O

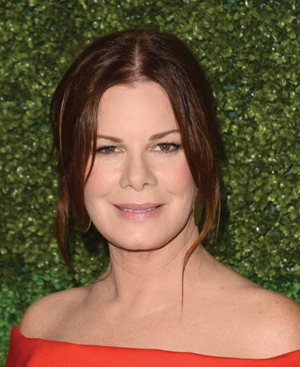

scar and Tony winner Marcia Gay Harden has thrilled audiences with her surprising range of performances on screen and on stage. She is proud that the emotions she’s shared in over 50 films — including Pollock, The First Wives Club, and Mystic River — reflect passion for her work and deep attachment to her family.

On TV, Harden plays Dr. Leanne Rorish, a key figure in the highly pressured life-and-death atmosphere of the E.R., on the popular CBS drama Code Black. She can be a tough and rough voice amid the chaos where seconds count and she must make flash decisions in a room full of pros who don’t always appreciate her style. In this third season of the series, Leanne decides to adopt a teenage girl. Harden knows that world too; three kids at home have taught her about teen push-back.

“They’re exploring a softer side of me, but I don’t really want her to become safe. It’s more fun to play someone who is slightly unsafe. What I liked was her cowboy attitude. I really like the badass side of her. Leanne can be a nurturing mother and still be as strong as she needs to be.”

Marcia Gay’s own nurturing and outspoken personality are now exposed off the stage and screen, in her first book. The Seasons of My Mother: A Memoir of Love, Family, and Flowers, is bold, funny, and sensitive. In it, Harden reveals the agony of watching her beloved mother, Beverly, suffer with Alzheimer’s.

Jeanne Wolf: It took strength for you to write about your mother as she weakens and also to share your own joys and struggles.

Marcia Gay Harden: I wanted you to laugh but also to cry. I thought, “You have to include your divorce, your mom’s Alzheimer’s, the deaths in the family. If you don’t, then it becomes everything you hate as an actress: about being cast in a bad role that has no real downsides or weaknesses.” I want my audience to relate to the moments when we’re not the hero — when we think we’re cowards. I think that’s what audiences relate about in me. I’m the toughest person on myself ever. My mother kept trying to teach me to be gentle and forgiving, mildly disapproving but never outright harsh. I couldn’t always live up to her image of what I should be because I liked to curse and drink and smoke. That’s who I am. And, I admit, sometimes I was a bully.

JW: You don’t hide your rage and frustration as you watch your mother suffer and you learn about her horrible condition.

MGH: Alzheimer’s is a thief, a cowardly thief because it sneaks in and steals your mind. With my mother, it was literally a realization that it could happen to anybody. She was the poster child of what to do not to get Alzheimer’s. She never drank, never smoked, ate well, exercised, was mentally active. I know now that Alzheimer’s lives in you 10, 20 years before it shows signs.

What affected me so much was the repetition of her forgetting. I could see her anguish as she would forget. The look on her face as I realized that she just wanted to have a sequence of moments strung together where she would remember what happened the few moments before. It was that realization that she’s not in control of her memory, and that was scaring her. It’s frightening because the disease leads you into abject loneliness. There are no survivors.

Now what I want to help do is create a world where there are survivors and research and a drug that allows you to live with the disease. We need to figure out what’s causing it and get rid of that.

JW: While you were facing your mother’s illness, your marriage was also falling apart. Your mother may not have understood what you were going through, but we can feel it on the pages of The Seasons of My Mother. You and the father of your children, Thaddaeus Scheel, were splitting up.

MGH: I decided that we would be friends for the kids — just because it makes sense. Like my mother says, “Filling your head with good, loving thoughts is a thousand times better than carrying on the animosity of loss.”

There were a lot of things I didn’t include in the book that I could have. What I really talked about was my hurt, and my ex-husband knew that our break-up was very painful to me. I always saw people who loved each other, but when the marriage fell apart, they forgot that they loved each other and turned it into hatred for the rest of their lives. But I realized it just doesn’t make any sense if you’re a parent. Try to remember what you loved and move on. Forgiving is a powerful thing to do, but it didn’t mean that I wasn’t in pain.

My children knew what was going on. I’m pretty straight up with my kids; I don’t waste a lot of time sugar-coating events. I think kids can handle truth far easier than we imagine.

As for being a single mom, there’s a lot to be said about being single. It’s really wonderful. I do have a hard time making time for other people because I’m lucky that I love my work and also love going home and making jam with my kids. There’s a part of me that I don’t really want to be sharing right now. I don’t really want to be in a dysfunctional relationship or think, “I can’t sleep because you’re snoring.” I like my single life, but I would open up to love. I think when you do open up to love, there’s a myriad of things that you find you can make room for, including, I guess, snoring.

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now