For many Americans, the crisis of mass incarceration is a daily encumbrance. These are the children, wives, boyfriends, grandmothers, nephews, and friends of the 2.3 million people who are locked up in the United States. Journalist Sylvia A. Harvey has spent time with family members of incarcerated people — having been a family member of one herself — and her recent book, The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family, tells their stories in intimate detail.

Although many in this country still look at full prisons and see criminals rightly serving their sentence, Harvey maintains, as many others have, that the price we pay for so much incarceration can be tracked through generations of wrecked communities. She writes:

When people are incarcerated, we as a society rarely consider the lives — and the people — left behind. But their former lives don’t simply vanish. For their children, those prisoners remain parents. The collateral effects of mass incarceration cut through the immediate fabric first, then penetrate the entire extended family for generations. The most fragile of those impacted are the children.

If you’ve never met someone affected by America’s prison system, Harvey believes you should read her book. In our interview, she paints a picture of what life can look like when someone you love is behind bars. The costs, financially and emotionally, of the highest incarceration rate in the world are paid heavily by the families of the disproportionately black and poor prison population. Harvey says that this isn’t inevitable, and that the patchwork of policies and programs around the country often point to what works better, if only we can find the political will to act on it.

The Saturday Evening Post: In your book, you write about how you’ve been affected personally by incarceration. Can you talk about that?

Sylvia A. Harvey: Yeah, I experienced parental incarceration from my father for about 27 years in different California prisons. What’s been important for me, having that experience, is being able to utilize that to see what’s happening around the country to 2.3 million families, people who are directly impacted now. My father spent 27 years in prison, and that’s been significantly helpful in thinking about how policies need to change and how families are being impacted.

SEP: How did you find the families whose stories you featured in this book?

Harvey: That was actually a task. What I started to do was to call organizations from each state that was of interest for some reason. So, I picked Mississippi because of what’s happening there in terms of race relations. It is not a progressive state, so to speak. So, to look at incarceration and its impact on families in a conservative state, in a place like that, it meant calling any organizations that worked with families impacted by that. There weren’t very many programs, so it was difficult. So then I called local churches, local organizations. It was literally looking at what kinds of organizations were in place at the grassroots level.

Florida was a little bit easier because they had more organizations that worked with this demographic. I started to go along on some of the visits they had in Florida with the Children of Inmates program, going along on some of those trips and sitting in the visiting room. From doing some of that preliminary reporting, I was able to determine which families were most suitable for the book.

SEP: Could you give a rundown of the three families you covered in The Shadow System?

Harvey: In Miami, I looked at a young man, a young black man, who has a murder conviction. So, what does that mean for a young person in Miami to have this kind of conviction, and what does that mean for his daughter? In Jackson, Mississippi, now we have a family where the father has been incarcerated for 39 years. So, what does it look like to have a life sentence and to have served almost 40 years of that sentence? Being able to look back on how that manifests in his family, his three children who are all black boys. In Louisville, Kentucky, I was focusing on returning citizens, and predominately white women who were impacted by the opioid epidemic, as they returned home. So, looking at issues across the country with different demographics.

SEP: What surprised you about how other people who have been affected by incarceration live and cope with that?

Harvey: I think, the availability of resources. So, in different states you have different resources. That was — I wouldn’t say shocking — but why I decided to write the book in this way, to focus on states that are not represented often, the states we don’t really think about. It was surprising for me to see exactly how incarceration manifests. Like, how you could serve as much time as the man in Mississippi did and be able to look at other states where they’re releasing people.

I was surprised by the difference in legislation, the difference in sentencing, and the difference in resources. In Jackson, there weren’t very many resources, but if you go to Miami, there’s this program where they’re literally taking these children and their families all over the state to visit their parents in prison four times a year. This is a resource that is state-funded, so why doesn’t that exist in other parts of the country? There’s a disparity in resources available, disparity in sentencing, disparity in visitation, depending on where you are in the country.

SEP: How did visitation differ from case to case, and what does that process look like?

Harvey: In the book, my focus is on family visitation. So, family visitation was something that was taking place in Jackson, Mississippi. Family visits in that state were three to five nights, where you could literally go on prison grounds in a small apartment or trailer that’s sort of set up to mimic the idea of being home. That’s the kind of visitation I focused on because it’s obviously the most progressive visitation, and I wanted people to be able to look at that and see what that means. It means these families are able to go and feel like they’re at home again. The mother who has three children and a husband who’s been incarcerated for 39 years is able to continue to build with her partner by having these visits. That’s pretty significant. I think it’s important to be able to look at that and see what that means, what that feels like, and why it no longer exists in some states but still exists in others.

SEP: What does visitation look like in other places where they don’t have those types of programs?

Harvey: It really depends, so in some states you’ll have visitation that is behind the plexiglass, no contact, and in some places you’ll have video visits. A lot of jails are turning to video visits only, which means you’re going to the jail facility but only using video. Some visits allow contact, but it’s limited contact, so you go to the jail or prison and, for the first, maybe 15 seconds, you’re able to greet the person, give them a hug or kiss or whatever, but there’s a limitation on the physical contact you can have. Some facilities will allow you to maybe hold hands but nothing more than that. It really differs from state to state, city to city, jail to prison, it’s a broad spectrum of what can and cannot take place.

SEP: You write about the people in Kentucky who have been affected by the opioid epidemic. Can you talk about how that crisis has been handled differently than drug epidemics of the past?

Harvey: Yeah, I would say that the 1980s war on drugs — all of that legislation — literally ensured that people of color were under attack. From that alone, they were overrepresented in jails and prisons. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was something that really put racial minorities in a chokehold. The thinking of criminality, the idea of looking at it as something people were doing and not something happening to people. We weren’t thinking about it in the context of a health crisis. And now, we’re looking at the opioid epidemic as a health crisis. Like, “how do we fix this? How do we help people?” That was not the narrative when we had the war on drugs during the crack epidemic. It was “let’s lock all of these people up,” and I think that’s been a huge distinction.

SEP: How have companies been profiting off the increase in incarceration?

Harvey: Financial exploitation of families by the prison industry is huge. We see that in phone calls, e-mails, videos, these are all services that we on the outside are able to access quite easily. That is not the reality for people who are incarcerated. They have to pay a really high rate for these things. In Jackson, one of the families paid $6.99 for her video call that was 15 minutes. What does that mean for those families to pay that every time they want to interact with their incarcerated loved one? In some counties, it’s up to 25 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. That exists. It’s a huge industry. The going rate for hundreds of counties is 15 to 18 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. Some of these costly rates are driven up hundreds of millions of dollars by concession fees. We would call them “kickbacks.” The phone companies are paying local and state prison systems in exchange for these exclusive contracts. So, as long as they’re getting this kickback, why give them free or cheap ways to communicate?

And on top of that, we also have commissary. This is like the prison retail market. So, inside these prisons, people still need access to things. If you get a small bar of soap or if you get limited food during lunchtime or dinner, you order extra from the commissary. It’s not always that the commissary is significantly higher, but it’s high when we think about the prisoners who are paying for this. If you make four dollars a day and then you have to pay four dollars for a fungal cream, then that is exorbitant for you. Families spent $1.8 billion on commissary in a year most recently, and that’s a lot of money for families to spend. [Prison Policy Initiative found that American families spent $2.9 billion on commissary and phone calls yearly in 2017.]

I think as long as that is happening, then families will be exploited. We have to think about why it is that we can charge that. We say, to a degree, that “they can’t have cell phones” because “we don’t know what they would do with these cell phones,” but a lot of this is just financial exploitation. Private companies have found a number of ways of making sure it’s profitable. These families want to stay in touch, and if they have to go in debt trying to, that’s what you do.

SEP: Who do you think should be reading your book?

Harvey: I would say, people who are not familiar with the concept of mass incarceration and how it is impacting this country; not only people who already care about incarceration. Everyone who wants to be informed and be good citizens should be reading this book. As humans, we need to be thinking about what our country is doing, in terms of policy, that is impacting specific demographics. We need to be thinking about why it’s impacting black, brown, and poor people at such a high rate, and what that says about how we feel about those people. It needs to be read far beyond the advocates, far beyond the reformists, far beyond the directly impacted, but by those who are not familiar with what is happening but should be. We can’t continue to allow willful ignorance; I think everybody needs to demand that we have an equitable system in this country. Everyone should be reading it, and especially those who aren’t familiar with how morally bankrupt our system is.

It’s easy to give out statistics, like, “hey, 2.3 million people are incarcerated, 555,000 of those people are locked up pre-trial, which means they can’t go home because they don’t have the money,” but if you haven’t had a friend or family member face that, then you don’t understand that. So it’s easy to say that, but what does that mean? What does that look like? If I tell you a story about a young man who faces this and what that means for him, then we’re like “huh, that that’s how that works.” So I think it’s important to use narrative and storytelling to illustrate how policy is impacting people. That way, we’re able to connect to the person and understand the policy behind that.

SEP: Speaking of pre-trial, you write quite a bit about people serving long prison sentences, but we have seen jailing in the short-term increase a lot in this country, especially in rural areas.

Harvey: In Louisville, a lot of the women I interviewed were actually from eastern Kentucky. So, it’s very rural, and there’s not a lot of access to rehabilitation programs or drug or alcohol treatment that goes beyond the seven days, so they were jailed and then released to this program, The Healing Place, that allowed them to have a longer stay to really deal with this drug or alcohol issue. One of the young women in the book served 18 days, and the 18 days she served in jail impacted her heavily because while she was in jail, her children were put into foster care. Once this woman got out of jail, she figured she’d pick up her kids, but you can’t just pick up your kids once they’re in the child welfare system. She spent less than a month in jail, but once she got out she had this huge battle ahead of her, because we’re looking at the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and how it impacts families of people who are incarcerated. So, she was now up against this clock. So they gave her a case plan saying she had to complete a drug and alcohol treatment program, get a job, make visits once a week. But with the treatment program she was in, she couldn’t leave for extended periods of time to make her visits. She was in violation of her case plan because of her treatment program. So there was this conflict between whether the Department of Human Services was considering what it means for this woman and people like her who are in these kinds of programs that have a lot of stipulations and limitations, because you’re supposed to be focusing on your recovery.

So, here’s a woman who — in less than one month — her life was turned upside down because her children were taken away from her. That could accelerate her addiction, and she could lose her house, her car, her job, and then she doesn’t have anything. So, it doesn’t have to be 20 years in prison. You could be in jail for a week and lose your job. A lot of people are living paycheck to paycheck, so there’s really just one step away from their lives falling apart. One step away from no car, one step away from homelessness.

SEP: What have you been seeing in jails and prisons with the recent pandemic? Some outlets have covered the lack of response in these facilities, and the kind of crisis that could create.

Harvey: I saw that in a jail where there were more than 600 cases, they were literally writing on their windows “help us,” like, “we matter too,” crying out to the public that even if they are in there and convicted of a crime, they don’t deserve to die there because the proper precautions haven’t been taken to make sure they’re not at a greater risk to contract this virus. And we’ve seen people contracting and dying from this virus in federal prisons. There was a man who had served 44 years and he was due out this year, and he just died from COVID-19 behind bars. All of the people who work in these facilities do come back to their communities. So if you don’t think that incarcerated persons are important or valuable or that their health should be considered, think about the people who work in these facilities. This is a public health threat. Some local governments are suspending jail times for low-level violations, or reducing arrests for minor offenses. Some places are releasing pre-trial detainees. We are seeing some things happening, but it’s not happening quick enough.

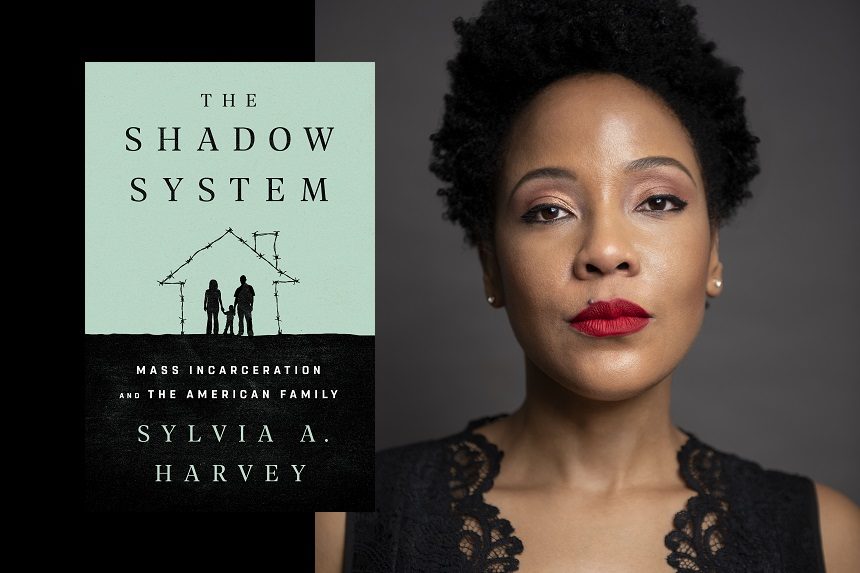

Featured image: Photo by Rayon Richards.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now