Humankind breaks a lot of things in the name of science. We take apart plants to see how they grow. We dissect organisms to see how they work. We crush minerals to examine their composition. And sometimes, we slam subatomic particles together just to see what happens. That’s the extremely simplified mission of the Larger Hadron Collider, which fired up its first test at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, ten years ago.

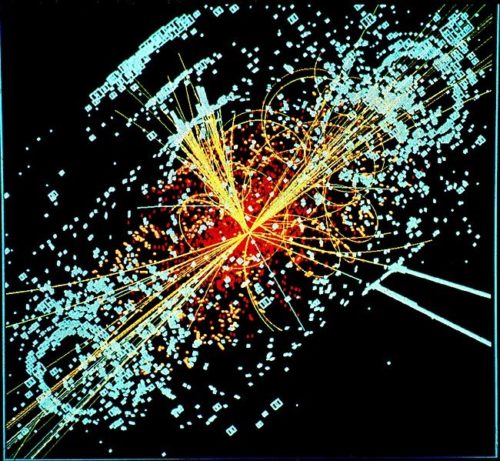

Simply put, the collider allows scientists to make particles smash into one another so that they can study the effects. The collisions allow observers to learn things about natural laws and forces, to address certain questions and theories about space and time, and even probe some of the deeper mysteries of the universe. This is not the playground of the inexperienced amateur.

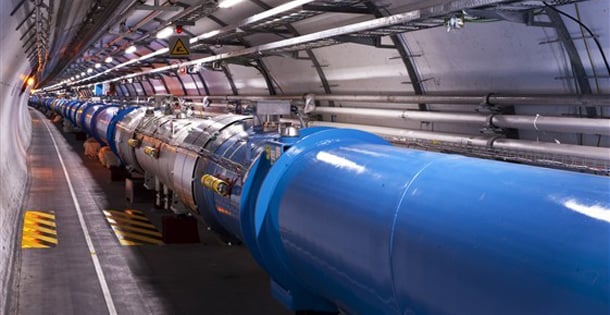

The very existence of the Large Hadron Collider owes itself to a massive effort involving a cast of thousands. Built over the course of ten years between 1998 and 2008, the project required input from over 10,000 scientists from more than 100 countries. It’s the biggest machine on the planet, placed in a tunnel with a 17 mile circumference below the ground at the border of France and Switzerland. It’s actually big enough that the tunnel crosses the border at four separate points. The computer network required to run the whole thing is so massive that it has 170 stations stretched over 42 countries. The overall budget for the project came in at $9 billion.

Even with all the great minds and money involved, the Large Hadron Collider hasn’t been problem-free. The first successful test ran on September 10, 2008, as a beam of protons was fired around the length of the collider. Unfortunately, the LHC had its first major mishap just nine days later when what was most likely a faulty electric connection damaged 53 superconducting magnets in the array. The machine ended up being down until November of 2009, after which it has generally run as expected, briefly pausing to be upgraded in 2013 with a resumption of operations in 2015.

One might wonder why all this cost and effort has been expended on such a device. On one level, it’s about the very idea of discovery. The LHC is part of a process that tries to deliver us an understanding of the basic building blocks and forces of the universe. It helps us understand how matter and energy work. As for practical applications, how would this giant machine benefit mankind? Writing for the BBC, science editor David Shukman probed that question; he pointed out that many scientific discoveries have led to new inventions after the fact, citing how NASA engineering led to the non-stick frying pan and how other work at CERN led to the creation of the internet.

Among the major findings owed to the LHC is the confirmation of the Higgs boson particle. Previously only theoretical, the existence of the particle was confirmed by collision data in March of 2013. It’s also understood to be the particle that gives other particles their mass, so it’s a previously unseen, but fundamental, piece of existence. Discoveries like this help us understand what we’re getting right or wrong about science, energy, and matter and improve the way that we’re studying molecules and the composition of the universe. Further work has revealed the existence of other particles and opened the groundwork for new theories of how the universe might fit together at the smallest levels.

The LHC has been the subject of some wild speculation in both fringe media and pop culture. Some conspiracy theorists believe that the LHC is capable of opening black holes or that it’s very existence may threaten the Earth. Others believe that the universe was fundamentally altered on September 10, 2008, when the machine was fired up and that we’re now living in an alternate branching timeline created by the LHC. As you might expect, there’s no evidence that anything like that occurred. Even a couple of scientists tried to sue to stop the activation of the LHC, but failed to stop it. On the lighter side, CERN and the LHC have been mentioned in novels and film, and CERN has often good-naturedly produced “fact vs. fiction” website updates or print publications to reiterate the safety and non-world-threatening nature of the work done with the LHC.

Even if the science is a little hard for the average person to grasp, the people at CERN and the Large Hadron Collider have definitely broadened the scientific understanding of the universe. As they continue with more experiments and further planned upgrades, there’s no telling what discoveries they might make in the future. One thing is certain; for the past ten years, they’ve done a smashing job.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Such things that can affect the entire planet should be put to a vote by the population of said planet i.e. the human race and should be enforced and overseen by united nations

Before the first test run in 2008, as far as we know, the earth, or our timeline in this universe has not had the power to test such things.

So to say CERN has not changed our reality-fundamentally, is incorrect.

I think we just may not ever know to what extent CERN has changed it.

I agree with the person who commented that it’s amazing to look at the past decade and say “there is nothing wrong” while keeping a straight face! We humans have a VERY long history of obtaining capabilities before we have learned to wield them in a responsible way. The very fact that this article makes mention of scientist slamming subatomic particles together “just to find out what will happen” is the epitome of IRRESPONSIBILITY! you are messing with matter and antimatter without the academic understanding of all of the possible consequences. Playing God should not be delved into lightly, bc in essence you are basically handing a toddler the keypad to nuclear weapons and waiting to see if they will accidentally punch in the right launch codes! Or worse.

The fact that you can look at the past decade and say with such confidence that nothing is wrong with the universe is amusing.

The cost of the LHC (9 billion) is less than that of a plane carrier or of a nuclear submarine. And the benefits between this machine of research, taking together all the environment research, and those war machines are incomparable.

Moreover, if we divide that cost between the participating nations, it becomes like the price of a jet for each. So, all in all the investment is a worthwhile compared with the outcome: knowledge, technology development. brains working at full speed for the best of the causes, conferences, students, job generation, etc etc. So contrary to what some pundits may think, the LHC and its upgrade is a remarkable thing. Furthermore, around this big complex, other superinteresting experiments will be done, like alpha and gbar, just to mention a few.