It was December 18, 1944, and I was dressed for success. A black suit and high heels — sling pumps to be specific. They did not have the stiletto heels of today so I was at no risk of them catching in the wood planks of the Madison Street Bridge as I crossed the Chicago River, a streetcar passing by making the planks quiver. On the far side, what is now considered an Art Deco building worthy of historic preservation, was the Chicago Daily News Building. My destination: the seventh floor, where the editorial offices of the Chicago Sun were located.

It was still the Chicago Sun, not yet merged with The Times a few blocks up the river, and still in the Daily News Building, where it had originated. It had been given space by the then owner and publisher of the Chicago Daily News, Colonel Frank Knox. Knox had offered the space to Marshall Field III so he could start his paper before he built a building to house it. Alas, the paper’s first issue came out on a Sunday — a Sunday noted not for its publication but an event halfway around the world: The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

The war was still part of the story on the day I headed for the Daily News Building in hopes of getting a job. My first.

I was 18. My father had had a heart attack the previous month, and it was thought he would never work again. So I waited for the quarter to end at Northwestern and headed for the Chicago Sun offices in hopes of becoming a copygirl, like the girl who sat next to me in my newswriting class in the Medill School of Journalism.

When I stepped off the wood planks of the bridge and onto the concrete sidewalk I came face to face with a newsstand — a small building, close kin to a garden shed, with a wide open front that displayed the newspapers of the day. Chicago had six daily newspapers then. And the headlines were on the latest battle, a surprise attack by the Germans, in the Ardennes. It would come to be known as The Battle of the Bulge.

That battle was one of the events of World War II that would define so much of the 20th century. And although I did not know it as I walked past the newsstand, it was also responsible for my success that day.

The war had so drained the pool of young men that copyboys were in short supply and the Daily News had decided to take girls without the slightest hesitation or delay. The first words out of the director’s mouth after he told me I was hired were: “Can you start tomorrow?” I could, and when I reported for work the next morning at 9:00, I became, according to an editor some months later, the first copygirl at the venerable Chicago Daily News — “the grey old lady” of Chicago journalism.

That explained, in part at least, why for days — indeed, well into my second month — reporters scattered throughout the city room would often call out “Boy!” even while looking straight at me. It was only later that I realized the cry of “Boy!” was synonymous to them with the cry of “Copy!”

To say that the city room was a male bastion is to say that the sun rises in the east. There were five or six women reporters, temporary replacements for the men who had gone off to serve their country. There were no women in the departments off the city room, and certainly none in the Man Cave of Man Caves, the sports department. True, there was a Woman’s Page section at the end of another corridor, but it was like a detached garage.

I’d only seen editors and reporters at work in the movies, where they yelled “Scoop! Scoop!” and “Stop the presses!” Now I was in the city room of one of the great newspapers in American journalism history. Many of the editors and reporters were legends even then. One of the most famous stories of World War II was written by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News Foreign Service — an account of the emergency appendectomy performed aboard a submarine deep in enemy waters. It would win the Pulitzer Prize. And the Chicago Daily News itself would win, in the same period of time, almost as many Pulitzer Prizes as The New York Times.

My first week I faced rowdy encounters when I went to the sports department to deliver proofs. It was days before Christmas and the holiday spirit there was largely bottled. One time someone, I think it was the sports editor, told them to tamp it down. And they did. But I was so uncomfortable as the days went on, I finally asked the director of copykids to have the boys deliver the proofs to the sports department, and he did … or took them himself. When we returned after Christmas, all was well.

Other than that, I was only subjected to a couple of crude/rude remarks in eight years at the Daily News. It may be that I fared so well because, being 18, in my saddle shoes and pleated plaid skirts, I was everyone’s kid sister or daughter. And I’m not aware of any sexual harassment of the women reporters. I may have missed it, but I think they were simply accepted because everyone knew that when the war ended and the guys returned, they’d be gone. It was a matter of law, writ, on the books, that when those who’d served their country returned, their jobs were there, waiting for them, as surely as their loved ones.

When that time came, two of the women were retained, one in the city room as a reporter — she’d become a star — and one moved down the hall to the features section to take over the daily radio column, there being no television yet. The rest went off to smaller newspapers, back to where they’d been before the war … but with highly polished credentials.

By then, I’d moved up to the picture desk as an assistant and member of the staff, part of the apprentice system in place for years with boys. In January 1946 I started a column — for high school and college students, as befit my age — and was no longer in the city room. I was housed at first in the women’s page offices and, then, the ever expanding features section.

One woman in the city room my first day — and last — was Margaret Whitesides. She sat at the city desk — a female hole in the donut of editors. She answered the phones, opened the mail, kept track of the notices of upcoming events. Her father was a printer in the composing room on the fifth floor, as was her brother, but she had come to work at the Daily News as a secretary in one of the business offices on the fourth floor. She yearned, however, to be in the city room. When the now legendary Clem Lane became city editor, it came to pass.

She would stay there through the comings and goings of scores of men and women whose names are woven into the history of the Chicago Daily News, a quiet, friendly face amidst the editorial storms that struck almost daily. And when the Daily News ceased to be, Margaret started a newsletter a few years later. She wrote it on the old Underwood typewriter she’d used for so many years, and was allowed to take when the paper closed.

It has come to be more than a vehicle for catching up or keeping up. It has come to be a repository of journalism history. So much so a complete set is part of the growing Chicago Daily News Collection at the Newberry Library.

The June-July issue this year noted the passing of one of the most famous women to ever have a byline in the Chicago Daily News, Georgie Anne (“Gee Gee”) Geyer. Written by Rick Kogan, a Daily News alum who’d moved to the Chicago Tribune some years before, he said:

In an era when a woman in a newsroom was, as her friend Mike Royko once put it, “as rare as a teetotaler,” Georgie Anne Geyer not only made her mark as a foreign correspondent and syndicated columnist, but also became an inspiration to generations of women who followed in her globe-trotting footsteps.

How hard that was is suggested by the story’s subhead: “‘She’s nuts,’ we laughed when Gee Gee said she wanted to be a foreign correspondent.”

The August-September issue looked back on the career of Lois Wille, “pioneer on many frontiers.” Said editor Jack Schnedler:

The Daily News newsroom was almost totally a man’s world in 1957 when Lois Wille reported for duty from the paper’s so-called “women’s pages.” The city’s only other female reporter covered the traditional distaff beat of education.

One reporter introduced himself by bending down and rubbing Wille’s ankle. As she later told it, she rebuffed the offending jerk by shouting loudly, for everyone in the newsroom to hear: “Jack, that’s my ankle!” She was never manhandled again.

They, like Margaret, the copygirls who came after me and, however slowly, the women who followed the war time “temps,” were part of the revolution described by Schnedler as “so seismic that most newsrooms today – in print journalism’s twilight – are staffed by as many or more women than men. And women in top editor’s positions are no longer rarer – pardon the lame simile – than hen’s teeth.”

My first weeks, I was often teased. Still so young I yearned to be older, I chafed at always being told to “Take this to this to the copy desk, like a good little girl,” or “Get the clips on the mayor from the library … that’s a nice child.” One day I blurted out: “I’ll be 19 … three weeks from next Tuesday!” City Editor Clem Lane took a step back, surprised, but recovered nicely. “Then you’d better hurry … before Social Security gets you.”

I also tried the patience of many an assistant editor when I was granted the opportunity to start learning to be a reporter. I particularly remember one effort coming back with the comment: “Please, Val. Not Bow Wow. The Chicago Kennel Club announced the opening of its annual dog show ….”

But when I went out with a photographer to cover my first story, and then was told to take it on to the copy desk, the guys there were so happy for me. “We hear you wrote this,” they said. To which I happily replied, “I did. I did!”

Much water has passed under the bridge since that December day I crossed the Madison Street Bridge, the wood planks quivering when a streetcar rumbled by, my dressed for success high heels in no danger of being caught as I headed for the Chicago Daily News Building … and my entry into, to me, the hallowed walls of The Fourth Estate.

A long time ago, now.

But I was there, if not at the Creation, the beginning.

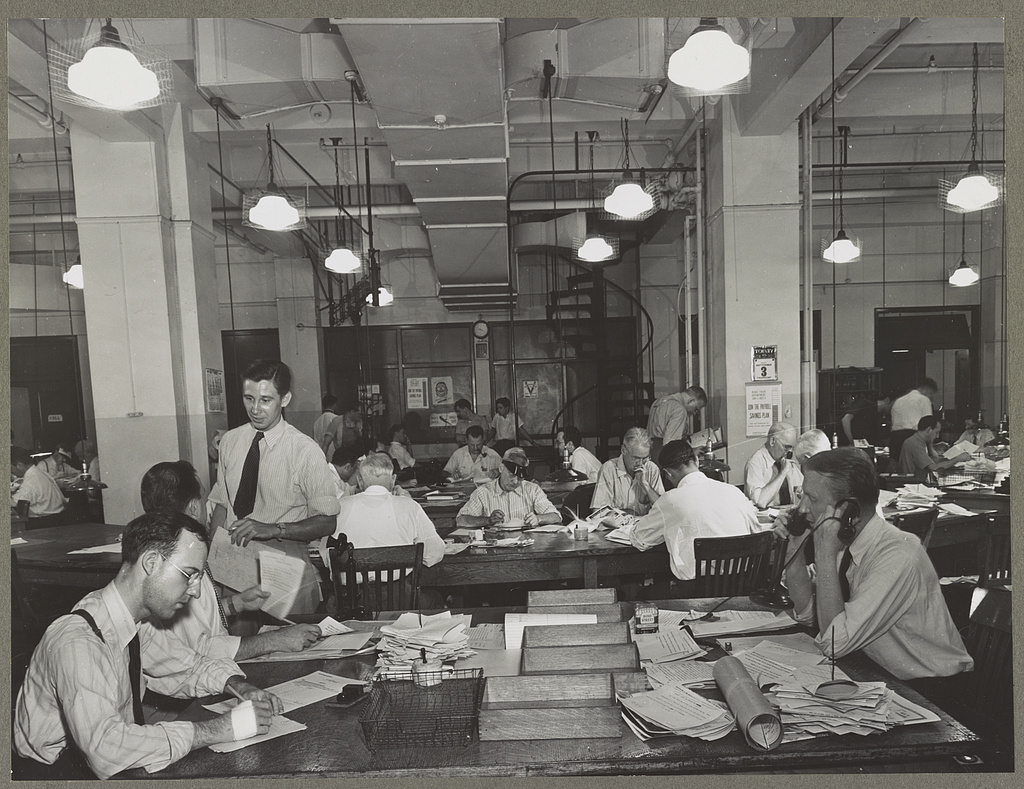

Featured image: Val Lauder handing off copy to a copyboy in 1947 at the Chicago Daily News. (Used with permission of Eileen Darby Images, Inc.)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great article! I love reading these slices of history from people who were there.

Ms. Lauder, I love this first-hand, “insider” look at the nitty gritty aspects of being a young female journalist during World War II. I was so pleased with your recent story of how you coped and managed with the losses and adversities you faced during the war, never feeling sorry for yourself.

This “chapter” shows how you put your skills, intelligence and common sense into practical use on the job, taking advantage of the opportunities as they presented themselves, while also turning lemons into lemonade! I like how you kept the men in their place, and the way Lois Willie called one of them out—in front of everyone!

You have an amazing, sharp writing style to this very day I love as well. More and more it’s becoming clear that the best “man” for the job IS a woman. You definitely helped pave the way for women like Martha Raddatz, and (obviously) the Post’s own Joan SerVaas; both women the gold standards of their respective journalistic fields! I hope you have more stories of your past to tell, because they have so much to say in the present, AND they’re wonderful–like you! Thank you, and so many other Americans of your incredible generation.