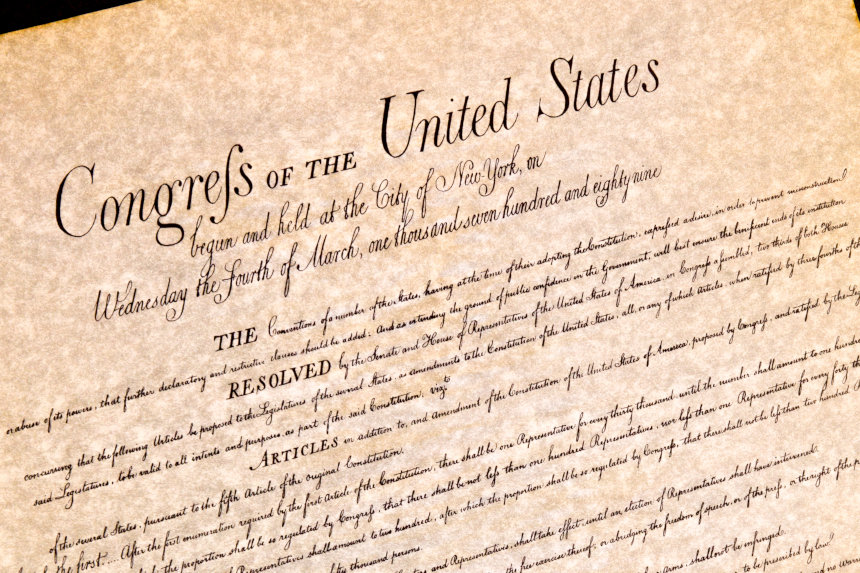

In 1789, two years after the Constitution was approved, Representative James Madison proposed 20 additional amendments to the Constitution that would protect individual liberties — the Bill of Rights. When he finally presented them for Congressional approval, there were only 17.

Congress removed some and combined others, finally approving 12 amendments for voters in the states to ratify. All but two were approved.

Lost was the original First Amendment, which established a formula for calculating the size of the House of Representatives based on the growing population. It was meant to ensure that small constituencies would continue to be represented and not get lost in giant congressional districts.

Under the original First Amendment, the number would be increased every ten years based on the national census. Had this amendment been approved, the House of Representatives would today have anywhere between 500 to 8,000 members, depending on how the Supreme Court interpreted the law. (Its membership is currently set at 435.)

This amendment didn’t receive enough votes, nor did the Second Amendment, which spelled out the distinction of powers between the different branches of government:

The powers delegated by this Constitution are appropriated to the departments to which they are respectively distributed: so that the Legislative Department shall never exercise the powers vested in the Executive or Judicial, nor the Executive exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Judicial, nor the Judicial exercise the powers vested in the Legislative or Executive Departments.

Congress discarded it, but saved the second paragraph of this amendment, making it the Tenth Amendment: “The powers not delegated by this constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively.”

One of Madison’s original 17 amendments wanted to ensure each state protected their residents’ liberties. “No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.”

But Congressmen didn’t feel this was necessary. They also combined two of Madison’s original 17 amendments. One guaranteed freedom of religion, and the other protected freedom of speech, press, assembly, and right to petition.

Congress also altered what became our Second Amendment. Its original wording said,

“The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country: but no person religiously scrupulous of bearing arms shall be compelled to render military service in person.”

Madison also wanted to insert the Declaration of Independence before the Preamble, but Congress didn’t approve. It would have buried the memorable phrase that began the Constitution — “We the People…” in the text.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Bob McGowan Jr,

Yes some of our founding fathers would be ashamed and horrified, others unfortunately were the beginning catalyst of what is happening now.

It’s definitely time to take back our countries.

Thank you Jeff, for this article. Thank YOU God for not letting the Founding Fathers of this country see the state it’s in today. They did their best, but it’s all being dismantled on a daily basis which is frightening.