This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

This article and other features about the golden era of American cars can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, American Cars: 1940s, ’50s & ’60s.

— Originally published October 20, 1956 —

On last June 29, with President Eisenhower’s signature, one of the most astounding pieces of legislation in history quietly became a law. Public Law 627, known as the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, represents such a monumental conception of national public works that its accomplishment will literally dwarf any previous work of man. In addition to the size and scope of this heartening program to rehabilitate our major highway systems (heartening because here, at long last, America’s wealth and resources will implement a project to aid Americans), Public Law 627 is an inspiring example of democracy at work. Torn to pieces by partisan, sectional, and pressure-bloc attacks in one session of the 84th Congress, the legislation passed both houses of a subsequent session of the same Congress with but one dissenting vote. That should answer any questions, in any language, as to who really runs this country.

Though it is by now apparent that practically every American wants and is willing to pay for better highways, few of our citizens outside the highway agencies involved understand just how the new legislation will bring this about. Now let’s see what we are going to get for the approximately $50 billion in use taxes we shall be paying into the federal-aid highway program during the next 15 years.

he form of other public works — just take the Panama Canal, the Grand Coulee Dam, and the St. Lawrence Seaway and combine them into one tremendous construction project. You could finance 29 such projects with the money we’re going to put into our main highway system under this new legislation. Does 15 years sound like a protracted work schedule to you? It took the Romans 500 years to build the 50,000 miles of their famous single-lane highway system; in the Interstate System alone we’ll be building some 150,000 lane-miles of incomparably superior road in about 1/40th of that time.

George Hughes

June 15, 1957

© SEPS

As for employment — by 1960, when the program reaches its peak spending level of about $8 billion a year for new construction, there will be a labor force of 900,000 working, either directly or indirectly, on the federal-aid highways. This labor force, over the 15 years of the program, will utilize 439 million tons of steel, cement, and bituminous materials. Nobody, but nobody, can estimate how much dirt will be moved. If the crushed stone to be used for the base of the roads constructed under the new program were to be dumped in conical piles, you could form 500 pyramids, each the size of Cheops’ — four city blocks square and rising to the height of a 40-story building.

As this hog wallow of statistical superlatives suggests, the road-building program this country has planned for itself during the next 15 years creates a new concept of the word colossal. The projected improvement and reconstruction of our federal-aid primary and secondary systems is, in itself, an enterprise of staggering dimensions; this, however, is just another road-building job when compared with the task we have undertaken in preparing the Interstate System for tomorrow’s traffic.

That new title — the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways — tells the story of the road network which will receive the major portion of the brave new effort to get this country out of its national traffic jam. The Interstate System, first designated in 1944, is the 40,000-mile network of existing roads which comprise our trunk-line highways; it connects 209 of the 237 cities having a population of 50,000 or more, and serves the country’s principal industrial and defense areas. A defense area, in this respect, is considered a strategic production center rather than a military base.

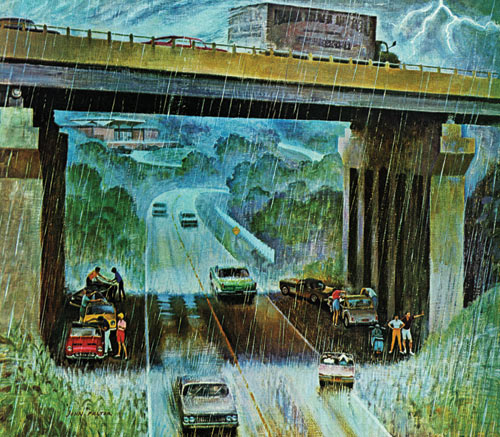

Though the idea of the Interstate System has been around for some time, the 1956 legislation, with a small phrase directing that local traffic needs be given an equal consideration with interstate commerce, has added an exciting new potential to the program. Spelled out, this means that the Interstate System will not only connect our major cities, it will also serve these urban centers with expressways which both bypass the built-up areas and tap the traffic sources of the city itself. This means that, for the first time, comprehensive planning and large gobs of federal-aid money are being thrown into the fight to solve our urban traffic tangles.

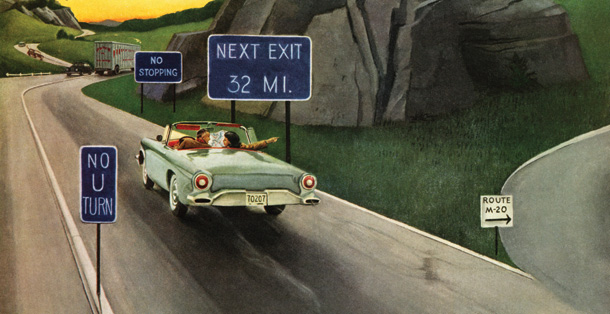

What sort of highways are we going to get for our money? The first fact to be noted is that the Interstate System will be built to accommodate our estimated 1975 traffic needs, plus a capacity for expansion after that date. In appearance, the roads of the new system will generally resemble the best of our present toll turnpikes. They will be broad ribbons of highways on rights-of-way varying from 150 to 300 feet wide, depending upon the terrain, the type of country, and the number of lanes involved. Most of these rights-of-way will be fenced in, and all will be reserved exclusively for highway use — which means there will be no billboards and none of the commercial development which flanks most of our present highway system. Service stations, motels, and restaurants will be located either on frontage roads which parallel the highway or on the intersecting roads which lead to the interchanges. Most rights-of-way will provide space for future expansion, making the system a reasonably permanent development.

The built-in design speeds of the new system — 50-to-70-mile-per-hour minimums in rural areas and a 50-mile-per-hour minimum in urban areas — call for gentle grades and slow curves. Legal speed limits will be set by the states. Traffic lanes will have a minimum width of 12 feet, and all-weather shoulders will be from 6 to 10 feet wide. The dividing, or median, strips on the multilane sections of the system will be at least 36 feet wide in rural areas and no less than 4 feet wide in built-up urban areas. Most of the access roads at the interchanges will merge with the traffic flow over speed-change lanes. Road surfacing will vary in several states, but all of it will conform to the highest standards of modern highway construction.

John Falter

September 15, 1962

© SEPS

This brings up the question of what will happen in the case of towns located on the present Interstate System. The answer is unequivocal: The new highways will go around them. Access roads, generally built with federal-aid-to-primary-roads money — 50 percent from Uncle Sam and 50 percent from the state — will angle out from either side of the town to the new highway. Economic studies have shown that such a bypass for through traffic invariably benefits a small town by easing congestion in its shopping and business centers. Where the access roads join the new highway, an arrangement of official signs will direct through traffic to the town’s service, restaurant, and motel facilities. The very fact that the bypass will be a controlled-access highway, with no commercial development on its right-of-way, will protect these existing highway-service businesses.

The two biggest problems facing the builders of the new system’s urban links are long-range planning and the acquisition of rights-of-way. Any reader can vicariously sample the agonies involved if he will take a map of a large metropolitan area with which he is familiar. Imagine the cost and effort involved in acquiring the 200-foot rights-of-way for this network and the engineering problems to be met in carrying local traffic over or under the expressways, and then compound the problems by introducing apparently endless delays occasioned by public hearings, material shortages, and litigation. This is the task which must be accomplished by our urban officials and our 48 state highway departments during the next few years if our cities are not to choke to death on their own traffic. The new federal program provides 90 percent of the money for this job, and also sets the time limit for its completion.

Though cutting traffic corridors through the hearts of our cities may at first seem like a horrendous economic waste, the experience of highway planners to date has proved that such developments actually profit every section of the urban community. Property holders on the expressway sites are paid a fair sum for their equities, while land adjacent to expressways invariably increases in value. Most important, the combination of the inner-city expressways and the belt lines enables the city to spread its former boundaries of convenience and creates new realty values in all directions. A happy byproduct of all these expressway developments is that they invariably do an excellent job of slum clearance as they knife through the poorer sections of the city.

The first bulldozer cut under the new program for the Interstate System was made on Route 40, near St. Charles, Missouri, on August 10, 1956. Massachusetts awarded its first contract under the new program on August 14, and Ohio began moving dirt on an interstate project in early September. The 15-year campaign to get our traffic moving is underway; with a little luck and lots of cooperation from everyone, we’ll be riding from coast to coast and from border to border without a stop light or a traffic snarl by 1972. The Automotive Safety Foundation estimates that, during its first 10 years of operation, the improved Interstate System will save 35,000 lives. Will you or your children be among that army of the reprieved? If so, you can count the time and the money the new highways will save as just another dividend.

— “Coast to Coast without a Stoplight,” October 20, 1956

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now