It was one of the greatest — and most disturbing — success stories of the 1920s. In just five years, the Ku Klux Klan grew its membership from a few thousand to five million. What had been an organization principally of rural white southerners in the 1860s now included among its members doctors, lawyers, and professors in both northern and southern states. How did they do it? Like any modern organization: they launched a marketing campaign.

The Klan had begun as a fraternal order of former Confederate soldiers who terrorized freed slaves and members of the state governments implementing Reconstruction. But when Reconstruction was dismantled, the Klan melted away.

By 1915, the Klan had just one member: William Joseph Simmons. He was inspired to revive the organization after watching D. W. Griffith’s film, Birth of a Nation, which portrayed Klansmen as heroes.

To Simmons, 1915 seemed right for the Klan’s return. Many southerners were angered by progressive policies that were expanding the federal government and supporting civil rights for minorities. Also, many resented the flood of immigrants and feared foreign cultures would destroy what they considered “traditional American values.”

Simmons felt the country would be receptive to an organization pledged to white nationalism. On Thanksgiving Eve, 1915, atop Stone Mountain near Atlanta, Simmons swore 15 candidates into the revived Klan. After they repeated the oath, he set a large cross on fire. It was a bit of stagecraft dreamed up from Birth of a Nation that had captivated Simmons, and it soon became a Klan tradition.

But something was missing. Recruitment was slow. In five years, Simmons had added only 5,000 members.

Then he met Mary Tyler and Edward Clarke, professional fundraisers who saw potential in the Klan, particularly when Simmons offered them 80 percent of the profits from dues. In June 1920, they became the brains behind the Klan’s national marketing campaign.

The timing for a racist organization was better than it had been five years earlier. There was a new defiance among black Army veterans, now returning to the South from the war. Having served their country, they were unwilling to reprise any subservient role in their communities. Major race riots had already erupted in several cities.

But Clarke and Tyler realized that racism wasn’t enough. Not every part of America was as interested in suppressing black Americans and protecting white power. The Klan couldn’t grow unless it reached a broader audience.

So Clarke and Tyler divided the country in eight regions and sent out 1,000 agents to identify the focus of bigotry and fear in their assigned areas: labor-union organizers and communists in the industrial north, Asians on the west coast, Jews and Catholics almost anywhere.

They began to expand the Klan’s mission, stirring hatred against these groups.

The two also tapped into Americans’ anger at accelerated social change. They wanted to channel the disapproval of the media that mocked tradition, the rebellious attitude of young people, the immodest behavior of women, and, of course, jazz.

Having relatively few adherents in cities, the Klan adopted several attitudes popular in rural areas. They helped enforce Prohibition and they denounced motion pictures.

Almost everywhere they found a public yearning for a golden past, where they remembered an America free of foreign influences. Millions were drawn to the Klan’s policy of “America for Americans” as well as its sometimes violent enforcement of fundamentalist Protestant values.

Many members would never have supported the beatings, tar-and-featherings, murders, and kidnappings committed by other Klansmen. They believed in the Klan was a patriotic, God-fearing organization that revered traditional values. To them, it was simply a fraternal organization, a good place to enjoy white privilege, and maybe do some business networking.

Tyler realized that American women were another promising market. “The Klan stands for the things women hold most dear,” she told the New York Times in 1921. She developed a women’s Klan that eventually claimed 500,000 members, who hosted picnics and attended cross burnings.

They launched a modern media campaign for Simmons, lining up interviews with reporters. Suddenly the Klan’s message was reaching whole new parts of the country. Within a few months, membership had grown 2,000 percent.

Meanwhile their agents were recruiting members in every part of the country. About half of every $10 initiation fee they collected was forwarded to the national office in Atlanta, most of it flowing into the pockets of Clarke and Tyler.

In addition, they were getting a kickback on the sale of official white robes, charging $6.50 for robes that had cost them $3.28. Sensing even greater profits, they began churning out various Klan publications for members. As another sideline, they managed real estate on Klan-owned properties. Within a year, Clarke and Tyler had taken in over a million dollars.

It had been an illegal, covert organization in the Reconstruction era. But in 1925, over 50,000 Klansmen marched boldly through Washington D.C. And, contrary to tradition, not a single one wore a mask.

Not only had the Klan gained social acceptance, it held political power. Klan-backed candidates held office in city and state governments across America, where they protected the Klan’s interests. In Indiana, Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson could even claim, with good reason, “I am the law.”

The Klan might have seemed unstoppable, but the end came soon afterward as it was rocked by several scandals. In addition, the fallout from several investigations was bringing to light the true work of the Klan.

The New York World’s investigation revealed that, in 1921, the Klan was responsible for four murders, a mutilation, 41 floggings, 27 tar-and-featherings, five kidnappings, and 43 threats and warnings to leave town. Civic groups started posting the Klan’s membership lists publicly, and the NAACP led a successful public education campaign about the abuses of the Klan.

One of the scandals took down Tyler. She and Clarke were planning to oust Simmons and take over the Klan’s leadership when they were arrested in a “house of ill repute.” Police discovered them conducting an affair despite being married to others — while in possession of bootleg alcohol. Klan members were outraged, especially when they discovered Tyler, a woman, had been the force behind the Klan’s rapid growth.

She was accused of embezzlement and forced out of the Klan in 1922.

That same year, the FBI was requested to investigate the Klan control of northern Louisiana. The complaint said members had already tortured and killed two men who had opposed the organization. The FBI focused its efforts on Clarke, who had been able to remain an officer in the Klan and was now taking $8 out of every $10 initiation fee.

Unable to convict Clarke on any existing law, he was charged with violating the Mann Act when he drove his mistress across a state line. He, too, was forced from the Klan and moved out of the country to avoid prosecution.

The Klan’s membership started declining rapidly, from its peak of five million members in 1925 to 30,000 in 1930. It reached a low of 3,000 in 2015. Recently, Klan membership has started to pick back up again. There’s been no official word on who is handling their marketing.

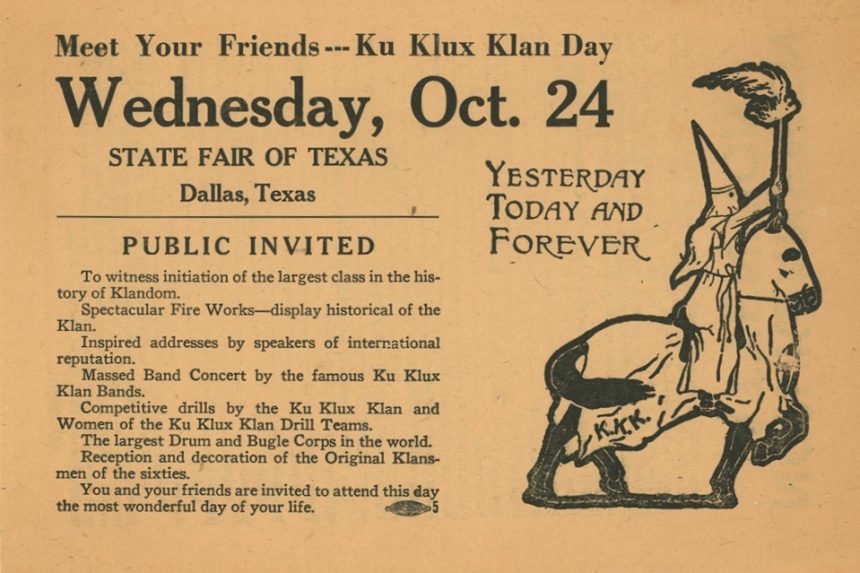

Featured image: A flyer advertising a Klan event at the Texas State Fair, 1923 (The Portal to Texas History, the University of North Texas)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The contempt the American Southerners had and still have for the Union is always surprising to me, in my liberal enclave. I was raised with an entirely different set of values and principals. I sure hope this isn’t a turning point in deciding the direction the country chooses to move in.

But hey, maybe some people’s pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness entails not seeing non-white people. Clearly my tolerance should extend to those who cannot tolerate their existence.

It’s surprising how many people fell for the lines in the marketing back then, and even now. Likely, a problem with education. Too many people aren’t taught how to think critically without just criticizing.

Just like in the 1920’s the 2020’s appear to be filling with people that make declarations of how other people think and what they want. Statements based on what they ‘think’ others have said and might only later find out it wasn’t true.

The Klan’s tactics seem to being repeated by Donald Trump and his followers. They want “nationalism” and mostly white power along with their disdain for immigrants who are not white. Very scarry!!!

This article is pretty shocking, and yet not that surprising at the same time. It’s really horrifying, and shows a frightening side of the ’20s not revealed very often. From a marketing, recruiting standpoint (I suppose) you have to admire them for knowing what to do, and when to do it.

I’m sure many legitimate businesses have taken pages out of their playbook for good reasons. Between this pandemic (and new cases spiking), the daily race relations horrors just in this past week alone, the opening and re-closings of business, the KKK is likely sizing it all up as to what to do, and which tactics to use now to go big once again.