The score of a film is unlike a hit song. A movie score is in the background of the action — and usually instrumental. It sets the tone of the film without calling too much attention to itself. Film composers like John Barry, Ennio Morricone, and Henry Mancini made careers for themselves by creating rich soundscapes for cinema of every genre. Comprehensive orchestral training was requisite for composers in Hollywood for many years, but, increasingly, tinseltown has been importing rock and pop musicians to write scores.

There is a history of pop music in movies, but film collaborations from members of Radiohead, Daft Punk, Nine Inch Nails, and Arcade Fire in recent years are blending the mediums like never before. What possesses these rock stars to step out of the spotlight for the more concerted — and sometimes grueling — process of film scoring?

It could be the prospect of artistic growth. Graeme Thomson covered the rise of rock stars in movie music in The Guardian in 2009, venturing, “Although there’s next to no money to be made in writing for film, and all along the line the musician’s vision is subordinate to that of directors, editors and producers, the chance to be a mere cog in a much larger machine seems to offer welcome relief from the essentially solipsistic nature of songwriting.”

Just as a writer desires a prompt, artists of the indie rock world might crave boundaries for their creative instincts. Sometimes the results are groundbreaking.

Trent Reznor won an Oscar for his part in scoring The Social Network in 2010. The lead singer of Nine Inch Nails is known for a gritty brand of heavy rock, but his compositions for films like Gone Girl and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo are more subdued and electronic.

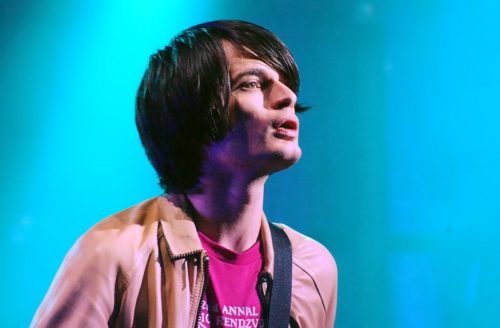

Jonny Greenwood, lead guitarist of the Grammy-winning band Radiohead, has scored several of offbeat director Paul Thomas Anderson’s films. Greenwood started composing for Anderson in the 2007 film There Will Be Blood. Greenwood’s score is an unsettling and, at times, sparse and dissonant accompaniment to Anderson’s film that the New York Times has called the best film (so far) of the 21st century. Greenwood has scored all of Anderson’s films since: The Master, Inherent Vice, and the forthcoming Phantom Thread.

Reznor and Greenwood have garnered significant acclaim for their efforts, but reactions to musicians in the film industry haven’t always been so positive — particularly from career composers. In the ’90s, highly trained orchestrators bemoaned that film scoring was being taken over by amateurs. Many new to the field were missing out on important musical training due to new technologies that rendered comprehensive craftsmanship unnecessary. “And it’s the absence of those skills that many movie professionals believe is the primary reason for a paucity of good film music now,” lamented David Mermelstein in a 1997 article from the New York Times. In Mermelstein’s article, Jerry Goldsmith, composer of scores for Chinatown and Patton, joined several other Hollywood music greats in denouncing the “preponderance of dilettantes and sophomoric people in the business,” but they felt that real talent would ultimately win the day. Has it?

The popification of film scores can be traced back to the ’60s. Mike Nichols pioneered the mixing of popular music with cinema in 1967 with The Graduate. Nichols used Simon & Garfunkel’s folk tunes as a soundtrack to his coming-of-age film about disillusionment and isolation. This practice was brand new at the time, and it paid off: The Graduate was one of the highest-grossing films of the 1960s.

Afterwards, musicians trickled into the industry. Hans Zimmer was associated with several early new wave bands including The Buggles and Krisma before turning to films. Today he is best known as the prolific scorer of dozens of movies, including Pirates of the Caribbean and The Lion King. Tim Burton collaborator Danny Elfman got his start in Oingo Boingo, the eclectic group behind the songs “Dead Man’s Party” and “Weird Science.” Tunesmith Mark Mothersbaugh started in the cult ’80s group Devo. Mothersbaugh has collaborated with Wes Anderson on Bottle Rocket, Rushmore, and The Royal Tenenbaums in addition to his work in many family movies like Halloweentown, Hotel Transylvania, and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. He has even scored several popular video games, namely in the Crash Bandicoot and Sims series. The ’80s and ’90s pop interlopers mostly left their groups for Hollywood pursuits.

These bandmates-turned-maestros signaled a shift in movie music, but it might not be the end of orchestration as we know it. Jon Burlingame teaches film music history at University of Southern California, and he’s been following Hollywood music trends for years. New music technology continues to give rise to original voices in cinema, and Burlingame believes this is good for the industry. However, he says, “There is an advantage to working with a composer who has a big toolbox. You should never count out the level of experience already in Hollywood.”

Composing a film score is still very different than writing a pop or rock song. According to Burlingame, the film composer’s task includes making music that underscores the emotion or drives the action or provides a musical counterpart to the location or time. He says, “These can be challenging prospects for someone who hasn’t worked in film before. You absolutely have to have a dramatic sense. Sometimes it’s an instinct; sometimes you can learn it.” Whatever that dramatic sense entails, it seems that the rock stars are learning it.

See our recent interview with film composer Hans Zimmer from the November/December issue.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Siteniz cok Guzel Konularnz Takip Ediyorum Tesekkr ederim harikasiniz.