Years ago, I stopped to photograph in a Mayan village in Mexico, a place so small that it still isn’t on most maps. Rows of traditional thatched-roof houses lined both sides of the highway. It reminded me of an English village, each house behind a whitewashed drystone wall, except there were vivid tropical flowers and fruit trees in each yard.

A family offered to sell me a baby parrot. I put out my finger. The parrot climbed up, not stopping until it was nuzzling against my neck. I called him Suc Tuc, the name of the village. He would squawk when he wanted food. He squawked all the time. Every day I’d buy fresh ground corn masa. I’d pinch little bits into bite-size balls to put in his mouth, like a mother bird feeding her baby. As he grew, he started eating on his own. I added fruit to his diet.

He matured into a beautiful bird. Actually, that’s not entirely true. Even that young, he was more like a crusty little sidekick, a bit scruffy, and we traveled everywhere together. This wasn’t a bird that lived in a nice cage in a nice house. We were living in the jungle. I had long hair back then, and at night he would often crawl underneath it and fall asleep on my shoulder. When I spent a rainy season in the jungles of Quintana Roo below Tulum with a family of chicleros — the men who bleed chicozapote trees for chicle, the resin used to make chewing gum — I’d leave Suc Tuc on my hammock ropes every morning when I went out. I’d whistle for him when I returned, and he’d whistle back to let me know where he was.

Driving back to California in December, we hit cold weather. Suc Tuc crawled in my mummy bag with me when I camped at night and slept next to my head. I’d put a piece of paper under him so I didn’t have to clean the bag. I shoulder-trained him to jump off so he wouldn’t soil my shirt.

I got a job in construction so I could make enough money to return to Yucatán. In the spring, I was laying adobe brick on a large house. I brought Suc Tuc to work every day. Another worker brought his dog with him, a big St. Bernard. The dog pounced and then swallowed my parrot when he flew off my shoulder for a bathroom break. I jumped off the scaffolding, picked up the St. Bernard by his tail, and kicked him in the belly until he vomited my bird. Suc Tuc was covered in saliva, he had a puncture wound in his chest, and he was missing feathers, but he took one look at me and squawked the equivalent of “Mama!”

He lost so many feathers I put him in a box with a goosenecked lamp to keep him warm. He recovered but never flew again. I tried to un-train him not to jump off my shoulder, but he’d plop to the ground, poop, and climb right back up.

When I saw the red-tailed hawk lying dead on the road, I immediately pulled over. It wasn’t right that such a beautiful bird be reduced to a bloody stain of flesh and feathers, each successive set of tires pushing it further into the asphalt. I put her on the floor of the cab of my pickup. I pulled back onto the freeway, shifting gears until I was doing 70 miles an hour again. A few minutes later, in a flurry of feathers, the red-tailed hawk was standing next to me on the seat. I tried not to make any sudden movements. I raised my foot off the accelerator. If she attacked me, we were both dead because we were still going too fast if I lost control. Out of the corner of my eye, I watched her examine me. I could only wonder what she was thinking. One moment she was flying, the next finding herself inside my pickup. She had probably been stunned in a collision with a truck. It must have occurred right before I arrived because no one had run over her.

She stood next to me, watching the sky move past the windshield without a trace of wind or air currents. When she didn’t attack, I spoke to her in a low voice I hoped sounded comforting and reassuring. She looked at me appraisingly and somehow understood I was not a threat and we could share my pickup cab together until we arrived home.

I had a pair of welding gloves in the barn, and I put one on and held out my hand. Her talons were perfect crescents that came to needle-sharp points. She gently climbed on, gripping just enough to keep her balance. I hoped she was simply stunned and would be able to fly. I moved my hand up and down, enough so that she had to open her broad rounded wings to keep her balance. But she didn’t fly off.

We looked at each other. I told her she was a beautiful bird. Her chest was the color of a coffee stain moving to cream, her wings and back were dark chocolate, and she had cinnamon coloring on top of her head.

I went to the store and bought hamburger. I carefully fed her, wary of her piercing raptor’s beak. When I offered the first little ball, she delicately took it from my fingers. She didn’t lunge for it. It reminded me of feeding Suc Tuc when he was a baby. He was watching from the other side of the kitchen. I worried the hawk would think he was an appetizer if he was on my shoulder.

Parrots enjoy being scratched around the head, especially the nape of the neck. Scratching from behind, I would use my thumb and middle finger, and Suc Tuc would put his head down and ruffle his feathers. This is an area birds can’t reach when they preen themselves, so I was helping to groom him. He enjoyed it so much so he would duck his head and ruffle his feathers whenever he wanted me to do it.

I wondered if I could scratch the hawk’s head too. A bird is vulnerable when it puts its head down. Would she trust me enough to let me do it? I knew I shouldn’t try, but curiosity got the better of me. After feeding her, I slowly moved my hand behind her head. I lightly scratched the nape of her neck. She ruffled her feathers and lowered her head. I scratched harder and she lowered her head even more. I was in my kitchen, holding on my hand a wild red-tailed hawk I had just scraped off the highway. Instead of fighting, clawing, and pecking to escape, she was ruffling her feathers so I could groom her. I’ve only experienced trust like that with small children and animals. Each time reminds me I have to live up to it.

There weren’t any raptor rescue centers then like there are today, so I tried to rehabilitate the hawk myself. I also didn’t find any manuals on how to heal a hawk. This was decades before the internet. I had to come up with a plan of my own. I thought she would need to use her wing to strengthen it. I spent a lot of time working with her every day. She would hop on my hand whenever I put it in front of her. I kept expecting her to dig in with her talons, but she never did.

I bought some mice from a pet store and took the hawk out to the corral. My horses didn’t seem surprised, but they kept their distance. I put her on the top rail of the corral, then tied dental floss to a mouse with about 20 feet of lead, and tied that to a fence post. I let the mouse loose and hoped the hawk would try to pounce on it. It was lucky the mouse was tied up because she hopped around chasing it before she caught it. Day-by-day she progressed from falling to gliding to actually flapping her wings. I didn’t have to tie up the mice any longer.

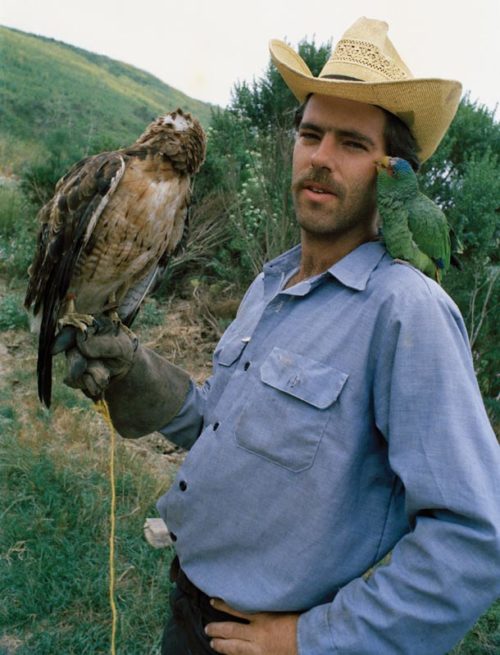

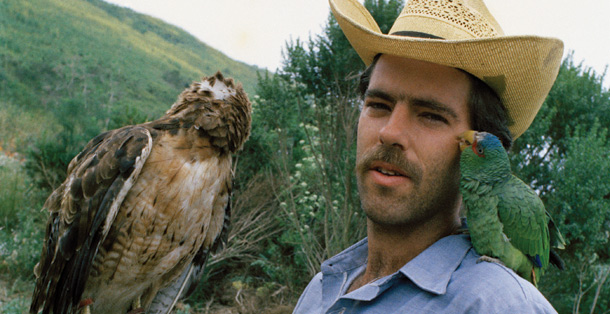

After a few days, I put Suc Tuc on my shoulder. I walked over to the hawk and put out my hand. She hopped on and looked at Suc Tuc with feral interest, not unlike the white mice I provided her at the corral. But she didn’t lunge for him, so I carried them both. Soon they both wanted attention. Suc Tuc would bend his head forward, ruffling out his feathers for me to scratch him. I’d rub his head until the hawk indicated she wanted attention. Then I’d switch and scratch her head. Suc Tuc would then busy himself grooming me, nibbling around my ear, but he never acted jealous of the hawk. We’d go for walks together. The barn was at the bottom of a valley, with hills rising on three sides covered in grass and brush. I wanted the hawk to spend as much time outside as possible and excite her to try to fly. We scared up jackrabbits that darted away while birds flitted around us. I wondered how long she would be content to move as slowly as I walked.

After about a month, she took wing and flew off. It was time. She needed to be wild. The first few days she would circle the barn and sit high on a branch in a eucalyptus tree on the hillside. Red-tails have a very identifiable screech, and I’d look up when I heard her, but then we both had our own separate lives to live and I stopped looking for her.

Of course I wished she would come back to visit. I dreamt I could whistle for her and she’d answer from high above and I’d put out my arm and she’d come swooping down to land on it. A red-tailed hawk is so thrilling to watch, soaring effortlessly, so regal, graceful, and beautiful.

It made me think of our relationships with wild animals. When people ask each other, “If you came back as an animal, what would you want to be?” many name a dominant animal in their environment, such as a lion, a tiger, an elephant, or a red-tailed hawk.

I don’t, and I’ve thought about it a long time. I want to come back as a canyon wren. They’re not that pretty, although they have the same rust coloring as a red-tailed hawk. But it has the most mellifluous and evocative song, like a cool trickle of water descending over rocks, a sweet cascade of falling liquid notes. It always puts me in a good mood. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to add beauty to the world every time you opened your mouth?

Macduff Everton is a photographer living in Santa Barbara, California, who photographed the Yucatán peninsula for “Floating Toward Ecstasy” (Jan/Feb 2017). For more, visit macduffeverton.com.

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Enjoyed the story and this fellow is a Saint.