This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

Originally published December 3, 1966.

The morning sky was clear over the South China Sea, but the weather turned murky as we approached the coast of North Vietnam. Our group of four Skyraiders had taken off from the USS Ranger 45 minutes earlier — at 9:00 last February 1 — and we were flying in formation at 10,000 feet.

All at once, flak appeared as noisy smudges nearby. Then in my headset, I heard a pilot shout, “I got a target. There it is at nine o’clock.” I looked down and saw it — an anti-aircraft battery at a road intersection. I pulled the stick, rolled on my back and started into my dive.

Suddenly boom, boom, boom. A 57 mm shell knocked off part of my right wing. Another burst hit my engine. It sputtered and quit. I shouted, ‘‘Mayday! Mayday!” into my radio. I leveled out and aimed at the target quickly, then dumped all my ordnance. Miraculously, I hit the target. The anti-aircraft battery had gotten me, but I knocked it out.

As I came out of my bombing run I knew I was going to crash. The plane was hardly controllable, and the jungle flashing past beneath me was getting closer. The only clearing was less than 300 feet long, and the surrounding trees were about 150 feet high and 3 feet thick. I pulled back a little on the stick, and the plane began to shudder. I hit a tree, and my right wing sheared off; the plane veered wildly as my left wing hit another tree. The fuselage flipped over two or three times. There’s no padding at all in the cockpit, but I was strapped in tight. I lifted my legs and put my hands in front of my face. I must have been knocked unconscious during the crash, because I remember only struggling to open the jammed canopy and then being on my back 100 yards from the plane. A big plume of smoke was rising into the sky.

I tried to get my senses together. My knee was blue, and it hurt like hell. My Mae West [life jacket] was gone, my helmet was gone, and blood was running down my neck. My first thought was to get far away from the crash. I crawled across a little creek and must have traveled about half a mile when I heard voices. I hobbled into some bushes, and slowly the voices faded away. I broke off some little sticks and bound them to my knee with elastic bandages to make a splint. Then I started crawling away on my belly.

I knew my target had been in North Vietnam very near the Laotian border, but I didn’t know where I had come down. If I headed east through North Vietnam I might reach the ocean. But then what? I didn’t have a signaling device anymore, so nobody would pick me up. But suppose I went the other way, to Laos? The jungle there would be thicker and easier to hide in. I still had my compass, and I decided to head west.

For the rest of the first day, I kept walking, avoiding trails and clearings and occasional animal traps. That night I slipped into my sleeping bag. At dawn I started moving again, and soon I got careless. Back in the States, they’d told me “always avoid clearings, trails, and water holes.” Now I said the heck with that. Why should I walk in the bush when the trail is easy going?

They caught me 15 minutes later. A couple of guys jumped out of the bush. “Ute, ute,” they shouted. I guessed they were Pathet Lao troops — pro-communist Laotians. One of them held an M-1 at my head while the other searched me. They tied my hands and hit me in the head a couple of times with their fists. Then they took away my watch, my compass, and my ID cards.

For the rest of that afternoon, they ran me along the trail. About 5:00, we reached a clearing where they tied me to a tree. Then a pleasant-faced man in a brown uniform walked over to inspect me. He had a red star on his belt buckle, so I figured he was the leader. The guards had given this man my Geneva Convention card and my regular ID card, and he was trying to read them upside down. For a moment I had a crazy impulse to laugh. But four or five guards had rifles pointing at me.

The officer and his men talked for a while. Then they drove big stakes into the ground and spread-eagled me between them. I spent the night trying to shoo away the mosquitoes by moving my head. Then the leeches started crawling up my legs. A leech is about as long as a needle and not much thicker. Sometimes when it drops off, it’s sucked so much blood that it’s thick as your little finger. Then you just continue bleeding.

or the next several days we walked, four or five guards in front of me, another four or five behind me. The trails twisted up and down so many hills that we had to zigzag constantly in the relentless heat. Occasionally we stopped at small villages. Men, women, and children came out of their huts and clustered about me. The men wore loincloths, and some of them carried knives. They screamed at me and waved their fists, and I could see hate in their eyes.

On the afternoon of the fifth day, we went into a huge cave where soldiers were milling around some Russian jeeps. For the first time since my capture, I was able to communicate with someone. One of the Laotian officers started speaking French. At first he was friendly. He had a camera and took my picture. For nearly a week I’d been eating nothing but rice. He gave me some sugar and a couple of eggs, and he told me that I could write some letters. Then he pulled out a piece of paper and asked me to sign my name. It was typed and phrased in perfect English and it said, in effect, that the Americans were dropping bombs on innocent women and children and that, although I personally opposed this policy, I was forced to fly on these missions by the U.S. government. I wouldn’t sign that paper.

The friendly officer said something to the guards, and they beat me on the head with bamboo sticks, then pummeled my face and ears with their fists. Next morning, the officer shoved that paper in my face again. When I refused to sign it, he told the guards to bring a water buffalo to the mouth of the cave.

They tied my hands, then my feet, and ran the rope 15 or 20 feet to the buffalo’s collar. Laughing, they prodded the animal until it trotted. I was dragged headfirst over sharp roots sticking out of the trail. My clothes were tattered; the skin on my legs was shredded, and I was bleeding a lot. I got madder than hell and called them a lot of dirty names. Then I passed out.

Finally, on the morning of the 14th day, we reached the prison camp — it was just a collection of bamboo huts sitting on stilts about four feet high. They shoved me into one of them, clapped handcuffs on my wrists, and stuck my feet into wooden blocks that must have weighed 30 or 40 pounds. It was very dark in there, but the door was open about half a foot. I saw six other prisoners in another hut a few feet away. Several were in bad shape. I could see big sores on their bodies. I shouted to them, and right away a guard came and told me to shut up. When he left, I called softly to the other hut. One guy called back that his name was Duane Martin; he was an Air Force lieutenant, a helicopter pilot, and he had been captured nine months earlier. Some of the others had been there more than two years.

They were really interested in news from outside. What did cars look like now? What was happening in Europe, Cuba, and China? What could you see on television? I told them that President Kennedy was dead. Duane Martin had said that, too, but they hadn’t believed him.

After a week I was moved into the other hut. Until a month ago, the prisoners said, conditions hadn’t been too bad. They’d even been allowed to boil water at night. Then Little Hitler came and everything had changed.

I’ll never forget that guy. He was short — about 5 feet 2 inches — and he wore a blue-and-yellow loincloth. He had dark skin, little squirrelly eyes, and a big belly. He always carried a submachine gun. He did his best to torment us, and he succeeded lots of times. He knew, for example, that we wanted water desperately, so he’d bring some in a pot and place it just out of our reach. Then he’d pour the water on the ground and laugh. Another of his tricks was to stand one of us in footblocks outside the hut and take the man’s handcuffs off. Then he’d tell the other guards that the prisoner refused to wear handcuffs and should be punished. Right away they’d beat him and fire bullets at his feet.

Of all the guards, and there were 10 or 15 at all times, Little Hitler was undoubtedly the worst. Still, he had competition — Crazy Horse, for example. He really did have a face like a horse, and he really was crazy in a brutal way. Then there were Sot and Dam and Windy — he was a sly son of a gun who was always sneaking around corners, trying to catch us doing something. And Jumbo — I shouldn’t forget him — a fat, dreamy-faced guy who didn’t care about anything. It was hot as hell during the day and bitterly cold at night. Nobody had a match or a lighter — we just rubbed bamboo together to make fire.

One morning — I think it was eight days after I was brought to the camp — Crazy Horse entered our hut with a big smile. We were going to be set free, he said, free to go home. We just had to walk to another headquarters.

We started marching. All of us were stumbling along, tied to one another by handcuffs. We should have known that Crazy Horse was lying. We didn’t reach a headquarters, only another prison camp, like the first one but more heavily fortified.

Now we settled into monotonous routine. Every morning we’d wake up with the chickens. One guy would holler, “Kopa-tie-a-chow” — I have to go to the latrine. There was a hole in the ground 30 or 40 yards away. Five or six guards would remove his footblocks and escort him there. But if he stayed there longer than half a minute, the guards would start shooting. We soon decided it was safer to relieve ourselves in bamboo containers inside the huts. One of us would have to empty these containers every second or third day and would run the risk of being shot — but this was better than having all of us shot at every morning.

At about 9:00, the guards would give us rice. Sometimes all seven of us would be allowed to eat this morning meal at a table outside the main hut, and we’d have about 10 minutes to talk before the guards yelled “Kuo-kuo” and shoved us back inside. During the day, the heat was so unbearable that the guards not on duty simply went to sleep. In mid-afternoon they’d wake up, go out to check their traps for animals, and look for edible leaves and bark. Around five they’d let us out again for another 10-minute meal before putting us back in footblocks for the rest of the night.

The most nerve-racking part of the routine was the singing. Every night the guards would sing the same propaganda songs, over and over. Now and then the guards would push us out of our huts and hang us upside down from trees or shoot bullets at our feet. One time a guard put an M-1 to my head, and I thought he was going to pull the trigger. Then he laughed and took it away.

After the first few weeks at the camp, we developed a routine of our own. Saturday night was our hoot-and-holler time. We tried to pick songs that all of us knew. On Sunday mornings we’d hold church services. We didn’t have a Bible, but some of us remembered Scripture, and we’d talk for an hour or so about God. Then we’d pray. The rest of the week we had nothing to do but sit inside those huts and wait for food or punishment.

Initially we had enough rice. Then, in March, about a month after we moved to the new camp, the food supply dried up. Once every four or five days the guards would go to check their traps. If something had been caught, it had probably been dead for a while; other animals had torn off its legs or head. For some reason, when they caught a pig, the guards would stick the raw meat into a bamboo container and let it rot there for several days. Maggots would crawl all over it, and it would stink so bad that the guards would hold their noses. But we never got sick from eating it. Most of the prisoners were already used to eating intestines, testicles, and eyes. I thought they were crazy at first, but after a while it didn’t bother me either. At mealtime, we’d take turns dipping coconut shells into a pot of cold food brought by a guard. If we had meat, we’d cut it up first to make sure that each of us got his fair share. One afternoon we found a frog under the floor of our hut. We divided it, raw, among the seven prisoners, and I got his heart. It was smaller than a watch stem, but at least it was food. At night the rats came. We caught them in traps baited with rice. The rats were very good eating. We’d cook them to the extent of searing off their fur, then eat the head, legs, tail, skin — everything. The snakes that we caught were small, but most of them had rats in their stomachs. That was a double feast.

We never had any medical attention. One of the prisoners had a badly infected tooth; pus was streaming out, and it hurt him a lot. He found a nail somewhere, placed it against his tooth, and hammered it with a rock. He chopped it off piece by piece, and that relieved the pressure. We all had diarrhea. We ate charcoal, and that would stop it a little bit, but some guys still had to defecate 20 or 30 times a night. Ants and bugs were crawling all around, and I can’t describe the smell.

There were times when I didn’t want to wake up. I figured the war would last another five years; I’d probably die anyway, so it wouldn’t make any difference. I knew I’d never get home.

From the beginning, we all talked about escape. We decided to wait for the rains which would begin in May. One of the guys made a crude calendar and scratched off the days with a piece of charcoal. D-Day was to be my birthday — May 22. That planning gave us hope and kept us alive.

In March, we started hiding rice in bamboo containers stashed above our heads. Now and then we picked up empty ammunition clips that the guards had discarded and stored them inside our huts. We rubbed bamboo together to make fire, heated the clips until they were soft, then pounded them with rocks into little knives. I tore up part of my sleeping bag and made a rucksack; another guy made a rucksack out of his shorts. I can’t describe the method we used to free ourselves from the footblocks and handcuffs — that information is now being given to other pilots — but I can say that by April we had perfected our technique. The guy who had the calendar kept crossing off the days.

But the rains didn’t come in May. The rice supply was almost gone; the guards caught fewer and fewer animals in their traps, and they began to get hungry too. In June we learned that Little Hitler had told the other guards that if they shot us in the back and dragged our bodies into the bush, they’d have all the food to themselves.

Now we couldn’t afford to wait for the rain. Our only chance for survival was to break out right away and try to make air contact. The guards were letting us out of the huts to go to the latrine once a week; our muscles were so stiff that we could hardly walk. If we delayed the escape any longer, we’d be much too weak.

About 5:00 each afternoon, the guards would walk to the kitchen, pick up their food in turtle shells, then walk back to their hut. Suppose one of us could wiggle through a hole in the floor of the hut and drop to the ground 3 feet below. He might be able to burrow under the 10-inch logs which surrounded the stilts and sneak across the open space to the guards’ hut. If he could grab a weapon, he could hold them up when they returned from the kitchen.

We didn’t have much time. I carved a hole in the floor of the hut, dropped to the ground, and dislodged one of the 10-inch logs with a rock and a bamboo stick. Another guy cut a hole in the wall so he could watch the kitchen. We didn’t have watches, but we could time ourselves by counting “one potato, two potato, three potato.” How long would it take us to get our knives and rice supply and rucksacks out of their hiding places? How long for us to get out of footblocks and handcuffs? How long for me to sneak out of the back of the hut, crawl across 15 yards of open space, and snatch a weapon? The guy with the charcoal added it up. Two minutes and seven seconds, he said.

The food supply was so critical that Little Hitler, Crazy Horse, and three or four others went to get rice in a village a few miles away. Only 10 guards remained. When the guards went to eat, I crept underneath our hut, edged past the logs again, and dashed across the open space. Two minutes and seven seconds — exactly what the guy had predicted. As soon as I reached the porch, the other prisoners started coming through the hole. I grabbed two M-1s, a carbine, and a couple of Chinese rifles. I loaded them quickly, passed them out to the other guys, and turned to face the kitchen.

All of a sudden, bang, bang, bang. The guards were running out — really coming at us. I felt the bullets fly by my head. We yelled, “Ute, ute” for them to stop, then returned their fire. Seven guards fell dead in their tracks. Three of them fled into the bush.

None of us had been hurt in the exchange of fire; still, we were in trouble. We knew there was a village only a mile or so from the camp. If these three guards had gone to get help, search parties would be after us in half an hour. We had rifles and machetes. Now one guy went back to the hut to get our signaling devices, rucksacks, and food.

Five minutes later we were moving out on the trail. Duane and I knelt down to pray. “Dear God, please let us get home. Help us now because we just can’t do it by ourselves.” Then two of the guys headed east, and we never saw them again. The other five of us walked south to the closest ridge. My feet were swollen and bleeding.

We spent the night near a creek. It rained, and leeches swarmed all over our bodies; we were too exhausted to care. We got up again at dawn and decided to split into groups of two and three. Duane and I would stay together. We gave the other guys 24 rounds of ammunition in return for one of their machetes. Then we shook hands and wished them luck.

We had no idea at all of our position, so we decided to follow the creek. It was rising now because of the rain; in some places it was only 5 feet wide; in others, more than 100 feet and very deep. On the third or fourth day, we built a raft of banana trees. It took us eight hours. We floated along for several hundred yards. Then we heard a waterfall. We jumped and swam as fast as we could to the shore. The raft swept over the falls and splintered.

We still had our machete, but we didn’t dare cut a trail. If we couldn’t go straight through a section of bush, we’d go around it or try to bend it or crawl under it on our stomachs. My arms were numb. The skin had been ripped from my feet and legs, and I could see bone.

Both of us were so damned weak. We kept passing out. At night we’d put our arms around each other and hug each other just to keep warm. We realized now that we might not make it. I promised Duane that if I ever got out, I’d visit his wife and family. He said he’d do the same for me.

Then Duane got malaria; his fever was very high, and he couldn’t walk. I helped him along, and finally we came to a deserted village. I laid him in a hammock. We were too weak to walk. Our food supply was almost gone, and our clothes were ripped to shreds. We didn’t have strength enough to carry our weapons and ammunition, so we had left them in the bush.

Next morning — this was the 14th day after our escape — I left Duane in his hammock and went back into the bush to find the ammunition we had discarded. I slept in the woods that night and then crawled back to the village. Duane was still there. And this was the greatest thing. He laughed, and I laughed, and we hugged each other. He was so happy that I’d found three rounds of ammunition, and I was so happy that he was still alive. We broke off the tips of the bullets, poured out the powder and rubbed the bamboo sticks together. Pffft — at last we had fire.

We boiled some leaves and tapioca; it was the first hot meal we’d had in months, and it really cheered us up. We kept the fire going then and tied some rags to bamboo sticks for signaling devices.

Late that night, we heard a plane. It circled over the village and dropped a couple of parachute flares. “Hey, he saw us,” Duane cried. “He’s gonna get us in the morning.” We stayed awake all night talking about what we’d eat tomorrow.

The plane never came back. We waited all that day before giving up. At dawn next morning — the 17th day after our escape — we stumbled away from the village. Suddenly, a black-haired guy in a loincloth started running toward us. He carried a long machete — curved at the end. “Amerikali, Amerikali,” he yelled. We nodded our heads and mumbled, “Sentai, Sentai” (“hello, hello”). But the man kept running. I jerked back and tried to stand up.

His knife was already moving through the air. Thuk, thuk. The first blow hit Duane on the leg; the second cut into his shoulder just below the neck. He screamed, and I threw up my hands as if to say “No.” I knew Duane was dead, but I couldn’t grasp it; I just stood there with my mouth wide open. Then he swung at me. The tip of his knife missed my throat by half an inch. I don’t know where I got the strength, because I moved, man, I really moved. I turned around and hit that bush and ran up a gully, and my legs didn’t hurt anymore.

That night I crawled back to the village. I thought it was their village, and I wanted to burn it down. I was angry and a little bit off in the head. I sat in front of a fire and threw everything on it. I didn’t care if they caught me.

Then I heard a plane. It circled over the village and dropped about 20 parachute flares. Next morning I waited and waited, but the plane did not return. “God,” I said. “What’s the matter with those guys?” I knew they wouldn’t save me now. I picked up one of the parachutes and tore the panels out. That afternoon, I crawled up to a nearby ridge. I saw a little hut there, and I said, “That’s where I’m going to die.” I prayed. “God, forgive me for the bad things I’ve done in life. I just can’t fight it anymore. Please let me die. I don’t want to wake up.”

But I did wake up. I was really thirsty, and I said, “To hell with it. Those guys aren’t gonna lick me.”

I stuffed the parachute panels into my rucksack and fell down the ridge. The skin had ripped off my feet and they were just bones. But there was no particular pain. I thought of all the things I’d missed. I wanted to go deep-sea fishing. I wanted to ski and build a chalet in the California mountains, and I wanted to buy a Porsche. All these hopes were gone. I remembered that once — back at Lackland Air Force Base six years before — I had thrown away a piece of bread. I swore that I’d never do that again.

Next morning — this was the 22nd day after our escape — I took the parachute panels out of the rucksack, tied them end to end and laid out an SOS by the river. I wrapped another panel around a bamboo stick. Then I passed out again. When I came to, I thought I heard a plane. I gathered all my strength, started waving that bamboo stick and — zoom — the plane was past me and gone. But he came back several times and wiggled his wings. I was so happy that I started crying and shouting and rolling around on my back. Then I collapsed.

Suddenly I heard the helicopter, 200 feet above my head. The steel rope began falling slowly toward me. And there was the rescue harness; a slender device with three little arms folded into its side. I had to press the arms down to make a seat, but I couldn’t unzip the plastic cover. I clawed at the harness and finally wrenched one arm free and gave a little signal. I was hanging sideways; I didn’t know if I could hold on much longer. I said, “God, don’t let a bullet hit me now. Not after all this hell I’ve been through.” Then I saw a leg and green pants standing in the chopper door. An American leg! I grabbed onto it and cried.

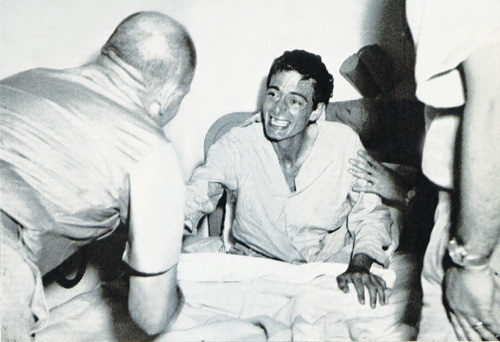

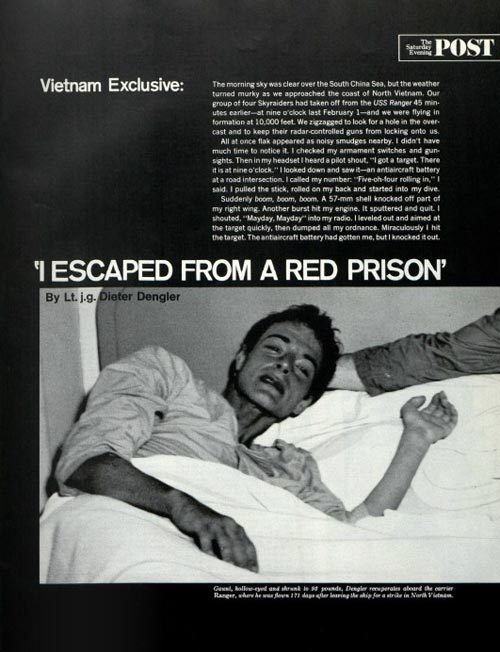

I went back into shock at the hospital in Đa Năng. I weighed only 93 pounds. I couldn’t move my arms or legs or head. Yet everything was pleasant and nice. I thought that this was all a dream; I thought this was how it was after death.

Back in San Diego they treated me for kidney disease and liver disease. They fixed my teeth, and when I got malaria — right there in the hospital — they cured me of that as well. At first, I had to sleep on the floor; a bed was just too soft. I had lots of bad dreams, too, and I’d wake up three or four times a night sweating and screaming and yelling.

The doctors say I’m doing pretty well now. I weigh about 150 pounds, and I’ve got as much energy as anyone else. I still have some ringworm on my feet; there are a couple of bugs inside me that they have to take care of, and I’m losing all my hair. I feel pretty bad about that, but they tell me that it will just be temporary.

Anyway, my fiancée doesn’t seem to mind. We flew to Reno in early October and got married, and I have to admit I’m pretty happy about that. In a few more weeks I should be able to fly again. That will make me happy too.

—“I Escaped from a Red Prison,” December 3, 1966

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now