Ketchup is arguably the United States’ most ubiquitous condiment. Ninety-seven percent of Americans have a ketchup bottle in the fridge, usually Heinz, and we buy some 10 billion ounces of the red stuff annually — almost three bottles per person per year. We purportedly spend more money on salsa, but in terms of sheer volume, ketchup comes out on top.

Bright red in color, tangy, sweet, salty, and replete with a “meaty,” tomato-ey umami hit, ketchup provides accents of color and flavoring, as well as a smell and texture that is familiar and comforting. It’s the perfect complement to the American diet, contrasting with salty and fatty flavors while enhancing the sweet notes in our most popular foods. And while we think of it as “merely” a condiment on what we’re really eating, it has helped to revolutionize the way food is grown, processed, and regulated.

We slather ketchup on french fries, hamburgers, and hot dogs (though ketchup with this last is, for many, anathema). We pour it on eggs, mac and cheese, breaded and fried clam strips, and chicken fingers. We use it as an ingredient in sauces and casseroles. Back in the 1980s, politicians and activists even debated its questionable status as a vegetable in school lunches, though in later decades ketchup’s distant cousin salsa made the cut, as did tomato sauce on pizza.

Ketchup is an exemplar of New World-style industrialized food, its distinctive sweet-and-tangy flavor borne of the rigors of mass production. Quintessentially American, ketchup is seamlessly standardized and mass-produced — qualities, along with cleanliness and low cost, that Americans have traditionally valued in their food, often at the expense of taste. Shelf stability, in essence, created what we call “American flavor.”

It’s the perfect complement to the American diet, contrasting with salty and fatty flavors while enhancing the sweet notes in our most popular foods.

Ketchup was not invented in the United States. It began as a fermented fish sauce — sans tomatoes — in early China. British sailors bought the sauce, called ke-tsiap or ke-tchup by 17th-century Chinese and Indonesian traders, to provide relief from the dry and mundane hardtack and salt pork they ate aboard ship. Over the next couple of centuries, ketchup spread throughout the British Empire, traveling around the world with the navy. When they returned home to England, sailors and others sought to reproduce ketchup to liven up standard, stodgy meat-and-potato dishes or stewed fish, or to add flavor to gravies and broths. Recipe writers and small manufacturers experimented to re-create the complex flavors of the sauce, substituting nuts, mushrooms, or shallots for the fish. Most cookbooks of the early 19th century included a few recipes for various kinds of ketchup.

But ketchup became truly American once it was wed with the tomato and bottled industrially. While an early ketchup recipe with tomatoes appeared in Britain in 1817, calling for “a gallon of fine, red, and full ripe tomatas [sic],” and also anchovies, shallots, salt, and a variety of spices, it was Americans who really invented tomato ketchup.

The American tomato, with its origins in what is now Mexico and South America, was introduced to Europeans and North Americans by the Spanish conquistadors, and by the 19th century, it had become a ubiquitous garden plant. (Earlier it had been considered unhealthy and even poisonous.) Tomatoes became the base of many a sauce or stew, and before long were bottled as concentrated, fermented ketchups, preserved with vinegar and spices much the same way housewives would make a mushroom ketchup.

But as historian Andrew Smith notes, tomato ketchup became wildly popular, its use spreading rapidly to all regions of the U.S. American meals during the 19th century, much like the British diet of the time, consisted of stews, soups, rough cuts of meat, vegetables and fruits when in season, and bread, bread, and more bread. Tomato ketchup’s flavor and color literally spiced up some rather monotonous protein and grain combinations.

U.S. manufacturers began mass-producing tomato ketchup in the late 19th century — and that processing shaped the condiment’s particular flavor profile. Early bottled ketchups fermented or spoiled relatively quickly, but industrial producers found that adding extra vinegar helped preserve them. Over time, they added more and more vinegar, and then they started adding sugar, too, to balance the vinegar’s sourness. Ketchup became more sweet and more sour than it originally had been. Americans became acclimated to this particular flavor profile of commercial ketchup — which was different from the ketchups produced by home cooks. It was thicker in texture, made with more sugar, and had a brighter, more pleasing red color (thanks to additives and preserving methods) than homemade. Industrialized ketchup began influencing other American foods. As U.S. cities grew, so did the number of diners, hamburger joints, and chicken shacks — purveyors of often greasy meals that paired very well with tomato ketchup.

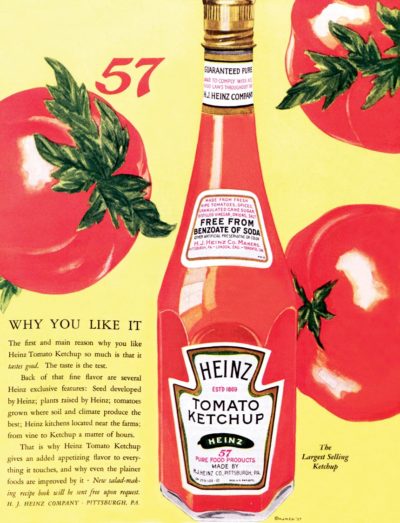

Food scientists at Pittsburgh-based H.J. Heinz Company eventually hit upon the perfect balance of sweet, salty, sour, and umami, creating a precisely calibrated product that was difficult for others to replicate — a “platonic ideal of ketchup,” as writer Malcolm Gladwell has noted. The Heinz Company displayed its wares at international expositions, spreading the gospel of ketchup throughout North America, the British Isles, and beyond.

Food scientists at Pittsburgh-based H.J. Heinz Company eventually hit upon the perfect balance of sweet, salty, sour, and umami, creating a precisely calibrated product that was difficult for others to replicate — a “platonic ideal of ketchup,” as writer Malcolm Gladwell has noted. The Heinz Company displayed its wares at international expositions, spreading the gospel of ketchup throughout North America, the British Isles, and beyond.

On the strength of its just-right recipe, as well as its manufacturing reach and global aspirations, Heinz quickly became the leading American ketchup producer, selling 5 million bottles per year by the early 1900s.

In addition to its industrial recipes, Heinz also was instrumental in developing, perfecting, and promoting sanitary production methods, not only for its ketchup but for the dozens of products it manufactured. The company helped standardize bottle and can sterilization, insisted that workers abide by strict rules of cleanliness, and even pushed for sanitary food processing legislation. Other big food processors followed Heinz’s lead. The company made ketchup, and then ketchup influenced the way everything else was processed.

It might not be too far-fetched to argue that later in the century, after altering the way American food tasted and was regulated, ketchup also helped change the way it was grown. Innovations in tomato breeding and mechanical harvester technologies, driven in part by demand for the condiment, helped define modern industrial agriculture. In the 1960s, U.C. Davis scientists developed a mechanical tomato harvester. Around the same time, plant geneticists perfected a tomato with a thick skin and round shape that could withstand machine harvesting and truck transport. This new tomato was arguably short on taste, but the perfect storm of breeding and harvesting technology from which it emerged allowed for a steady supply of tomatoes that kept bottlers and canners in business. Nearly all of the tomatoes produced for sauces and ketchup are products of this moment — as are many other fruits and vegetables produced in the U.S.

Early on, ketchup functioned as a great equalizer, with a “special and unprecedented ability to provide something for everyone.” Tomato ketchup became “entrenched as the primary and most popular of condimental sauces, its appeal to Americans deep and widespread,” writes food historian Elizabeth Rozin, who calls it the “Esperanto of cuisine.” Ketchup functioned as a class leveler. Regardless of income or education, Americans could drop into a roadside diner or barbeque joint. Affordable to most, a burger and fries spiked with ketchup was a democratic, delicious, lowest-common-denominator meal. Today, ketchup’s appeal is in part because it embodies principles that Americans prize, including consistency, value, and cleanliness. Moreover, ketchup’s use, notes Rozin, was shaped by foods and meals that are perceived as “American” in their preparation and presentation: think hamburgers and fries, “ballpark” foods, fast food in general.

The rest of the world, for better or worse, regards ketchup as emblematic of U.S. cuisine, too — and the condiment continues to shape food everywhere it goes. In Japan, people love a cuisine known as yoshoku, which they also sometimes call “Western food.” Yoshoku restaurants use a lot of ketchup. They serve a dish called naporitan, made of cooked spaghetti that is rinsed in cold water, then stir-fried with vegetables in ketchup. Omu rice is an omelet lying over a mound of ketchup-flavored rice. The hambaagu is a Japanese version of a hamburger patty, usually served bunless. Swedes love “Depression spaghetti” — ketchup poured over pasta as a sauce, as many Americans did during the 1930s and probably still do.

Today, we’re seeing the growth of artisanal ketchups that may eventually erode some of Heinz’s market share, part of the larger trend toward specialized products that feature organic ingredients, fewer artificial additives, or lower sugar levels. But industrial ketchup, with its bright red color, its vinegary and sweet flavor, and its thick texture that pairs perfectly with starches and proteins, will remain a beloved and ubiquitous condiment, influencing American eating — and increasingly, food and cooking in the rest of the world, too.

This essay originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square. It is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.

This article is featured in the January/February 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now