If you grew up in a suburb, attended college, own a home, or consider yourself to be “middle class,” there’s a good chance you’re the beneficiary of the G.I. Bill of Rights.

Its official name was the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, and its original goals were modest: to help veterans move from the military back to civilian life after World War II. And, if possible, to avoid the unemployment and recession that usually came at war’s end.

The Bill did far more than that. Its benefits made a new life for the wartime generation and improved the opportunities for their children and grandchildren.

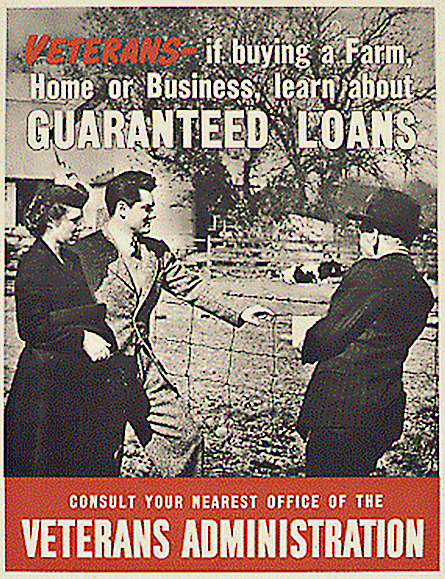

Signed into effect by President Franklin Roosevelt on June 22, 1944 — just two weeks after D-Day — it provided veterans help in buying a home, setting up their own business, starting a farm, going to college, learning a trade, finishing high school, or getting a government job.

For the veteran coming home after years of service, wondering if he’d get his old job back, wondering if the depression would return, the Bill made their future look a lot more promising.

The Opportunity to Choose

Discharged World War II veterans could obtain unemployment compensation at today’s equivalent of $284 a week for 52 weeks. The money removed the need to accept the first job offered them. They now had time to consider a different future. Congress had ordered employers to offer G.I.s their old jobs back, but, according to the book Days of Sadness, Years of Triumph by historian Geoffrey Perrett, 70% of veterans didn’t want them. War had changed them and many wouldn’t be content with their old dreams.

Before the war, many of the G.I.s had held low-skilled jobs, which they never expected to escape. A blue-collar worker might spend his life performing the same work as his father and grandfather. Now, if he had bigger dreams than this, government benefits would give him time to explore them.

This part of the G.I. Bill was strongly contested in Congress. Some legislators opposed the benefits, believing that veterans would simple take the money and avoid work for as long as possible. But this wartime generation proved them wrong. By the end of the program, the Veterans Administration had paid veterans less than 20% of the total budget allotted for this program.

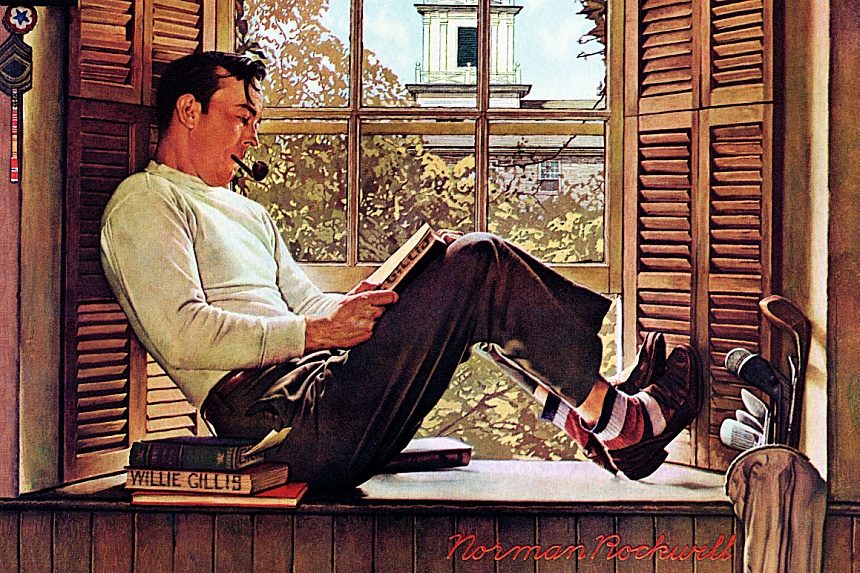

A Tradition of Higher Education

Before the war, only one third of Americans had finished high school. And most of those who’d completed 12 years of schooling had little idea of further education. College was unthinkable. It was popularly thought to be the preserve of the elite, a place where richer, smarter people advanced their careers.

But now the G.I. Bill would pay for up to four years of veterans’ college tuition, text books, career counseling, and a living allowance.

The early response was minimal. In an article called “The GIs Reject Education” from the August 18, 1945 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, the writer reported that less than one percent of early discharged veterans were taking advantage of the educational aid. Many said they just wanted to get back to their old jobs. But a later wave of discharged veterans had more time to learn more about their new benefits. They crowded into the admissions offices of state colleges and universities.

By the next year, the Post went to the University of Illinois and found “veterans living in basements, veterans in garrets, veterans in made-over garages and abandoned filling stations. There were 300 sleeping in double-decker beds in the gaunt building known as the Old Gymnasium Annex.” [“Crisis at the Colleges” August 8, 1946]

By 1947, half of all college admissions were veterans. Ultimately, 2.2 million veterans used the program to attend college. Another 3.4 million used the money to complete high school or, in some cases, grade school.

Colleges became more familiar to Americans and more accessible. Veterans saw the benefits of a college diploma and expected their children to follow their example.

Wanting to take meet demand, colleges began to expand, adding more departments and building more dormitories and class rooms. They expected enrollment to remain high into the future. It was, ultimately, by the children of veterans.

A Smarter Population

The millions of veterans who took advantage of a free college education helped raise the productivity of the American work force and bring it into the space age. They provided the technical expertise that revolutionized electronics, computers, aeronautics, media, and business management. They also found employment on major new government projects, like the interstate highway system and the space program.

The education benefits also helped some veterans to make outstanding contributions to American society. These included 14 Nobel prize winners, three Supreme Court justices, three presidents, a dozen senators, and 24 winners of the Pulitzer Prize.

A Bigger Middle Class

Veterans from what had been classified as “working class” families were now taking jobs at Fortune 500 companies, like IBM and Boeing. They had moved into the middle class, and they expected their children and grandchildren to remain there.

One sign of arriving in the middle class was home ownership. Since 1900, the percentage of Americans who owned homes hovered around 40 percent. Twenty years later, it had stabilized in the 60 percent range.

In 1946, with veterans’ home loans guaranteed by the government, there was a 300 percent increase in housing starts. Almost half were purchased with VA loans.

The loans were limited to $2,000 at first, but later the limit was raised to $4,000, then $7,500, indicating that veterans expected to afford even more elaborate homes.

This new burst of home construction spread the money among construction workers, who, in turn, passed it on to retailers and others, to become an important part of the postwar economy.

The G.I. Bill had a different history for black veterans. Few were able to secure mortgages; many banks had policies of refusing home loans to minorities. Minority veterans were also blocked from buying houses in neighborhoods where they could now afford to live. Colleges and universities that principally served black Americans were quickly overcrowded and had to turn away student applicants. Overall, the G.I. Bill made only a small difference for the black soldiers coming home.

The G.I. Bill can’t take all the credit for the growth of America’s middle class. The revival of the auto industry, with well paid jobs for thousands, also played a big role. So did the fact that the U.S. was the only working industrial economy in the world.

But the 1950s’ prosperity wouldn’t have been possible without millions of veterans who had upgraded their skills with the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act. And set a new standard of living for themselves and their children and grandchildren. who now represents at least 30% of Americans

Featured Image: Willie Gillis goes to college on the G.I. Bill by Norman Rockwell (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now