Kentucky author James Lane Allen wrote novels and stories celebrating his home state, its people and dialect. His story “The Last Christmas Tree” was published in The Saturday Evening Post before he expanded it into a book-length story dedicated to “those who know they have no solution of the universe yet hope for the best and live for it.”

Published on December 25, 1908

The stars burn out one by one like candles in too long a night.

Children, you love the snow. You play in it, you hunt in it; it brings the tinkling of sleighbells, it gives white wings to the trees and new robes to the world. Whenever it falls in your country, sooner or later it vanishes: forever falling and rising, forming and falling and melting and rising again — on and on through the ages.

If you should start from your homes and travel northward, after a while you would find that everything is steadily changing: the air grows colder, living things begin to be left behind, those that remain begin to look white, the music of the earth begins to die out; you think no more of color and joy and song. On your journey, and always you are traveling toward the silent, the white, the dead. And at last you come to the land of sunlessness and silence — the reign of snow.

If you should start from your homes and travel southward, as you crossed land after land, in the same way you would begin to see that life was failing, colors fading, the earth’s harmonies being replaced by the discords of Nature’s lifeless forces, storming, crushing, grinding. And at last you would reach the threshold of another world that you dared not enter and that nothing alive ever faces—the home of the frost.

If you should rise straight into the air above your housetops, as though you were climbing the side of an unseen mountain, you would find at last that you had ascended to a height where the mountain would be capped with snow. All round the earth, wherever its mountains are high enough, their summits are capped with the one same snow; for above us, everywhere, lies the upper land of eternal cold.

Some time in the future, we do not know when, but some time in the future, the Spirit of the Cold at the north will move southward; the Spirit of the Cold at the south will move northward; the Spirit of the Cold in the upper air will move downward to meet the other two. When the three meet there will be for the earth one whiteness and silence — rest.

A great time had passed — how great no one knew; there was none to measure it.

It was twilight and it was snowing. On a steep mountainside, near its bald summit, thousands of feet above the line that any other living thing had ever crossed, stood two glorious fir trees, strongest and last of their race. They had climbed out of the valley below to this lone height, and there had so rooted themselves in rock and soil that the sturdiest gale had never been able to dislodge them; and now the twain occupied that beetling rock as the final sentinels of mortal things.

They looked out toward the land on one side of the mountain; at the foot of it lay a valley, and there, in old human times, a village had thriven, church spires had risen, bridal candles had twinkled at twilight. On the opposite side they looked toward the ocean—once the rolling, blue ocean, singing its great song, but level now and white and still at last — its voice hushed with all other voices—the roar of its battleships ended long ago.

One fir tree grew lower down than the other, its head barely reached up to its comrade’s breast. They had long shared with each other the wordless wisdom of their race; and now, as a slow, bitter wind wandered across the delicate green harps of their leaves, they began to chant — harping like harpers of old who never tired of the past.

The fir below, as the snowflakes fell on its locks and sifted closely in about its throat, shook itself bravely and sang:

“Comrade, the end for us draws nigh; the snow is creeping up. Tonight it will place its cap upon my head. I shall close my eyes and follow all things into their sleep.”

“Yes,” thrummed the fir above, “follow all things into their sleep. If they were thus to sleep at last, why were they ever awakened? It is a mystery.”

The whirling wind caught the words and bore them to the right and to the left over land and over sea: “Mystery — mystery — mystery.”

Twilight deepened. The snow scarcely fell; the clouds trailed through the trees so close and low that the flakes were formed amid the boughs and rested where they were created. At intervals out of the clouds and darkness the low musings went on:

“Where now is the Little Brother of the Trees — him of the long thoughts and the brief shadow?”

“He thought that he alone of earthly things was immortal.”

“Our people, the Evergreens, were thrust forth on the earth a million ages before he appeared; and we are still here, a million ages since he left, leaving not a trace of himself behind.”

“The most fragile moss was born before he was born; and the moss outlasted him.”

“The frailest fern was not so perishable.”

“Yet he believed he should have eternal youth.”

“That his race would return to some Power who had sent it forth.”

“That he was ever being borne onward to some far-off, divine event, where there was justice.”

“Yes, where there was justice.”

“Of old it was their custom to heap white flowers above their dead.”

“Now white flowers cover them — the frozen white flowers of the sky.”

It was night now about the mountaintop — deep night above it. At intervals the communing of the firs started up afresh:

“Had they known how alone in the universe they were, would they not have turned to each other for happiness?”

“Would not all have helped each?”

“Would not each have helped all?”

“Would they have so mingled their wars with their prayers?”

“Would they not have thrown away their weapons and thrown their arms around one another? It was all a mystery.”

“Mystery — mystery.”

Once in the night they sounded in unison:

“And all the gods of earth — its many gods in many lands with many faces — they sleep now in their ancient temples; on them has fallen at last their unending dusk.”

“And the shepherds who avowed that they were appointed by the Creator of the universe to lead other men as their sheep — what difference is there now between the sheep and the shepherds?”

“The shepherds lie with the sheep in the same white pastures.”

“Still, what think you became of all that men did?”

“Whither did Science go? How could it come to naught?”

“And that seven-branched golden candlestick of inner light that was his Art — was there no other sphere to which it could be transferred, lovely and eternal?”

“And what became of Love?”

“What became of the woman who asked for nothing in life but love and youth?”

“What became of the man who was true?”

“Think you that all of them are not gathered elsewhere — strangely changed, yet the same? Is some other quenchless star their safe habitation?”

“What do we know; what did he know on earth? It was a mystery.”

“It was all a mystery.”

If there had been a clock to measure the hour it must now have been near midnight. Suddenly the fir below harped most tenderly:

“The children! What became of the children? Where did the myriads of them march to? What was the end of the march of the earth’s children?”

“Be still!” whispered the fir above. “At that moment I felt the soft fingers of a child searching my boughs. Was not this what in human times they called Christmas Eve?”

“Hearken!” whispered the fir below. “Down in the valley elfin horns are blowing and elfin drums are beating. Did you hear that — faint and far away? It was the bells of the reindeer! It passed: it was the wandering soul of Christmas.”

Not long after this the fir below struck its green harp for the last time:

“Comrade, it is the end for me. Goodnight!”

Silently the snow closed over it.

The other fir now stood alone. The snow crept higher and higher. It bravely shook itself loose. Late in the long night it communed once more, solitary:

“I, then, close the train of earthly things. And I was the emblem of immortality; let the highest be the last to perish! Power, that put forth all things for a purpose, you have fulfilled, without explaining it, that purpose. I follow all things into their sleep.”

In the morning there was no trace of it.

The sun rose clear on the mountaintops, white and cold and at peace.

The earth was dead.

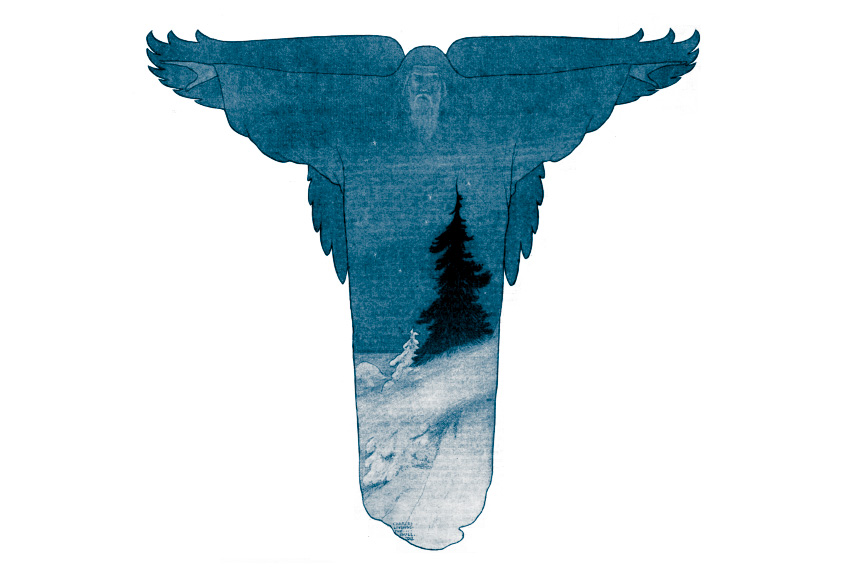

Featured image illustrated by Charles Livingston Bull

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you for this interesting, well told, thought provoking story, Nicholas. I like the way the author writes and speaks. Wise words that resonate even more strongly in the foolish present, especially at this time of year.

All the more reason to wish everyone safe and Happy Holidays.