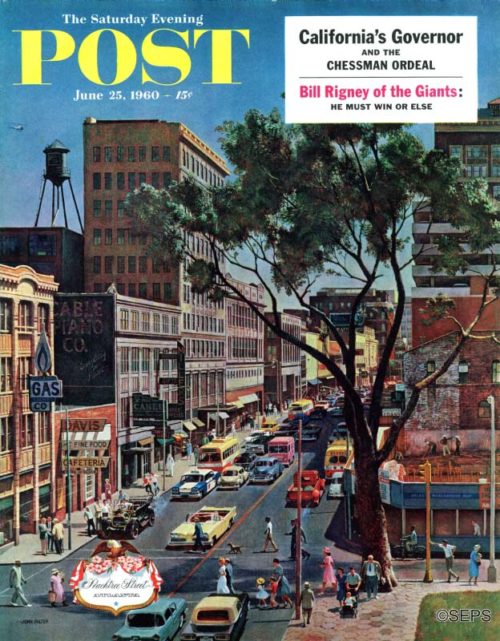

Peachtree Street, Atlanta

John Falter

June 25, 1960

John Falter depicted Peachtree Street at the Harris Street intersection, looking south toward Five Points. The gentleman on crutches at lower left is Ernest Rogers, who was an Atlanta Journal columnist and the popular “Mayor of Peachtree Street.”

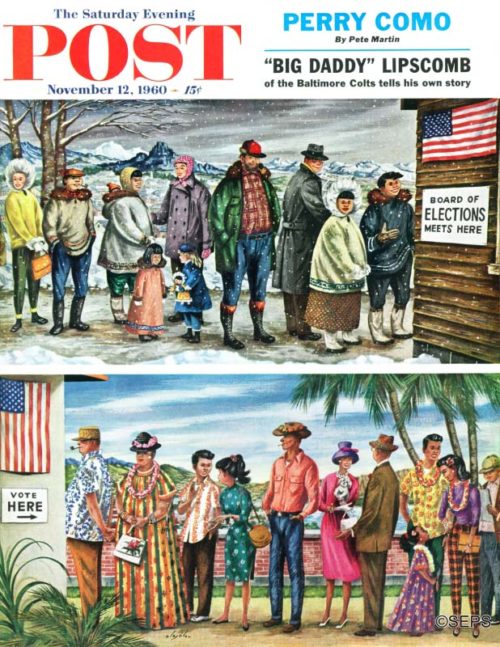

First Vote in the New States

Constantin Alajalov

November 12, 1960

We couldn’t find a cover dedicated solely to Hawaii; here it must share billing with Alaska, the other “new” state in 1960. Cover artist Constantin Alajalov shows the citizens of each state waiting in line to vote in the 1960 presidential election (Nixon v. Kennedy—Kennedy won). Alajalov earned his voting rights the hard way. He was born in Rostov, Russia, and arrived in New York in 1923. Naturalized citizen Alajalov has produced a lighthearted scene, but his underlying message gives us pause: This amalgam of people living together in harmony is bright evidence of the democratic way of life they’re voting to preserve.

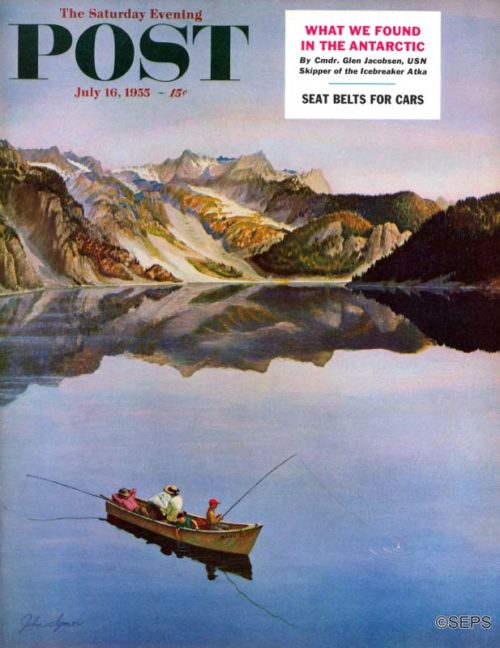

Fishing on a Mountain Lake

John Clymer

July 16, 1955

In America’s Western skylands are many jewel lakes, set in the gold and silver of clasping peaks. This looks to be in the vicinity of Sawtooth National Forest, but which mountain lake is anybody’s guess.

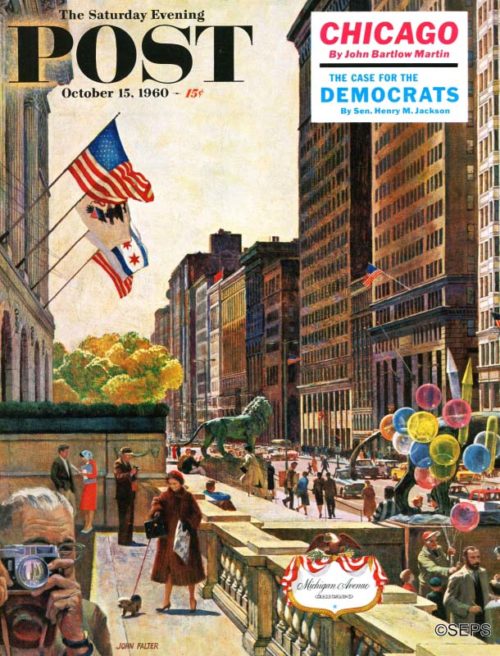

Michigan Avenue, Chicago

John Falter

October 15, 1960

The standard picture-post-card view of Chicago is of Michigan Avenue, looking north toward the Tribune Tower and Wrigley Building. Artist John Falter gives us instead a southern exposure of this elegant avenue—with the Wrigley Building and environs reflected in the camera lens at left. Behind the lofty buildings on the right is the Loop; facing them are the Art Institute, set in Grant Park, and Lake Michigan. The whiskered gent with sketch pad is the late Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright’s mentor and an architect who helped reshape the face of this frisky city. (Sullivan had an office in Orchestra Hall, the second building from right.) We thought we had spotted another eminent Chicagoan, Al Capone, in the foreground. But Falter assures us we’re imagining things.

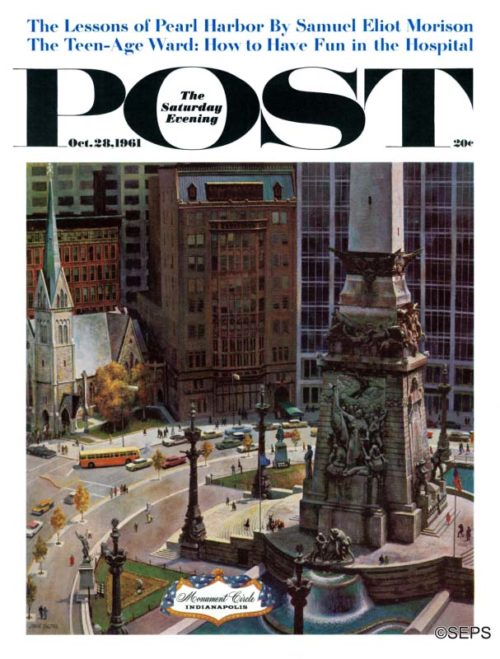

Monument Circle

John Falter

October 28, 1961

Monument Circle takes its name from the limestone memorial to soldiers and sailors at its center. And the circle is at the very center of Indianapolis, which is right in the middle of the Hoosier state. Artist John Falter discerned a faintly French flavor in this scene — perhaps because Indianapolis was planned on the pattern of Washington, D.C., which was laid out by a Frenchman. But consider the English Gothic architecture of Christ Church Cathedral at the left, the vaguely Tudor air of the neighboring Columbia Club, and the bluntly modern design of the Fidelity Building. French, English, or just plain American, the circle suits a city with a half-Greek name.

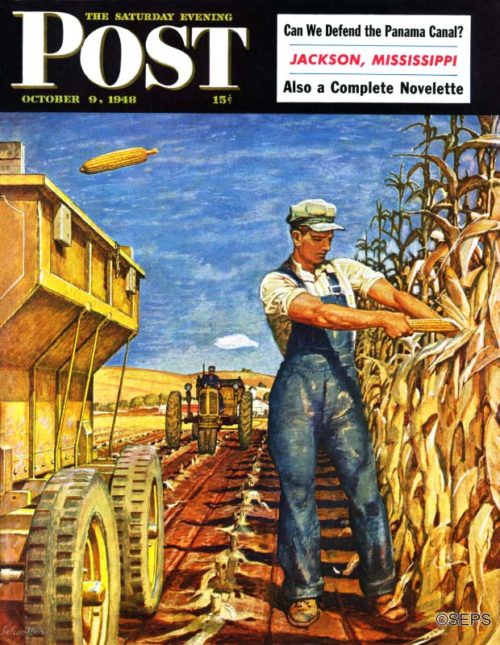

Corn Harvest

Mead Schaeffer

October 9, 1948

This Mead Schaeffer cover shows corn being picked by the “bang-board” method, which allowed a man to throw ears into the wagon without looking, because they would bang against a high board at the far side of the wagon and drop in. By 1948, most big farms used mechanical corn pickers, including the Lawton, Iowa, farm of Louis Peterson, the setting of this picture. The mechanical picker had already been used on much of the field, as the rows of stubble indicate, but the day Schaeffer was there, the machine was busy elsewhere. Farmer Peterson needed a little corn for his hogs. He got it the bang-board way—and Schaeffer got this cover.

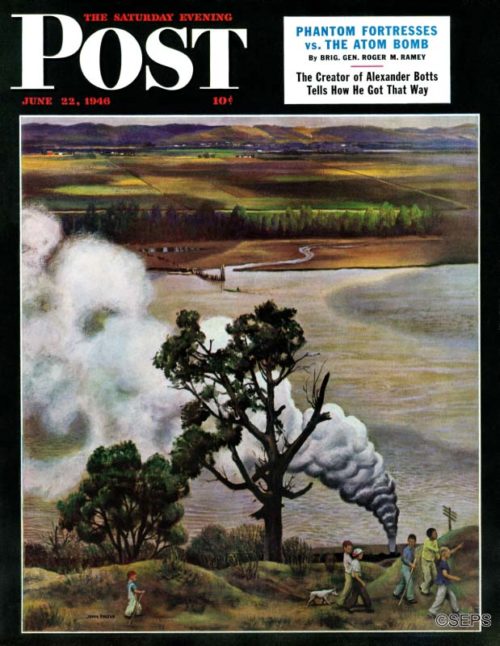

Steam Engine Along the Missouri

John Falter

June 22, 1946

You are looking across one of the great rivers of America—the Missouri. You are in Kansas, gazing across into Missouri. The town in the distance is Armour Junction. Those flat fields across the way are likely to disappear when the Missouri gets one of its expansive moods. John Falter painted the scene when he visited a farm his father had just bought—painted it, in fact, from a bedroom window in the farmhouse. He had paints and brushes, but no canvas, so painted this one over an old picture that came with the house. The tagalong lad bringing up the rear of the little expedition—Lewis and Clark used the same route—is Falter’s nephew.

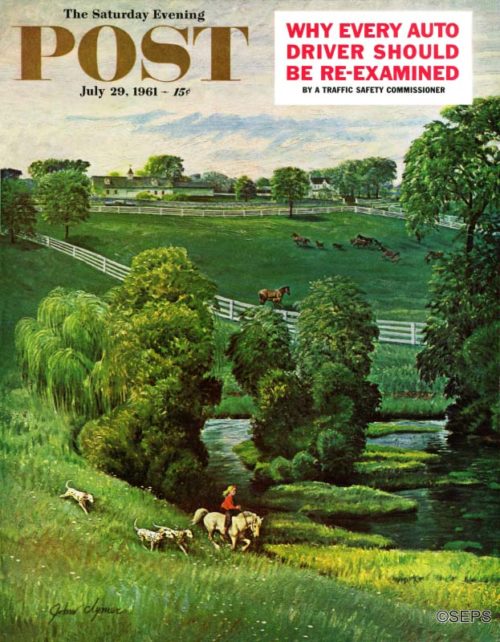

Green Kentucky Pastures

John Clymer

July 29, 1961

Our cover is a composite of scenes observed by artist John Clymer near Lexington. There may be gold—a future Derby winner, that is—among the foals behind the fences of that paddock. But none of the foals seems in a hurry to be over the fence and romping with Goldilocks and her three Dalmatians or thundering down the homestretch at Churchill Downs. Perhaps the reason is that the grass down here doesn’t always seem greener on the other side. This is Bluegrass country.

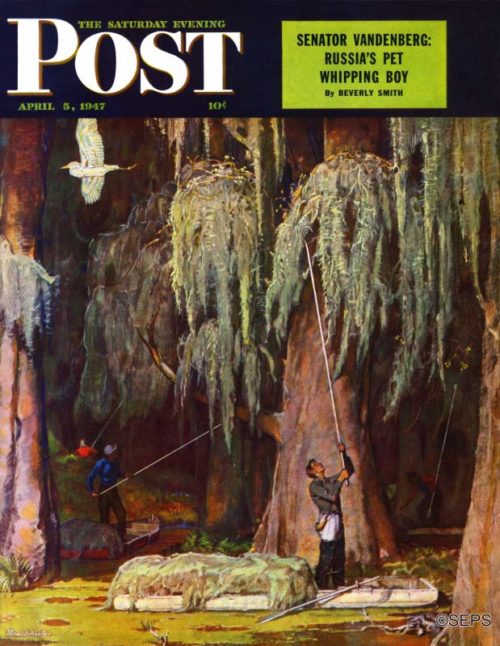

Spanish Moss Pickers

Mead Schaeffer

April 5, 1947

Artist Mead Schaeffer contributes another to our series of regional covers with a scene he sketched south of New Orleans, in the bayou country. Near Lafitte, Louisiana, he watched a harvest distinctive to the South. Moss pickers were hauling down boatloads of the beautiful Spanish moss that festoons trees in the South; the moss was dried and used in upholstering.

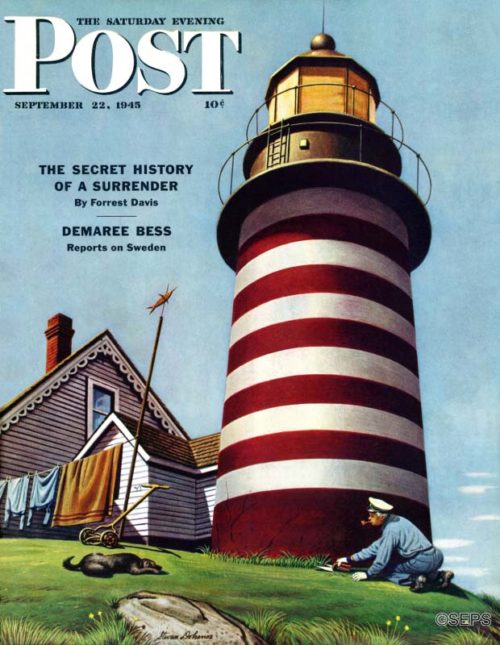

Lighthouse Keeper

Stevan Dohanos

September 22, 1945

The lighthouse on the cover is the West Quoddy Light, Lubec, Maine, but the lighthouse keeper is pruning the grass at Sankaty Light, Nantucket, a neat trick that can happen only in the world of art. What happened was that artist Stevan Dohanos made his preliminary sketches of the West Quoddy Light the summer before. The next year, to freshen his memory on lighthouse detail, he journeyed up to the Sankaty Light. It turned out the Sankaty Light had “a very strong personality of its own,” and wasn’t much good as a source of information on the situation in West Quoddy. However, they were cutting the grass at Sankaty Light, and Dohanos liked that touch of domesticity, so he included it.

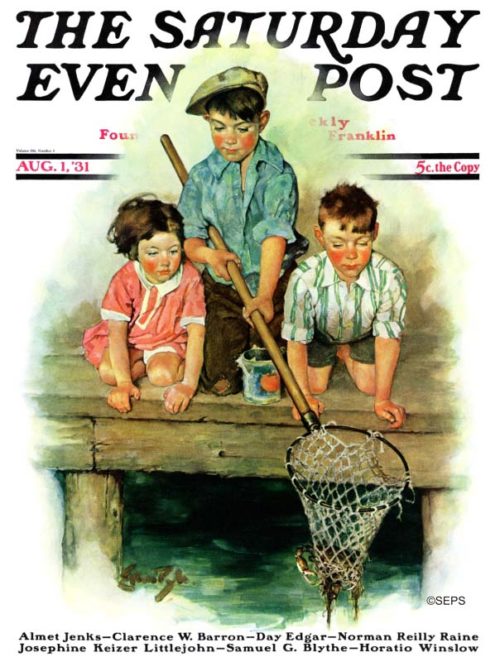

Crabbing

Ellen Pyle

August 1, 1931

The Chesapeake Bay makes a great location for crabbing, with more than 7,000 miles of shoreline and plenty of piers to dip your net. Any good Marylander knows what to do with that fat crab, but these kids don’t look so sure.

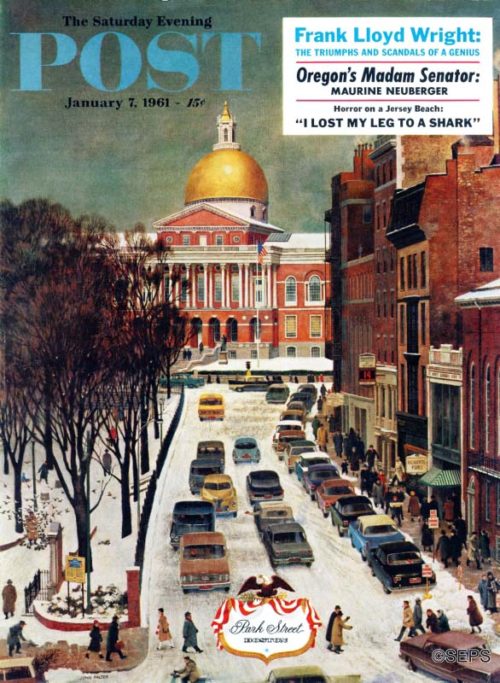

Park Street, Boston

January 7, 1961

Welcome to historic Park Street circa 1961, looking north toward the gold-domed State House. To the left, Boston Common; to the right, the Old Granary Burial Ground, where lie Paul Revere, John Hancock and Samuel Adams. That’s Park Street Church in the foreground; its site is known as “Brimstone Corner.” The yule tree being carted off at lower left indicates that Christmas no longer is banned in Boston, as it was when the Puritans held sway. As for the 1913 Pierce Arrow approaching from the right, artist John Falter tells us it originally belonged to Boston astronomer Percival Lowell, brother of poet Amy Lowell.

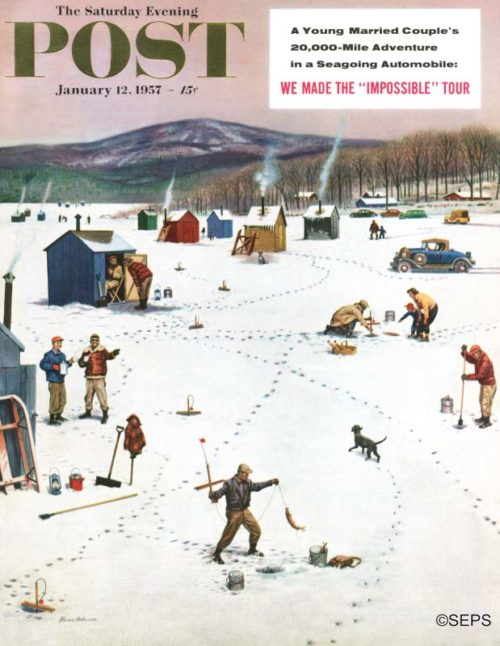

Ice Fishing Camp

Stevan Dohanos

January 12, 1957

These shacks, which sit over fishing holes on the ice, are as cozy as living rooms, though less roomy, and they smell deliciously of coffee with occasional whiffs of kerosene.

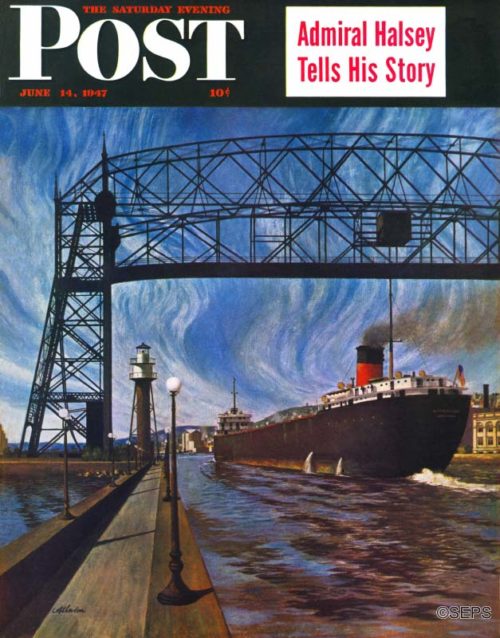

Ore Barge

John Atherton

June 14, 1947

John Atherton’s cover painting is a view of the husky city of Duluth. This is the ship canal through which ore boats moved out to begin their travels in the Great Lakes. The ore came from the great Mesabi Range. Atherton chose a moment when the bridge had lifted to let one of the ore boats pass below.

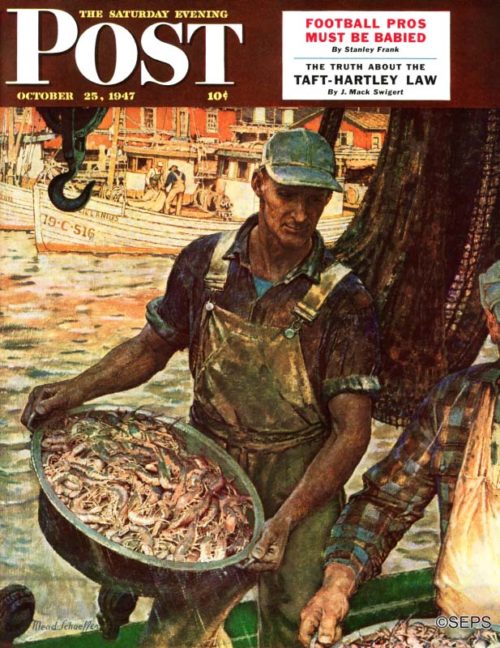

Shrimpers

Mead Schaeffer

October 25, 1947

Mead Schaeffer turned south to Biloxi and its shrimp-fishing fleet. As one who sees shrimp most often in a cocktail, served pretty sparingly, the artist was slightly staggered by the size of the fleet and the volume in which they bring shrimp to the packing houses.

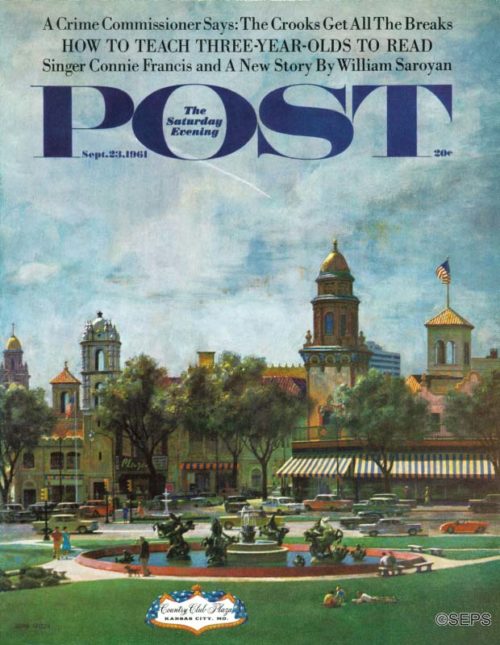

Kansas City

John Falter

September 23, 1961

Spanish architecture in Missouri? If such a state of affairs seems peculiar, consider that the unpredictable Show Me state even has a town named Peculiar (pop. 458), some twenty miles south of here, on U.S. 71. Our cover scene is in Kansas City, “the gateway to the Southwest,” and you are looking at the intersection where U.S. 50, gateway to the Country Club Plaza shopping center, crosses J. C. Nichols Parkway. This elegant community of shops was conceived and built by Jesse Clyde Nichols (1880-1950), to whom the fountain in the foreground is a memorial. The scene appealed to artist John Falter because the Old World architecture seemed to symbolize our nation’s roots — which is not to deny the notion expressed by lyricist Oscar Hammerstein in Oklahoma! that “everything’s up-to-date in Kansas City.”

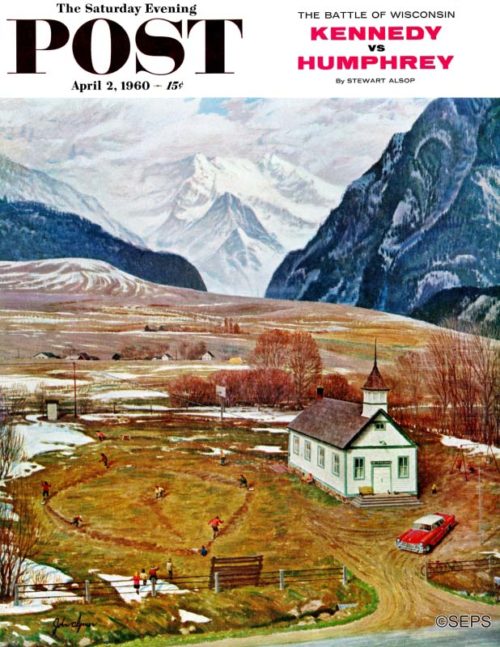

Recess at Pine Creek

John Clymer

April 2, 1960

It’s recess time in Pine Creek, Montana. Artist John Clymer had often passed this one-room schoolhouse en route to nearby Yellowstone National Park, thinking each time that it belonged on the cover of the Post. Clymer confesses that in order to get the part of the Absaroka Mountains on the canvas, he had to turn the schoolyard around.

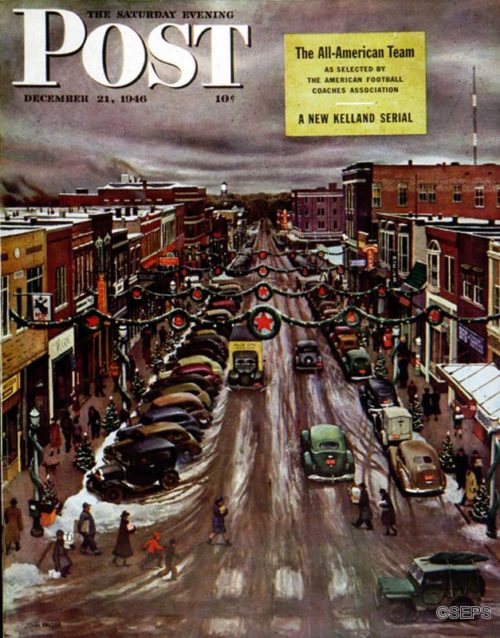

Falls City, Nebraska

John Falter

December 21, 1946

As a setting for his picture of the last-minute Christmas rush, John Falter chose the town where he spent his boyhood: Falls City, Nebraska. The finished job is a mixture of paint and recollection. That water tower in the distance, for example, was a favored roost for Falls City boys on hot summer nights. They liked to sleep there. City authorities met in some alarm — the surrounding platform is seventy-five feet above ground — and forbade it. Falter had no trouble recalling the Christmas rush. As a boy, he worked in his father’s clothing store on this street. A good many customers bought new outfits for the holidays, and young Falter was the pants runner — he ran trousers from the store to the tailor’s, to get them shortened. Only customers appear in this painting. But the artist’s sympathies doubtless are with those on the selling side of the counter.

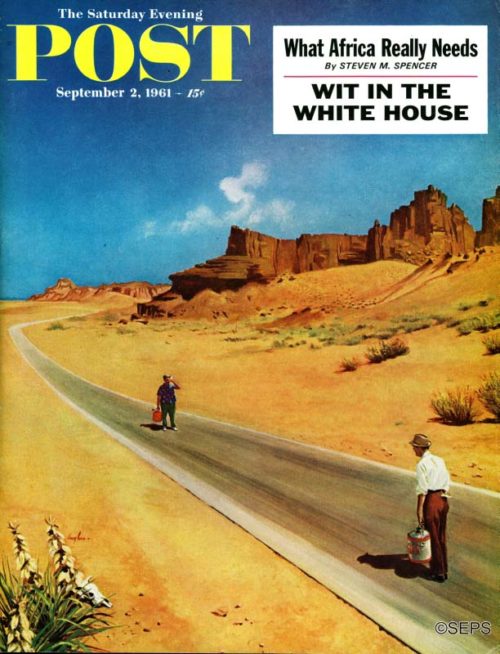

Out of Gas

George Hughes

September 2, 1961

The setting of this depressing encounter is not fifty miles from nowhere. This is nowhere. Artist George Hughes pieced together the landscape from some of the more desolate terrain of the Southwest, where the skies are not cloudy all day and where seldom is heard a discouraging word. Both pedestrians on our cover have, however, been subjected to some rather discouraging words: Exactly 2.6 miles in either direction is a fuelless automobile, and in each automobile sits a wife who was ignored earlier in the day when she suggested, “Don’t you think we’d better stop? The sign at that station says, Last Gas for 40 Miles.” And you should have heard the discouraging mutterings when these chastised males discovered that their spare-gas cans were drier than a sun-baked skull.

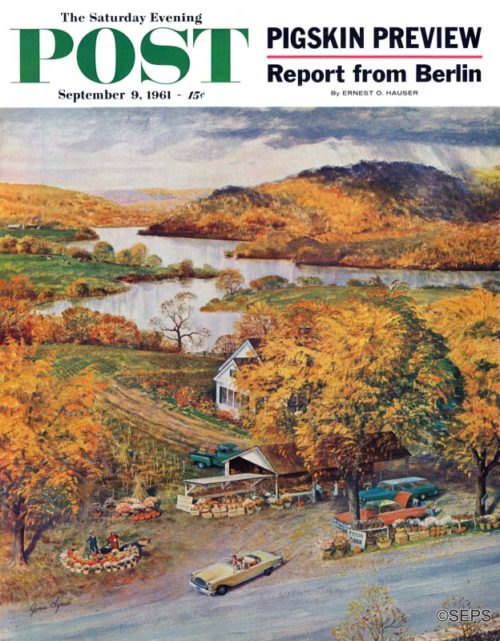

Roadside Vegetable Stand

John Clymer

September 9, 1961

What is more inspiring than the New England countryside in the fall? Indeed, the autumnal delicacies on sale in the foreground of John Clymer’s pumpkin-colored scene inspired us to turn to our bookshelf, where we found Henry David Thoreau saying, “I would rather sit on a pumpkin, and have it all to myself, than to be crowded on a velvet cushion.” (Although there’s no denying that pumpkins are more advantageously used in pies, soups and puddings.)

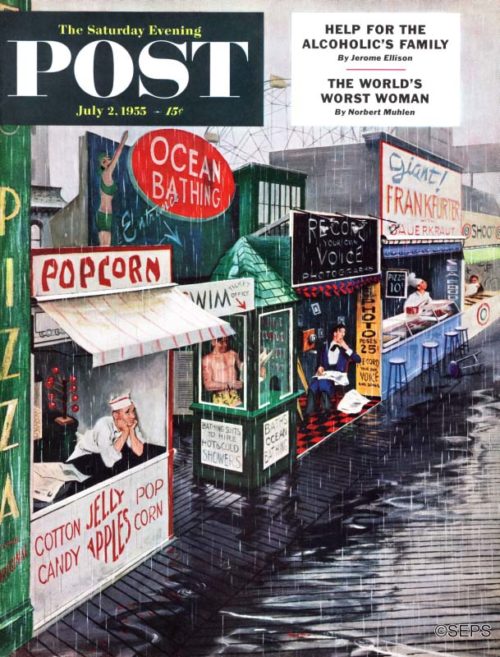

Rain on the Boardwalk

George Hughes

July 2, 1955

True, these poor fellows on Mr. Hughes’ boardwalk are heart-rending, also 5,000 souls sardined into nearby cottages, but as oceans are useless without water, can’t everybody resolve to observe this as Be Kind to Rain Week?

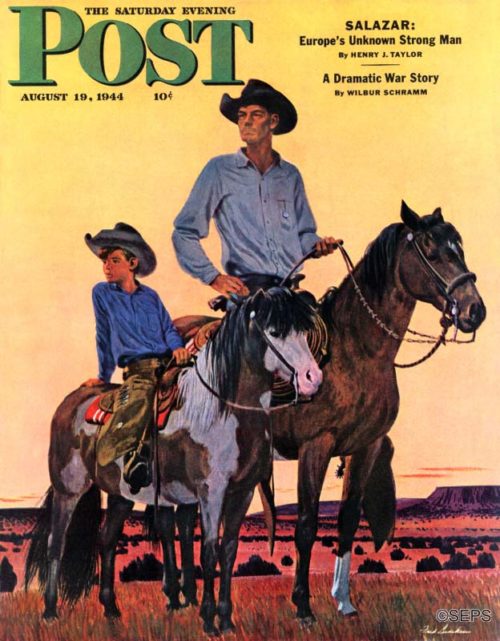

Surveying the Ranch

Fred Ludekens

August 19, 1944

Although Fred Ludekens lived most of his life in California, this scene has a distinctly New Mexican flavor. Ludekens never worked from photos and didn’t use models. Not one to limit himself to just one subject, Ludekens also painted interior images to accompany a Robert Heinlein story about interplanetary travel, which also appeared in the Post.

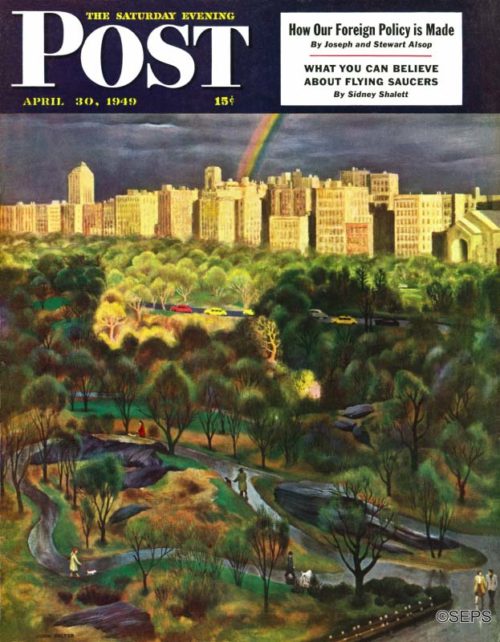

Central Park Rainbow

John Falter

April 30, 1949

When John Falter’s cover painting was accepted, there was lightning trickling down the sky beside the rainbow. Presently the Art Department began to worry—do lightning and rainbows ever show up at the same time? The ever helpful Weather Bureau was asked to look at the Post‘s storm—which has just doused midtown New York and is rumbling away beyond Central Park’s man-made ramparts. “Fair and cooler,” was the comment. “But we never saw a streak of lightning in such bright daylight. Of course, where weather is concerned, anything can happen.” So the picture was delightninged, leaving only that sign of clearing weather, a patch of blue sky large enough to make a sailor a pair of breeches.

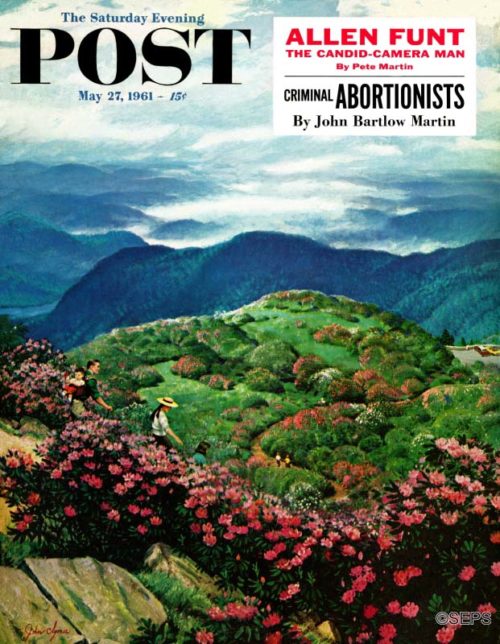

Appalachian Rhododendrons

John Clymer

May 27, 1961

Catawba rhododendron thrives in many sections of the southern Appalachians, but rarely is it so brilliantly beautiful as here at Craggy Gardens, along the Blue Ridge Parkway near Asheville, North Carolina. Our scene shows the trail to Craggy Pinnacle. “Sections of the trail wind through ten-foot-high rhododendrons,” artist John Clymer said. “And the ground is carpeted with the rich-pink petals of the flowers that have fallen.” Clymer’s painting is a preview of a coming attraction: These floriferous slopes look their best in mid-June, as they did in the days when the Catawba and the Cherokee held sway in the Carolinas.

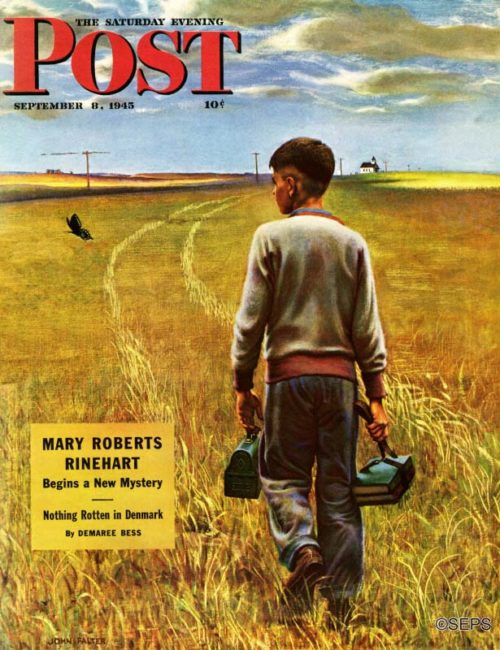

Amber Waves of Grain

John Falter

September 8, 1945

John Falter’s ” back-to-school ” cover shows a lad with a new haircut crossing the fields to a country schoolhouse. This is one that we’re not 100% sure is in North Dakota, but the scene landscape looks decidedly North Dakotan. If you’re from the state, let us know if you disagree.

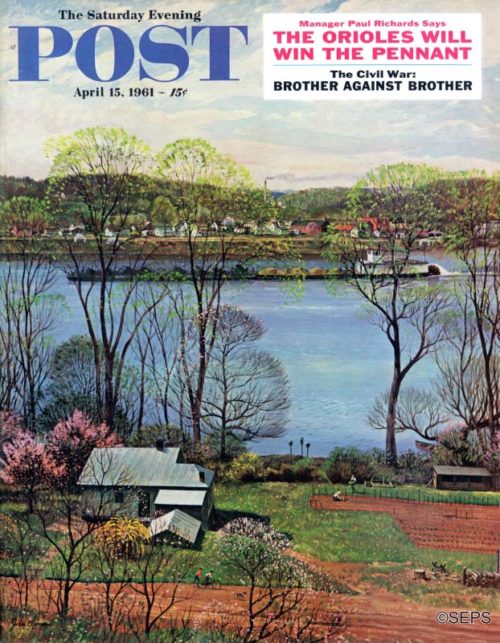

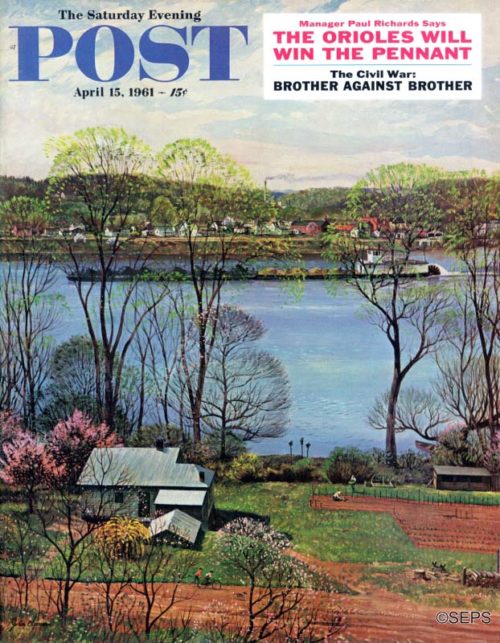

Ohio River in April

John Clymer

April 15, 1961

Heading down the Ohio is a venerable stern-wheeler, push-towing barges loaded with coal and gravel. Cargo by the tens of millions of tons is shipped up and down the Ohio in this manner each year, between Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela, and Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio empties into the Mississippi. (The watershed of the Ohio reaches into fourteen states.) Artist John Clymer formed his riverscape by piecing together the water’s-edge scenes that appealed to him most. The near shore is West Virginia; the far shore is Ohio.

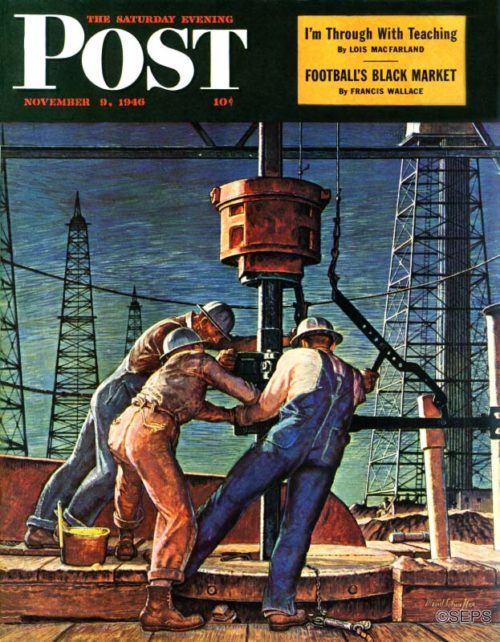

Drilling for Oil

Mead Schaeffer

November 9, 1946

Artist Mead Schaeffer and his wife worked near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, for Schaeffer’s oil country cover—if you can call it ” working.” Had they come to town on a vacation, they couldn’t have had more of a social whirl. Their plane arrived just before sunrise and, much to the Schaeffers’ surprise, the fire chief’s red car was waiting. So was the mayor, who read a proclamation declaring them welcome and offered a key to the city. The Schaeffers found every minute they could spare had been booked for social engagements, and this was true throughout their stay. It was by all odds the warmest reception the Schaeffers have met in their travels working on Post covers, and they went away as impressed with Oklahoma courtesy as with Oklahoma oil.

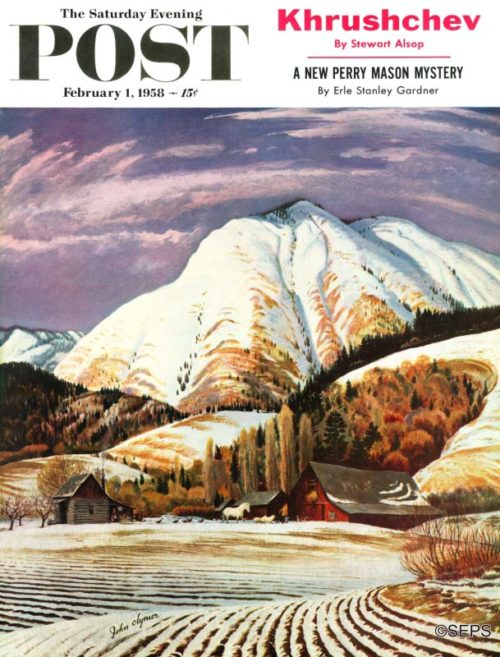

Cascade Mountain Farm

John Clymer

February 1, 1958

At length there’ll come a south-breeze day when the snow on the big hills will give Mr. Frost the heave-ho and begin rollicking down from the skylands in rejoicing cascades. That last word fits in here fine, come to think of it, for John Clymer’s scene is in the Cascade Range.

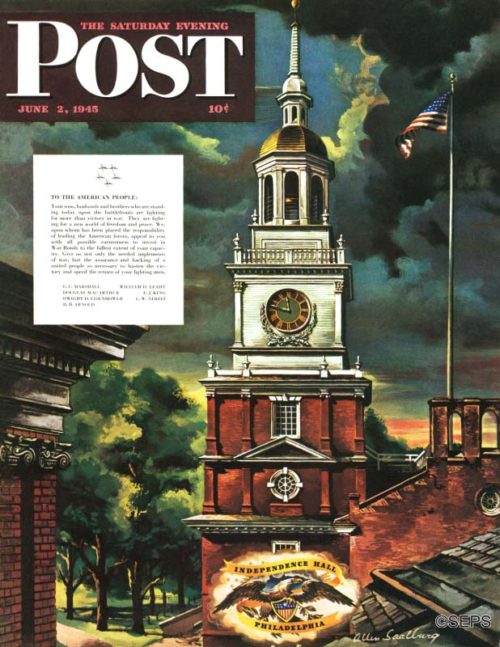

Independence Hall, Philadelphia

Allen Saalburg

June 2, 1945

In 1945, Independence Hall was just across the way from the Post. Allen Saalburg’s painting is a view of Independence Hall looking west. The building at the left was The American Philosophical Society. The Post‘s offices were directly behind the trees in the left foreground.

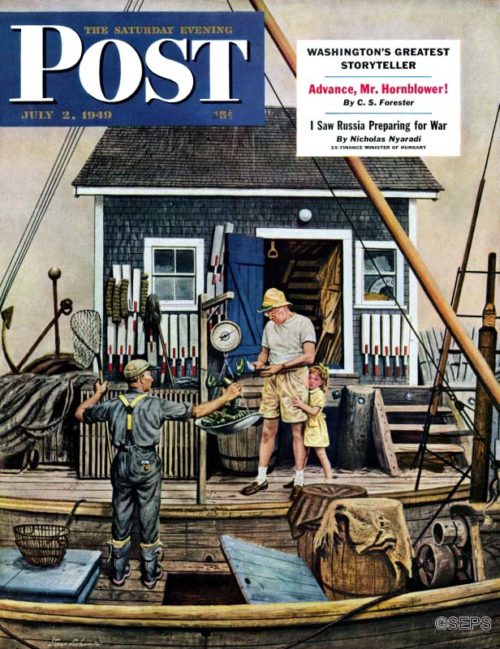

Buying Lobsters

Stevan Dohanos

July 2, 1949

The vacationer in the picture has been caught with that combination of mouth-watering smile and grimace of pain common to human beings when about to pay for a lobster. As for the little girl, you may be too old to recall that the first sight of a lobster is enough to scare the daylights out of anybody. After the first taste, fear vanishes.

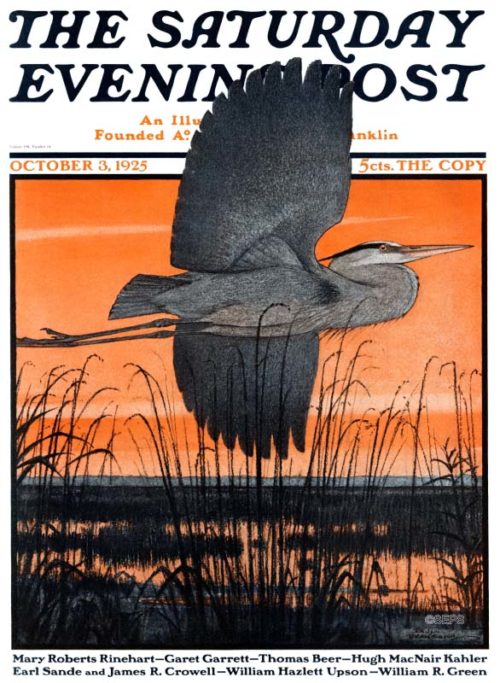

Marsh Bird

Paul Bransom

October 3, 1925

South Carolina has 344,500 acres of salt marsh, the most of any state on the east coast. This regal bird looks as though he’s happy to claim every last one as his own.

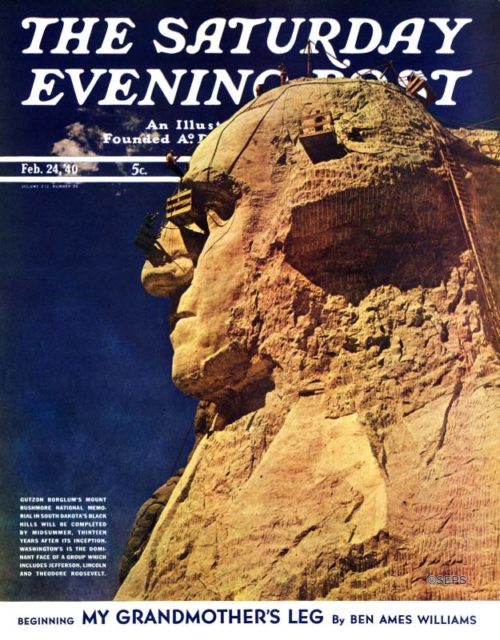

Mt. Rushmore

Lincoln Borglum

February 24, 1940

A photograph instead of an illustration was quite the departure for the Post at the time, but there was important information to document: Mt. Rushmore was scheduled to be completed later that year, so they took the opportunity to capture the monument during its final phase of creation.

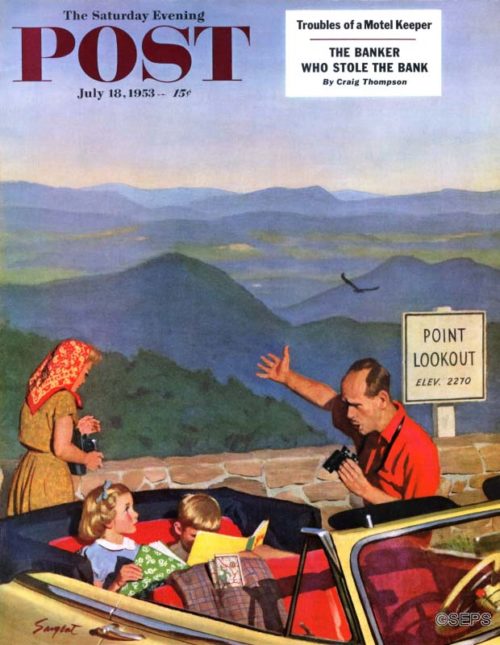

Point Lookout

Richard Sargent

July 18, 1953

Papa has been steering the bus for three days toward Point Lookout, and, having finally made it, is he not justified in decrying the little ones’ disinterest in lookouting? On the other hand, for three days the kids have been peering at interminable scenery; so now that the car has quit jiggling and reading is possible, what is more dutiful than rejoicing in the new hooks that papa bought them to read? Of course, modern readers may long for the days when children were glued to books and not phones.

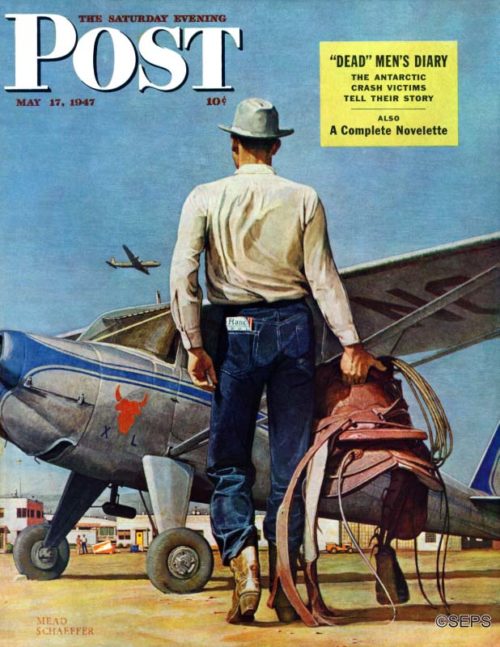

Flying Cowboy/ Airport at Amarillo, TX

Mead Schaeffer

May 17, 1947

“The cowboy carrying his pet saddle to his plane is an everyday sight in the West,” artist Mead Schaeffer wrote when he delivered this painting. “Many a rancher lives in town and commutes to his ranch or ranches by air. The tableland makes landing fields all through the West, and because of the long distances involved, the West takes to planes the way the East takes to cars. Many a business engagement, even luncheon engagements, are kept this way.” One of the flying ranchers, Lee Bivins, was Schaeffer’s model. The background is the airport at Amarillo, Texas.

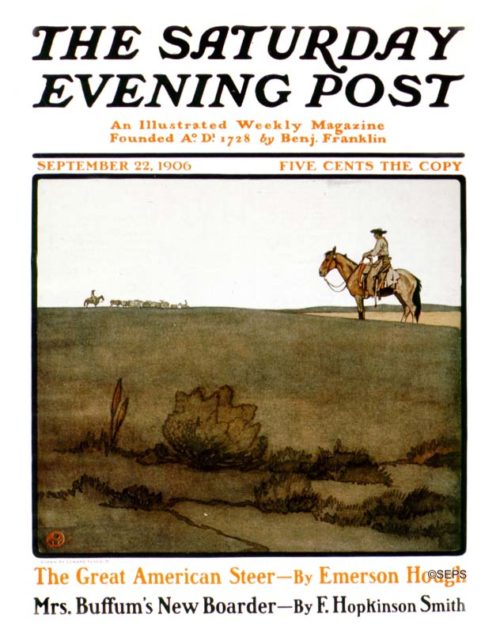

Cowboy

Edward Penfield

September 22, 1906

Artist Edward Penfield is considered the father of the American poster and was an important figure in the field of graphic design. You can see Penfield’s development of the use of simple shapes and limited colors in this work. Are we sure this is Utah? No, but we can’t be too far off the mark.

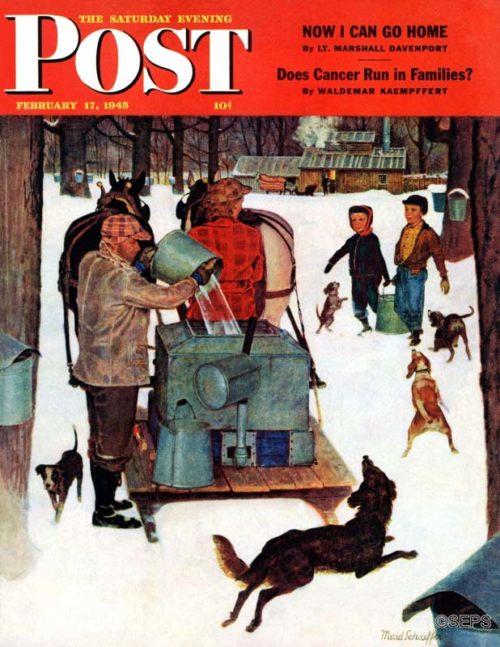

Maple Syrup Time in Vermont

Mead Schaeffer

February 17, 1945

The models are Arlington, Vermont, neighbors of artist Mead Schaeffer’s, Mr. and Mrs. Jim Edgerton and their children. The Edgertons owned one of the best sugar bushes—a bush is a grove of sugar trees—in that section. The shed in the background is the boiling-off house. Vermont farmers can, and do, argue for hours and days over what is the best time to tap. The season starts as early as February and may end as late as April.

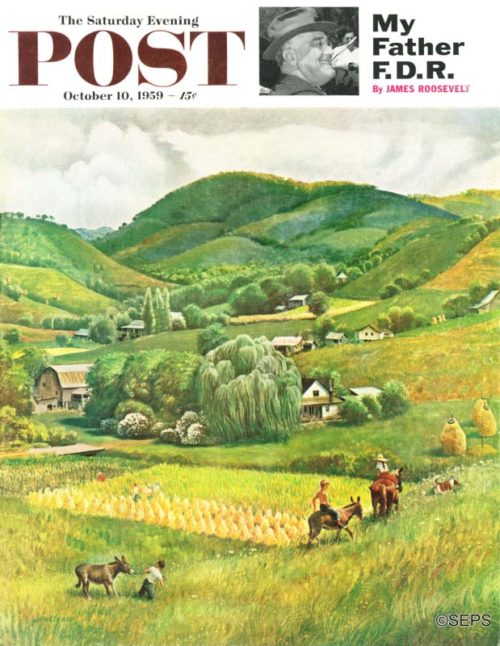

Blue Ridge Burro Ride

John Clymer

October 10, 1959

When those green highlands are seen from afar, they are blue, as highlands are wont to be. Hence, long ago somebody had an inspiration and named them the Blue Ridge Mountains. In the foreground you see a stationary burro, a detail which painter John Clymer probably considers a still life. It’s a pretty fair bet that fifteen minutes from now the animal will still be still.

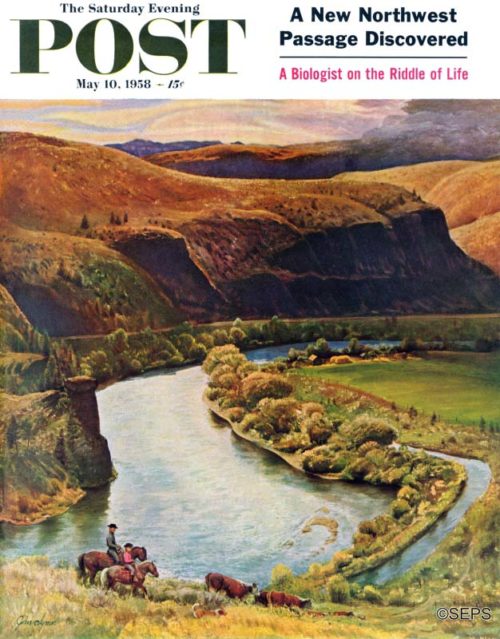

Yakima River Cattle Roundup

John Clymer

May 10, 1958

This is the Yakima River in Washington, not far from artist John Clymer’s boyhood home in Ellensburg; here, one side of the stream (see irrigation canal) is for farming, and the other side for looking. At this river bend Clymer and his father often fished for trout and, furthermore, caught same. In case this lovely spot gives you ideas about temporarily leaving home, just off the bottom of the cover is U.S. Highway No. 10.

Ohio River in April

John Clymer

April 15, 1961

Heading down the Ohio is a venerable stern-wheeler, push-towing barges loaded with coal and gravel. Cargo by the tens of millions of tons is shipped up and down the Ohio in this manner each year, between Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela, and Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio empties into the Mississippi. (The watershed of the Ohio reaches into fourteen states.) Artist John Clymer formed his riverscape by piecing together the water’s-edge scenes that appealed to him most. The near shore is West Virginia; the far shore is Ohio.

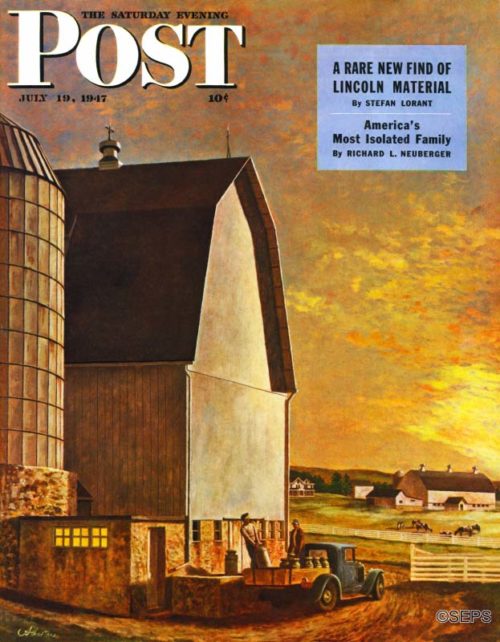

Dairy Farm

John Atherton

July 19, 1947

Artist John Atherton paints an early morning scene in the rich dairy country of Wisconsin, where if all cows are not contented they are hard to please. It’s a section as sleek as its cows, where life has a very high butterfat content. The farm Atherton chose is near New Glarus, in Green County, a town settled in 1845 by Swiss from Glarus, Switzerland.

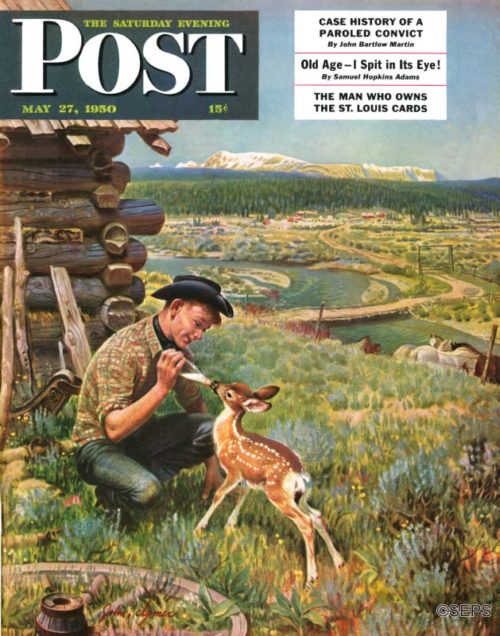

Feeding Fawn Near Flowering Field

John Clymer

May 27, 1950

Boys everywhere have pets; this variation of the pleasant practice is taking place in Wyoming. John Clymer kindheartedly omitted from the landscape the typical haystacks with ten-foot fences around them to persuade horses, cows, elk and high-jumping deer to go elsewhere in search of meals.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’m sure that many of your readers (unless they read the full caption) will not understand the significance of the split cover. ….and, as many Hawaii natives, like myself, surely feel, WE GOT GYP’D! Alaska has it’s own cover, and we’re the only one of the 50 that has to share billing!

suggestion: not to late to rectify that situation! ….I have some suggestions.

aloha,

Wally

Reminiscing of what was and some of what still is, represented in the Saturday Evening Post; many amazing artists illustrated life in America’s fifty states. The legacy of truth, tolerance, opportunity, and so much more has been gifted to us through their artwork.

That is an excellent observation. While we love celebrating the history of The Saturday Evening Post, we are acutely aware of the lack of diversity on the covers and in the pages of the magazine. You put it well when you said that the Post reflected “prevailing American ethos of the times.” We can’t go back and redo our magazine’s history, but we hope to offer more diverse perspectives in our current issues.

You caught us! It was difficult to find a cover devoted to each state. Note that Hawaii had to share its cover with Alaska.

I have a home on the Ohio River and that is a fair representation of today. The barges still travel the river loaded with coal. Can someone buy a copy of a cover?

Terrific! Enjoyed the beautiful pictures and interesting remarks. Will definitely be sharing with family and friends!

Even after these many years he still captured an enduring look at each state !

Couldn’t help observing that Ohio and West Virginia have the same picture location.

Really enjoyed this. Couldn’t help noticing that the Ohio and West Virginia pictures are the same spot.

Thoroughly enjoyed this, and shared it with friends and family. Thank you for helping make this a lazy Saturday morning!

Lovely display, enjoyed them all

Fascinating and nostalgic “tour” through the fifty states! But I was struck by something: the almost complete absence of ethnic minorities on these covers. We did see some Pacific Islanders on the Hawaii cover. There “MIGHT” have been some distant Negros on the Louisiana and Arkansas covers. But the overwhelming impression is of a Caucasian America. Now don’t get me wrong: I’m not going on a political correctness crusade here. I’m just observing how the Post reflected the prevailing American ethos of the times. Ethnic minorities were largely invisible, somewhere off on the sidelines. Not a condemnation: just a recognition of how much we have changed as a nation…

I guess the Ohio river has moved to West Virginia? Oops!