Flickering with candlelight on brick and stone, the basement of a seemingly ancient church in Buffalo evoked a catacomb — yet with a bar gleaming and a hipster presiding, it felt very much of its moment, too. The creative-reuse site was called Babeville, a former church turned into an unexpected concert venue (with backing from the music star Ani DiFranco, a Buffalo native). Bernice Radle, barely 30 and stylish in her long hair and thick-framed glasses, was convening a happy hour for Buffalo’s Young Preservationists — and their more senior counterparts — not long ago.

She waved around the space, describing how the building had been headed for demolition until preservationists banded together. Retired academics and longtime activists half-circled her in a mix of support and fascination, as if a black-necked swan had glided in among them. Radle named the passions driving her generation to retain and reuse Buffalo’s turn-of-the-century urban core. “People love to complain about millennials, but we love community, and we love old things, and we love bringing people together,” she said. “We’ve had friends literally getting tattoos on their body to help save old buildings.”

In Rochester, another upstate New York city hollowed out post-industrialism, Caitlin Meives stepped onto a parklet’s picnic bench on a mild August Saturday and outlined a race. Rochester’s Young Urban Preservationists, or YUPs, were putting on their signature annual event of the past few years, a bike scavenger hunt. The 60 spandexed participants would pedal eight miles around Rochester’s historic streetcar suburbs, stopping at sites like the railbed where the Rochester and Sodus Bay Railroad, a commuter steam line, had once run through. Meives, 34, stood up to get the riders’ attention, a neon bandana tied Rosie the Riveter-style around her top-knotted hair.

Did everyone have the list of clues? Any questions? “Beer!” someone shouted. Afterward, Meives promised. The racers would pull back up outside Joe Bean, a former World War I ordnance factory recently reimagined into a sleek coffee shop, kitchen, and bar, and drink local brews together at the picnic tables. The participants were there to raise public awareness — and their own appreciation — for the historic infrastructure of this Rust Belt city. But they were going to do it in distinct 21st-century style, drawing on millennial-generation favorites like bikes, pocket parks, and of course, craft beer.

The Buffalo and Rochester groups that Radle and Meives each cofounded are part of the Rust Belt Coalition of Young Preservationists, a regional nerve center of the new movement to preserve old American infrastructure. Leading the movement is an emerging generation of history lovers in their 20s and early 30s. Besides bikes and beer, they’re creatively using more new tools — including unexpected humor, star power, social media, and yes, even the occasional well-placed tattoo — in order to save old buildings and revitalize their cities.

These new preservationists are loosely organized, often not even establishing themselves as nonprofits, applying for grants, or carrying insurance. They’re less apt to do neighborhood organizing, fight acrimonious newspaper battles, and sue to block demolitions than their predecessors of the ’70s, ’80s, and onward. The younger set believes they’ll do better by befriending developers than by facing off as their adversaries. How successfully this approach works will determine the long-term retention of American architecture, the structure and millennial appeal of many U.S. cities, and the future of some of the country’s former boomtowns.

At least 40 young-preservationist groups are now at work across the country, according to tracking by the Washington, D.C.-based National Trust for Historic Preservation. Diana Tisue, a 27-year-old project manager there, has become the trust’s direct liaison to the new groups. Tisue got her start founding the U.C. Preservation Action Network while at the University of Cincinnati, and then the Cincinnati Preservation Collective after she graduated in 2014. The citywide group has become known for attention-grabbing moves, like dressing as old buildings and producing a “Torn Down for What?” music video that spoofed a 2013 rap-electronic dance hit. (“For another parking lot?” the video asks as its stars gyrate.)

Tisue has watched groups around the country try similarly imaginative new tricks, which they promote on the photo-sharing app Instagram and other social media. A signature move they all share now is “heart-bombing.” Buffalo’s Bernice Radle came up with the idea to arrive en masse at neglected buildings carrying glittery hearts (and snapping pics). “There’s definitely fresh energy, new tactics, and finding inventive ways of saving old things by doing it on bikes or producing a preservation beer or doing a scavenger hunt,” Tisue says. “Young preservationists are coming up with ways that work for them. To do these DIY activities is sometimes easier and cheaper. Going to big fundraisers is not necessarily their style.”

Next-generation groups have been active from coast to coast and beyond. Philadelphia has a big hive, with 750 attending its events over the past four years. In the Midwest, smaller but dedicated bands in Columbus, Minneapolis, and Omaha have heart-bombed their cities enthusiastically. Even states with relatively newer built environments, such as California, are home to groups like the San Francisco Young Preservationists Network and We Are the Next. Some younger organizations, like in New Orleans, have stepped back a bit, while others, like in Washington State, are just starting out.

The hub of activity, however, is unquestionably in the country’s mideastern section, where the Rust Belt Coalition of Young Preservationists counts chapters in New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. The coalition hosts Rust Belt Takeovers several times a year, descending on a St. Louis or a Detroit like a just-formed fan club. Takeover participants pedal around the chosen city’s abandoned sites, drink coffee and beer in its rehabbed bars, and generally cheer about its cool old features. The most recent Rust Belt Takeover was in Columbus, Ohio, in April 2018, with over 100 participants.

Pittsburgh is among the Rust Belt’s new-preservation strongholds; its Young Preservationists Association formed early, in 2003, and established itself as a nonprofit complete with governing board. Since then the YPA has tried out initiatives like a recent grant-funded preservation podcast series. The Pittsburghers get laughs, too — hitmaking vice-chair Mike Panzitta got the idea a few years ago to write punny “Missed Connections” ads on Craigslist for abandoned buildings. “Our love used to span neighborhoods, but when you shut me down 8 years ago, you tore them apart.” One ad, for an old pedestrian bridge, read, “You used me and you walked all over me. You need to earn my truss back.”

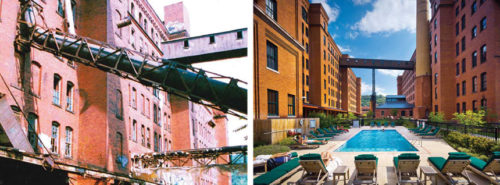

Well-organized, the Pittsburgh group is known locally for putting out an annual list of “Top 10 Preservation Opportunities” (about one-third of the places named over the past 15 years have since been preserved, the YPA estimates). Among the notable saves are Dormont Pool, a beachy neighborhood swimming hole dating to 1920, and the hyper-luxe Cork Factory Lofts in the now-trendy Strip District; now they’re working on that forgotten pedestrian bridge over a rail line in a North Side park. The YPA has also been ahead in assessing economic impact. The group commissioned a study that found that $1.30 in private spending is spurred by every public dollar invested in Pittsburgh.

Perhaps it’s not coincidental, then, that Pittsburgh is furthest along in its comeback — the Rust Belt city most likely to be named one of the country’s hottest urban areas by the likes of Travel + Leisure, TIME, even the National Association of Realtors. When developers want to open in Pittsburgh now, they tend to refurbish old buildings rather than build new; the hip boutique Ace Hotel is in a former YMCA, and the hot new restaurant Superior Motors is in one of the country’s first indoor Chevy dealerships. “People are looking for a place with character,” Panzitta says. “We’re giving people who have the impulse to preserve an outlet to work on that.”

The American mindset has definitively shifted since the days everybody wanted to tear down the old infrastructure of buildings and city streets and build new malls and freeways. Build for the future — transportation by automobile — the all-powerful New York City planner Robert Moses urged, and let the suburbs grow. These days the ideas of Moses’ adversary, Jane Jacobs, are more ascendant. Jacobs’ 500-page treatise, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is studied by young preservationists, who embrace denser and more walkable neighborhoods. The zeitgeist is pro-urbanism these days, and the new preservationists freely acknowledge that it works in their favor, making persuading developers easier than decades ago.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation is taking a more expansive view of what preservation means, getting people beyond the idea of establishing the traditional house museums. Its “This Place Matters” campaign has taken on a year-round life of its own; the #ThisPlaceMatters hashtag has passed the 80,000-use mark on Instagram. People like Tisue coach young people that preservation can mean not only showing up to a city council hearing about a building, but also buying a building yourself, talking to a developer about their plans, or holding a “This Place Matters” sign.

Events like the Rochester bike scavenger hunt help people like Danner Hickman, a 35-year-old real-estate researcher, see themselves as preservationists. “If you’d asked me a couple years ago, I wouldn’t have thought so,” she said over a fruit-infused “beer smash” post-race. “One of the things the YUPs did was talk about a new, more expanded definition of what it means to be a preservationist. When they went through the list I was like, yup, yup, yup, check the boxes.”

The question is whether getting more new people into the tent translates into saving historic structures. Young preservationists have suffered some high-profile losses of some of the buildings they’d championed. In Cincinnati, the younger set rallied around the Dennison Hotel, while traditional preservationists were warier; in the end, despite a nearly two-year battle that did spill into court, the landmark structure was demolished anyway. Reflecting on the effectiveness of enthusiasm versus legal maneuvering, Tisue pauses. “It’s hard to say,” she allows. “Hiring a lawyer isn’t the only way, but sometimes it’s been necessary.”

Even heart-bombing has had mixed results. In 2013, the Buffalo group nailed up some plywood on a historic malting plant and painted a two-story heart that was visible across the Niagara River in Canada. “Buffalove,” it said. The community loved it so much people took engagement photos in front of it, and its image was imposed on popular throw pillows. The city ordered the giant heart taken down anyway. The term took off — locals still profess their “Buffalove” — but the building remains in limbo.

—Ad posted on the “Missed Connections” section of Craigslist for an old pedestrian bridge in Pittsburgh

There are critics of the new approach — and not all on the bulldoze-and-start-new side. Veteran preservationists like Buffalo’s Tim Tielman argue that the younger generation needs to become more hardheaded in its tactics if it wants to save buildings, filing lawsuits rather than crafting hearts. Tielman is executive director of the Campaign for Greater Buffalo History, Architecture, and Culture. Over the past few decades, the nonprofit’s dogged legal action has saved from destruction some of the city’s biggest historic structures and sites, including Ani DiFranco’s Babeville.

Two people with a formal organization, an appetite for neighborhood organizing, and a lawyer can be more effective than 100 people without structure to back them up, Tielman believes. Policymakers look for diverse groups of their own constituents, he says, and quickly tune out social media. “If you are a nonmembership group, a loose coalition, you have no standing when the rubber hits the road,” he says. “You cannot bring a lawsuit. You’re a nonentity before any court. What leverage do you bring to bear? I just haven’t seen the efficacy.”

Radle is frank and unapologetic about those limitations, and she’s willing to save buildings one fixer-upper, one neighborhood, at a time. “We’re not here to try to be formal — then we’d have to deal with board politics. The informality allows us to be flexible and get stuff done,” she says. “We’re so nimble and quick — DIY, cheap, and that’s basically it. We have nothing to lose, literally.”

Lynn Freehill-Maye is a freelance writer whose work has been published by The New Yorker, The New York Times, Travel + Leisure, and Texas Monthly. For more, visit lynnfreehillmaye.com.

This article is featured in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now