Summer is for steamy romance. Our new series of classic fiction from the 1940s and ’50s features sexy intrigue from the archives for all of your beach reading needs. In “Petticoat Empire,” an advertising producer is over budget and under staffed, and she’s falling for a know-it-all writer. This 1951 short story offers a glimpse into the glamorous atmosphere of midcentury advertising, romantic cajoling and all.

Little Gem Advertising Film Productions had one rebuilt 35-millimeter camera and a 30-by-50 portion of warehouse space called the studio. Little Gem also had two motion-picture directors who doubled as cameramen, and a producer. The producer was a brunette with bright brown eyes, and her name was Nathalie Wyman.

Nathalie was no secondhand rebuilt. She was young and beautiful. What you could see of Nathalie was gorgeous and what you couldn’t was provocatively covered by Hattie, Nettie and Sophie.

Men made passes at Nathalie which she promptly passed by. Her master plan for traveling the road to success permitted no dalliance along seductive bypaths. Men were things to think about later after she had been called to Hollywood to produce extravaganzas in color. She expected, of course, when she got around to it, to take her pick from a whole herd of rich, dynamic captains of industry.

In the meantime she looked in her office mirrors and told herself she was the best producer in the less glamorous side of motion pictures. Her production meetings went off like clockwork. Her shooting schedules never sagged into overtime. From script to negative to customer — one Little Gem production — all under budget.

Nathalie’s pet customer was Babyskin Lotion, and so the 10 o’clock production meeting for Babyskin Theater Ad 27, with Nathalie Wyman presiding, should have gone off in the usual routine fashion.

Director Al Kolski sat midway of the desk and read the script aloud. Carol Lee, secretary to Nathalie and plain stenographer to the rest of the staff, hung her pencil in the air and waited for Nathalie’s comments. Doug Wilson, promoted to head writer since the hiring of an assistant, blinked and chain smoked.

His new assistant, Joe Frane, sat with his chair tipped back against the wall. Joe’s eyes were closed. His complete disregard for the presence of the producer was a sizzling fuse under his tilted chair. The fuse was attached.

Her annoyance mounting by the minute, Nathalie stared holes in the wall over Joe Frane’s head. Insolent boor. What was it Wilson had told her about him? Newspaper reporter who’d worked on films in the Navy. Single, in his late twenties. Writers! Every day, litters of them could be crammed into weighted sacks and dropped in the river and no one would ever ask what happened.

A strange word jerked her thoughts into line. Uxorious. What did that mean? Ferd Zwinnick, sales-promotion manager for Babyskin, wouldn’t understand it. He’d say, “If I don’t understand it, the audience won’t either.”

Kolski finished reading and passed the script to Nathalie. Joe’s chair came down with a thud.

“Damn good,” Joe said, sliding to his spine. “Thought I’d gone stale on it, but it’s better than I guessed.”

Wilson darted his assistant an invisible ray designed to wither, but Joe, lost in admiration of his opus, remained healthfully ignorant. Kolski reverently turned his face to Mecca, and Wilson followed suit.

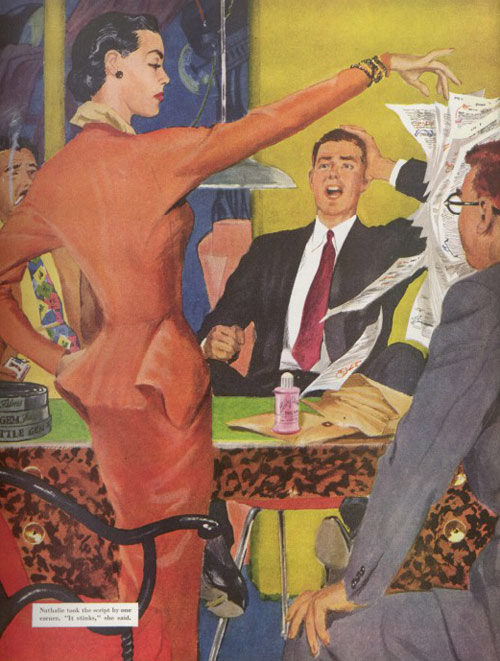

Nathalie took the script by one corner, holding it away from her, shoulder high, like something lifted from a sewer. She wheeled from her chair and tossed it toward the wastebasket. In a coldly regal voice she exploded her bomb, “It stinks.”

Joe hit the floor. Six feet of him seemed to lean over the table all at once. Nathalie braced herself for a bellow, but what she heard was as quiet and smooth as steel drawn over velvet. He had the bluest eyes she had ever seen. “In just what spots would you say the odor is offensive?”

“I don’t have to be specific, Mr. — ah — Frame.” There was a definite accent on the “I.”

“Frane. But call me Joe; it’s chummier.”

Nathalie ignored the offer. “I want another script immediately, Wilson. We’ll have to switch schedules, shoot Daisy Food Choppers tomorrow and put Babyskin over to the day after. Mr. Zwinnick is arriving sometime today, but I’ll have to stall him off. And, Wilson, you’d better do the rewrite yourself, so the formula will be followed.”

“Formula!” Joe’s voice bled with anguish. “That’s the trouble with your Babyskin ads. I ran the whole 26 yesterday, and every one is five minutes of commercial blah. People don’t talk that way. Not real people.”

Nathalie knew the signs. In another minute he’d reach the shouting point. Deftly she applied the needle. “At Little Gem we give our customers what they want. That’s Lesson One, Mr. Frane.”

“Even if they want castor oil straight, I suppose. Look, Nat. Did you ever try giving Zwinnick some orange juice along with it?”

“I am not paid to waste my time arguing with writers!” Her face was getting hot. “If you can’t understand an advertising formula, you don’t belong in the business. The script is no good. Wilson knows it. So does Kolski.”

As one man, Wilson and Kolski nodded agreement.

Joe looked at them all in turn. Then he smiled and bowed from the waist.

“Thanks, Miss Wyman,” he purred. “Thanks for the unbiased hearing. Even as a puppet show it wasn’t worth the price of admission.”

He went out. Nathalie stomped to a window and stood there, her back to the room. The others slowly pushed their chairs aside and stole away.

She sat down at her desk and put her face in her hands. She had lost her temper, and so she had lost the battle. A new script would be written, yes, but he’d made her look petty and ridiculous with that easy way of his. He’d drawn her in and then he’d slapped her down with a bow and a Cheesy-cat grin. Puppets! Naturally, out of courtesy, Wilson and Kolski always waited for her opinion.

She got up and looked in the mirror between the windows. Not a curl was out of place. She consulted the full-length mirror on the powder room door. She pulled down her girdle and straightened the topaz clip on her lapel. No one at Little Gem had ever called her “Nat.” “Look, Nat.” There was an earnest warmth in the way he’d said it. Sort of made you glow inside, even if it didn’t mean anything personal. Maybe he would quit. Well, so what? The script wasn’t any good. But if Wilson made a fuss she’d better be sure of her facts.

She pulled the script from the basket and returned to her desk. She read it over, word for word, and reluctantly conceded she had missed a few things while working herself into a state over Frane’s lackadaisical attitude. Too many scenes, though. He must have thought Zwinnick was made of money.

Look, Nat. Go on and patch it up. The guy knows how to write. Tell him why you can’t produce it. Tell him the truth.

She put on new lips and went upstairs, where she never went. Her own office was draped and carpeted, and people came to her. She never went to anyone as she was going now to Joe Frane.

The staff room was a barren waste without benefit of partitions. A few battered desks were pushed into various positions to catch the light. Carol’s was in the middle, and there she sat, pounding her typewriter and answering telephones. Wilson was out, and Nathalie wondered if he was already on the prowl for a new assistant. The farthest desk held the lower extremities of Joe Frane. He was on his spine again, his hands clasped behind his head.

She found a kitchen chair and dragged it bumpety-bump across the floor. Joe heard the alarm and unfolded.

She sat on the edge of the chair and handed him the script. “I read this over after you left and It’s all right — it’s pretty good, in fact, but I — that is, we — ” She lost herself in the blue intentness of his eyes.

“But you can’t produce it,” he finished. “Seems to me I heard that before.”

“You’re not to take personally anything that was said downstairs. We give our opinions, but they’re impersonal, you understand.” His hair was brown. He might have been a towhead when he was a kid. He had big-knuckled, outdoor hands — not white, womanish hands as so many writers had.

“Impersonal,” he said. “I see.”

“It keeps us from getting our personalities mixed up with our work. I thought if I explained our policy, you wouldn’t do anything hasty. I mean — ”

“That topaz clip you’re wearing.”

Her hand went to the clip. “I was going to say that by keeping everything impersonal we — ”

“It matches your eyes. Is it Brazilian?”

“I don’t know. I bought it at an auction. Is that good — Brazilian?”

“Very good. Citrine quartz doesn’t have that lively depth of color.”

She was silent before this vast display of knowledge. If he knew stones, there was no telling what other fascinating things were stored away in his mind.

He said, “Let’s forget the formula business. What’s the real reason?”

“The formula is not acceptable,” she snapped. Darn him anyway.

“It wouldn’t be budget, would it?”

He had drawn her in again. Budget was the truth, the truth she had come to tell him, only he’d got her off on a detour by way of Brazil. She slapped the desk. “Yes, if you want to know! I’ve never gone over budget on any picture yet, and I don’t intend to. We can bill 500 dollars for Ad 27, and that’s all. Your version would double that amount.”

“Babyskin spends a million a year on advertising. If you ask me, somebody’s selling you short.”

“I’m not asking you! I’m very happy Mr. Zwinnick favors us at all.”

“Five hundred peanuts. And I thought this business was going to be fun.”

A phone rang. Carol answered it and covered the mouthpiece with her hand. “Miss Wyman, Mr. Zwinnick is here, and he’s down on the stage. He’s getting in everybody’s hair and they want to know what to do with him.”

Nathalie looked from Carol to Joe and her eyes sparked with inspiration. Pulling Zwinnick away from his beloved playthings was a man-sized job. Zwinnick wouldn’t stand for any trumped-up nonsense.

She said, her voice dripping honey, “Mr. Frane, get Mr. Zwinnick out of the studio and into my office, will you?”

Joe ambled toward the door. “You want him vertical or horizontal?”

“Vertical, if you please. Little Gem doesn’t insult its customers.”

Smiling as she had not smiled that morning, she stopped to dictate a memo to Carol. When she returned to her office, Zwinnick was sitting beside her desk, rosy and cherubic and meek as a lamb. Joe was nowhere to be seen.

She had dinner with Zwinnick at his favorite bar. Zwinnick talked. He liked to talk and Nathalie played a customer’s game. While he post-mortemed the speech he had made to the Flat Rock Sales Supervisors Club during the previous week, she nodded at appropriate intervals.

She hadn’t seen Joe all afternoon. Maybe he’d gone home to work on another script. Maybe he’d quit. Or been hit by a car while crossing a street. He might even now be lying in the police hospital, writhing in agony….

There he was, striding into the bar! And he was all in one long piece. He waved to a couple of fellows and went over to stand between them. One of the fellows was Art Matthews, owner of Artcraft Film. Was Art offering him a job?

She tried some frantic telepathy. Don’t take it, Joe. Don’t listen to him. Loyalty to Little Gem is our first principle. Or loyalty to the customer . . . or something. I’m your conscience, Joe. Turn around, so you’ll know I’m here.

But the air waves were clogged with static and Zwinnick. Joe finished his drink, gave Art a friendly pat and disappeared.

Zwinnick ordered dessert — chocolate ice cream roll laced with marshmallow.

“And before I give that speech again,” he said, “I might even improve it a little. Last night I had a stomachache and couldn’t sleep, so I got to thinking. Listen to this, Nathalie. ‘Salesmen are made, not born.’ How’s that for a punch title?”

“Wonderful,” Nathalie said. “I think it’s just wonderful.”

She went home early, begging off from the movie he wanted to see. He would talk all through the picture. And later, over midnight coffee, he would tell her again that a widower’s life was a mighty lonely one.

She paced her apartment. She looked up “uxorious” in the dictionary and wished she hadn’t. She took a shower, shined her hair with a hundred strokes and got into bed. She tossed and turned and punched her pillow into assorted lumps. She was in love. It wasn’t romantic. It wasn’t even mutual. She didn’t want a writer and she didn’t want to live on a writer’s salary. She wanted her career, her annual bonus, and Hollywood and a captain of industry. And she wanted Joe Frane. She felt as if she’d been hit by a dump truck.

With a day to kill before Ad 27 got underway, Ferd Zwinnick tried to murder it for everyone but himself. He planted a chair in front of the Daisy Food Chopper set and ordered a light standard moved back six inches. Kolski, getting ready to move it forward, sweated and wiped his face. He ordered the standard moved back, and when Zwinnick bent over to pick some lint off his trousers, he signaled to have it moved forward a couple of feet.

Zwinnick looked up and said, “That’s better.”

“Patsy ready?” Kolski asked.

Patsy entered the set in a calico house coat.

“Quiet, everybody,” Kolski said. “Voice recording.”

The silence bell sounded. The camera ground. Patsy plugged in her Daisy and began feeding it scraps of raw meat from a platter. She hummed a tune and looked starry-eyed as hamburger rolled into a bowl.

Zwinnick sneezed.

“Cut!” Kolski bawled. He put his hands on his hips and glared at Zwinnick.

“Sorry,” Zwinnick said. “I must have caught a cold last night.”

Kolski beckoned his chore boy. “Get that guy Frane,” he muttered. “He pulled that big baboon out of here yesterday, and he better do it now. I got to swallow him tomorrow, but today I’m going to have a holiday.”

Nathalie walked onto the set, a script in her hand. She looked at Patsy, did a double take and marched over to Kolski.

“Where’s Rita?” she asked. “I thought we agreed on Rita.”

“Been hitting the gin and couldn’t make it.”

“The approved script calls for the motherly type.”

“I know, but we decided to knock it out and make it a bride.”

Nathalie stamped her foot. Who did they think they were, assuming the producer’s prerogatives? More than once she had canceled shooting on less provocation.

“Cancel the schedule,” she ordered. “Get Wilson and come into my office.”

Joe Frane went by. Kolski said, “Hi, Joe. Good girl you got, that Patsy.”

Nathalie followed Joe with doelike eyes. He hadn’t quit. He was right on the job.

Kolski’s words broke through her adoration. She whirled angrily. “Joe got this girl Patsy? Where?”

“I don’t know, but she’s something, isn’t she?”

Something was right. She was the cutest model who had walked into the Little Gem studio in months . . . and Joe Frane had got her! His girlfriend, of course. His heavy date. Who else would be so accommodating in an emergency?

“Joe!” she called. She’d have to be smooth about this. Not lose her temper again. Keep it impersonal while letting him know he couldn’t play fast and loose with a customer’s script.

Joe came over.

She said carefully, “Did you see the script? The Daisy people want a matron.”

“This will be better,” Joe said. “Patsy was a food demonstrator and she can really cook.”

Thoughts hammered each other around the ring of her mind: Cancel the schedule. You’re the producer. Get it right. But Joe says. And Joe knows. She said softly, “You think it will be all right, then?”

Kolski, bug-eyed, grabbed the cameraman and hung on. History was being made at Little Gem.

“It’ll be swell,” Joe said. “I’ll guarantee the results.”

“All right. . . . You can go ahead, Kolski. And, Joe — ” She maneuvered him into a neutral corner. “Wilson just gave me his rewrite. It isn’t as good as your original.”

Joe raised his eyebrows.

“I’d like to produce yours if Mr. Zwinnick can be sold on a budget increase. What do you say the three of us have dinner tonight and talk it over?”

“Tonight’s a little late. If he agrees, we’ve still got to round up a cast for tomorrow.”

“I haven’t a spare minute today,” she fibbed. “We’ll make it dinner at my place. Get a tentative cast and tell them we’ll let them know.”

She returned to her office on wings of surging hope. His Patsy girl wasn’t the only one who could cook. Food was important in a man’s life, but even more important was a story to its author.

Her production meeting on Menu 1 for Joe Frane took most of the afternoon. She wrote, edited and rewrote without regard to budget. She left the office early to pick up the items and don a dimity apron.

Her guests arrived at seven. Zwinnick, previously unsuccessful at getting his foot in the door, was charmed with the apartment. Joe was noncommittal, although he appeared lazily comfortable in the lounge chair that fitted his long frame without coaxing. Mentally Nathalie put on his slippers and asked him if he’d had a hard day at the office.

Her program called for no shop talk until after coffee. Then they would read and discuss the script, Zwinnick would grow mellow over the brandy and walnuts, and she would lay the money problem, oh so tactfully, in his well-upholstered lap.

Everything was proceeding famously and … zingo! During the few moments it took her to remove the dinner plates and bring in the salad, her program was kicked out the window. Zwinnick announced he had read the script and the production price was too high.

“Let’s talk about it later,” she said, but no one paid any attention.

Joe pushed his salad aside and got busy with a pencil and notebook. “Since you feel one thousand’s too much, look at it this way, Mr. Zwinnick. We’re featuring all your products that the housewife uses in her daily routine. Wall cleaner, beauty soap and kitchen soap have about 40 percent of the footage. Lotion has 60 percent. Divide a thousand that way and you come out six hundred dollars for Babyskin.”

“Yes, but our other divisions have no appropriations for theater ads.”

“Their television movies are theater ads. It’s only the medium that’s different.”

Joe bored in. He tossed off television costs and theater advertising costs like an automatic calculator. He wrapped up a television-theatrical package and presented it over his untouched salad.

“Still too much money,” Zwinnick said.

Nathalie was crushed. Why hadn’t Joe let her handle it in her own way? Perhaps it wasn’t too late even now.

She stretched her hand across the table. “Mr. Zwinnick,” she said. “Ferd.”

Smiling his surprise, Zwinnick took her hand.

“This picture could make you the biggest man in sales-promotion advertising. You’ve always been a leader, but with a brand-new idea like this you’d be the absolute top.”

Out of the corner of her eye she saw Joe’s face. It looked slightly sick.

Zwinnick said, “I know, my dear, but we’ll have to do our regular version this time. I’m going to think it over, though. It has possibilities.”

Joe smiled. He slipped his notebook into his pocket. “That’s good enough for me, Mr. Zwinnick.”

Men! Folding up and calling it quits before each and every expedient had been tried. She said pleadingly, “We want to do this one picture so very much. It will be a big feather in Joe’s cap, and I want it too. It’s real theater and I’ve never had a chance to do anything like it before.”

Zwinnick gave her hand a quick squeeze. “Let’s do it, then! Anything you want, Nathalie, even if it takes money out of my own pocket! Sure, let’s do it!”

Nathalie turned triumphantly to Joe. What she saw was a frozen corpse, its eyes glassy, its jaws clamped in a mighty disapproval.

The telephone rang and she answered it. “For you, Mr. Zwinnick.”

Zwinnick got up and went into the living room. He said loudly, “Zwinnick speaking. . . . Who? . . . J.B.? Where are you? . . . Oh, I get it. Over.” It went on and on. It didn’t make sense.

She cleared the table and stacked the plates on the kitchen drain board. She heard a step behind her and felt an iron grip bearing down on her shoulders, spinning her around. She looked up into the flashing blue anger of Joe Frane’s eyes.

“Bar none,” he said, “that was the cheapest trick I ever saw pulled anywhere.”

She patted his lapel. “I got it for you, didn’t I?”

Joe backed away and her hand patted air. “The guy was sold! He doesn’t have the authority or the money to do it now, but he’d have done it next time sure as shootin’. This isn’t one picture; it’s 20 or 30. And what the hell do I care about a feather in my bat? Looks like it’s you who wants feathers, and at the risk of overselling your best customer!” His arm swept the kitchen. “Why don’t you just stick to steak and salad?”

Her chin went up. “What do you know about salad? You didn’t eat any.”

“Oh, for the love of Pete! I don’t think you’ve got the point yet.”

The swinging door made a fanning wake behind him.

Numbly she went through the motions of placing coffee and dessert on a tray and carrying it to the table. The dining room was empty. She peered anxiously into the living room, brushed past Zwinnick and ran into the hall. Joe’s hat and coat were gone. She returned to the table and slumped into her chair.

Zwinnick came back, puffing with importance. “That was J.B. Conners, chairman of the board. Talking from an airplane. He may drop around tomorrow. Airplane. Imagine that!” He gulped his coffee. “Where’s Joe?”

“Working tonight,” she replied with her eyes on her plate.

“Nathalie, dear, this soufflé is out of this world.”

In another minute he would tell her, a little more tenderly this time, about the widower’s lot. And in half a minute, to keep him off the subject, she would have to suggest they catch a late movie. Which she did.

Olga Olson, professional model recently returned from a weekend in Louisville, studied the dirty wall and stepladder on the Babyskin set and trembled under her mink-dyed wombat. “Ah thought this was a beauty picksha. Ah’m awf’ly sorry, Mistah Kolski, but Ah just couldn’t wash a wall.”

Joe brought the news of Olga’s departure to the front office, where Nathalie was dictating to Carol. Nathalie listened in frigid silence. This was the man who’d walked out on her. Not once, but twice.

When he finished, she said crisply, “Get your girl Patsy. Let her do it.”

“She can’t. She’s busy this morning.”

Carol said, “I hit the bottom when I called Olga.”

“It’s not my problem,” Nathalie said. “Go worry somewhere else.”

Joe shrugged. “Conners and Zwinnick are sitting on the stage. Kolski’s pulling his hair out and the picture’s got to be in the can tonight. It’s your baby, but it’s not your problem. Okay.” He started for the door.

“Wait a minute,” Nathalie said. “Think hard. Someone who can do housework and look like Hedy Lamarr.”

“You,” Joe said.

Nathalie rose to her full height. “I am not a model. I am a producer.”

“You’d be wonderful, Miss Wyman,” Carol said.

Impatiently Nathalie turned away from them both. She caught herself in the mirror and adjusted an earring. Then she saw something else. She saw Joe looking at Carol. His whole expression had changed. He wasn’t shrugging or not giving a hoot. His face was bleak with worry and his eyes were as tired as an old, old man’s. Joe Frane, so easy and confident, was scared to death! Her heart stopped and went into reverse. This was serious. This was where you got in and pitched. Love and a man who kept walking out had nothing to do with it.

She turned around, murmuring half to herself, “. . . never acted in my life, but at least I’d be no worse than Olga. If I thought I wouldn’t ham it up — ”

Joe snapped to attention with a broad grin. “Now you’re logging! I’ll send in the duds and makeup!”

Ten minutes later she crossed the stage in blue jeans and an old shirt with rolled-up sleeves. Zwinnick put his arm around her and told Conners she was a little gem; ha ha, wasn’t anything Nathalie couldn’t do.

She mounted the stepladder, and the chore boy hoisted two pails of water to the ladder platform. He placed the can of cleaner on the top step. When Kolski shouted “Camera! “she put a spoonful of cleaner into one of the pails and began washing the dirty wall.

She washed. She washed again. And again. The result was a tired arm and a faint light streak that refused to get lighter.

“Cut,” Kolski said in disgust.

Joe called out, “Take it once more. Rub harder.”

She said bitingly, “You can spray the dark part darker, you know. Or don’t you condescend to the tricks of your trade?”

“Anyone can trick a result,” Joe replied. “We want to show the cleaner in action.”

“That’s right,” Zwinnick nodded.

She hated Joe. She hated Zwinnick and Conners. Slave drivers. Flesh peddlers.

“So take it again,” Joe said, “and use some elbow grease.”

She took it four times, and four times Joe shook his head.

Finally he said, “Move the ladder to another place and try it again.”

The ladder was moved. Turning her back to the coaching staff, she emptied the rest of the cleaner into the pail. Then, with the camera grinding again, she gave the wall a vicious swipe, another, and another. Her hands burned with a crimson heat. Her arms weighed a dead ton. She rinsed the sponge in clear water and wiped the space clean. The wall was free from dirt . . . and paint too.

“Cut,” Kolski said briskly. “Next setup.”

She got down and collapsed into a chair. Someone threw her a house dress of a hideous pattern and she staggered into her office to change.

She came back to wash and dry a stack of dishes. She did the dishes five times, smiling. She scoured a sink eight times, still smiling. She got down on her knees to pray for deliverance and smilingly scrub a floor. Each time she finished she was certain it was right, and each time Joe said, “Once more,” and she hated him all over again.

“If you say ‘Once more’ once more, I’ll scream!” she screamed.

Joe caught the scrub brush aimed at his head. “Get it out of your system and take it again,” he said patiently.

She was only dimly aware, two hours later, of the scene ending and Joe lifting her to her feet.

“Shampoo scene,” he said, shaking her into consciousness.

“Not me. I’m starving.” A nice lunch with Zwinnick and Conners would be good for customer relations. It would help her forget the indignities heaped upon her by Simon Legree Frane.

“Shampoo scene,” Joe repeated. “Do it right and we’ll knock off for lunch.”

She did it right . . . or else Joe was going blind. She put in two pin curls and giggled into the mirror above the washbowl. Now she was getting silly.

A hairdresser finished the curls and put her under a drier in her office. A few minutes later Carol appeared with a sandwich and a bottle of milk.

“Mr. Frane sent these,” she said.

“You may tell him for me,” Nathalie returned, “that I always lunch with our customers.”

“Oh, they’ve gone. Mr. Frane took them somewhere in a cab. He had me call Patsy to do the hand modeling. He said your hands weren’t — well.”

Weren’t what? Nathalie looked at her hands. Red. Swollen. Peeling like two scalded tomatoes. “Give me that sandwich and the hand oil,” she said savagely, “and latch the door when you go out. I’m in conference.”

It wasn’t enough that he had kidnaped the customers for lunch. He had crowned his perfidy by calling in someone else to do the easy parts. He could have shot the hand scenes first, before she’d got mixed up with scrub buckets and dish pans. But no. Oh, no! He’d been saving the plums for Patsy all along.

Under the hot breath of the drier, the sandwich tasted like cardboard. She chewed herself into a long, revengeful burn.

They called her at half past three and she walked out to the set with mayhem in her heart. Patsy had gone, but her memory lingered on. Everyone, including Freshman Conners, was fiendish with ill-concealed delight.

Kolski said, “Patsy wrapped that up in a hurry. What a girl!”

“Swell, wasn’t it?” Joe said. “One more shot and it’s in the can. Bedroom setup.” He glanced at Nathalie and the anemic young man with the cleft chin who was to play the uxorious husband. “You two got your lines?”

They delivered, walking through their parts. Joe nodded approval, and shooting began.

Near the end of a good performance she coughed and spoiled the take. Joe inquired if she needed a throat spray, and she replied sweetly that her throat was all right and she was terribly sorry.

They took it again, and she hammed it to the skies, twisting her hips and making baby talk into the camera. It was so bad that Kolski didn’t even comment.

Nathalie leaned against the frame of the bedroom door and gloated. Joe got up and came over. He was looking worried — the way he’d looked that morning.

“What’s the matter?” he asked.

“Not a thing,” she said innocently. “I thought it was fine.”

They took it again. She kept her hips at home, but she topped the young man’s lines. The result was a conversational rat race. It was beautiful.

Joe paid her another visit. “If I didn’t know you were a trooper, I’d swear you were deliberately cue-biting. Your timing’s all wrong. Look, Nat. When he says, ‘Hi, dear,’ count three before you answer, and when he — ”

She didn’t hear the rest. “Look, Nat.” Those words again. Those wonderful, wonderful words. Birds were singing madrigals inside her head and gaily colored flowers were springing up to cover the scars on her heart.

“I’ll go through it with you,” he said, “so you’ll get what I’m driving at.”

“Joe!” Zwinnick called. “Wait a minute. I’ve been thinking. The husband brings in the two presents, but he opens one, the bottle of Babyskin. The camera dollies to the bottle, the husband talks about it and we go on from there.”

“The idea,” Joe countered smoothly, “is to bring in the Babyskin as a climax. It’s more subtle, Mr. Zwinnick.”

Nathalie folded her arms and waited. Joe was right. No he-man would plop a bottle of anything — nectar, wine or Babyskin — into the middle of a scene of connubial bliss and make like a radio announcer.

Zwinnick shot his finger at Joe. “I’m not interested in climaxes. It’s advertising I’m after. The scene will play better my way.”

Joe said, “Then what do you say we shoot it both ways? You can see both versions and decide which you like best.”

Hurray for Joe, Nathalie thought. Spoken like a gentleman and a salesman.

Zwinnick turned red. His neck swelled. “We’ll take the one version, and we’ll take it the way I want it!”

“We will not!” Nathalie crossed the stage in three strides. “You listen to me, Ferd Zwinnick. That scene will be shot the way Joe wrote it or it won’t be shot! You approved that script, so keep quiet and let us get on with it! If this job runs into overtime, you’ll get a bill that will knock your hat off!”

She found Joe beside her, and she put her hand on his arm to steady herself. Anger was fast giving way to sheer fright.

“Do we shoot it or don’t we?” she demanded.

Zwinnick looked grim. Then, unaccountably, Conners threw back his head and brayed loudly. Laughing and choking, he said, “I guess we shoot it, Ferd.”

Zwinnick’s face puckered into a grudging smile. “Yes, J.B. Yes, sir. I guess we do.”

“Now, Joe,” Nathalie said, “if you’ll show me the way you want it — ”

“Good girl,” Joe whispered. “I’ll be right with you.” He went into a huddle with Kolski while Nathalie took her station behind the bedroom door. She heard him coming into the hall.

“Hi, dear!” he called.

She counted three and opened the door. “Darling, you’re home early. I’ve been so busy all day I’m not quite ready for the party.” Spying the two packages: “Oh-h, presents!”

“What do I get?” he asked.

“This.” She came into the hall and kissed him, her arms going around his neck. His hold tightened and he returned her kiss with astonishing fervor.

That second kiss. It wasn’t in the script. But good. Uxorious. This was really rehearsing!

He handed her the larger package. “Put it on, will you? I want to see you in it . . . right now.”

She disappeared into the bedroom to make a quick change. She opened the door and stood before him in a pleated chiffon negligée. He whistled as he walked into the bedroom, followed by the camera.

“And the other package?” she said coyly.

“The best I could get.”

She unwrapped a bottle of Babyskin and flew into his arms. She must remember not to say “uxorious.” Zwinnick had changed it. “Babyskin! Oh, darling, just what I wanted. You’re the most . . . loving husband a girl ever had.”

“Babyskin, h’m’m’m.” He rubbed his cheek against hers. “Babyskin is right.”

He kissed her again, and this time her lips were not surprised. They were waiting, eager. She leaned against him and sighed ecstatically. The camera came in to a close-up of the bottle she clutched behind his back. Rehearsal was over.

“Swell,” he said, still holding on. “And all so darned impersonal.”

“Wonderful,” she said. “Or would you rather rehearse with Patsy?”

“What’s she got to do with it? She’s my sister-in-law. With three kids, she can’t always get a sitter.” He squeezed her hard. “She couldn’t take it the way you’ve taken it today, believe me.”

A light went out. A wall of the bedroom started walking away. Dazed, she looked around.

“They’re striking the set! Tell them to wait. I’ve got to do it with that tailor’s dummy.”

He smiled. “It’s a take. He gets the money, but I get the gravy. After the way you handled Zwinnick, I knew you’d be great.”

“I’ll bet I’m canned,” she whispered, not caring at all.

“Conners loves it. I corralled them for lunch, so I could get his blank check on the deal. He told Zwinnick he wouldn’t allow him to spend a cent of his own money. You weren’t sore, were you?”

“What a silly notion! As if I could be . . . with you.”

“Get your clothes on and let’s get out of here. I need a steak.”

She backed away from his unmistakable meaning. “Oh, no, you don’t! I’ve had a hard day. I’ve scrubbed and slaved, and I’m not cooking any steaks tonight.”

“Tomorrow night . . . if you haven’t any other plans?”

She wanted to run to her mirror, to tell herself there were no other plans, not now. But she didn’t move. The only mirror she needed was in his eyes.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a well written story we have here in ‘Petticoat Empire’, offering a fascinating behind-the-scenes look into the advertising world at the dawn of the television age.

A female producer who looks like Hedy Lamarr, yet can be the all-American housewife for the camera in a pinch to save the day, and the budget. A dame that knows how to work with the guys trying to knock her down, yet work them to her advantage in the end.

The dialogue here is state-of-the-art for the time, and an ever bigger treat to read in the present day. What do we take away from the story? That the right “man” for the job is a woman.