This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

It took vision (and money) to replace the network of narrow, unsafe roadways originally designed for horse-and-buggy travel with the wide, safe concrete thoroughfares we take for granted today.

—Originally published April 16, 1955—

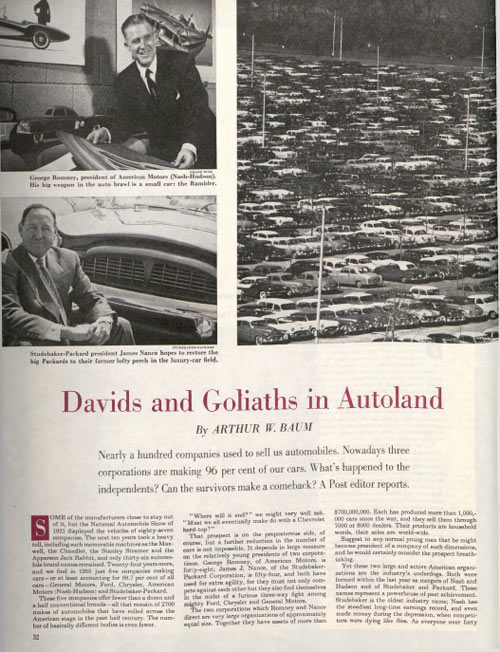

The National Automobile Show of 1921 displayed the vehicles of 87 companies. The next 10 years took a heavy toll, including such memorable machines as the Maxwell, the Chandler, the Stanley Steamer, and the Apperson Jack Rabbit, and only 36 automobile brand names remained. Twenty-four years more, and we find in 1955 just five companies making cars — or at least accounting for 99.7 percent of all cars — General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, American Motors (Nash-Hudson), and Studebaker-Packard.

These five companies offer fewer than a dozen and a half conventional brands — all that remain of 2,700 makes of automobiles that have rolled across the American stage in the past half century. The number of basically different bodies is even fewer.

A further reduction in the number of cars is not impossible. It depends in large measure on the relatively young presidents of two corporations. George Romney, of American Motors, is 48; James J. Nance, of the Studebaker-Packard Corporation, is 54, and both have need for extra agility, for they must not only compete against each other but they also find themselves in the midst of a furious three-way fight among mighty Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors.

The two corporations which Romney and Nance direct are very large organizations of approximately equal size. Together they have assets of more than $700 million. Each has produced more than 1 million cars since the war, and they sell them through 7,000 or 8,000 dealers. Their products are household words, their sales are worldwide. Yet these two large and active American organizations are the industry’s underdogs. Both were formed within the last year as mergers of Nash and Hudson and of Studebaker and Packard. These names represent a powerhouse of past achievement. Alas, people do not buy automobiles because of an old name, an excellent earnings record, past glory, or present race-track results.

In 1952, Nash, Hudson, Studebaker, and Packard, as separate companies, all made money. Three of them managed a profit in 1953, although by the end of that year the automobile climate had changed materially. Ford was pouring automobiles onto the market in an effort to overtake Chevrolet. Chevrolet was matching the flood in order not to be overtaken. Retail dealers in most lines were taking short profits and in many cases shunting new automobiles directly onto used-car lots to be sold at discounts.

The new and hard competitive times extended into 1954 with further results. In 1954, with the exception of Ford and three General Motors cars, every make of American automobile suffered a decline in sales. This was not altogether unexpected. Nobody thought the postwar sellers’ market would last forever. In fact, Nash and Hudson, and Studebaker and Packard were preparing for heavier competition by negotiating their respective mergers.

It was an unfortunate time to undergo the inevitable production interference of putting corporations together. By the end of 1954, each of the newly formed combinations had dropped 70 percent below their component models’ best postwar year. Whereas in 1950 the four companies had enjoyed better than 10 percent of the national market, in 1954 the two merged companies obtained less than 4 percent.

There is a saying in Detroit that once a manufacturer starts down he never comes back. It is not always true. But for the hundredth time in automotive history the question was asked, “What is going to happen to the independents?”

The underdogs were not visibly intimidated. They prepared for a sales war in 1955. But Detroit comments were far from unanimous on how far, how soon, and if ever they would swing up again. One thing they certainly possessed was the Big Three’s warm wishes that the independents would recapture their normal share of the market — at the expense of someone else. The fewer the independents, the more the Big Three love them. The large companies are aware that they produced nearly 96 of every 100 cars last year, and that Ford and GM together produced 84 of the 96.

On the rejuvenation of the independents a cynic says, “They are trying to do it with mirrors.” A thoughtful big-company official says, “There is definitely a place for them, and I feel sure they will retain it.” An industry banker suggests, “They need to be knocked together into a fourth big company with a banking group in control.”

In all of this there is no question about Nash-Hudson and Studebaker-Packard making good automobiles. No one denies that they do. The worth of all current American cars is taken for granted. In a foreword to Ward’s 1954 Automotive Yearbook, the publisher of this industry authority makes it plain in one sentence, “With all cars today essentially well-built and well-engineered, style remains the one major point of distinction to the general public.”

It is into this kind of national market that both American Motors and Studebaker-Packard are charging with a good deal more force and resolve than any of their component companies have shown in years. It will not be difficult for them jointly to raise their share of the market above 4 percent. They must do so if they are to make adequate profits.

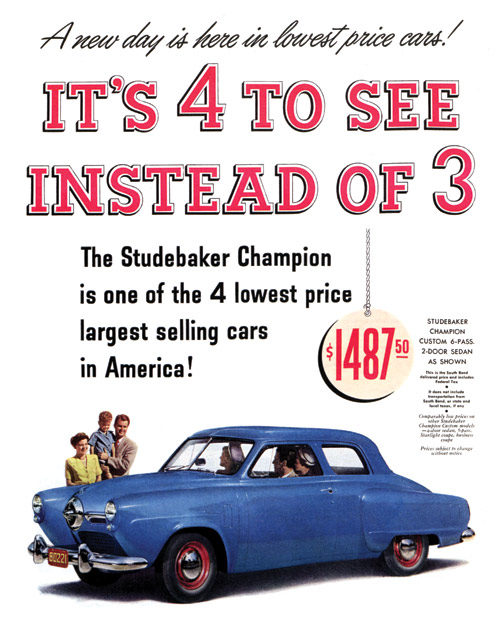

The two have one thing in common — they are both designed to chew into the large markets of the Big Three, as well as into each other. American expects to do this with a volume car, the Rambler, to support Nash Statesmen and Ambassadors, and Hudson Wasps and Hornets. On the assumption that it already has a volume car in the Studebaker Champion, the company is hungering for new business in the top areas of a full price range. It has its heart set on restoring the big Packards to their former perch in the luxury field, a rarefied neighborhood around $5,000.

It will be interesting to see how their economy package fares in coming seasons, because it is aimed at a commonly voiced complaint, the fact that the Big Three low-priced cars have become larger at a time when traffic is thicker and parking more difficult. Since the Rambler was launched in 1950, approximately 200,000 have been sold, and it should be much more salable in 1955. A previous handicap, low-hanging front fenders, has been removed by fender cutouts, giving the car a very short turning radius, and the steering equipment has been improved. Romney believes this turning ease will eliminate any need for additional owner investment in power steering, and that the car’s light weight will make power brakes unnecessary. The conception is that car buyers are becoming annoyed at the extras they must load on new cars. Romney thinks this escape from extras, plus the increasing value of maneuverability as traffic grows worse, will attract buyers.

The independents have long charged indignantly that big-company dealers deliberately poison customer minds about trade-in values of smaller-company products. It is to be suspected, however, that any actual weakness in the used value of independent makes, and this would also include some non-independent cars, can be laid to styling. Nash, for example, has had its share of inverted bathtubs on the market in the last decade, and Hudson has at times squelched its other virtues by body design seemingly two sizes too big for the frame.

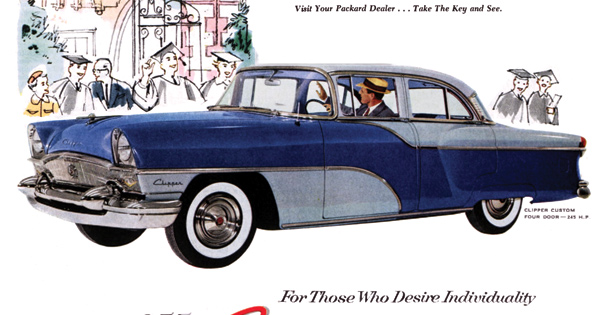

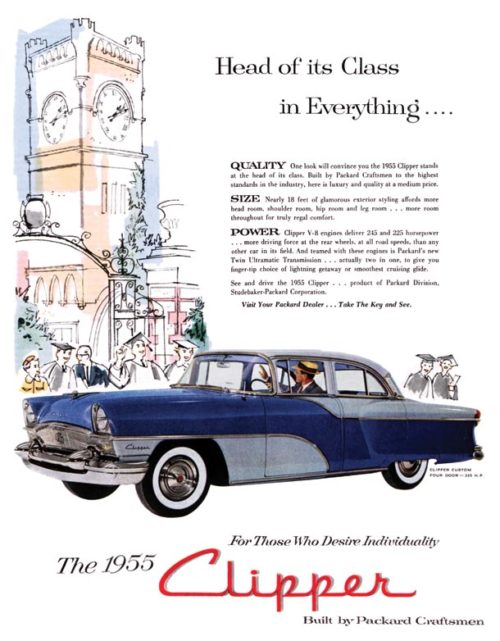

For Packard it was high time that something was done with the bearer of the famous name. For about 20 years Packard has been warming itself with scrapbooks relating the glory of the old Twin Six, but it has been living on inexpensive editions of the car that once was king. The lesser Packards, however, beginning with the Packard 120 in 1934, stole a lot of the big car’s prestige, as Packard officials are aware.

The Packards of 1955 have made distinct progress in design. Styling, which had been stodgy prior to 1951 and only moderately improved after that, has in the 1955 models put the big Packards back on the road as impressively modern cars, long and low. This style step-up may be of more importance to the line than a new suspension device which Packard is promoting as revolutionary.

In this era in which, admittedly, style sells automobiles, the case of Packard’s new companion, Studebaker, is a curious one. Normally the largest volume maker of the four corporations which have now become two, Studebaker was actually an industry style leader in the early postwar period. The company courageously led a decided advance in closed-car window visibility. Its reward was volume, and in 1949 Studebaker alone held a greater percentage of the national market than all the independent makes together in 1954. However, with equal style daring but opposite results, Studebaker threw away its gains on an abortive airplane-nosed design introduced in 1950 which helped start sales downward.

The costs of producing an automobile have, of course, been a major pressure behind the independent mergers, and their future success will rest on how well they pare the cost of producing each unit, as well as on increases in volume. The competition today is among push-button automatic factories and efficient assembly lines. Automatic factories and mile-long assembly lines make profits and build big companies only if they produce masses of salable automobiles. Romney estimates that maximum tooling and manufacturing economies require production of 160,000 to 200,000 automobiles annually.

Both American and Studebaker-Packard have their sights set higher than that, suggesting that if they fulfill a substantial part of their programs they will move ahead. And if public sentiment retains its traditional forms, they will, as underdogs, have on their side the friendly interest of a national audience that loves upsets.

—“Davids and Goliaths in Autoland,” April 16, 1955

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now