Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

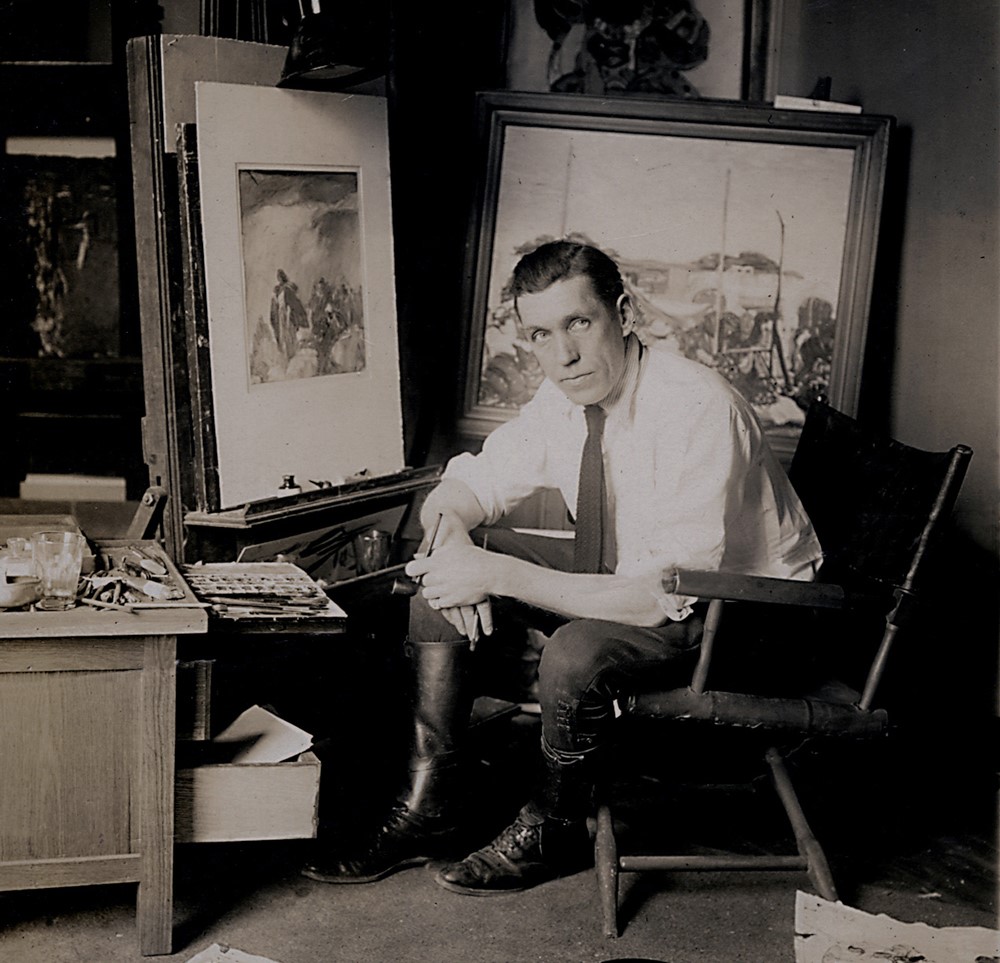

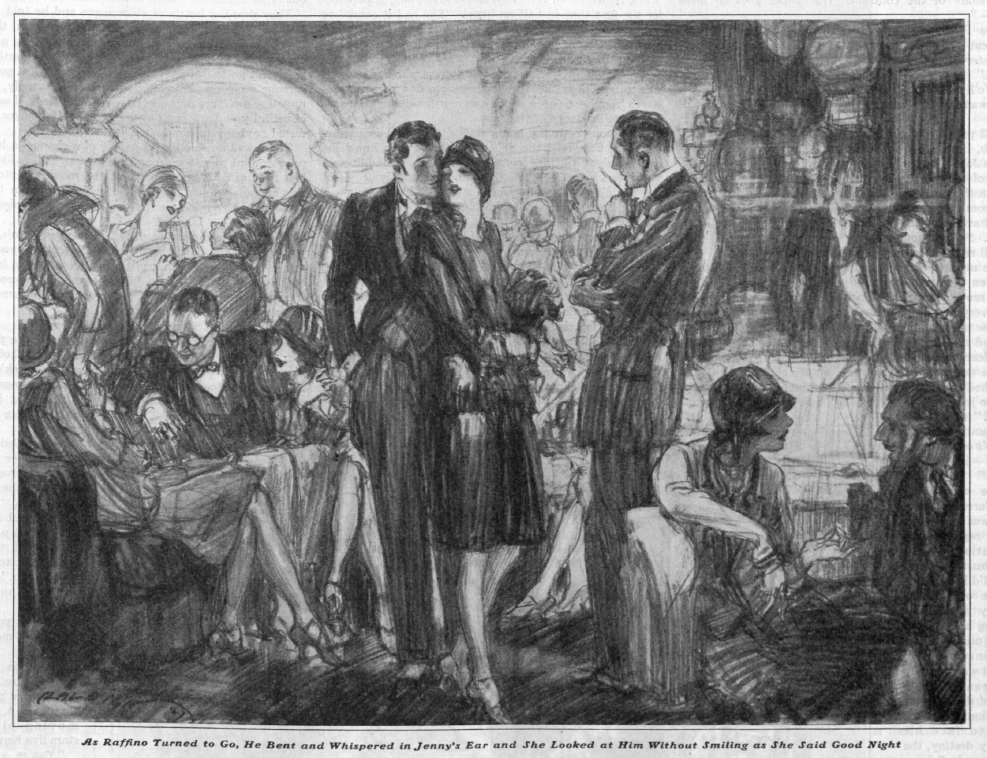

Henry Raleigh was — for a while — the most fashionable illustrator in the high society world of The Great Gatsby. He became popular and wealthy for his pictures recording glittering social parties.

He was welcomed into all the best society events. The author of The Great Gatsby himself, F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote that Raleigh’s illustrations were “the best illustrations I’ve ever seen!” Art historian Benjamin Eisenstat wrote in 1991, “Raleigh was the highest paid illustrator in America, and perhaps the world.”

And then one day, it all came crashing down.

Raleigh was born in Portland, Oregon in 1880 to a middle class family. He loved to draw, and by the time he turned twenty he was working as an artist for a newspaper. His work came to the attention of art directors and publishers at other periodicals, and he gradually received better offers from The Saturday Evening Post and other top magazines such as Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, and Colliers.

He moved to New York where he worked hard — as long as eighteen hours per day — to meet the now clamoring demands of his many clients. He was sought after by the most popular authors of his day and even received a fan letter from President Hoover. Despite the demand for his work, he always found time for the New York nightlife he loved. He was often seen out on the town, dressed in his fashionable suits and custom-tailored shirts. Tall, handsome and charming, he was adopted by Manhattan society.

This was an era before television or movies, when America relied upon magazine illustrators to conjure up the images that enhanced their daily lives. Later generations would turn to celebrity movie directors such as George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, but in these early years, celebrity illustrators of popular fiction owned the magic of popular images and were richly rewarded for their talents.

In 1912 Raleigh married the lovely young Dorothy Marion Scott. Raleigh’s grandson, Chris Raleigh, later described their ceremony: “[T]hey honeymooned on Raleigh’s new, custom built 55-foot yacht, the Aloha. They sailed to Bermuda and then on to the Caribbean where they island hopped for the next two months. Upon their return, they moved into Raleigh’s apartment overlooking the Hudson River.”

It wasn’t long before the couple moved from the apartment to a mansion in Westport, Connecticut, although Raleigh continued to work in his large studio in downtown Manhattan.

Raleigh worked quickly and was so prolific that at his peak, he was able to make enough money from just three or four months of work that he was able to spend the balance of the year taking his family and friends on world travels. American Artist magazine later described Raleigh’s charmed life and commercial success:

With distinction came affluence. In his best years his annual take was in the neighborhood of $100,000. Considering the then value of the dollar and the relatively insignificant tax on income, Raleigh probably had more cash in hand at the end of the year than any other illustrator before or since.

But Raleigh also spent money freely. He gave away thousands of dollars to friends, traveled lavishly, maintained his yacht, and owned his mansion in addition to a large studio in downtown Manhattan. As part of his fast life, he divorced his wife in 1928 to marry a Ziegfeld girl, Mary Holly McDonald.

Raleigh created popular illustrations for The Post for over 20 years. But by the late 1930s times and tastes were changing. The Post hired new editors with new approaches — first Wesley Stout in 1937 and then Ben Hibbs in 1942. These editors both took steps to update the look of the magazine.

Styles were changing at the other magazines as well. At the end of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II, the public’s enthusiasm for glittering parties had diminished. Public taste in art had changed, too, over Raleigh’s thirty-year career. It didn’t help that photography began to replace painted illustrations and eroded what little was left of Raleigh’s client base. Assignments were reduced to a trickle. He could not adapt. As grandson Chris wrote, “Raleigh’s health was failing. He had wrongly assumed he would always find work as an artist so he never saved or had a plan for retirement.”

Unlike fine art painters, illustrators who paint for weekly or monthly periodicals must repeatedly win approval. In each new issue of a magazine, the art director makes a fresh assessment of whether an illustrator will be popular with readers. Once the fan mail starts to decline or the advertisers start to request a “new look,” the illustrator’s days are numbered. No fine artist in a museum or gallery was ever held to such a rigorous test of their work.

Like other illustrators before and after him, Raleigh was caught in this recurring, unforgiving test. He became increasingly depressed, for he had lost not only his income, but his adoring fan base. In the end, bankrupt and bitter, Raleigh could not handle the changing times. He tragically ended his own life in 1944 by jumping out of the window of a cheap hotel in Times Square. Meanwhile, the next generation of young, talented illustrators were arriving with their own innovations and new styles

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

There is more to the story, but one thing I’d like to focus on: Holly’s name. I have had her surname labeled McDonald, Wilcox, and Beckwith (the latter was given to me by Holly’s grandson). Note that Chris Raleigh is Dorothy’s grandson.

Fascinating look at a tremendous artist but I must chastise the author for the lazy UNINSPIRED closing sentence. You couldn’t think of a more thoughtful or elegant way to end tgis piece? Raleigh deserved better than THIS.

Thanks for this wonderful feature on this gifted artist, Henry Raleigh. The examples shown here, show the vast variations of his styles. I can’t help but wonder to what extent his ’20s life in the fast lane of being rich and famous, plus the fiscal irresponsibility of those “it’ll never end” years contributed to his own cascading downward crash when things started drying up in the late 1930’s.

Just looking at the ’27 illustration here for Fitzgerald, I see an illustrator clearly ensconced in depicting a situation all too familiar to him in real life. By illustrating it to perfection like this, he was also becoming further hard-wired and addicted to this unsustainable lifestyle as well. I love the almost abstract look of the “blue” painting at the top. I can’t help but think he didn’t influence my favorite modern illustrator, Bob Peak. Oh yes, I see it clearly in the ladies’ gowns.

$100,000 a year at his peak was A LOT of money then. That’s several million now, at least. The yacht, the mansion, the large Manhattan studio and more weren’t enough assets to save him when things started to dry up. I doubt any of the friends he generously gave money to ever offered to help him out when he needed money, or asked for it as he began sinking into dire straits.

It’s no accident (or fault) The Saturday Evening Post went through a period of turmoil between 1937 and ’42. LIFE magazine’s appearance in late 1936 had to have been like a major earthquake, then World War II not long after that. By May 1937 the Post was starting to use photo covers here and there, and by 1942 changed its logo to basically ‘POST’, also in the upper left hand corner. Fortunately this format worked (with the famous art covers) until late 1961 and ’62, with photos taking over completely in 1963.

By other magazines, you’re probably referring to Collier’s and Liberty. LIFE and World War II had them scrambling for more sure footing too, with frequently changing logos and using photography covers a lot more. I feel terrible Raleigh committed suicide. No money, no fans, no hope. It’s an all too familiar story of not knowing when you’ve got it good, and not preparing for when those times end.

David, did you get the copy of the letter DMB&B sent me regarding AF VK I sent you fairly recently? It’s important. Please review and advise. Thanks.