In July of 1951, the U.S. Public Health Service created a new organization, the Epidemic Intelligence Service. The service tasked a small band of epidemiologists with finding and stamping out eruptions of communicable diseases — including polio, influenza, and typhoid — before they became full-blown epidemics.

Originally meant to be used to detect and stop early signs of biological warfare during the Korean War, the EIS became an invaluable tool in the fight against communicable diseases. The service was created by CDC epidemiologist Alexander Langmuir. He and his staff developed national tracking programs not only for many communicable diseases, but also for chronic diseases, injuries, and reproductive health.

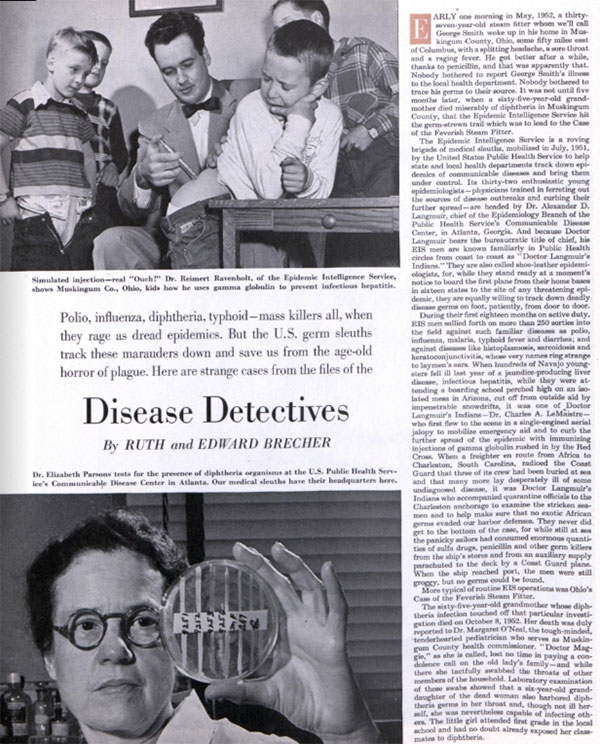

The idea behind EIS was to practice “shoe leather epidemiology” – that is, to send smart folks to where there were disease outbreaks and have them track the origin and spread of the disease so they could contain it. Often, their work included painstakingly going door to door.

The Saturday Evening Post wrote about the EIS in 1953 and the meticulous work of the EIS officers, who uncovered a diphtheria outbreak in Ohio, pieced together the common features among 14 different histoplasmosis clusters, and found the true culprit behind Western equine encephalitis.

Two years after the Post article was published, the EIS solidified its reputation by applying their sleuthing skills to a potentially devastating problem. The brand new polio vaccine was causing cases of polio. In less than a week, the EIS determined that the bad vaccine was coming from a single manufacturer, averting not only the use of the polio-causing vaccine, but also the greater potential disaster of the nation rejecting the new polio vaccine altogether.

The EIS men were always kept busy, both with old enemies and novel newcomers:

One of the fascinations of life in the EIS is that you never know what’s going to erupt next. Last winter, it was the nationwide influenza epidemic. In March, EIS men were off squelching local epidemics of infectious hepatitis. And in April they were out after anthrax once more — this time in North Carolina. This coming summer, no doubt, they will be busy with polio again.

The EIS is still practicing its shoe leather epidemiology, acting as first responders to disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and other public health emergencies in the U.S. and abroad. According to a profile of Langmuir by Myron G. and William Schaffner, the organization has “played pivotal roles in combating the root causes of major public health problems. Millions of persons live longer and healthier lives because of the accomplishments of Langmuir and his progeny in controlling and preventing disease.” To date, the EIS has trained more than 3,500 doctors and other health workers. Today, many of the EIS officers are working hard to track and understand COVID-19. Though it’s ironic that their own annual conference was cancelled due to coronavirus, that bump in the road hasn’t slowed down the ongoing work of the nation’s foremost disease detectives.

Featured image: “Disease detective” Reimert Ravenholt and Dr. Margaret O’Neal follow up on a diphtheria scare by searching for germ carriers in a Muskingum County school. Photo by Harry Saltzman for The Saturday Evening Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Perhaps we were bit late in understanding the scope and dangers of coronavirus. The WHO initially considered it to be less dangerous than 2003 epidemic SARS. But it has proved to be most dangerous viral infection in decades.