Each year when Father’s Day rolls around, I think of the late Erma Bombeck.

While she mined family life for years in her syndicated column and best-selling books, on June 21, 1981 — Father’s Day that year — she plumbed memories of her father for one of the most unforgettable columns ever to appear on the printed page.

If you think that’s a bit much, it was so good it was reprinted by Reader’s Digest. And in 1989, when the editor of Reader’s Digest undertook a special project to determine the best articles that had ever been published in the magazine — he went back and read through all 67 years of issues — Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column was one of them.

If you wonder why, consider her opening.

When I was a little kid, a father was like the light in the refrigerator. Every house had one, but no one really knew what either of them did once the door was shut.

For years I used Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column as an example of the power of the telling detail when I taught feature writing at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina (now the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media).

He opened the jar of pickles when no one else at home could.

He was the only one in the house who wasn’t afraid to go into the basement by himself.

A bit later —

It was understood that whenever it rained, he got the car and brought it around to the door.

When anyone was sick, he went out to get the prescription filled.

And —

He took a lot of pictures, but was never in them.

When we discussed it in class, students — year after year after year — would say, “My father didn’t do that. He cut the wood for the fireplace.” Or, “My Dad didn’t do that. He put up a backboard and hoop on the garage so I could shoot basketballs.” Or, “Daddy didn’t do any of those things. But when he made the popcorn, he put lots of butter on it.”

That is what fathers do.

That with time we come to appreciate, and recognize on Father’s Day.

While it’s been celebrated by Catholic institutions since the Middle Ages (March 19, St. Joseph’s Day), and President Woodrow Wilson tried to establish a national Father’s Day in 1913, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the idea gained traction, due in part to growing support from manufacturers and merchants who would benefit from the sale of items for fathers.

Still, many Americans continued to resist, viewing Father’s Day as nothing more than an attempt to replicate Mother’s Day. (I remember asking when Children’s Day was and being told, “Every day is Children’s Day.”)

The resistance would weaken with the years, but it was not until 1966 that the first presidential proclamation designating the third Sunday in June as Father’s Day was signed — by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1972 President Richard Nixon signed the law making it a permanent national holiday.

With my first Father’s Day gifts, I learned — with a little help from Christmas — never to buy my father ties. I might be young and still growing, but I picked up quickly on the fact that, however nice he was, however much he loved me, he’d rather pick out his own.

Like Erma Bombeck, it’s when I look back that I realize how much he did.

My father was the one who set and emptied the mouse traps. He stood alongside the Christmas tree in the lot, turning it slowly as my mother and I stood back, checking the symmetry, to be sure it was perfect. He spent his summer vacations painting the kitchen (or bedroom or bathroom), undoubtedly happy to get back to work.

He wasn’t a gourmet cook, or even your everyday cook, but on Sunday morning he went into the kitchen and made pancakes. He would let the batter spread out on the griddle into a near-perfect circle, then add a bit at the top of one — mine — like the stem on an apple. A “handle,” he said. Just for me.

As most fathers do, I suspect, he deferred to my mother on most of the things a parent can rule/guide/steer/suggest — especially, mothers with girls. But he insisted on two things.

1. I must know how to reconcile a bank statement. I do. But I don’t like to do it.

I like to think he would be as happy as I am that technology, i.e., my online bank account, has eased that almost into oblivion.

2. I must put my own worms on the fish hook. I did. But I’d never enter a fishing contest, however shiny the first prize trophy.

Did I mention he cleaned the fish?

My father did not run alongside my bike “for at least a thousand miles until I got the hang of it,” as Erma Bombeck’s father had, but we faced the same challenges of forward motion when he taught me how to drive. The most vivid and lasting memory that came out of that was my appreciation — and his, I daresay — for the invention of the automatic transmission, which would bear many names, the one I remember being Hydramatic.

I consider it up there with the discovery of fire and invention of the wheel.

Alas, it was still in the laboratory the afternoon Daddy took me out to a gravel country road, more specifically a hill with a considerable incline, and introduced me to the finer points of coordinating the clutch, the accelerator, and the brake.

It is an acquired skill.

Bob Newhart had a classic comedy routine on this trying form of human endeavor known as driver education that I heard on the radio one afternoon while driving on the Merritt Parkway in Westport, Conn., and laughed so hard I almost had to pull over. In that case, it was a paid instructor suffering the torment of a driver still in training.

My father did it for love.

And I love him for it.

And all the other things he did that time has turned to gold.

Little things.

Things that have survived the years, the day’s breaking news, the aches and pains of aging, to not only mean a lot. To mean everything.

Like the time — it was before Hallmark cards became the staple of Valentine’s Day — that I worked on a package of pieces for Valentines that you assembled yourself. My grandmother had bought the package for me, and this particular afternoon I was at her house working on the Valentines to present to my loved ones.

You had to paste the lace-y white sheets over the Valentines. They had little paper feet you attached appropriately. Although the paste that I used was homemade — flour and water in the proper proportions, which my grandmother knew — it worked on the little paper feet. They stuck nicely.

And that might have been the end of it except that when I finished I decided to make chocolate pudding for dessert that night. I was only seven, but I managed to reach the cookbook. I mixed the ingredients, found a pan into which I poured the pudding-to-be, and set the pan on the stove. A white enamel stove set up on cabriolet legs, the burners were chest high for me. The handles were on the front, though, so I could reach them. They were also white ceramic, and I turned the one in front of me. It was a gas stove, with flames that licked at the sauce pan.

I stirred. And stirred. And stirred.

When it didn’t thicken, I remembered the flour and water my grandmother had mixed for the paste for my Valentines. And creating a family story for years to come, put the paste in the pudding.

By the time we went to eat it, the pudding still looked like the chocolate pudding I had poured into the pretty glass dessert dishes. But it had taken on certain qualities and characteristics we associate with concrete. I couldn’t get my spoon into it, nor could most of the adults at the table. But Daddy chipped away … and chipped away … and chipped away until he had a spoonful. You could almost hear it clink as it went down.

He even managed a smile as he looked over at me and said, “It’s very good, honey.”

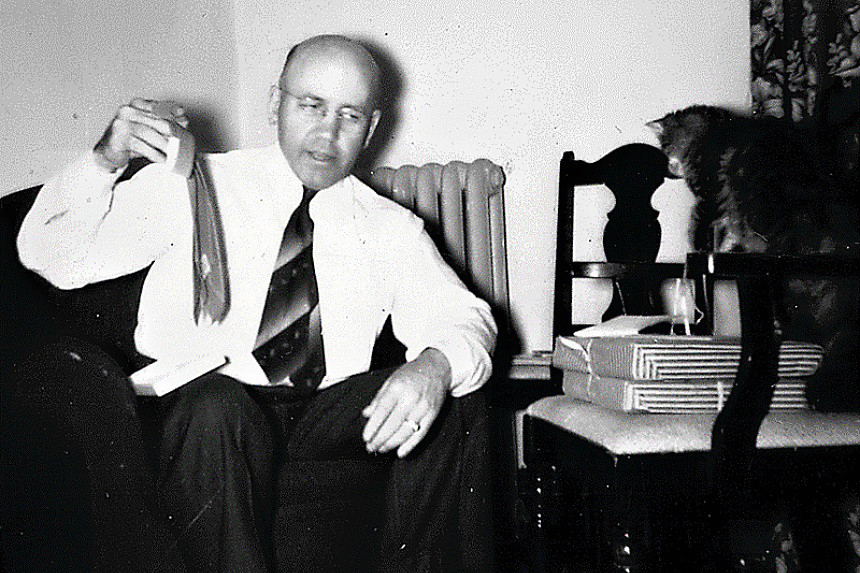

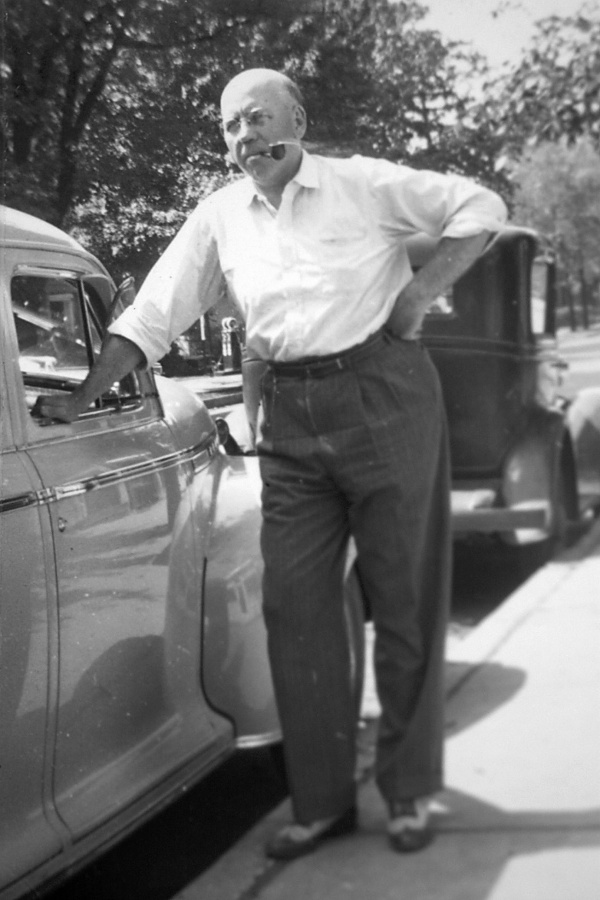

All photographs courtesy of Val Lauder

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Great article. It sounds like you had a great family. I’ve done some of the things you and Erma Bombeck mentioned. The article reminded me times when I went to some rough looking places and into groups of strangers to get back my daughter’s items that their kids had taken (not intentionally). At the time it was autopilot. Afterwards I thought I was lucky I didn’t get beat up.

I’ve done other stuff that she will hopefully recall fondly – a couple of fire events, armed guarding her from some sketchy folks in a pitch black parking lot on the Blue Ridge Parkway, concerts, sporting events, etc. Being a dad is the best thing that can happen to a person.

What a nice tribute you wrote here for your dad Val, and fathers in general. They just DON’T get the same respect as mothers do they? To put it another way, mothers will get a one pound box of See’s Candies, and fathers will get their chocolate cigar.

Let us thank Presidents’ Johnson and Nixon for giving dad his day, even though he doesn’t get his due. Truth be told I went out a lot more for my mom (one lb. box of the See’s dark chocolates + a special Hallmark card) and a Hallmark card for my dad. I know parents aren’t supposed to have a favorite child, but how can that be, really, when the child has a favorite parent? My mom preferred me over my sister, and my dad my sister over me. There was often friction between between mother/daughter and father/son. Which child was preferred by his grandparents for being more loving, fun, helpful and entertaining?

I love how your dad taught you how to drive, Val. I was trying to figure out what car your dad was getting into in the picture. When you mentioned Hydramatic I figured it was likely a 1940 or ’41 Oldsmobile. GM first introduced THE first automatic transmission on the ’40 Olds (their experimental division) instead of Cadillac so if there were any problems it wouldn’t tarnish Caddy’s name.

In a cool coincidence, I learned how to drive on a ’74 Olds Cutlass Supreme with the half-padded rear roof and opera windows. This was at Van Nuys High School, and the cars were provided by the LAUSD, can you believe it? Such extravagance of a very bygone era. A year later I got a summer job at a small auto parts store where you needed to know how to drive a stick shift. My mom rented a stick Pinto from Avis and showed me how; she learned how to drive on one. I wound up stripping the gears though in the Sunkist building parking lot in Sherman Oaks we were practicing in.

Normally honest to a fault, she said “I think I can get it back to Avis; don’t say anything!” She did, and told the guy “something was wrong with it” and “thank God nothing happened” taking a Kleenex out to wipe her eyes. He said not to worry and gave her the money back. She took it, said thank you, and we walked to her car to go home. “Don’t ever put me in that position again, and not a word to your father about this!”

In grade school we used flour and water for paste for different arts & crafts projects. I still love making things to this day, but use the glue stick instead. I liked how you talked about the pudding. It wasn’t much fun cooking chocolate pudding before 1971 or ’72 when Soft Swirl (mousse) pudding by Jell-O came out. Just add milk and the electric beaters did the rest, just like Florence Henderson said in the commercials. Too bad its not around anymore.