On a recent episode of the podcast RN-Mentor, Robin Cogan gave a less-conspicuous perspective on the current push for schools across the country to return to in-person learning: that of a school nurse. “When I look at opening schools,” she said, “and I’ve been very entrenched in it both at the state level and at the local level — it feels to me like we’re doing the biggest social experiment ever without an IRB [institutional review board] … our hypothesis: we are going to have kids and staff that are sick and, God forbid, die.”

Cogan, a Nationally Certified School Nurse from New Jersey, writes the blog Relentless School Nurse, where she’s been sharing useful information as well as stories from school nurses around the country. One has been tasked with providing their own personal protective equipment. Another spoke out against her school’s reopening plan in Georgia and resigned from her position. Cogan’s recent posts have revolved around a central theme: “It Has Taken a Pandemic to Understand the Importance of School Nurses.”

Around a century ago, school districts around the country were just coming to realize the value of adding a nurse to their ranks. In newspapers from Sacramento to Bloomington, Illinois to Washington, D.C., stories applauded school boards for often-unanimous decisions to budget for school nurses.

In 1918, The Charlotte News reproduced an entire paper read by a Miss Stella Tylski at a P.T.A. meeting: “There can be little doubt, that as the work of the nurse becomes better understood, there will be a greater demand all over the world for her services in the schools, for wherever she has made her entry, her value has been recognized.”

At some point in the last 100 years, however, school nurses fell off the list of public school priorities. In recent decades, many school districts have been eliminating qualified school nurse positions. According to a 2017 study from the National Association of School Nurses, less than 40 percent of schools employ a full-time nurse. In the western U.S., it’s only 9.6 percent. Twenty-five percent of American schools don’t even have part-time nurses.

As health considerations have taken center stage in conversations around education, it’s difficult to imagine a responsible plan for returning to school during a deadly pandemic that doesn’t include an on-site medical professional. Yet, for many of the country’s strapped schools, that may seem to be the only option.

Since its inception, school nursing has been predicated on public health.

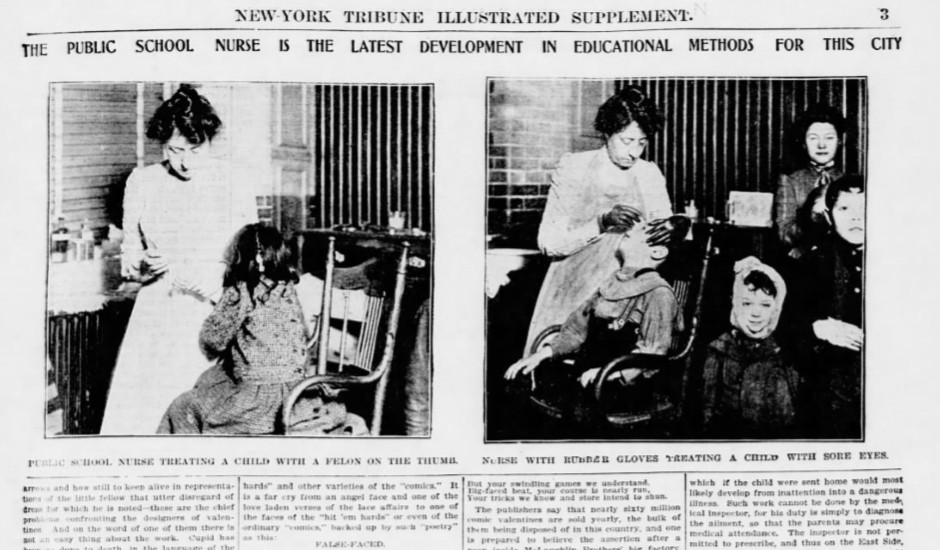

School nursing in the U.S. began as a sort of experiment. At the turn of the century, when cities were becoming crowded with unsanitary slums that beckoned reform, public schools faced attendance problems stemming from influenza, tuberculosis, and skin conditions like eczema and scabies.

Although the New York Board of Health performed routine medical inspections of the city’s schools — and sent home children with troubling symptoms — there wasn’t a system in place to ensure students would recover properly. In 1902, The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by nurse Lillian Wald, pioneered a program to place one nurse in four city schools — with around 10,000 students total — for one month.

The nurse was Lina Rogers, and her undertaking was a significant one. She was to perform her nursing duties at each school with makeshift facilities. At one school, she had only a janitorial closet as an office and an old highchair and radiator as examining furniture. At another, she treated students on the playground. “When children found out that they could have treatment daily and remain in school,” she wrote, “‘sore spots’ seemed to crop up over night.” Perhaps most importantly, Rogers made visits to students’ homes to discuss their ailments and treatment with their parents. She found it difficult, but necessary, to demonstrate medical care and explain the importance of hygiene in preventing illness.

At the end of the Henry Street Settlement’s month-long experiment, Rogers was appointed to lead a team of school nurses in the city. The month before she started in schools, the city saw more than 10,000 absences in a month. One year later, the number of absences for the month was 1,101.

Rogers became a chief advocate for school nursing, and cities across the country noted the Henry Street Settlement’s success. In 1908, The Spokane Press, among many others, applauded the New York school nurses for improving their city’s school attendance and “converting the truant into a studious pupil.”

Rogers wrote a textbook in 1917 detailing her work and giving guidance to the nation’s women who were setting out on this new occupation. She found the presence of health professionals in schools to be a vital aspect of public education’s mission to prepare American children for happy and healthy lives, but she recognized the tall order of staking the health of a community on one position. As she visited students’ homes, she found that things other than illness were keeping them from school, such as babysitting, housework, street crime, and neglect. “So the field of vision of the school nurse rapidly widened,” she wrote. “It was easy to see that if the school children were to be given even a fair opportunity of preparation for life’s work and duties, many things in the social life of the homes had to be improved. All the social problems of humanity, problems as old as the world, face the school nurse at the threshold of her work.”

Throughout the postwar years and the Great Society programs of the 1960s, school health programs were expanded to address drug abuse, students with disabilities, and mental health, among other public health inequities. School nurses became iconic fixtures of American schools, tasked with identifying and treating rising chronic illnesses.

But after the recession of 2008, school funding took a hit. Most states cut funding to education, and much of those losses have yet to be fully recovered. Since school nursing programs rely on school budgets — and few states mandate them — they’ve been quietly eliminated, consolidated, or replaced by untrained employees for years. Less than one-third of private schools employ any kind of school nurse at all.

American school nurses still find themselves advocating for public health amid dire circumstances. Most of them are paid less than 51,000 dollars per year, and the prospects of career mobility in the field are stark. A University of Pennsylvania study found that 46 percent of school nurses were dissatisfied with their opportunities for advancement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, nurses could be among the most important figures at any school.

In a phone call, the president of the National Association of School Nurses, Laurie Combe, mentioned that the first swine flu outbreak was discovered by a school nurse in 2009: Mary Pappas of Queens, New York. “We have expertise in collaborating with health departments to identify, record, and manage communicable diseases in schools,” she said. “We’re the public health practitioners closest to communities on a daily basis.”

According to Combe, nurses are a vital position in any school. She says they have, in many cases, already been working with schools on emergency operations planning. Throughout this pandemic, school nurses have informed their schools on the safe dissemination of food — to families who rely on free and reduced lunches — and technology and educational materials. They’ve continued to make sure students have access to their health providers and medications, as well.

“When schools don’t have the public health and infection control expertise of school nurses, they’re at risk of mismanaging the proper procedures. They risk mixing well children with those who might be symptomatic of COVID-19,” Combe says. “We know that when school teachers have to direct their time to managing health conditions, there is a loss of instructional time, principals lose administrative time. If students are unnecessarily dismissed, parents may lose wages. There is a cross-sector loss of time and money when there is not a school nurse present.”

Combe says the precautions that schools need to put in place in order to reopen during the pandemic are costly, like facility improvement, personnel, and PPE. The NASN is calling on the federal government to direct 208 billion dollars to support schools’ needs. “If schools are essential to reopen the economy,” she says, “then schools need the same financial support as businesses.”

The question of when it is safe for schools to reopen has different answers for different parts of the country, since schools are experiencing the burden of the virus at varying degrees. Cogan writes, “The bare minimum that we need to safely reopen schools is a stable, low rate of COVID-19 in the community [about 5 percent]; funding for and availability of basic public health precautions … and access to testing for students and school staff.”

In the midst of the most drastic public health crisis of our time, the forgotten heroes of our schools may prove to be an imperative component to our national recovery. If it did “take a pandemic to understand the importance of school nurses,” then perhaps that national lesson will endure this time around.

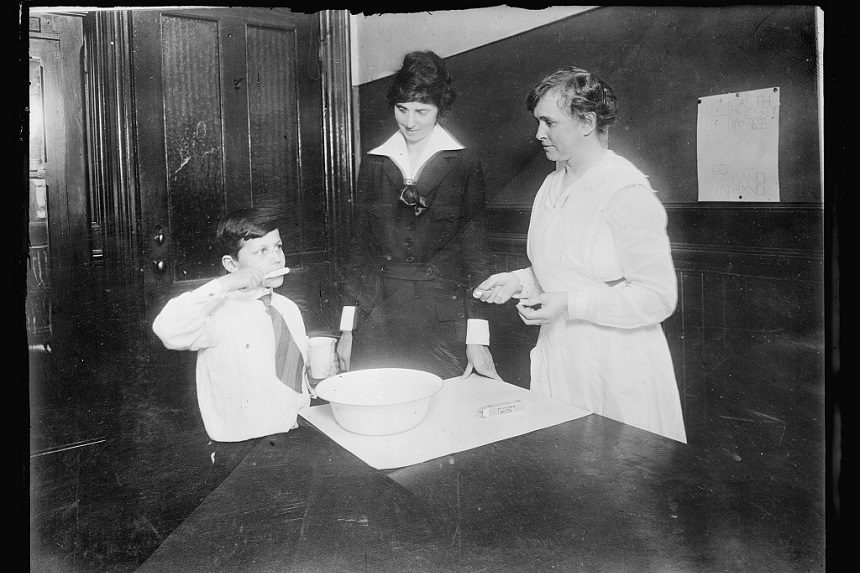

Featured image: American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress), July 1921

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

School nurses for some time have been major front line public health workers. It’s a shame that so many schools have chosen to eliminate them from their staff. Both students and faculty pay the health consequences, and the school loses state money in many cases through worse attendance caused by sickness and mental depression.

My appreciation of school nurses was elevated when I had the opportunity to be a keynoter for the annual meeting of the National Association of School Nurses some 40 years ago. I was a policy analyst in U.S. Dept of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) at the time; the department asked me to represent them at the NASN meeting since I had a background in health education and served in the Peace Corps, making me unique among the department’s educational policy folks. In any event, early on in my remarks I sarcastically opined that Congress should rename the department “D.E.W.” – Disease, Education, and Welfare – since we have nothing to do with health. Some 800 nurses gave me a standing ovation, despite being only 5 minutes into my remarks. They had been singing from the same song sheet for years and needed to have someone from government validate their impression that people in power had no idea what they were doing and advocating to make our children healthy and safe.

Certainly, Covid-19 should wake up school and state authorities to the phenomenal contribution school nurses can make with the proper orientation, training and supervision. The organization called Community Schools has known this for decades. As a society, we should embrace the basic tenet that the integration of health, education and welfare should be pillars of any school that one would want for their children.

A badly needed look at an overlooked and underappreciated profession. The school nurse has traditionally been an essential and front line healthcare worker. I’d like to think that the current, disastrous pandemic would have the same affect in restoring the beleaguered school nurses to her (or his) place of former prominence.

In the U.S. though, lessons are only temporarily learned (if at all) and it’s back to square one. Maybe if money were prioritized in the right way, that might help. It all gets to be very discouraging after a certain point. This weekend on the national news there were the parents dropping off their sons and daughters to college, just like any other year.

I’m watching in disbelief as they tell the reporters the schools have taken every precaution, so our kids will be fine. The kids are alright. Really? Just how brain-dead are they? Plenty of schools said that 2 weeks ago, and now they’re closed with HUGE numbers of students and teachers now testing positive. I knew that’s exactly what would happen, and has. If they can’t learn online, then sit the ’20-’21 school year out. Beats the alternative!

Watch all of the universities that will have to be shut down indefinitely even before Labor Day. If they’re dumb enough to be in school now, they deserve whatever happens. What’s really tragic are the essential healthcare workers, doctors and nurses they’ll be killing from getting infected unnecessarily. This isn’t even including all the people not wearing the mask, going to social gatherings, not to mention all of the sick “parties” to see who can catch Covid-19.

The ‘Land of the Ozarks’ mentality of throwing caution to the wind is nationwide, not just Missouri. With fall, then winter coming, can you imagine the numbers looming? Lots of well known, favorite restaurants, stores and more will be gone for good because of personal thoughtlessness and selfishness prolonging the situation instead of the common good. Oh, and blaming the President is no excuse either for poor judgement regarding personal behavior putting others at risk.