Executive privilege is the president’s right to keep certain information secret from the other branches of government, even if the information is subpoenaed.

But where did executive privilege come from?

You won’t find it mentioned anywhere in the Constitution. It has been assumed from Article II, which sets out the separations of powers in the three branches of government. In order to maintain a balance of power, the reasoning goes, the president need to be able to consult with his advisors and develop his policies beyond Congressional observation.

But executive privilege won’t cover just anything. It must relate to national security or protecting White House confidentiality when in the public interest.

In the past, the courts have made decisions that defined executive privilege. But taken together, they give only a vague sense of what the privilege covers and when can it be used.

In 1789, Congress investigated a military campaign against Native Americans that ended in disaster. It asked for documents from President George Washington. The president argued that he could refuse a request for documents in the name of national security. In time, though, he handed them over.

When Aaron Burr went on trial for treason in 1809, his defense subpoenaed President Thomas Jefferson to testify and supply papers related to the charges in Burr’s trial. Jefferson refused. The Supreme Court said he had to comply. In the end, he refused to testify in person but provided select documents.

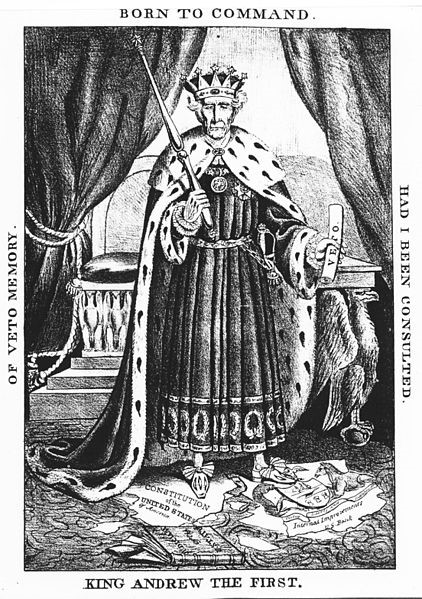

In 1833, Senator Henry Clay demanded that President Andrew Jackson release documents about cabinet meetings where the Bank of the United States was discussed. Jackson declined and was censured, but held onto the documents.

President Grover Cleveland used it repeatedly to prevent Congress from reviewing documents related to his executive appointments to government positions.

When President Theodore Roosevelt prosecuted U.S. Steel for antitrust violations, the Senate demanded to see his papers on the subject. Roosevelt denied the request, then moved the documents to the White House to prevent their being seized.

It was President Dwight Eisenhower who coined the term “executive privilege.” He invoked it to prevent Senator Joe McCarthy from questioning his cabinet members. Eisenhower wanted to maintain the secrecy of conversations he had with his advisors about McCarthy and communists. He also wanted to keep sensitive documents from public view. In the course of Eisenhower’s presidency, he or his advisors invoked executive privilege 44 times.

Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson rarely used it, but President Richard Nixon relied on it to protect himself and his advisors from the Watergate investigation. A challenge to his use of the privilege went to the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Warren Burger said executive privilege was warranted when the requested information concerned “military, diplomatic, or sensitive national security secrets.” But it didn’t provide protection from a criminal investigation. Documents and testimony crucial to the inquiry had to be provided. Consequently, Nixon released the tape-recorded conversations from the Oval Office. “The president is not above the law,” said the Chief Justice.

Nixon seems to have cast executive privilege in a bad light, because subsequent presidents were wary of using it. Even when a Congressional investigation into the Iran-Contra matter led to the White House, President Ronald Reagan did not invoke it.

President Bill Clinton cited executive privilege 14 times to spare himself and his wife from testifying in Congressional investigations of his business dealings and sex life. The Supreme Court ruled that a prosecutor’s right to investigate matters was more important than confidentiality. Ultimately, Clinton was impeached by the House of Representatives, but the Senate did not convict him.

When the Senate Judiciary Committee subpoenaed Karl Rove in an inquiry into the firing of nine U.S. attorneys, President George W. Bush refused, citing the privilege. The committee chair said it didn’t apply because the president wasn’t involved. Ultimately, Rove testified in a closed-door session.

In 2012, an investigation into drug smuggling misfired and resulted in a load of guns getting into the hands of criminals. Congress requested the White House hand over 1,300 documents. President Obama claimed executive privilege, and his attorney general was cited for contempt of Congress for not cooperating. When the matter went to a federal court, the claim of executive privilege was denied and the documents were released.

The case law would indicate that there is no privilege if the matter involves a criminal investigation and doesn’t directly bear on the national welfare. But it appears that the final call isn’t usually made by the president, the media, or legislators, but the nine members of the Supreme Court.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I really had no idea how far back ‘Executive Privilege’ went, or how (comparatively) recent the term itself was. It seems justified with the earliest Presidents, up through Eisenhower. With Nixon (as I’ve said before) had he spun the Watergate break-in as an unfortunate necessity regarding national security, not covering it up, he wouldn’t have had to claim executive privilege. He would have been seen as protecting the American public from a potential threat that, thank God, turned out to be a false alarm. The real crime was the cover up, and his insecurities to ordering the damn break-in in the first place, so my ‘save’ ideas wouldn’t have even been necessary, Jeff!

Clinton should have been forthright and honest about his ‘personal weaknesses’ and apologized to his wife, family and the American public for this shameful embarrassment. That would have neutralized Ken Starr and the whole mess otherwise. Knowing when to be humble and contrite is one of life’s BASIC lessons!

As for the current situation, it’s sooo far out and crazy I couldn’t begin to speculate as to ANY outcome, OR rule out his remaining in office through 2024 either.