On Christmas night, men, women, and children come out of the hills and surrounding farms to sing carols, light candles, dream of miracles, and open their hearts to the presence of God.

Mead Schaeffer

December 30, 1944

As dusk begins to move through the snowy woods surrounding the old Vermont church, I carefully guide my car off the road and into the clearing where the building has nestled for almost 200 years.

Originally built by a group of Quaker farmers, the church is simple — a white, two-story clapboard building with tall, many-paned windows that look out toward an ancient cemetery and the surrounding trees.

There are only two rooms. One, a long, narrow space lined with old bookcases and wooden benches, is where visitors are greeted, firewood is stacked, extra song books are stashed, and an ever-changing bulletin board follows the service work of our members around the world.

E.M. Jackson

February 28, 1925

The second room opens off the first. It’s a soaring space of tall windows, white walls, wainscoting, and rows of wooden benches that form a square around a woodstove nearly as old as the church. Kindling is neatly stacked in a woven basket beside the stove, while here and there a colorful afghan is thrown over a bench to warm one of our older members against the inevitable winter chill.

There is no furnace. No telephone. No cell service. No electricity.

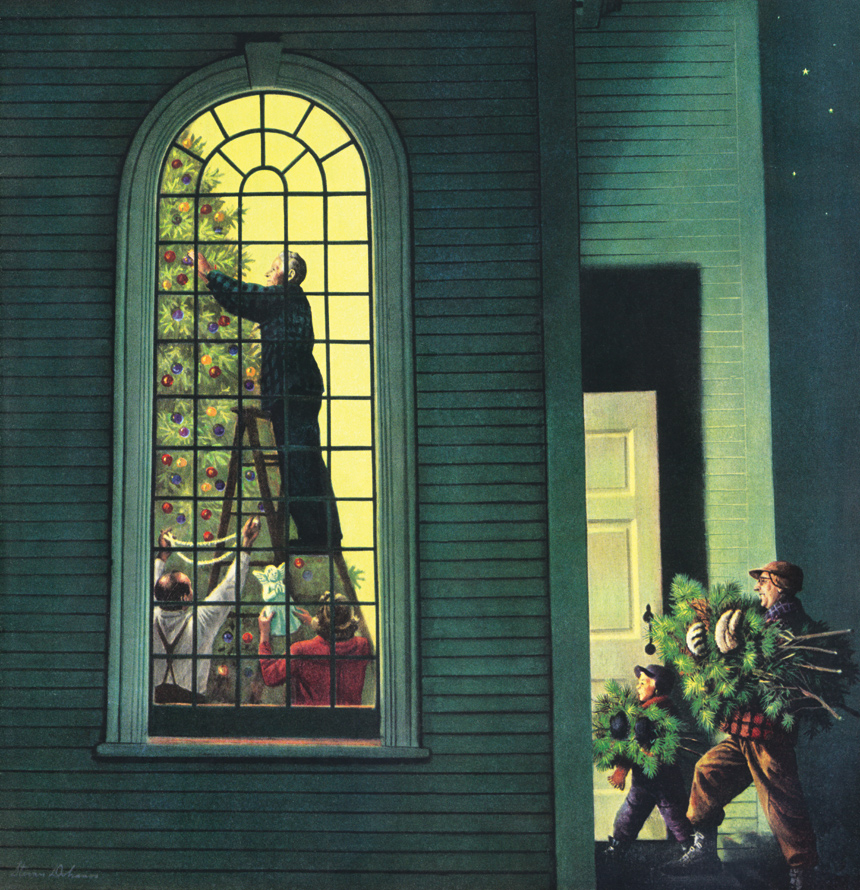

Stevan Dohanos

December 27, 1952

Chuckling at our determined efforts to keep the world with its 24/7 electronics at bay, I open the car door and begin to unpack the miles of balsam and fir that my friend Dave has woven into garlands for our Christmas celebration. I drag them through the snow to the church steps, drop them, then return to the car for candles, pinecones, and loose greens to lay on our windowsills, plus a dozen candles to line the snow-covered path from parking area to sanctuary.

A dozen or so families worship here each Sunday. But on Christmas night, more than a hundred men, women, and children come out of the hills and surrounding farms to fill the benches, sing carols, light candles, dream of miracles, and open their hearts to the presence of God.

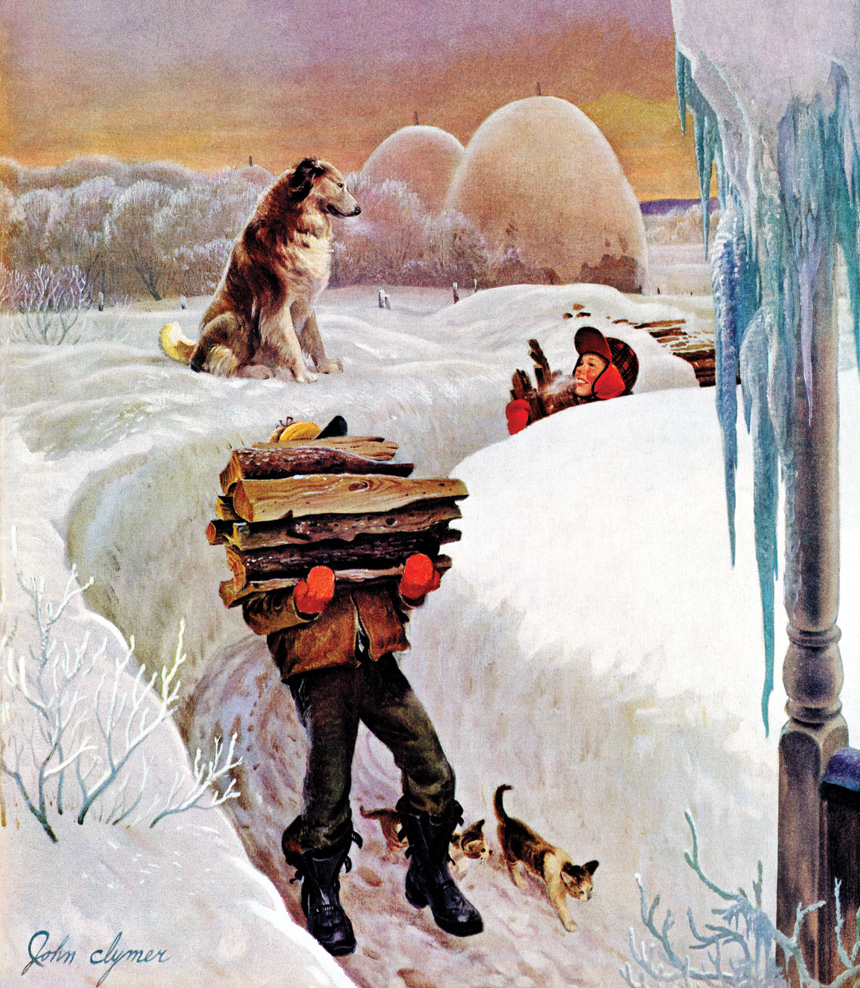

John Clymer

January 27, 1951

There will be the farmer from down in the valley who is trying to make sure there’s a place for family farms in the 21st century. The legislator from a nearby village who wants to build a better community. The teen who left a difficult home and is taking the first tentative steps into a new life. The elderly woman embarked upon her last journey.

Afterward, everyone will gather around the huge Christmas fire in our woodstove to sip hot apple cider, munch on homemade cookies, greet neighbors, smile at strangers, talk about the weather, comment on the price of wood — and experience the strength and love of a faith community.

Joseph Hirsch

December 11, 1948

Hauling the last greens to the church, I plop down on the top step to catch my breath and think about the folks who come to visit.

After the last log has tumbled into fiery sparks and the candles are low, they’ll pull on parkas and mittens and, reluctantly, trudge out into the dark winter night. But before they reach their cars, they’ll each pause and look back at the old church, the path to its door lit by a dozen glowing candles in the snow.

Mead Schaeffer

December 26, 1953

And, in some ancient way, each person will understand that no matter how dark the night, or how difficult the path, the Light found here, at this small church in the mountains, will always overcome the darkness.

Ellen Michaud is an award-winning author whose last piece for the Post was “Living on Less to Give More” in the November/Dececember 2017 issue. For more, visit ellenmichaud.com

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now