There’s nothing more Hawaiian than the sound of a ukulele, strummed under palm trees to the accompaniment of grass-skirted hula dancers. Since the 1880s, this instrument has been a symbol of island life, played in the 19th century royal court, printed on postcards, performed at tourist luaus, and brought home as souvenirs by visitors — including the likes of Robert Louis Stevenson and Jack London.

But this quintessentially Hawaiian instrument, a symbol of local pride and native culture, actually has roots on an island half a world away. About two centuries ago, a small, four-string, guitar-like instrument called the machete became popular on the Portuguese archipelago of Madeira, strummed by local sugar cane farm workers. As the Portuguese economy sank in the 1870s, and Hawaii (formerly the Sandwich Islands) boomed with sugar plantations and cattle farms, many Madeirans emigrated to meet the demand for labor.

Among the new immigrants to Hawaii were Portuguese woodworkers and musicians who brought their favorite instrument with them. The proto-ukulele’s first local mention was in 1879, when the Hawaiian Gazette noted “a band of Portuguese musicians, … fine performers on their strange instruments which are a kind of cross between a guitar and banjo but which produce very sweet music.”

Portuguese craftsmen soon discovered that wood from the endemic Hawaiian koa tree proved to be ideal for shaping the instruments and producing fine tones. As local production began, Hawaiians adopted the instrument with enthusiasm, their strumming and singing becoming ubiquitous across the islands by the mid 1880s. Some tourists actually complained that they heard it “27 out of 24 hours in the day” according to the Gazette. One version of the instrument was called the taro patch fiddle, but given the players’ fast-moving fingers hopping all over the strings, the instrument soon earned the name ukulele, Hawaiian for “jumping flea.”

Given the players’ fast-moving fingers hopping all over the strings, the instrument soon earned the name ukulele, Hawaiian for “jumping flea.”

As U.S. business interests expanded in Hawaii, and annexation talk began in the late 1880s, the ukulele became a symbol of national identity. According to Jim Tranquada and John King’s The ‘Ukulele: A History, the court of King Kalakaua first used the ukulele in hula performances at his coronation in 1883. His daughter, soon to be Queen Liliuokalani, composed the anthem “Aloha Oe,” still taught to every Hawaiian child. Following the U.S. overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, the “sweet” local songs, unintelligible to most visitors, often were anthems of protest against the new rulers.

As U.S. culture permeated the islands, the “jumping flea” leapt to the mainland. What began with a trickle of popularity with ukulele performances at the Hawaiian booth at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair became a full-fledged craze after Hawaiian ukulele bands played at the 1915 Pan-Pacific Expo in San Francisco. “The country has all of a sudden gone mad over Hawaiian music,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle in 1916.

The instrument took over Broadway in 1916, with the Ziegfeld Follies and Irving Berlin productions featuring hula and ukuleles. It soon jumped into the vaudeville circuit and Tin Pan Alley recordings, including Al Jolson’s hit song “Yaaka Hula Hickey Dula” and others, like “The Honolulu Hicki Boola Boo.” Hawaiians ridiculed such performances as hapa haole style (a derogatory term referring to those who were half-Hawaiian and half-white-foreigner) — a usurpation of Hawaiian culture lacking in understanding or appreciation.

Nonetheless, East and West Coast Americans embraced the fad, learning to play the ukulele, enjoying its low cost, portability, and ease of learning. When U.S. troops sailed to Europe during World War I, the ukuleles came with them, and the returning soldiers spread the instrument’s popularity more widely across the U.S.

It was in the post-war Roaring Twenties that ukuleles reached peak saturation, becoming the top-selling instrument in the country by 1925, with four million sold, most produced by mainland companies like Martin and Gibson. It became a required hipster accessory on college campuses, a must-have for any party.

By the Depression years of the 1930s, ukulele music had become a cliché, used to suggest frivolous old times. The instrument was smashed to bits in movies by Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy, and mocked as “a public menace … a hideous musical instrument” in a P.G. Wodehouse novel. Sales plummeted, and the ukulele was relegated to a historic souvenir.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the ukulele would make a comeback — driven by the availability of cheap plastic models as well as by the popularity of uke-playing radio and TV star Arthur Godfrey. The paired inventions of moldable plastics and television brought ukuleles into living rooms across America. Sales soared once again from an estimated 26,000 in 1948 to 1.7 million in 1951.

But this second ukulele craze came and went as big and fast as a Hawaiian hurricane. By the 1960s, the ukulele was decidedly uncool, every kid wanting to learn guitar instead. Tiny Tim, the late-’60s novelty act, cemented the perception of the ukulele as a silly toy, a plastic throwaway meant for little kids and comedians.

Then, at least in Hawaii, it was back. In the 1970s and ’80s, a resurgence in cultural pride and the success of musicians like Eddie Kamae and the Ka‘au Crater Boys made the instrument cool again. “You didn’t want to be the only kid who couldn’t jam during recess,” Tyler Gilman, owner of The Ukulele Shop in Waikiki, said of growing up then. Roy Sakuma launched his annual Ukulele Festival in Honolulu in 1971 in the hope of repopularizing the instrument. “I thought it would be the first and only one,” he said, “But here we are getting ready for the Festival’s 50th anniversary on July 19th!”

It took a while, but the ukulele once again made a jump to the mainland after Hawaiian singer-songwriter Israel “Brother IZ” Kamakawiwo‘ole’s soulful ukulele rendition of “Over the Rainbow” became a mainstream hit in the 1990s. Something about the sweet sound and incongruous look of a 500-pound man playing a tiny ukulele seemed to resonate.

In 2006, YouTube sparked the popularity of American ukulele virtuoso and composer Jake Shimabukuro when his arrangement of the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” became a viral sensation. The instrument’s continued cross-genre popularity included a top-selling ukulele album by Pearl Jam front man Eddie Vedder in 2011, and recent uke-based hits like Jason Mraz’s “I’m Yours” and Train’s “Hey, Soul Sister.”

After all its ups and downs, is the instrument finally here to stay? Fred Kamaka Jr. of Kamaka Ukuleles says, “The ukulele is just too mainstream now to fade away again.”

“The ukulele is still on the upswing,” says Shimabukuro. “Everywhere I go in the world, people are embracing it.”

Mike Upton, CEO of the top-selling Kala Brand ukuleles, adds: “Our sales just keep increasing. It’s kids, it’s performers, it’s collectors, everyone seems to want one.”

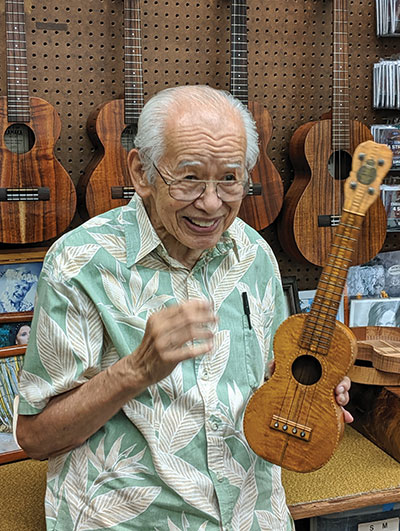

In Hawaii, oversubscribed grade school ukulele clubs are developing the stars of tomorrow. Local artisans continue to make ukuleles on the islands, and stalwart Kamaka is still crafting ukuleles as it has done since the initial wave of popularity in 1915, with a two-month waiting list to get a new instrument. Fred Kamaka Sr., the 95-year-old son of the founder, greeted my recent tour at their Honolulu workshop. Having lived through every boom and bust of the instrument, he’s confident about its future. He plucked the four strings of a 100-year-old display model and said, “There it is, the same sound as my father made. Doesn’t it make you smile?”

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Hawaiian State Archives

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now